The Holocaust in Slovakia

The Holocaust in Slovakia was the systematic dispossession, deportation, and murder of Jews in the Slovak State, a client state of Nazi Germany, during World War II. Out of 89,000 Jews in the country in 1940, an estimated 69,000 were murdered in the Holocaust.

After the September 1938 Munich Agreement, Slovakia unilaterally declared its autonomy within Czechoslovakia, but lost significant territory to Hungary in the First Vienna Award, signed in November. The following year, with German encouragement, the ruling ethnonationalist Slovak People's Party declared independence from Czechoslovakia. State propaganda blamed the Jews for the territorial losses. Jews were targeted for discrimination and harassment, including the confiscation of their property and businesses. The exclusion of Jews from the economy impoverished the community, which encouraged the government to conscript them for forced labor. On 9 September 1941, the government passed the Jewish Code, which it claimed to be the strictest anti-Jewish law in Europe.

In 1941, the Slovak government negotiated with Nazi Germany for the mass deportation of Jews to German-occupied Poland. Between March and October 1942, 58,000 Jews were deported to Auschwitz concentration camp and the Lublin District of the General Governorate; only a few hundred survived until the end of the war. The Slovak government organized the transports and paid 500 Reichsmarks per Jew for the supposed cost of resettlement. The persecution of Jews resumed in August 1944, when Germany invaded Slovakia and triggered the Slovak National Uprising. Another 13,500 Jews were deported and hundreds to thousands were murdered in Slovakia by Einsatzgruppe H and the Hlinka Guard Emergency Divisions.

After liberation by the Red Army, survivors faced renewed antisemitism and difficulty regaining stolen property; most emigrated after the 1948 Communist coup. The postwar Communist regime censored discussion of the Holocaust; free speech was restored after the fall of the Communist regime in 1989. The Slovak government's complicity in the Holocaust continues to be disputed by far-right nationalists.

Background

Before 1939, Slovakia had never been an independent country; its territory was part of the Kingdom of Hungary for a thousand years.[1][2] Seventeen medieval Jewish communities have been documented in the territory of modern-day Slovakia,[3] but significant Jewish presence was ended with the expulsions following the Hungarian defeat at the Battle of Mohács in 1526.[4] Many Jews immigrated in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Jews from Moravia settled west of the Tatra Mountains, forming the Oberlander Jews, while Jews from Galicia settled east of the mountains, forming a separate community (Unterlander Jews) influenced by Hasidism.[5][6] Due to the schism in Hungarian Jewry, communities split in the mid-nineteenth century into Orthodox (the majority), Status Quo, and more assimilated Neolog factions. Following Jewish emancipation, complete by 1896, many Jews adopted the Hungarian language and customs to advance in society.[1][6]

Although they were not as integrated as the Jews of Bohemia and Moravia, many Slovak Jews moved to cities and joined all the professions; others remained in the countryside, mostly working as artisans, merchants, and shopkeepers. Jews spearheaded the nineteenth-century economic changes that led to greater commerce in rural areas; by the end of the century some 70 percent of the bankers and businessmen in the Slovak uplands were Jewish.[7][6] Although a few Jews supported Slovak nationalism, by the mid-nineteenth century antisemitism had become a theme in the Slovak national movement, Jews being branded "agents of magyarization" and "the most powerful prop to the [Hungarian] ruling classes", in the words of historian Thomas Lorman.[1][6][8] In the western Slovak lands, anti-Jewish riots broke out in the wake of the Revolutions of 1848;[9] more riots occurred due to the Tiszaeszlár blood libel in 1882–1883.[8] Traditional religious antisemitism was joined by the stereotypical view of Jews as exploiters of poor Slovaks (economic antisemitism), and national antisemitism: Jews were strongly associated with the Hungarian state and accused of sympathizing with Hungarian at the expense of Slovak ambitions.[10][7][11]

After World War I, Slovakia became part of the new country of Czechoslovakia. Jews lived in 227 communities (in 1918) and their population was estimated at 135,918 (in 1921).[12] Anti-Jewish riots broke out in the aftermath of the declaration of independence (1918–1920), although the violence was not nearly as serious as in Ukraine or Poland.[13] Slovak nationalists associated Jews with the Czechoslovak state and accused them of supporting Czechoslovakism. Blood libel accusations occurred in Trenčin and in Šalavský Gemer in the 1920s. In the 1930s, the Great Depression affected Jewish businessmen and also increased economic antisemitism.[12] Economic underdevelopment and perceptions of discrimination in Czechoslovakia led a plurality (about one-third) of Slovaks to support the conservative, ethnonationalist Slovak People's Party (Slovak: Hlinkova slovenská ľudová strana: HSĽS).[14][15][16] HSĽS viewed minority groups such as Czechs, Hungarians, Jews, and Romani people as a destructive influence on the Slovak nation,[16] and presented Slovak autonomy as the solution to Slovakia's problems.[15] The party began to emphasize antisemitism during the late 1930s following a wave of Jewish refugees from Austria in 1938 and anti-Jewish laws passed by Hungary, Poland, and Romania.[17]

Slovak independence

The September 1938 Munich Agreement ceded the Sudetenland, the German-speaking region of the Czech lands, to Germany. HSĽS took advantage of the ensuing political chaos to declare Slovakia's autonomy on 6 October. Jozef Tiso, a Catholic priest and HSĽS leader, became prime minister of the Slovak autonomous region.[14][18] Catholicism, the religion of 80 percent of the country's inhabitants, was key to the regime with many of its leaders being bishops, priests, or laymen.[19][20][21] Under Tiso's leadership, the Slovak government opened negotiations in Komárno with Hungary regarding their border. The dispute was submitted to arbitration in Vienna by Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. Hungary was awarded much of southern Slovakia on 2 November, including 40 percent of Slovakia's arable land and 270,000 people who had declared Czechoslovak ethnicity.[22][23]

HSĽS consolidated its power by passing an enabling act, banning opposition parties, shutting down independent newspapers, distributing antisemitic and anti-Czech propaganda, and founding the paramilitary Hlinka Guard.[14][24] Parties for the German and Hungarian minorities were allowed under HSĽS hegemony, and the German Party formed the Freiwillige Schutzstaffel militia.[14][25] HSĽS imprisoned thousands of its political opponents,[26][27] but never carried out a sentence of capital punishment.[28] Un-free elections in December 1938 resulted in a 95-percent vote for HSĽS.[29][30]

On 14 March 1939, the Slovak State proclaimed its independence with German support and protection. Germany annexed and invaded the Czech rump state the following day, and Hungary seized Carpathian Ruthenia with German acquiescence.[18][29] In a treaty signed on 23 March, Slovakia renounced much of its foreign policy and military autonomy to Germany in exchange for border guarantees and economic assistance.[29][31] It was neither fully independent nor a German puppet state, but occupied an intermediate status.[lower-alpha 1] In October 1939, Tiso, leader of the conservative-clerical branch of HSĽS, became president; Vojtech Tuka, leader of the party's radical fascist wing, was appointed prime minister. Both wings of the party struggled for Germany's favor.[29][34] The radical wing of the party was pro-German, while the conservatives favored autonomy from Germany;[35][34] the radicals relied on the Hlinka Guard and German support,[34][36] while Tiso was popular among the clergy and the population.[37][38]

Anti-Jewish measures (1938–1941)

Initial actions

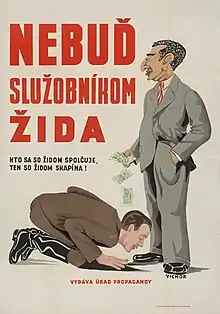

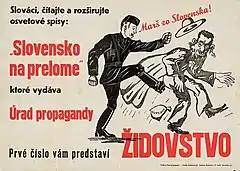

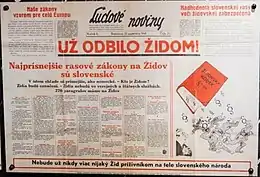

Immediately after Slovakia was established as a state in 1938, the government began firing its Jewish employees.[39] The Committee for the Solution of the Jewish Question was founded on 23 January 1939 to discuss anti-Jewish legislation.[26][40][41] The state-sponsored media demonized Jews as "enemies of the state" and of the Slovak nation.[40][42] Jewish businesses were robbed,[43] and physical attacks on Jews occurred both spontaneously and at the instigation of the Hlinka Guard and Freiwillige Schutzstaffel.[44] In his first radio address following the establishment of the Slovak State in 1939, Tiso emphasized his desire to "solve the Jewish Question";[45] anti-Jewish legislation was the only concrete measure that he promised.[46] The persecution of Jews was a key element of the state's domestic policy.[40][47] Discriminatory measures affected all aspects of life, serving to isolate and dispossess Jews before they were deported.[40]

In the days after the announcement of the First Vienna Award, antisemitic rioting broke out in Bratislava; newspapers justified the riots with Jews' alleged support for Hungary during the partition negotiations.[48] Adolf Eichmann, a Nazi official who had been sent to Bratislava, coauthored a plan with Tiso and other HSĽS politicians to deport impoverished and foreign Jews to the territory ceded to Hungary.[48][49] Meanwhile, Jews with a net worth of over 500,000 Czechoslovak koruna (Kčs) were arrested in an unsuccessful attempt to prevent capital flight. [40][48] Between 4 and 7 November,[40] 4,000[50] or 7,600 Jews were deported, in a chaotic, pogrom-like operation in which the Hlinka Guard, the Freiwillige Schutzstaffel, and the German Party participated.[49] The deportees included young children, the elderly, and pregnant women.[51] A few days later, Tiso canceled the operation; most of the Jews were allowed to return home in December.[26][52] More than 800 were confined to makeshift tent camps at Veľký Kýr, Miloslavov, and Šamorín on the new Slovak–Hungarian border during the winter.[53] The Slovak deportations occurred just after Germany's deportation of thousands of Polish Jews,[49][54] attracted international criticism,[40] reduced British investment, increased dependence on German capital,[55] and were a rehearsal for the 1942 deportations.[56]

Initially, many Jews believed that the measures taken against them would be temporary.[57] Nevertheless, some attempted to emigrate and take their property with them. Between December 1938 and February 1939, more than 2.25 million Kčs were transferred illegally to the Czech lands, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom; further amounts were transferred legally. Slovak government officials took advantage of the circumstances to purchase the property of wealthy Jewish emigrants at a significant discount, a precursor to the state-sponsored transfer of Jewish property as part of Aryanization.[58] Interest in emigration among Jews surged after the invasion of Poland, as Jewish refugees from Poland told of atrocities there.[57] Although the Slovak government encouraged Jews to emigrate, it refused to allow the export of foreign currency, ensuring that most attempts remained unsuccessful. No country was eager to accept Jewish refugees, and the tight limits imposed by the United Kingdom on legal emigration to Mandatory Palestine prevented Jews from seeking refuge there. In 1940, Bratislava became a hub for Aliyah Bet operatives organizing illegal immigration to Palestine, one of whom, Aron Grünhut, helped 1,365 Slovak, Czech, Hungarian, and Austrian Jews emigrate. By early 1941, further emigration was impossible; even Jews who received valid United States visas were not allowed transit visas through Germany.[57] The total number of Slovak Jewish emigrants has been estimated at 5,000 to 6,000.[59][60] As 45,000 lived in the areas ceded to Hungary,[59][60] the 1940 census found that 89,000 Jews lived in the Slovak State, 3.4 percent of the population.[61]

Aryanization

Aryanization in Slovakia, the seizure of Jewish-owned property and exclusion of Jews from the economy,[62][63] was justified by the stereotype (reinforced by HSĽS propaganda) of Jews obtaining their wealth by oppressing Slovaks.[64][65][66] Between 1939 and 1942, the HSĽS regime received widespread popular support by promising Slovak citizens that they would be enriched by property confiscated from Jews and other minorities.[64][67][68] They stood to gain a significant amount of money; in 1940, Jews registered more than 4.322 billion Slovak koruna (Ks) in property (38 percent of the national wealth).[69][lower-alpha 2] The process is also described as "Slovakization",[72][73] as the Slovak government took steps to ensure that ethnic Slovaks, rather than Germans or other minorities, received the stolen Jewish property. Due to the intervention of the German Party and Nazi Germany, ethnic Germans received 8.3 percent of the stolen property,[74][72] but most German applicants were refused, underscoring the freedom of action of the Slovak government.[74]

The first anti-Jewish law, passed on 18 April 1939 and not systematically enforced, was a numerus clausus four-percent quota of the numbers of Jews allowed to practice law; Jews were also forbidden to write for non-Jewish publications.[61][75][76] The Land Reform Act of February 1940 turned 101,423 hectares (250,620 acres) of land owned by 4,943 Jews, more than 40 percent of it arable, over to the State Land Office; the land officially passed to the state in May 1942.[69][lower-alpha 3] The First Aryanization Law was passed in April 1940. Through a process known as "voluntary Aryanization", Jewish business owners could suggest a "qualified Christian candidate" who would assume at least a 51-percent stake in the company.[61] Under the law, 50 businesses out of more than 12,000 were Aryanized and 179 were liquidated.[78] HSĽS radicals[61] and the Slovak State's German backers believed that voluntary Aryanization was too soft on the Jews.[79] Nevertheless, by mid-1940 the position of Jews in the Slovak economy had been largely wiped out.[63]

.jpg.webp)

At the July 1940 Salzburg Conference, Germany demanded the replacement of several members of the cabinet with reliably pro-German radicals.[80][81] Ferdinand Ďurčanský was replaced as interior minister by Alexander Mach, who aligned the anti-Jewish policy of the Slovak State with that of Germany.[82][83] Another result of the Salzburg talks was the appointment of SS officer Dieter Wisliceny as an adviser on Jewish affairs for Slovakia, arriving in August.[84][82] He aimed to impoverish the Jewish community so it would become a burden on non-Jewish Slovaks, who would then agree to deport them.[85] At Wisliceny's instigation, the Slovak government created the Central Economic Office (ÚHÚ), led by Slovak official Augustín Morávek and under Tuka's control, in September 1940.[82][86] The Central Economic Office was tasked with assuming ownership of Jewish-owned property.[61] Jews were required to register their property; their bank accounts (valued at 245 million Ks in August 1941)[lower-alpha 4] were frozen, and Jews were allowed to withdraw only 1,000 Ks (later 150 Ks) per week.[61][69] The 22,000 Jews who worked in salaried employment were targeted:[87] non-Jews had to obtain Central Economic Office permission to employ Jews and pay a fee.[61]

A second Aryanization law was passed in November, mandating the expropriation of Jewish property and the Aryanization or liquidation of Jewish businesses.[61][88] In a corrupt process overseen by Morávek's office, 10,000 Jewish businesses (mostly shops) were liquidated and the remainder – about 2,300 – were Aryanized.[61][69][89] Liquidation benefited small Slovak businesses competing with Jewish enterprises, and Aryanization was applied to larger Jewish-owned companies which were acquired by competitors. In many cases, Aryanizers inexpert in business struck deals with former Jewish owners and employees so the Jews would keep working for the company.[90][91] The Aryanization of businesses did not bring the anticipated revenue into the Slovak treasury, and only 288 of the liquidated businesses produced income for the state by July 1942.[92] The Aryanization and liquidation of businesses was nearly complete by January 1942,[90] resulting in 64,000 of 89,000 Jews losing their means of support.[93][94] For Jews, Aryanization resulted in disaster as the manufactured Jewish impoverishment was resolved by their deportation in 1942.[68][95][96]

Aryanization resulted in an immense financial loss for Slovakia and great destruction of wealth. The state failed to raise substantial funds from the sale of Jewish property and businesses, and most of its gains came from the confiscation of Jewish-owned bank accounts and financial securities. The main beneficiaries of Aryanization were members of Slovak fascist political parties and paramilitary groups, who were eager to acquire Jewish property but had little expertise in running businesses.[92][97] During the Slovak Republic's existence, the government gained 1,100 million Ks from Aryanization and spent 900–950 million Ks on enforcing anti-Jewish measures.[lower-alpha 5] In 1942, it paid the German government another 300 million Ks for the deportation of 58,000 Jews.[95]

Jewish Center

When Wisliceny arrived, all Jewish community organizations were dissolved and the Jews were forced to form the Ústredňa Židov (Jewish Center, ÚŽ, subordinate to the Central Economic Office) in September 1940.[98][82] The first Judenrat outside the Reich and German-occupied Poland, the ÚŽ was the only secular Jewish organization allowed to exist in Slovakia; membership was required of all Jews.[61][99] Leaders of the Jewish community were divided about how to respond to this development. Although some argued that the ÚŽ would be used to implement anti-Jewish measures, more saw participation in the ÚŽ as a way to help their fellow Jews by delaying the implementation of such measures and alleviating poverty.[98][100] The first leader of the ÚŽ was Heinrich Schwartz, who thwarted anti-Jewish orders to the best of his ability: he sabotaged a census of Jews in eastern Slovakia which was intended to justify their removal to the west of the country; Wisliceny had him arrested in April 1941.[101][102][103] The Central Economic Office appointed the more cooperative Arpad Sebestyen as Schwartz's replacement.[104] Wisliceny set up a Department for Special Affairs in the ÚŽ to ensure the prompt implementation of Nazi decrees, appointing the collaborationist Karol Hochberg (a Viennese Jew) as its director.[101][104]

Forced labor

Jews serving in the army were segregated into a labor unit in April 1939 and were stripped of their rank at the end of the year. From 1940, male Jews and Romani people were obliged to work for the national defense (generally manual labor on construction projects) for two months every year. All recruits considered Jewish or Romani were allocated to the Sixth Labor Battalion, which worked at military construction sites at Sabinov, Liptovský Svätý Peter, Láb, Svätý Jur, and Zohor the following year.[61] Although the Ministry of Defense was pressured by the Ministry of the Interior to release the Jews for deportation in 1942, it refused.[105] The battalion was disbanded in 1943, and the Jewish laborers were sent to work camps.[61][96]

The first labor centers were established in early 1941 by the ÚŽ as retraining courses for Jews forced into unemployment; 13,612 Jews had applied for the courses by February, far exceeding the programs' capacity.[106] On 4 July, the Slovak government issued a decree conscripting all Jewish men aged 18 to 60 for labor.[93][107] Although the ÚŽ had to supplement the workers' pay to meet the legal minimum, the labor camps greatly increased the living standard of Jews impoverished by Aryanization.[108] By September, 5,500 Jews were performing manual labor for private companies at about 80 small labor centers,[93] most of which were dissolved in the final months of 1941 as part of the preparation for deportation. Construction began on three larger camps – Sereď, Nováky, and Vyhne – in September of that year.[108][109]

Jewish Code

In accordance with Catholic teaching on race, antisemitic laws initially defined Jews by religion rather than ancestry; Jews who were baptized before 1918 were considered Christian.[61][79][110] By September 1940, Jews were banned from secondary and higher education and from all non-Jewish schools, and forbidden from owning motor vehicles, sports equipment, or radios.[85][74] Local authorities had imposed anti-Jewish measures on their own; the head of the Šariš-Zemplín region ordered local Jews to wear a yellow band around their left arm from 5 April 1941, leading to physical attacks against Jews.[61][111] In mid-1941, as the focus shifted to restricting Jews' civil rights after they had been deprived of their property through Aryanization, Department 14 of the Ministry of the Interior was formed to enforce anti-Jewish measures.[112]

The Slovak parliament passed the Jewish Code on 9 September 1941, which contained 270 anti-Jewish articles.[93] Based on the Nuremberg Laws, the code defined Jews in terms of ancestry, banned intermarriage, and required that all Jews over six years old wear a yellow star. The Jewish Code excluded Jews from public life, restricting the hours that they were allowed to travel and shop, and barring them from clubs, organizations, and public events.[93][113] Jews also had to pay a 20-percent tax on all property.[111] Government propaganda boasted that the Jewish Code was the strictest set of anti-Jewish laws in Europe. The president could issue exemptions protecting individual Jews from the law.[93] Employed Jews were initially exempt from some of the code's requirements, such as wearing the star.[114]

The racial definition of Jews was criticized by the Catholic Church, and converts were eventually exempted from some of the requirements.[115][116] The Hlinka Guard and Freiwillige Schutzstaffel increased assaults on Jews, engaged in antisemitic demonstrations on a daily basis, and harassed non-Jews judged insufficiently antisemitic.[117] The law enabled the Central Economic Office to force Jews to change their residence.[118] This provision was put into effect on 4 October 1941, when 10,000 of 15,000 Jews in Bratislava (who were not employed or intermarried) were ordered to move to fourteen towns.[118][119] The relocation was paid for and carried out by the ÚŽ's Department of Special Tasks.[120] Although the Jews were ordered to leave by 31 December, fewer than 7,000 people had moved by March 1942.[121][122]

Deportations (1942)

Planning

The highest levels of the Slovak government were aware by late 1941 of mass murders of Jews in German-occupied territories.[123][124] In July 1941, Wisliceny organized a visit by Slovak government officials to several camps run by Organization Schmelt, which imprisoned Jews in East Upper Silesia to employ them in forced labor on the Reichsautobahn. The visitors understood that Jews in the camps lived under conditions which would eventually cause their deaths.[88][125] Slovak soldiers participated in the invasions of Poland and the Soviet Union;[21] they brought word of the mass shootings of Jews, and participated in at least one of the massacres.[126] Some Slovaks were aware of the 1941 Kamianets-Podilskyi massacre, in which 23,600 Jews, many of them deported from Hungary, were shot in western Ukraine.[127][128] Defense minister Ferdinand Čatloš and General Jozef Turanec reported massacres in Zhytomyr to Tiso by February 1942.[123][129] Both bishop Karol Kmeťko and papal chargé d'affaires Giuseppe Burzio confronted the president with reliable reports of the mass murder of Jewish civilians in the Ukraine.[129][130] Slovak newspapers wrote many articles attempting to refute rumors that deported Jews were mistreated, pointing to general knowledge by mid-1942 that deported Jews were no longer alive.[131]

In mid-1941, the Germans demanded (per previous agreements) another 20,000 Slovak laborers to work in Germany. Slovakia refused to send gentile Slovaks and instead offered an equal number of Jewish workers, although it did not want to be burdened with their families.[132][84] A letter sent on 15 October 1941 indicates that plans were being made for the mass murder of Jews in the Lublin District of the General Government to make room for deported Jews from Slovakia and Germany.[133] In late October, Tiso, Tuka, Mach, and Čatloš visited the Wolf's Lair (near Rastenburg, East Prussia) and met with Adolf Hitler. No record survives of this meeting, at which the deportation of Jews from Slovakia was probably first discussed, leading to historiographical debate over who proposed the idea.[134][93] Even if the Germans made the offer, the Slovak decision was not motivated by German pressure.[129][135][136] In November 1941, the Slovak government permitted the German government to deport the 659 Slovak Jews living in the Reich and the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia to German-occupied Poland,[93][137] with the proviso that their confiscated property be passed to Slovakia.[138] This was the first step towards deporting Jews from Slovakia,[93][139] which Tuka discussed with Wisliceny in early 1942.[140] As indicated by a cable from the German ambassador to Slovakia, Hanns Ludin, the Slovaks responded "with enthusiasm" to the idea.[141]

Would [HSĽS politicians] let their wives get into a railway cattle car with five small children somewhere in Michalovce so they could ride for twenty hours on the floor of the train – only to get to Bratislava – let alone to Auschwitz or Lublin in occupied Poland? Would they agree that it is "normal" for their eighty-year old parents to be transported in the same fashion? Would they survive such a trip?

Slovak historian Eduard Nižňanský[142]

Tuka presented the deportation proposals to the government on 3 March, and they were debated in parliament three days later.[93] On 15 May, parliament approved Decree 68/1942, which retroactively legalized the deportation of Jews, authorized the removal of their citizenship, and regulated exemptions.[129][143][144] Opposition centered on economic, moral, and legal obstacles, but, as Mach later stated, "every [legislator] who has spoken on this issue has said that we should get rid of Jews".[145] The official Catholic representative and Bishop of Spiš, Ján Vojtaššák, only requested separate settlements in Poland for Jews who had converted to Christianity.[146] The Slovaks agreed to pay 500 Reichsmarks per Jew deported (ostensibly to cover shelter, food, retraining and housing)[146][147] and an additional fee to the Deutsche Reichsbahn for transport.[148] The 500 Reichsmark fee was equivalent to about USD$125 at the time,[70] or $2,200 today.[71] The Germans promised in exchange that the Jews would never return, and Slovakia could keep all confiscated property.[126][144] Except for the Independent State of Croatia (which paid 30 Reichsmarks per person), Slovakia was the only country which paid to deport its Jewish population.[149][150] According to historian Donald Bloxham, "the fact that the Tiso regime let Germany do the dirty work should not conceal its desire to “cleanse” the economy and ultimately the society in the name of 'Christianization'".[151]

First phase

The original deportation plan, approved in February 1942, entailed the deportation of 7,000 women to Auschwitz and 13,000 men to Majdanek as forced laborers.[152][153] Department 14 organized the deportations,[154][129] while the Slovak Transport Ministry provided the cattle cars.[155][156][144] Lists of those to be deported were drawn up by Department 14 based on statistical data provided by the Jewish Center's Department for Special Tasks.[153] At the border station in Zwardon, the Hlinka Guard handed the transports off to the German Schutzpolizei.[146][157] Slovak officials promised that deportees would be allowed to return home after a fixed period,[158] and many Jews initially believed that it was better to report for deportation rather than risk reprisals against their families.[159] On 25 March 1942, the first transport departed from Poprad transit camp for Auschwitz with 1,000 unmarried Jewish women between the ages of 16 and 45.[129] During the first wave of deportations (which ended on 2 April), 6,000 young, single Jews were deported to Auschwitz and Majdanek.[160]

Members of the Hlinka Guard, the Freiwillige Schutzstaffel, and the gendarmerie were in charge of rounding up the Jews, guarding the transit centers, and eventually forcing them into train cars for deportation.[129][161] A German officer was stationed at each of the concentration centers.[162] Official exemptions were supposed to keep certain Jews from being deported, but local authorities sometimes deported exemption-holders.[163] The victims were given only four hours' warning, to prevent them from escaping. Beatings and forcible shaving were commonplace, as was subjecting Jews to invasive searches to uncover hidden valuables.[164] Although some guards and local officials accepted bribes to keep Jews off the transports, the victim would typically be deported on the next train.[165] Others took advantage of their power to rape Jewish women.[166] Jews were only allowed to bring 50 kilograms (110 lb) of personal items with them, but even this was frequently stolen.[162]

Family transports

Reinhard Heydrich, the head of the Reich Security Main Office,[167] visited Bratislava on 10 April, and he and Tuka agreed that further deportations would target whole families and eventually remove all Jews from Slovakia.[168][169] The family transports began on 11 April, and took their victims to the Lublin District.[170][171] During the first half of June 1942 ten transports stopped briefly at Majdanek, where able-bodied men were selected for labor; the trains continued to Sobibor extermination camp, where the remaining victims were murdered.[170] Most of the trains brought their victims (30,000 in total)[172] to ghettos whose inhabitants had been recently deported to the Bełżec or Sobibor extermination camps. Some groups stayed only briefly before they were deported again to the extermination camps, while other groups remained in the ghettos for months or years.[170] Some of the deportees ended up in the forced-labor camps in the Lublin District (such as Poniatowa, Dęblin–Irena, and Krychów).[173] Unusually, the deportees in the Lublin District were quickly able to establish contact with the Jews remaining in Slovakia, which led to extensive aid efforts.[174] The fate of the Jews deported from Slovakia was ultimately "sealed within the framework of Operation Reinhard" along with that of the Polish Jews, in the words of Yehoshua Büchler.[157]

Transports went to Auschwitz after mid-June, where a minority of the victims were selected for labor and the remainder were killed in the gas chambers.[175][176] This occurred for nine transports, the last of which arrived on 21 October 1942.[176][177] From 1 August to 18 September, no transports departed;[178][177][176] most of the Jews not exempt from deportation had already been deported or had fled to Hungary.[179] In mid-August, Tiso gave a speech in Holič in which he described Jews as the "eternal enemy" and justified the deportations according to Christian ethics.[129][180] At this time of the speech, the Slovak government had accurate information on the mass murder of the deportees from Slovakia; an official request to inspect the camps where Slovak Jews were held in Poland was denied by Eichmann.[181] Three more transports occurred in September and October 1942 before ceasing until 1944.[182][177][176] By the end of 1942, only 500 or 600 Slovak Jews were still alive at Auschwitz.[144] Thousands of surviving Slovak Jews in the Lublin District were shot on 3–4 November 1943 during Operation Harvest Festival.[144][174]

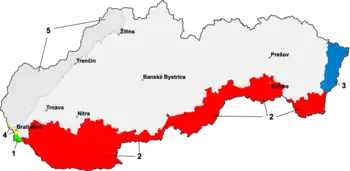

Between 25 March and 20 October 1942, almost 58,000 Jews (two-thirds of the population) were deported.[175][183][184] The exact number is unknown due to discrepancies in the sources.[185] The deportations disproportionately affected poorer Jews from eastern Slovakia. Although the Šariš-Zemplín region in eastern Slovakia lost 85 to 90 percent of its Jewish population, Žilina reported that almost half of its Jews remained after the deportation.[186][187][143] The deportees were held briefly in five camps in Slovakia before deportation;[162] 26,384 from Žilina,[188] 7,500 from Patrónka,[189] 7,000 from Poprad,[190] 4,463 from Sereď,[191] and 4,000 to 5,000 from Nováky.[192] Nineteen trains went to Auschwitz, and another thirty-eight went to ghettos and concentration and extermination camps in the Lublin District.[193] Only a few hundred survived the war,[129] most at Auschwitz; almost no one survived in Lublin District.[194]

Opposition, exemption, and evasion

The Holy See opposed deportation, fearing that such actions from a Catholic government would discredit the church.[195][130] Domenico Tardini, Vatican Undersecretary of State, wrote in a private memo: "Everyone understands that the Holy See cannot stop Hitler. But who can understand that it does not know how to rein in a priest?"[130][196] According to a Security Service (SD) report, Burzio threatened Tiso with an interdict.[129][130] Slovak bishops were equivocal, endorsing Jewish deicide and other antisemitic myths while urging Catholics to treat Jews humanely.[197] The Catholic Church ultimately chose not to discipline any of the Slovak Catholics who were complicit in the regime's actions.[198] Officials from the ÚŽ[199] and several of the most influential Slovak rabbis sent petitions to Tiso, but he did not reply.[200] Ludin reported that the deportations were "very unpopular",[96][195] but few Slovaks took action against them.[195][201] By March 1942, the Working Group (an underground organization which operated under the auspices of the ÚŽ) had formed to oppose the deportations. Its leaders, Zionist organizer Gisi Fleischmann and Orthodox rabbi Michael Dov Weissmandl, bribed Anton Vašek, head of Department 14, and Wisliceny. It is unknown if the group's efforts had any connection with the halting of deportations.[202][175][203]

Many Jews learned about the fate awaiting them during the first half of 1942, from sources such as letters from deported Jews or escapees.[204][205] Around 5,000 to 6,000 Jews fled to Hungary to avoid the deportations,[129][206][91] many by paying bribes[206] or with help from paid smugglers[207] and the Zionist youth movement Hashomer Hatzair;[96] about one third of those who fled to Hungary survived the war.[208] Many owners of Aryanized businesses applied for work exemptions for the Jewish former owners. In some cases this was a fictitious Aryanization; other Aryanizers, motivated by profit, kept the Jewish former owners around for their skills.[209][210] About 2,000 Jews had false papers identifying themselves as Aryans.[91] Some Christian clergy baptized Jews, even those who were not sincere converts. Although conversion after 1939 did not exempt Jews from deportation, being baptized made it easier to obtain other exemptions and some clergy edited records to predate baptisms.[211][198]

After the deportations, between 22,000 and 25,000 Jews were still in Slovakia.[212][213] Some 16,000 Jews had exemptions; there were 4,217 converts to Christianity before 1939, at least 985 Jews in mixed marriages,[214][215] and 9,687 holders of economic exemptions[214] (particularly doctors, pharmacists, engineers, and agricultural experts, whose professions had shortages).[216] One thousand Jews were protected by presidential exemptions, mostly in addition to other exemptions.[217][218] As well as the exempted Jews, around 2,500 were interned in labor camps,[212] and a thousand were serving in the Sixth Labor Battalion.[96] When the deportations were halted, the government knew the whereabouts of only 2,500 Jews without exemptions.[219]

Hiatus (1943)

During 1943, enforcement of anti-Jewish laws lessened, and many Jews stopped wearing the yellow star.[220] Nevertheless, the remaining Jews – even those with exemptions – lived in constant fear of deportation.[202][221] The ÚŽ worked to improve conditions for laborers in the Slovak camps[222][202] and to increase productivity, to strengthen the incentive to keep their workers in Slovakia.[216][223] In 1943, the labor camps earned 39 million Ks for the Slovak State.[224][212][lower-alpha 6] The halt in deportations from Slovakia enabled the Working Group to launch the Europa Plan, an unsuccessful effort to bribe SS chief Heinrich Himmler to spare the surviving Jews under German occupation.[202][225] It also smuggled aid to Jews in Poland,[226][227] and helped Polish Jews escape to Hungary via Slovakia.[228][229] In late April 1944 two Auschwitz escapees, Rudolf Vrba and Alfred Wetzler, reached Slovakia.[230] The Working Group sent their report to Hungary and Switzerland; it reached the Western Allies in July.[231]

After the Battle of Stalingrad and other reversals in the increasingly unpopular war in the east, Slovak politicians realized that a German defeat was likely.[232][127] Some HSĽS politicians (especially those in the radical faction) blamed economic setbacks on the Jews and agitated for the deportation of the remaining population.[233] On 7 February 1943, Mach announced at a rally in Ružomberok that the transports would soon resume.[234] In early 1943, the Hlinka Guard and Department 14 prepared for the resumption of deportations: registering Jews, canceling economic exemptions, and hunting down Jews in hiding.[235] A plan to dispatch four trains between 18 and 22 April was not implemented.[236] In response to the threatened resumption, Slovak bishops issued a pastoral letter in Latin on 8 March condemning antisemitism and totalitarianism and defending the rights of all Jews.[237][238] Germany put increasing pressure on the Slovak State to hand over its remaining Jews in 1943 and 1944, but Slovak politicians did not agree to resume the deportations.[239]

In late 1943, leading army officers and intelligentsia formed the Slovak National Council to plan an insurrection; the council united both Communist and democratic opponents of the regime.[240] Other anti-fascists retreated to the Carpathian mountains and formed partisan groups.[241][242] Preparations for the uprising evoked mixed feelings in the remaining Slovak Jews, who feared that an uprising would bring about a crackdown on their community.[242] Underground groups organized at the Sereď[243][244] and Nováky labor camps.[245][244] Slovak authorities began to re-register Jews in January 1944, prompting some to flee to Hungary.[246] On 19 March 1944 Germany invaded Hungary, including Carpathian Ruthenia and the areas ceded by Czechoslovakia in 1938.[247][248] The Slovak Jews who had fled to Hungary tried to return, but many were arrested at the border and deported directly to Auschwitz.[242] The Slovak ambassador in Budapest, Ján Spišiak, issued documents to 3,000 Jews allowing them to legally cross the border,[241] bringing the total number of Jews in Slovakia to 25,000.[242] Between 14 May and 7 July 437,000 Jews were deported from Hungary, most to Auschwitz;[249] including many Slovak Jews in the country.[241] To counter the perceived security threat of Jews in the Šariš-Zemplín region with the front line moving westward, on 15 May 1944 the Slovak government ordered Jews to move to the western part of the country.[250]

Resumption of deportations (1944–1945)

German invasion

Concerned about the increase in resistance, Germany invaded Slovakia; this precipitated the Slovak National Uprising, which broke out on 29 August 1944.[251][252][253] The insurgent forces seized central Slovakia but were defeated on 27 October at Banská Bystrica. Partisans withdrew to the mountains and continued their guerrilla campaign into 1945.[251][254] A new government was sworn in, with Tiso's cousin Štefan as prime minister; Jozef remained president.[255][256] The papal chargé d'affaires Burzio met with Tiso on 22 and 29 September, reportedly calling Tiso a liar when the president denied knowledge of deportations.[257][258] Pius XII instructed Burzio to tell Tiso that the Vatican condemned the persecution of individuals for their race or nationality.[259][260] The United States and Switzerland issued formal protests against the deportation of Jews.[258] Slovak propaganda blamed the Jews and Czechs for the uprising.[261][262] Nevertheless, the Slovak government preferred the concentration of Jews in concentration camps in Slovakia to their deportation.[262] Tiso asked for the Germans to spare at least baptized Jews and those in mixed marriages, but his requests were ignored.[257]

The uprising provided the Germans with an opportunity to implement the Final Solution in Slovakia.[263] Anti-Jewish actions were nominally controlled by the Slovak Ministry of Defense, but in practice the Germans dictated policy.[255][264] Unlike the deportations of 1942, the roundups of Jews were organized and carried out by German forces.[263] SS officer Alois Brunner, who had participated in the organization of transports of Jews from France and Greece,[265][266] arrived in Slovakia to arrange the deportation of the country's remaining Jews.[266] The SS unit Einsatzgruppe H, including Einsatzkommandos 13, 14, and 29, was formed to suppress the uprising immediately after it began and round up Jews and Romani people.[264][267] Local collaborators, including SS-Heimatschutz (HS), Freiwillige Schutzstaffel and the Hlinka Guard Emergency Divisions (POHG),[264][268] were essential to Einsatzgruppe H's work.[264][269][270] Collaborators denounced those in hiding, impersonated partisans, and aided with interrogations.[269]

After the uprising began, thousands of Jews fled to the mountainous interior and partisan-controlled areas around Banská Bystrica,[242][241] including many who left the labor camps after the guards fled.[271] Around 1,600 to 2,000 Jews fought as partisans, ten percent of the total insurgent force,[272][241] although many hid their identity due to antisemitism in the partisan movement.[273] Anti-Jewish legislation in the liberated areas was canceled by the Slovak National Council,[241] but the attitude of the local population varied: some risked their lives to hide Jews, and others turned them in to the police.[274] Unlike in 1942, the death penalty was in effect for rescuers;[275] the majority provided help for a fee, although there were also cases of selfless rescues.[260][276] Many Jews spent six to eight months in makeshift shelters or bunkers in the mountains,[274][275] while others hid in the houses of non-Jews. Regardless, Jews required money for six to eight months of living expenses and the help of non-Jews willing to provide assistance.[277] Some of the Jews in shelters had to return home later in the winter, risking capture, because of the hunger and cold.[278][275] Living openly and continuing to work under false papers was typically only possible in Bratislava.[279]

Roundups

Jews who were captured were briefly imprisoned at local prisons or the Einsatzgruppe H office in Bratislava, from which they were sent to Sereď for deportation. Local authorities provided lists of Jews, and many local residents also denounced Jews.[274][280][279] In the first half of September there were large-scale raids in Topoľčany (3 September), Trenčín, and Nitra (7 September), during which 616 Jews were arrested and imprisoned in Ilava and Sereď.[255][281] In Žilina, Einsatzkommando 13 and collaborators arrested hundreds of Jews over the night of 13/14 September. The victims were deported to Sereď or Ilava and thence to Auschwitz, where most were murdered.[255][282] Einsatzgruppe H reported that some Jews were able to escape because of insufficient personnel, but that both Germans and Slovaks generally supported the roundups and helped track down evaders.[283] After the defeat of the uprising, the German forces also hunted the Jews hiding in the mountains.[284][279] Although most victims were arrested during the first two months of occupation, the hunt for the Jews continued until 30 March 1945, when a Jewish prisoner was taken to Sereď just three days before the camp was liberated.[274][285]

Half of Bratislava was on its feet this morning to watch the show of the Judenevakuierung ... so was the kick, administered by an S.S.-man to a tardy Jew received by the large crowd ... with hand claps and cries of support and encouragement.

Some Jews had been arrested in Bratislava by 20 September. The largest roundup was carried out in the city during the night of 28/29 September by Einsatzkommando 29, aided by 600 HS and POHG collaborators and a Luftwaffe unit that guarded the streets: around 1,600 Jews were arrested and taken to Sereď.[287][270][288] Some 300 Jews with foreign citizenship were temporarily housed in a castle in Marianka. Brunner raided the castle on 11 October; all but three of the prisoners were taken to Sereď and deported to Auschwitz on 17 October.[289][290] In mid-October, an office was established at the former Jewish Center to hunt down Jews in hiding, which tortured captured Jews into revealing the names and addresses of other Jews.[280] The one to two thousand Jews left in Bratislava were ordered to turn themselves in on 20 November or face imprisonment, but few did so.[291] Half of the Jews arrested after 19 November were in Bratislava, most in hiding with false papers.[292] Henri Dunand of the Red Cross provided funding for a clandestine group led by Arnold Lazar, which provided money, food, and clothing to Jews in hiding in Bratislava.[260]

Deportation

Sereď concentration camp was the primary facility for interning Jews before their deportation. Although there were no transports until the end of September, the Jews experienced harsh treatment (including rape and murder) and severe overcrowding as the population swelled to 3,000 – more than twice the intended capacity.[243][293][294] Brunner took over the camp's administration from the Slovak government at the end of September.[266] About 11,700 people were deported on eleven transports;[243][266] the first five (from 30 September to 17 October) went to Auschwitz, where most of the victims were gassed. The final transport to Auschwitz, on 2 November, arrived after the gas chambers were shut down. Later transports left for Sachsenhausen, Bergen-Belsen, Ravensbrück, and Theresienstadt.[275][295]

Two small transports left Čadca for Auschwitz on 1 and 5 September; Fatran estimates that the total number of deportees was about 400. In September and October, at least 131 people were deported from Slovakia via Zakopane; two of the transports ended at Kraków-Płaszów and the third at Auschwitz. A transport from Prešov, departing 26 November, ended up at Ravensbrück. According to a Czechoslovak criminal investigation, another 800 Jews were deported in two transports from eastern Slovakia on 16 October and 16 December. Details on the transports leaving from locations other than Sereď is fragmentary,[296] and the total number of deportees is not known.[263] Slovak historian Ivan Kamenec estimated that 13,500 Jews were deported in 1944 and 1945, of whom 10,000 died,[251][297][213] but Israeli historian Gila Fatran and Czech historian Lenka Šindelářová consider that 14,150 deportees can be verified and the true figure may be higher.[263][273] The Slovak regime also transferred several hundred political prisoners to German custody. Deported to Mauthausen concentration camp, many died there.[298]

Massacres

After the German invasion, about 4,000 people were murdered in Slovakia, mostly by Einsatzgruppe H, but with help from local collaborators.[299] About half (2,000) of the victims were Jews;[275][300][301] other victims included partisans, supporters of the uprising, and Romani people.[302] One of the first executions occurred in the Topoľčany district, where Einsatzkommando 14 began its mass roundups of Jews. Many of the arrested Jews were taken to Sereď for deportation, but 53 were shot in Nemčice on 11 September.[303] The largest execution was in Kremnička, a small village 6 kilometres (3.7 mi) away from Banská Bystrica. Upon the capture of the rebel stronghold, Jews, partisans, Romanis, and others arrested in the area were held in the prison in the town. Of these, 743 people were brought to Kremnička for execution in a series of massacres between November and March, by Einsatzgruppe H and the POHG. Victims included 280 women and 99 children; half were Jewish. Hundreds of people were murdered at the nearby village of Nemecká, where the victims' bodies were burned after they were shot.[269][304] Zvolen's Jewish cemetery was used as an execution site; 218 bodies were exhumed after the end of the war.[305]

Aftermath

The Red Army captured Slovakia by the end of April 1945.[306] Around 69,000 Jews, 77 percent of the prewar population, had been murdered.[307] In addition to the 10,000[308] to 11,000 Jews who survived in Slovakia, 9,000 Jews returned who had been deported to concentration camps or fled abroad, and 10,000 Jews survived in the Hungarian-annexed territories. By the end of 1945, 33,000 Jews were living in Slovakia. Many survivors had lost their entire families, and a third suffered from tuberculosis.[309] Although a postwar Czechoslovak law negated property transactions arising from Nazi persecution, the autonomous Slovak government refused to apply it.[310][311] Heirless property was nationalized in 1947 into the Currency Liquidation Fund.[310] Those who had stolen Jewish property were reluctant to return it; former resistance members had also appropriated some stolen property. Conflict over restitution led to intimidation and violent attacks, including the September 1945 Topoľčany pogrom and the Partisan Congress riots in August 1946.[312][313] Polish historian Anna Cichopek-Gajraj estimates that at least 36 Jews were murdered and more than 100 injured in postwar violence.[314][315]

Josef Witiska, the commander of Einsatzgruppe H, committed suicide in 1946 during extradition to Czechoslovakia;[316] Wisliceny was tried, convicted and executed in Bratislava in 1948.[317] Tiso (who had fled to Austria) was extradited to Czechoslovakia, convicted of treason and collaboration, sentenced to death on 15 April 1947, and executed three days later.[251] According to the court, his "most immoral, most unchristian, and most inhuman" action was ordering the deportation of the Slovak Jews.[318] Other perpetrators, including Tuka, were also tried, convicted, and executed.[319][320] Both Tiso and Tuka were tried under Decree 33/1945, an ex post facto law that mandated the death penalty for the suppression of the Slovak National Uprising;[321][322] their roles in the Holocaust were a subset of the crimes for which they were convicted.[318][323] The authors of some of the more egregious antisemitic articles and caricatures were prosecuted after the war.[324] The trials painted Slovak State officials as traitors, thereby exonerating Slovak society from responsibility for the Holocaust.[319]

The Czechoslovak government supported Zionism, insisting that Jews assimilate into Czechoslovak culture or emigrate to Palestine.[325] Jews who had declared German or Hungarian nationality on a prewar census were stripped of their citizenship, losing any right to restitution, and were threatened with deportation.[326] Most Jews in Slovakia emigrated to Israel or other countries in the years after the war. Emigration accelerated in 1948 after the Communist coup and nationalization of many businesses after the war. The number of Jewish communities decreased from the postwar high of 126 to 25, while the population decreased by 80 percent. Only a few thousand Jews were left by the end of 1949.[327] Many of those who chose to stay changed their surnames and abandoned religious practice to fit in with the Slovak middle class.[315] In 2019, the Jewish population was estimated at 2,000[310] to 3,000.[328]

Legacy

.jpg.webp)

The government's attitude to Jews and Zionism shifted after 1948, leading to the 1952 Slánský trial in which the Czechoslovak government accused fourteen Communists (eleven of them Jewish) of belonging to a Zionist conspiracy.[329][330] Political censorship hampered the study of the Holocaust, and memorials to the victims of fascism did not mention Jews. In the 1960s, which were characterized by a liberalization known as the Prague Spring, discussion of the Holocaust opened up.[331][332] The Academy Award-winning 1965 film, The Shop on Main Street, focused on Slovak culpability for the Holocaust.[332][333] Following the 1968 Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia, authorities cracked down on free expression,[334][335] while anti-Zionist propaganda, much of it imported from the Soviet Union, intensified and veered into antisemitism after Israeli victory in the 1967 Six-Day War.[336]

A nationalist resurgence followed the fall of the Communist regime in 1989, leading to the dissolution of Czechoslovakia in 1993 and the nationalist Mečiar government. After Mečiar's fall in 1998, the Slovak government promoted Holocaust remembrance to demonstrate the country's European identity before it joined the European Union in 2004.[337] During the 1990s, many memorials were constructed to commemorate Holocaust victims,[338][339] and in October 2001 Slovakia designated 9 September (the anniversary of the passage of the Jewish Code) as Holocaust Victims and Racial Hatred Day.[340] The National Memory Institute was established in 2002 to provide access to the records of both the Slovak State and Communist state.[341] The post-Communist government enacted laws for the restitution of Jewish property, but residency and citizenship requirements prevented emigrants from filing claims.[342] In 2002, ten percent of the value of the nationalized heirless property was released into a fund that paid for Jewish education and Holocaust memorials.[343] As of January 2019, Yad Vashem (the official Israeli memorial to the Holocaust) has recognized 602 Slovaks as Righteous Among the Nations for risking their lives to save Jews.[344]

Political scientist Jelena Subotić states that the Slovak State is "a paradox for postcommunist Slovakia’s identity construction" because it is seen as the first independent Slovak state. If considered fully independent, then it takes greater responsibility for the deportation of Jews during the Holocaust, but if not, then it loses its role as legitimation for the current Slovak state.[345] Holocaust relativism in Slovakia tends to manifest as attempts to absolve the Tiso government of blame by deflecting responsibility onto Germans and Jews.[51][136] A 1997 textbook by Milan Stanislav Ďurica and endorsed by the government sparked international controversy (and was eventually withdrawn from the school curriculum) because it portrayed Jews as living happily in labor camps during the war.[346][347][348] Tiso and the Slovak State have been the focus of Catholic and ultranationalist commemorations.[349][45] The neo-Nazi[350] Kotleba party, which is represented in the national parliament and the European Parliament and is especially popular with younger voters,[351] promotes a positive view of the Slovak State. Its leader, Marian Kotleba, once described Jews as "devils in human skin".[352] Members of the party have been charged with Holocaust denial,[353][354] which has been a criminal offense since 2001.[353]

Notes

- German historian Tatjana Tönsmeyer disagrees that the Tiso government was a puppet state because the Slovak authorities frequently avoided implementing measures pushed by the Germans when such measures did not suit Slovak priorities. According to German historian Barbara Hutzelmann, "Although the country was not independent, in the full sense of the word, it would be too simplistic to see this German-protected state (Schutzstaat) simply as a 'puppet regime'."[32] Ivan Kamenec emphasizes German influence on Slovak internal and external politics and describes it as a "German satellite".[33]

- Equivalent to USD$108 million at the time,[70] or $1,930,000,000 today.[71] All currency conversions are made from the Foreign Claims Settlement Commission's determination of wartime exchange rate.[70]

- The Land Reform Act did not explicitly target Jews, but it was rarely enforced against non-Jewish landowners.[63][77]

- Equivalent to USD$6.125 million at the time,[70] or $109,700,000 today.[71]

- Gain equivalent to USD$27.5 million at the time,[70] or $493,000,000 today.[71] Loss equivalent to $22.5 million[70] or $403,000,000 today.[71]

- Equivalent to USD$975,000 at the time,[70] or $17,500,000 today.[71]

References

Citations

- Hutzelmann 2018, p. 18.

- Ward 2013, p. 12.

- Borský 2005, p. 15.

- Borský 2005, pp. 16–17.

- Borský 2005, pp. 17–18, 20–21.

- Lorman 2019, pp. 47–48.

- Hutzelmann 2018, pp. 18–19.

- Klein-Pejšová 2015, p. 11.

- Dojc & Krausová 2011, p. 119.

- Láníček 2013, p. 35.

- Nižňanský 2014, pp. 49–50.

- Hutzelmann 2018, p. 19.

- Láníček 2013, pp. 6, 10.

- Rajcan, Vadkerty & Hlavinka 2018, p. 842.

- Ward 2015, p. 79.

- Paulovičová 2018, p. 5.

- Ward 2015, p. 87.

- Láníček 2013, pp. 16–17.

- Kamenec 2011a, pp. 179–180.

- Kornberg 2015, pp. 81–82.

- Hutzelmann 2018, p. 23.

- Ward 2013, pp. 161, 163, 166.

- Rajcan, Vadkerty & Hlavinka 2018, pp. 842–843.

- Hutzelmann 2018, p. 20.

- Hutzelmann 2018, pp. 20–21.

- Hutzelmann 2018, p. 22.

- Paulovičová 2012, p. 91.

- Ward 2013, p. 9.

- Rajcan, Vadkerty & Hlavinka 2018, p. 843.

- Lorman 2019, p. 216.

- Ward 2013, p. 184.

- Hutzelmann 2016, p. 168.

- Kamenec 2011a, pp. 180–182.

- Kamenec 2011a, p. 184.

- Ward 2013, p. 203.

- Ward 2013, p. 216.

- Kamenec 2011a, pp. 184–185.

- Ward 2013, pp. 172, 216.

- Ward 2013, p. 165.

- Rajcan, Vadkerty & Hlavinka 2018, p. 844.

- Hallon 2007, p. 149.

- Kamenec 2011a, p. 188.

- Legge 2018, p. 226.

- Paulovičová 2013, pp. 551–552.

- Paulovičová 2018, p. 11.

- Lorman 2019, p. 226.

- Paulovičová 2018, p. 8.

- Ward 2015, p. 92.

- Hutzelmann 2018, p. 21.

- Frankl 2019, p. 97.

- Kubátová 2014, p. 506.

- Ward 2015, p. 93.

- Frankl 2019, pp. 103, 112.

- Frankl 2019, p. 95.

- Ward 2015, p. 96.

- Johnson 2005, p. 316.

- Hutzelmann 2018, p. 26.

- Hallon 2007, pp. 149–150.

- Ward 2015, pp. 94, 96.

- Legge 2018, p. 227.

- Rajcan, Vadkerty & Hlavinka 2018, p. 845.

- Hallon 2007, p. 148.

- Hutzelmann 2018, p. 25.

- Lônčíková 2017, p. 85.

- Kubátová & Láníček 2018, p. 43.

- Tönsmeyer 2007, p. 90.

- Cichopek-Gajraj 2018, p. 254.

- Kubátová & Láníček 2018, p. 95.

- Dreyfus & Nižňanský 2011, p. 24.

- Foreign Claims Settlement Commission 1968, p. 655.

- Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis 2019.

- Hutzelmann 2016, p. 174.

- Kubátová 2014, p. 510.

- Hutzelmann 2018, p. 28.

- Rothkirchen 2001, pp. 596–597.

- Ward 2015, p. 97.

- Ward 2013, p. 221.

- Hallon 2007, p. 151.

- Hutzelmann 2016, p. 169.

- Kamenec 2011a, p. 177.

- Rajcan, Vadkerty & Hlavinka 2018, pp. 843–844.

- Hutzelmann 2018, p. 27.

- Legge 2018, p. 228.

- Bauer 1994, p. 65.

- Ward 2013, p. 215.

- Hutzelmann 2016, pp. 169–170.

- Hilberg 2003, p. 769.

- Hutzelmann 2016, p. 170.

- Hilberg 2003, pp. 769–770.

- Hilberg 2003, pp. 770–771.

- Nižňanský 2014, p. 70.

- Dreyfus & Nižňanský 2011, pp. 24–25.

- Rajcan, Vadkerty & Hlavinka 2018, p. 846.

- Dreyfus & Nižňanský 2011, p. 26.

- Dreyfus & Nižňanský 2011, p. 25.

- Hutzelmann 2018, p. 38.

- Hutzelmann 2016, pp. 173–174.

- Fatran 1994, p. 165.

- Bauer 2002, p. 176.

- Fatran 2002, p. 143.

- Fatran 1994, p. 166.

- Fatran 2002, pp. 144–145.

- Rothkirchen 2001, p. 597.

- Bauer 1994, p. 70.

- Bachnár 2011.

- Kamenec 2007, p. 177.

- Hutzelmann 2018, p. 30.

- Kamenec 2007, p. 180.

- Rajcan, Vadkerty & Hlavinka 2018, pp. 846–847.

- Hutzelmann 2018, pp. 24, 29.

- Hutzelmann 2018, p. 29.

- Kamenec 2007, p. 181.

- Kamenec 2011a, pp. 188–189.

- Hilberg 2003, p. 774.

- Paulovičová 2012, pp. 260–262.

- Ward 2013, p. 226.

- Kamenec 2007, pp. 186–187.

- Hilberg 2003, p. 775.

- Hradská 2016, pp. 315, 321.

- Kamenec 2007, pp. 191–192.

- Kamenec 2007, p. 192.

- Hradská 2016, p. 321.

- Hutzelmann 2018, p. 31.

- Hutzelmann 2016, p. 175.

- Hutzelmann 2018, pp. 30–31.

- Hutzelmann 2016, p. 176.

- Hutzelmann 2018, p. 39.

- Longerich 2010, p. 224.

- Rajcan, Vadkerty & Hlavinka 2018, p. 847.

- Ward 2013, p. 232.

- Kubátová & Láníček 2018, p. 107.

- Bauer 2002, pp. 176–177.

- Longerich 2010, pp. 295, 428.

- Paulovičová 2013, pp. 570, 572.

- Láníček 2013, p. 110.

- Paulovičová 2018, p. 10.

- Hilberg 2003, p. 463.

- Longerich 2010, p. 285.

- Nižňanský 2011, p. 114.

- Ward 2013, p. 229.

- Nižňanský 2011, p. 116.

- Nižňanský 2014, p. 87.

- Ward 2013, p. 233.

- Hutzelmann 2018, p. 34.

- Ward 2013, p. 230.

- Hutzelmann 2018, p. 32.

- Hilberg 2003, pp. 776–777.

- Hilberg 2003, p. 778.

- Nižňanský 2011, p. 121.

- Paulovičová 2013, p. 555.

- Bloxham 2017, p. 70.

- Longerich 2010, pp. 324–325.

- Büchler 1996, p. 301.

- Ward 2002, p. 576.

- Hilberg 2003, p. 777.

- Ward 2013, pp. 216, 230.

- Büchler 1991, p. 153.

- Büchler 1996, p. 302.

- Bauer 2002, pp. 177–178.

- Ward 2002, p. 579.

- Cichopek-Gajraj 2014, pp. 15–16.

- Nižňanský 2014, p. 66.

- Paulovičová 2012, p. 264.

- Sokolovič 2009, pp. 346–347.

- Kamenec 2011b, p. 107.

- Sokolovič 2009, p. 347.

- Longerich 2010, pp. 143–144.

- Longerich 2010, p. 325.

- Kamenec 2007, pp. 222–223.

- Longerich 2010, pp. 325–326.

- Büchler 1996, pp. 313, 320.

- Hilberg 2003, p. 785.

- Büchler 1991, pp. 159, 161.

- Büchler 1991, p. 160.

- Longerich 2010, p. 326.

- Büchler 1996, p. 320.

- Fatran 2007, p. 181.

- Bauer 1994, p. 96.

- Bauer 1994, pp. 75, 97.

- Ward 2013, pp. 8, 234.

- Ward 2013, p. 234.

- Ward 2013, p. 8.

- Kamenec 2011a, p. 189.

- Fatran 2007, pp. 180–181.

- Silberklang 2013, pp. 296–297.

- Ward 2002, p. 584.

- Putík 2015, p. 187.

- Rajcan 2018c, p. 889.

- Rajcan 2018a, p. 855.

- Rajcan 2018b, p. 879.

- Nižňanský, Rajcan & Hlavinka 2018b, p. 881.

- Nižňanský, Rajcan & Hlavinka 2018a, p. 874.

- Büchler 1991, p. 151.

- Putík 2015, p. 47.

- Kornberg 2015, p. 83.

- Kornberg 2015, pp. 83–84.

- Kornberg 2015, p. 82.

- Kornberg 2015, p. 84.

- Fatran 1994, p. 167.

- Kubátová 2014, pp. 514–515.

- Lônčíková 2017, p. 91.

- Rajcan, Vadkerty & Hlavinka 2018, p. 848.

- Fatran 1994, abstract.

- Paulovičová 2012, pp. 77–78.

- Bauer 1994, pp. 71–72.

- Kamenec 2011b, p. 110.

- Paulovičová 2012, p. 62, Chapter IV passim.

- Paulovičová 2012, p. 187.

- Nižňanský 2014, pp. 62, 70.

- Hutzelmann 2016, pp. 176, 178.

- Paulovičová 2012, pp. 279, 297.

- Hutzelmann 2018, p. 40.

- Ward 2002, p. 589.

- Bauer 1994, p. 97.

- Ward 2002, pp. 587–588.

- Kamenec 2011a, p. 190.

- Ward 2013, pp. 232–233.

- Ward 2002, pp. 583, 587.

- Ward 2013, p. 235.

- Kamenec 2007, p. 303.

- Kamenec 2007, pp. 283, 303.

- Rothkirchen 2001, p. 599.

- Kamenec 2007, pp. 315–316, 319.

- Hutzelmann 2016, p. 171.

- Bauer 1994, pp. 88–89, 99, Chapter 5–7 passim.

- Büchler 1991, p. 162.

- Fatran 1994, p. 178.

- Fatran 1994, p. 181.

- Paulovičová 2012, p. 229.

- Bauer 2002, p. 229.

- Bauer 2002, p. 237.

- Longerich 2010, p. 405.

- Kamenec 2007, pp. 280–281.

- Bauer 1994, p. 86.

- Kamenec 2007, pp. 284–285.

- Kamenec 2007, p. 286.

- Kornberg 2015, p. 85.

- Ward 2013, pp. 236, 238.

- Kamenec 2007, p. 203.

- Kamenec 2011a, p. 192.

- Hutzelmann 2018, p. 42.

- Fatran 1996, p. 99.

- Nižňanský, Rajcan & Hlavinka 2018b, p. 882.

- Hutzelmann 2018, p. 41.

- Nižňanský, Rajcan & Hlavinka 2018a, p. 876.

- Fatran 1994, p. 188.

- Bauer 2002, p. 226.

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

- Longerich 2010, p. 408.

- Fatran 1996, p. 113.

- Rajcan, Vadkerty & Hlavinka 2018, p. 849.

- Šindelářová 2013b, p. 585.

- Kubátová 2014, p. 515.

- Ward 2013, pp. 249–250, 252.

- Hutzelmann 2018, p. 43.

- Ward 2013, p. 249.

- Ward 2013, p. 251.

- Šindelářová 2013a, pp. 85–86.

- Šindelářová 2013a, p. 86.

- Hutzelmann 2018, p. 45.

- Kubátová 2014, p. 517.

- Šindelářová 2013a, p. 84.

- Šindelářová 2013a, p. 82.

- Fatran 1996, p. 101.

- Longerich 2010, pp. 391, 395, 403.

- Nižňanský 2014, p. 74.

- Šindelářová 2013b, p. 587.

- Putík 2015, p. 42.

- Šindelářová 2013b, p. 592.

- Nižňanský 2014, p. 73.

- Fatran 1996, pp. 100–101.

- Kubátová 2014, p. 516.

- Fatran 1996, p. 119.

- Šindelářová 2013b, p. 590.

- Hutzelmann 2018, p. 44.

- Nižňanský 2014, pp. 76–77.

- Fatran 1996, pp. 104–105.

- Fatran 1996, p. 105.

- Putík 2015, p. 52.

- Šindelářová 2013a, p. 93.

- Šindelářová 2013a, p. 88.

- Šindelářová 2013a, pp. 88–89.

- Šindelářová 2013a, p. 90.

- Šindelářová 2013a, pp. 92–93.

- Šindelářová 2013a, pp. 99–100.

- Aronson 2004, p. 177.

- Šindelářová 2013a, p. 89.

- Putík 2015, p. 53.

- Fatran 1996, p. 112.

- Hlavinka 2018, p. 871.

- Šindelářová 2013a, pp. 91–92.

- Putík 2015, pp. 52, 211.

- Fatran 1996, p. 102.

- Šindelářová 2013a, pp. 96–97, 99.

- Putík 2015, pp. 54, 68–69.

- Šindelářová 2013a, p. 104.

- Kamenec 2007, p. 337.

- Ward 2013, p. 256.

- Šindelářová 2013a, pp. 105–106.

- Ward 2013, p. 253.

- Šindelářová 2013a, p. 106.

- Šindelářová 2013a, p. 105.

- Šindelářová 2013a, pp. 107–108.

- Šindelářová 2013a, p. 115.

- Fatran 1996, p. 115.

- Cichopek-Gajraj 2014, p. 31.

- Cichopek-Gajraj 2014, p. 19.

- Kubátová 2014, p. 518.

- Cichopek-Gajraj 2014, p. 61.

- Bazyler et al. 2019, p. 402.

- Cichopek-Gajraj 2014, p. 94.

- Cichopek-Gajraj 2014, pp. 104–105, 111–112, 118–119, 127–129.

- Paulovičová 2013, pp. 556–557.

- Cichopek-Gajraj 2014, p. 117.

- Paulovičová 2018, p. 15.

- Šindelářová 2013b, p. 597.

- Bauer 1994, p. 91.

- Ward 2013, p. 265.

- Ward 2013, p. 262.

- Fedorčák 2015, p. 42.

- Ward 2013, pp. 258, 263.

- Fedorčák 2015, p. 41.

- Fedorčák 2015, p. 44.

- Lônčíková 2017, p. 86.

- Láníček 2013, p. 51.

- Cichopek-Gajraj 2014, pp. 165–166, 169.

- Cichopek-Gajraj 2014, pp. 228–230.

- Paulovičová 2018, p. 17.

- Sniegon 2014, p. 61.

- Paulovičová 2018, pp. 15–16.

- Sniegon 2014, pp. 58, 62.

- Paulovičová 2013, p. 558.

- Sniegon 2014, p. 67.

- Ward 2013, p. 269.

- Sniegon 2014, pp. 69–70.

- Kubátová & Láníček 2018, pp. 217–218.

- Sniegon 2014, pp. 73, 84–85, 166.

- Paulovičová 2013, p. 574.

- Sniegon 2014, pp. 89–90.

- Paulovičová 2013, p. 575.

- Paulovičová 2013, pp. 564–565.

- Bazyler et al. 2019, pp. 401–402.

- Bazyler et al. 2019, p. 411.

- Yad Vashem 2019.

- Subotić 2019, p. 211.

- Paulovičová 2013, pp. 566–567.

- Ward 2013, p. 277.

- Sniegon 2014, p. 209.

- Ward 2013, pp. 276, 278.

- Kubátová & Láníček 2017, p. 3.

- Spectator 2019.

- Paulovičová 2018, pp. 17, 20.

- Spectator 2016.

- Spectator 2017.

Books

- Aronson, Shlomo (2004). Hitler, the Allies, and the Jews. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-511-51183-7.

- Bauer, Yehuda (1994). Jews for Sale?: Nazi-Jewish Negotiations, 1933–1945. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-05913-7.

- Bauer, Yehuda (2002). Rethinking the Holocaust. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-09300-1.

- Cichopek-Gajraj, Anna (2014). Beyond Violence: Jewish Survivors in Poland and Slovakia, 1944–48. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-03666-6.

- Dojc, Yuri; Krausová, Katya (2011). Last Folio: Textures of Jewish Life in Slovakia. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-22377-7.

- Fatran, Gila (2007). Boj o prežitie [The Struggle for Survival] (in Slovak). Bratislava: Múzeum Židovskej Kultúry. ISBN 978-80-8060-206-2.

- Foreign Claims Settlement Commission (1968). Foreign Claims Settlement Commission of the United States: Decisions and Annotations. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. OCLC 1041397012.

- Hilberg, Raul (2003) [1961]. The Destruction of the European Jews. Vol. 2 (3 ed.). New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-09592-0.

- Kamenec, Ivan (2007) [1991]. On the Trail of Tragedy: The Holocaust in Slovakia. Translated by Styan, Martin. Bratislava: Hajko & Hajková. ISBN 978-80-88700-68-5.

- Klein-Pejšová, Rebekah (2015). Mapping Jewish Loyalties in Interwar Slovakia. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-01562-4.

- Kornberg, Jacques (2015). The Pope's Dilemma: Pius XII Faces Atrocities and Genocide in the Second World War. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1-4426-2828-1.

- Kubátová, Hana; Láníček, Jan (2018). The Jew in Czech and Slovak Imagination, 1938–89: Antisemitism, the Holocaust, and Zionism. Leiden, Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-36244-4.

- Láníček, Jan (2013). Czechs, Slovaks and the Jews, 1938–48: Beyond Idealisation and Condemnation. New York: Springer. ISBN 978-1-137-31747-6.

- Longerich, Peter (2010). Holocaust: The Nazi Persecution and Murder of the Jews. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280436-5.

- Lorman, Thomas (2019). The Making of the Slovak People's Party: Religion, Nationalism and the Culture War in Early 20th-Century Europe. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-350-10938-4.

- Silberklang, David (2013). Gates of Tears: the Holocaust in the Lublin District. Jerusalem: Yad Vashem. ISBN 978-965-308-464-3.

- Šindelářová, Lenka (2013). Finale der Vernichtung: die Einsatzgruppe H in der Slowakei 1944/1945 (in German). Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft. ISBN 978-3-534-73733-8.

- Sniegon, Tomas (2014). Vanished History: The Holocaust in Czech and Slovak Historical Culture. New York: Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-1-78238-294-2.

- Sokolovič, Peter (2009). Hlinkova Garda 1938–1945 [Hlinka Guard 1938–1945] (PDF) (in Slovak). Bratislava: National Memory Institute. ISBN 978-80-89335-10-7.

- Subotić, Jelena (2019). Yellow Star, Red Star: Holocaust Remembrance After Communism. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-1-5017-4240-8.

- Ward, James Mace (2013). Priest, Politician, Collaborator: Jozef Tiso and the Making of Fascist Slovakia. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-6812-4.

Book chapters

- Bazyler, Michael J.; Boyd, Kathryn Lee; Nelson, Kristen L.; Shah, Rajika L. (2019). "Slovakia". Searching for Justice after the Holocaust: Fulfilling the Terezin Declaration and Immovable Property Restitution. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 401–413. ISBN 978-0-19-092306-8.

- Bloxham, Donald (2017). "The Murder of European Jewry: Nazi Genocide in Continental Perspective". In Pendas, Devin O.; Roseman, Mark; Wetzell, Richard F. (eds.). Beyond the Racial State: Rethinking Nazi Germany. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-316-73286-1.

- Dreyfus, Jean-Marc; Nižňanský, Eduard (2011). "Jews and non-Jews in the Aryanization Process: Comparison of France and the Slovak State, 1939–45". In Kosmala, Beate; Verbeeck, Georgi (eds.). Facing the Catastrophe: Jews and non-Jews in Europe during World War II. Oxford: Berg. ISBN 978-1-84520-471-6.

- Fatran, Gila (2002) [1992]. "The Struggle for Jewish Survival during the Holocaust". In Długoborski, Wacław; Tóth, Dezider; Teresa, Świebocka; Mensfelt, Jarek (eds.). The Tragedy of the Jews of Slovakia 1938–1945: Slovakia and the "Final Solution of the Jewish Question". Translated by Mensfeld, Jarek. Oświęcim and Banská Bystrica: Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum and Museum of the Slovak National Uprising. pp. 141–162. ISBN 978-83-88526-15-2.

- Hradská, Katarína (2016). "Dislokácie Židov z Bratislavy na jeseň 1941" [The Displacement of Jews from Bratislava in Autumn 1941]. In Roguľová, Jaroslava; Hertel, Maroš (eds.). Adepti Moci a úspechu. Etablovanie Elít V Moderných Dejinách [Candidates for Power and Success. Formation of Elites in Modern History] (PDF) (in Slovak). Bratislava: Forum Historiae (Slovak Academy of Sciences). pp. 315–324. ISBN 978-80-224-1503-3.

- Hutzelmann, Barbara (2016). "Slovak Society and the Jews: Attitudes and Patterns of Behaviour". In Bajohr, Frank; Löw, Andrea (eds.). The Holocaust and European Societies: Social Processes and Social Dynamics. London: Springer. pp. 167–185. ISBN 978-1-137-56984-4.

- Hutzelmann, Barbara (2018). "Einführung: Slowakei" [Introduction: Slovakia]. In Hutzelmann, Barbara; Hausleitner, Mariana; Hazan, Souzana (eds.). Slowakei, Rumänien und Bulgarien [Slovakia, Romania, and Bulgaria]. Die Verfolgung und Ermordung der europäischen Juden durch das nationalsozialistische Deutschland 1933–1945 [The Persecution and Murder of European Jews by Nazi Germany 1933–1945] (in German). Vol. 13. Munich: De Gruyter. pp. 18–45. ISBN 978-3-11-049520-1.

- Kamenec, Ivan (2011). "The Slovak state, 1939–1945". In Teich, Mikuláš; Kováč, Dušan; Brown, Martin D. (eds.). Slovakia in History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 175–192. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511780141. ISBN 978-1-139-49494-6.

- Kubátová, Hana (2014). "Jewish Resistance in Slovakia, 1938–1945". In Henry, Patrick (ed.). Jewish Resistance Against the Nazis. Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press. pp. 504–518. ISBN 978-0-8132-2589-0.

- Paulovičová, Nina (2013). "The "Unmasterable Past"? The Reception of the Holocaust in Postcommunist Slovakia". In Himka, John-Paul; Michlic, Joanna Beata (eds.). Bringing the Dark Past to Light. The Reception of the Holocaust in Postcommunist Europe. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. pp. 549–590. ISBN 978-0-8032-2544-2.

- Rothkirchen, Livia (2001). "Slovakia". In Laqueur, Walter; Baumel, Judith Tydor (eds.). Holocaust Encyclopedia. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 595–600. ISBN 978-0-300-08432-0.

- Tönsmeyer, Tatjana (2007). "The Robbery of Jewish Property in Eastern European States Allied with Nazi Germany". In Dean, Martin; Goschler, Constantin; Ther, Philipp (eds.). Robbery and Restitution: The Conflict over Jewish Property in Europe. New York: Berghahn Books. pp. 81–96. ISBN 978-0857455642.

Book reviews

- Cichopek-Gajraj, Anna (2018). "Nepokradeš! Nálady a postoje slovenské společnosti k židovské otázce, 1938–1945 [Thou shall not steal! Moods and attitudes of Slovak society toward the Jewish question]". East European Jewish Affairs. 48 (2): 253–255. doi:10.1080/13501674.2018.1505360. S2CID 165456557.

- Johnson, Owen V. (2005). "Židovská komunita na Slovensku medzi ceskoslovenskou parlamentnou demokraciou a slovenským štátom v stredoeurópskom kontexte, Eduard Nižnanský (Prešov, Slovakia: Universum, 1999), 292 pp., 200 crowns (Slovak)". Holocaust and Genocide Studies. 19 (2): 314–317. doi:10.1093/hgs/dci033.

Theses

- Borský, Maroš (2005). Synagogue Architecture in Slovakia Towards Creating a Memorial Landscape of Lost Community (PDF) (PhD thesis). Center for Jewish Studies Heidelberg.

- Paulovičová, Nina (2012). Himka, John-Paul (ed.). Rescue of Jews in the Slovak State (1939–1945) (PhD thesis). Edmonton: University of Alberta. doi:10.7939/R33H33.

- Putík, Daniel (2015). Slovenští Židé v Terezíně, Sachsenhausenu, Ravensbrücku a Bergen-Belsenu, 1944/1945 [Slovak Jews in Theresienstadt, Sachsenhausen, Ravensbrück and Bergen-Belsen, 1944/1945] (PhD thesis) (in Czech). Prague: Charles University.

Journal articles

- Büchler, Yehoshua (1991). "The deportation of Slovakian Jews to the Lublin District of Poland in 1942". Holocaust and Genocide Studies. 6 (2): 151–166. doi:10.1093/hgs/6.2.151. ISSN 8756-6583.

- Büchler, Yehoshua (1996). "First in the Vale of Affliction: Slovakian Jewish Women in Auschwitz, 1942". Holocaust and Genocide Studies. 10 (3): 299–325. doi:10.1093/hgs/10.3.299. ISSN 8756-6583.

- Fatran, Gila (1994). Translated by Greenwood, Naftali. "The "Working Group"". Holocaust and Genocide Studies. 8 (2): 164–201. doi:10.1093/hgs/8.2.164. ISSN 8756-6583.

- Fatran, Gila (1996). "Die Deportation der Juden aus der Slowakei 1944–1945" [The deportation of the Jews from Slovakia 1944–45]. Bohemia: Zeitschrift für Geschichte und Kultur der Böhmischen Länder (in German). 37 (37): 98–119. ISSN 0523-8587.

- Fedorčák, Peter (2015). "Proces s Vojtechom Tukom v roku 1946" [The trial of Vojtech Tuka in 1946]. Človek a Spoločnosť (in Slovak). 18 (4): 41–52. ISSN 1335-3608.

- Frankl, Michal (2019). "Země nikoho 1938. Deportace za hranice občanství" [No Man’s Land in 1938. Deportation beyond the Bounds of Citizenship]. Forum Historiae (in Slovak). 13 (1): 92–115. doi:10.31577/forhist.2019.13.1.7.

- Hallon, Ľudovít (2007). "Arizácia na Slovensku 1939–1945" [Aryanization in Slovakia 1939–1945] (PDF). Acta Oeconomica Pragensia (in Czech). 15 (7): 148–160. doi:10.18267/j.aop.187. ISSN 1804-2112.

- Kamenec, Ivan (2011). "Fenomén korupcie v procese tzv. riešenia "židovskej otázky" na Slovensku v rokoch 1938–1945" [The phenomenon of corruption in the so-called solutions to the "Jewish questions" in Slovakia between 1938 and 1945]. Forum Historiae (in Slovak). 5 (2): 96–112. ISSN 1337-6861.