Sloped armour

Sloped armour is armour that is oriented neither vertically nor horizontally. Such angled armour is typically mounted on tanks and other armoured fighting vehicles (AFVs), as well as naval vessels such as battleships and cruisers. Sloping an armour plate makes it more difficult to penetrate by anti-tank weapons, such as armour-piercing shells (kinetic energy penetrators) and rockets, if they follow a more or less horizontal trajectory to their target, as is often the case. The improved protection is caused by three main effects.

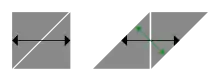

Firstly, a projectile hitting a plate at an angle other than 90° has to move through a greater thickness of armour, compared to hitting the same plate at a right-angle. In the latter case only the plate thickness (the normal to the surface of the armour) must be pierced. Increasing the armour slope improves, for a given plate thickness, the level of protection at the point of impact by increasing the thickness measured in the horizontal plane, the angle of attack of the projectile. The protection of an area, instead of just a single point, is indicated by the average horizontal thickness, which is identical to the area density (in this case relative to the horizontal): the relative armour mass used to protect that area.

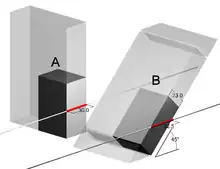

If the horizontal thickness is increased by increasing the slope while keeping the plate thickness constant, a longer and thus heavier armour plate is required to protect a certain area. This improvement in protection is simply equivalent to the increase of areal density and thus mass, and can offer no weight benefit. Therefore, in armoured vehicle design the two other main effects of sloping have been the motive to apply sloped armour.

One of these is the more efficient envelopment of a certain vehicle volume by armour. In general, more rounded shapes have a smaller surface area relative to their volume. In an armoured vehicle that surface must be covered by heavy armour, so a more efficient shape leads to either a substantial weight reduction or a thicker armour for the same weight. Sloping the armour leads to a better approximation of the ideal rounded shape.

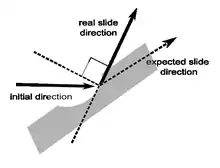

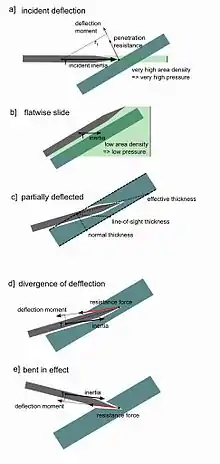

The final effect is that of deflection, deforming and ricochet of a projectile. When it hits a plate under a steep angle, its path might be curved, causing it to move through more armour – or it might bounce off entirely. Also it can be bent, reducing its penetration. Shaped charge warheads may fail to penetrate or even detonate when striking armour at a highly oblique angle. However, these desired effects are critically dependent on the precise armour materials used in relation to the characteristics of the projectile hitting it: sloping might even lead to better penetration.

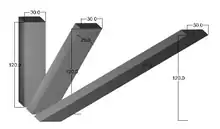

The sharpest angles are usually designed on the frontal glacis plate, because it is the hull direction most likely to be hit while facing an attack, and also because there is more room to slope in the longitudinal direction of the vehicle.

The principle of sloped armour

The cause for the increased protection of a certain point at a given normal thickness is the increased line-of-sight (LOS) thickness of the armour, which is the thickness along the horizontal plane, along a line describing the oncoming projectile's general direction of travel. For a given thickness of armour plate, a projectile must travel through a greater thickness of armour to penetrate into the vehicle when it is sloped.

The mere fact that the LOS-thickness increases by angling the plate is not however the motive for applying sloped armour in armoured vehicle design. The reason for this is that this increase offers no weight benefit. To maintain a given mass of a vehicle, the area density would have to remain equal and this implies that the LOS-thickness would also have to remain constant while the slope increases, which again implies that the normal thickness decreases. In other words: to avoid increasing the weight of the vehicle, plates have to get proportionally thinner while their slope increases, a process equivalent to shearing the mass.

Sloped armour provides increased protection for armoured fighting vehicles through two primary mechanisms. The most important is based on the fact that to attain a certain protection level a certain volume has to be enclosed by a certain mass of armour and that sloping may reduce the surface to volume ratio and thus allow for either a lesser relative mass for a given volume or more protection for a given weight. If attack were equally likely from all directions, the ideal form would be a sphere; because horizontal attack is in fact to be expected the ideal becomes an oblate spheroid. Angling flat plates or curving cast armour allows designers to approach these ideals. For practical reasons this mechanism is most often applied on the front of the vehicle, where there is sufficient room to slope and much of the armour is concentrated, on the assumption that unidirectional frontal attack is the most likely. A simple wedge, such as can be seen in the hull design of the M1 Abrams, is already a good approximation that is often applied.

The second mechanism is that shots hitting sloped armour are more likely to be deflected, ricochet or shatter on impact. Modern weapon and armour technology has significantly reduced this second benefit which initially was the main motive sloped armour was incorporated into vehicle design in the Second World War.

The cosine rule

Even though the increased protection to a point, provided by angling a certain armour plate with a given normal thickness causing an increased line-of-sight (LOS) thickness, is of no consideration in armour vehicle design, it is of great importance when determining the level of protection of a designed vehicle. The LOS-thickness for a vehicle in a horizontal position can be calculated by a simple formula, applying the cosine rule: it is equal to the armour's normal thickness divided by the cosine of the armour's inclination from perpendicularity to the projectile's travel (assumed to be in the horizontal plane) or:

where

- : Line of sight thickness

- : Normal thickness

- : Angle of the sloped armour plate from the vertical

For example, armour sloped sixty degrees back from the vertical presents to a projectile travelling horizontally a line-of-sight thickness twice the armour's normal thickness, as the cosine of 60° is ½. When armour thickness or rolled homogeneous armour equivalency (RHAe) values for AFVs are provided without the slope of the armour, the figure provided generally takes into account this effect of the slope, while when the value is in the format of "x units at y degrees", the effects of the slope are not taken into account.

Deflection

Sloping armour can increase protection by a mechanism such as shattering of a brittle kinetic energy penetrator (KEP) or a deflection of that penetrator away from the surface normal, even though the area density remains constant. These effects are strongest when the projectile has a low absolute weight and is short relative to its width. Armour piercing shells of World War II, certainly those of the early years, had these qualities and sloped armour was therefore rather efficient in that period. In the sixties however long-rod penetrators, such as armour-piercing fin-stabilized discarding sabot rounds, were introduced, projectiles that are both very elongated and very dense in mass. Hitting a sloped thick homogeneous plates such a long-rod penetrator will, after initial penetration into the armour's LOS thickness, bend toward the armour's normal thickness and take a path with a length between the armour's LOS and normal thicknesses. Also the deformed penetrator tends to act as a projectile of a very large diameter and this stretches out the remaining armour, causing it to fail more easily. If these latter effects occur strongly – for modern penetrators this is typically the case for a slope between 55° and 65° – better protection would be provided by vertically mounted armour of the same area density. Another development decreasing the importance of the principle of sloped armour has been the introduction of ceramic armour in the seventies. At any given area density, ceramic armour is also best when mounted more vertically, as maintaining the same area density requires the armour be thinned as it is sloped and the ceramic fractures earlier because of its reduced normal thickness.[1]

Sloped armour can also cause projectiles to ricochet, but this phenomenon is much more complicated and as yet not fully predictable. High rod density, impact velocity, and length-to-diameter ratio are factors that contribute to a high critical ricochet angle (the angle at which ricochet is expected to onset) for a long rod projectile,[2] but different formulae may predict different critical ricochet angles for the same situation.

Basic physical principles of deflection

The behaviour of a real world projectile, and the armour plate it hits, depends on many effects and mechanisms, involving their material structure and continuum mechanics which are very difficult to predict. Using only a few basic principles will therefore not result in a model that is a good description of the full range of possible outcomes. However, in many conditions most of these factors have only a negligible effect while a few of them dominate the equation. Therefore, a very simplified model can be created providing a general idea and understanding of the basic physical principles behind these aspects of sloped armour design.

If the projectile travels very fast, and thus is in a state of hypervelocity, the strength of the armour material becomes negligible, because the energy of impact causes both projectile and armour to melt and behave like fluids, and only its area density is an important factor. In this limiting case, after the hit, the projectile continues to penetrate until it has stopped transferring its momentum to the target matter. In this ideal case, only momentum, area cross section, density and LOS-thickness are relevant. The situation of the penetrating metal jet caused by the explosion of the shaped charge of high-explosive anti-tank (HEAT) ammunition, forms a good approximation of this ideal. Therefore, if the angle is not too extreme, and the projectile is very dense and fast, sloping has little effect and no relevant deflection occurs.

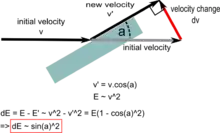

On the other extreme, the more light and slow a projectile is, the more relevant sloping becomes. Typical World War II Armour-Piercing shells were bullet-shaped and had a much lower velocity than a shaped charge jet. An impact would not result in a complete melting of projectile and armour. In this condition the strength of the armour material becomes a relevant factor. If the projectile would be very light and slow, the strength of the armour might even cause the hit to result in just an elastic deformation, the projectile being defeated without damage to the target. Sloping will mean the projectile will have to attain a higher velocity to defeat the armour, because on impact on a sloped armour not all kinetic energy is transferred to the target, the ratio depending on the slope angle. The projectile in a process of elastic collision deflects at an angle of 2 (where denotes the angle between the armour plate surface and the projectile's initial direction), however the change of direction could be virtually divided into a deceleration part, when the projectile is halted when moving in a direction perpendicular to the plate (and will move along the plate after having been deflected at an angle of about ), and a process of elastic acceleration, when the projectile accelerates out of the plate (velocity along the plate is considered as invariant because of negligible friction). Thus the maximum energy accumulated by the plate can be calculated from the deceleration phase of the collision event.

Under the assumption that only elastic deformation occurs and that a target is solid, while disregarding friction, it is easy to calculate the proportion of energy absorbed by a target if it is hit by a projectile, which, if also disregarding more complex deflection effects, after impact bounces off (elastic case) or slides along (idealised inelastic case) the armour plate.

In this very simple model the portion of the energy projected to the target depends on the angle of slope:

where

- : Energy transferred to the target

- : Incident kinetic energy of projectile

- : Angle of the sloped armour plate from the projectile's initial direction

However, in practice the AP-shells were powerful enough that the forces involved reach the plastic deformation limit and the elasticity of the plate could accumulate only a small part of the energy. In that case the armour plate would yield and much of the energy and force be spent by the deformation. As such this means that approximately half the deflection can be assumed (just rather than 2) and the projectile will groove into the plate before it slides along, rather than bounce off. Plasticity surface friction is also very low in comparison to the plastic deformation energy and can be neglected. This implies that the formula above is principally valid also for the plastic deformation case, but because of the gauge grooved into the plate a larger surface angle should be taken into account.

Not only would this imply that the energy transferred to the target would thus be used to damage it; it would also mean that this energy would be higher because the effective angle in the formula is now higher than the angle of the armour slope. The value of the appropriate real ' which should be substituted cannot be derived from this simple principle and can only be determined by a more sophisticated model or simulation.

On the other hand, that very same deformation will also cause, in combination with the armour plate slope, an effect that diminishes armour penetration. Though the deflection is under conditions of plastic deformation smaller, it will nevertheless change the course of the grooving projectile which again will result in an increase of the angle between the new armour surface and the projectile's initial direction. Thus the projectile has to work itself through more armour and, though in absolute terms thereby more energy could be absorbed by the target, it is more easily defeated, the process ideally ending in a complete ricochet.

Historical application

One of the earliest documented instances of the concept of sloped armour is in the drawing of Leonardo da Vinci's fighting vehicle. Sloped armour was actually used on nineteenth century early Confederate ironclads, such as CSS Virginia, and partially implemented on the first French tank, the Schneider CA1 in the First World War, but the first tanks to be completely fitted with sloped armour were the French SOMUA S35 and other contemporary French tanks like the Renault R35, which had fully cast hulls and turrets. It was also used to a greater effect on the famous Soviet T-34 battle tank by the Soviet tank design team of the Kharkov Locomotive Factory, led by Mikhail Koshkin. It was a technological response to the more effective anti-tank guns being put into service at this time.

The T-34 had profound impact on German WWII tank design. Pre- or early war designs like the Panzer IV and Tiger differ clearly from post 1941 vehicles like for example the Panther, the Tiger II, the Jagdpanzer and the Hetzer, which all had sloped armour. This is especially evident because German tank armour was generally not cast but consisted of welded plates.

Sloped armour became very much the fashion after World War II, its most pure expression being perhaps the British Chieftain. However, the latest main battle tanks use perforated and composite armour, which attempts to deform and abrade a penetrator rather than deflecting it, as deflecting a long rod penetrator is difficult. These tanks have a more blocky appearance. Examples include the Leopard 2 and M1 Abrams. An exception is the Israeli Merkava.

References

- Yaziv, D.; Chocron, S.; Anderson, Jr., C.E.; Grosch, D.J. "Oblique Penetration in Ceramic Targets". Proceedings of the 19th International Symposium on Ballistics IBS 2001, Interlaken, Switzerland. pp. 1257–1264.

- Tate, A. (1979). "A simple estimate of the minimum target obliquity required for the ricochet of a high speed long rod projectile". Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics. 12 (11): 1825–1829. Bibcode:1979JPhD...12.1825T. doi:10.1088/0022-3727/12/11/011. S2CID 250808977.