Assyrian siege of Jerusalem

The Assyrian siege of Jerusalem (circa 701 BCE) was an aborted siege of Jerusalem, then capital of the Kingdom of Judah, carried out by Sennacherib, king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. The siege concluded Sennacharib's campaign in the Levant, in which he attacked the fortified cities and devastated the countryside of Judah in a campaign of subjugation. Sennacherib besieged Jerusalem, but did not capture it.

| Siege of Jerusalem | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Sennacherib's campaign in the Levant | |||||||

Hezekiah's Wall | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Sennacherib's Rabshakeh Sennacherib's Rabsaris Sennacherib's Tartan |

King Hizkiyahu of Judah Eliakim ben Hilkiyahu Yoah ben Asaf Shebna | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

Unknown

| Unknown | ||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Jerusalem |

|---|

|

Sennacherib's Annals describe how the king trapped Hezekiah of Judah in Jerusalem "like a caged bird" and later returned to Assyria when he received tribute from Judah. In the Hebrew Bible, Hezekiah is described as paying 300 talents of silver and 30 talents of gold to Assyria. The biblical story then adds a miraculous ending in which Sennacherib marches on Jerusalem with his army only to have it struck down near the gates of Jerusalem by an angel, prompting his retreat to Nineveh.

According to biblical archaeological theory, Siloam tunnel and the Broad Wall in Jerusalem were built by Hezekiah in preparation for the impending siege.

Background

In 720 BCE, the Assyrian army captured Samaria, the capital of the northern Kingdom of Israel, and carried away many Israelites into captivity. The virtual destruction of Israel left the southern kingdom, Judah, to fend for itself among warring Near-Eastern kingdoms. After the fall of the northern kingdom, the kings of Judah tried to extend their influence and protection to those inhabitants who had not been exiled. They also sought to extend their authority northward into areas previously controlled by the Kingdom of Israel. The latter part of the reigns of King Ahaz and King Hezekiah were periods of stability during which Judah was able to consolidate both politically and economically. Although Judah was a vassal of Assyria during this time and paid an annual tribute to the powerful empire, it was the most important state between Assyria and Egypt.[1]

When Hezekiah became king of Judah, he initiated widespread religious changes, including the breaking of religious idols. He re-captured Philistine-occupied lands in the Negev desert, formed alliances with Ashkelon and Egypt, and made a stand against Assyria by refusing to pay tribute.[2] In response, Sennacherib attacked Judah, laying siege to Jerusalem.

The siege

Sources from both sides claimed victory, the Judahites (or biblical authors) in the Tanakh, and Sennacherib in his prism. Sennacherib claimed the siege and capture of many Judaean cities, but only the siege—not capture—of Jerusalem.

Hebrew account

The story of the Assyrian siege is told in the biblical books of Isaiah (7th century BCE), Second Kings (mid-6th century BCE) and Chronicles (c. 350–300 BCE). As the Assyrians began their invasion, King Hezekiah began preparations to protect Jerusalem. In an effort to deprive the Assyrians of water, springs outside the city were blocked. Workers then dug a 533-meter tunnel to the Spring of Gihon, providing the city with fresh water. Additional siege preparations included fortification of the existing walls, construction of towers, and the erection of a new reinforcing wall. Hezekiah gathered the citizens in the square and encouraged them by reminding them that the Assyrians possessed only "an arm of flesh", but the Judeans had the protection of Yahweh.

According to 2 Kings 18, while Sennacherib was besieging Lachish, he received a message from Hezekiah offering to pay tribute in exchange for Assyrian withdrawal. According to the Hebrew Bible, Hezekiah paid 300 talents of silver and 30 talents of gold to Assyria—a price so heavy that he was forced to empty the temple and royal treasury of silver and strip the gold from the doorposts of Solomon's Temple. Nevertheless, Sennacherib marched on Jerusalem with a large army. When the Assyrian force arrived, its field commander Rabshakeh brought a message from Sennacherib. In an attempt to demoralize the Judeans, the field commander announced to the people on the city walls that Hezekiah was deceiving them, and that Yahweh could not deliver Jerusalem from the king of Assyria. He listed the gods of other peoples defeated by Sennacherib then asked, "Who of all the gods of these countries has been able to save his land from me?"

During the siege, Hezekiah dressed in sackcloth (a sign of mourning), but the prophet Isaiah assured him that the city would be delivered and Sennacherib would fail.[1] According to Isaiah, an angel then killed 185,000 Assyrian troops overnight.[2] Some scholars believe this number has been transcribed incorrectly, with one study suggesting the number was originally 5,180.[3] Another scholar advises that the biblical narrative is marked by legendary embellishments that end with a miracle that saves Jerusalem.[4]

While Isaiah 36-37 and 2 Kings 18:13-19:37 emphasize the intervention of Yahweh in saving Jerusalem, other biblical texts reveal the horrors inflicted on Judeans outside of Jerusalem during the Assyrian campaign and the devastation wrought on towns and villages throughout the Judean countryside. The territory of the Kingdom of Judah was scaled back by Sennacherib, and a significant number of Judeans were deported to Assyria. The Assyrian king achieved his goals: he broke the resistance of Judah and subjugated it.[5]

Assyrian account

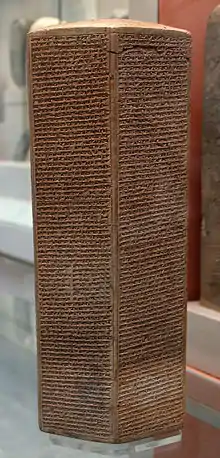

Sennacherib's Prism, which details the events of Sennacherib's campaign against Judah, was discovered in the ruins of Nineveh in 1830, and is now stored at the Oriental Institute in Chicago, Illinois.[2] The account dates from about 690 BCE. The text of the prism boasts how Sennacherib destroyed 46 of Judah's cities and trapped Hezekiah in Jerusalem "like a caged bird." The text goes on to describe how the "terrifying splendor" of the Assyrian army caused the Arabs and mercenaries reinforcing the city to desert. It adds that the Assyrian king returned to Assyria where he later received a large tribute from Judah. This description inevitably varies somewhat from the Jewish version in the Tanakh. The massive Assyrian casualties mentioned in the Tanakh are not mentioned in the Assyrian version.

After he besieged Jerusalem, Sennacherib was able to give the surrounding towns to Assyrian vassal rulers in Ekron, Gaza and Ashdod. His army still existed when he conducted campaigns in 702 BCE and from 699 BCE until 697 BCE, when he made several campaigns in the mountains east of Assyria, during one of which he received tribute from the Medes. In 696 BCE and 695 BCE, he sent expeditions into Anatolia, where several vassals had rebelled following the death of Sargon II. Around 690 BCE, he campaigned in the northern Arabian deserts, conquering Dumat al-Jandal, where the queen of the Arabs had taken refuge.[6]

Other theories

Herodotus wrote that the Assyrian army was overrun by mice when attacking Egypt.[7] Some Biblical scholars take this to an allusion that the Assyrian army suffered the effects of a mouse- or rat-borne disease such as bubonic plague.[3][8] Even without relying on that explanation, John Bright suggested it was an epidemic of some kind that saved Jerusalem.[3] The Babylonian historian Berossus also wrote that it was a plague that defeated the Assyrian army in the siege.[9]

Henry T. Aubin writes in The Rescue of Jerusalem: The Alliance Between Hebrews and Africans in 701 B.C.[10] that the Assyrian army was routed by an Egyptian army under Kushite (Nubian) command. However, recent extensive archaeological analysis has shown that Aubin's Egyptian hypothesis is unlikely.[11]

In popular culture

An 1813 poem by Lord Byron, The Destruction of Sennacherib, commemorates Sennacherib's campaign in Judea from the Hebrew point of view. Written in anapestic tetrameter, the poem was popular in school recitations.

Ancient sources

See also

References

- Malamat, Abraham and Ben-Sasson, Haim Hillel. A History of the Jewish People, Harvard University Press, 1976 ISBN 9780674397316

- "Pritchard, James B. ed., Ancient Near Eastern Texts, 2nd ed. (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1955), 287ff". Archived from the original on 2014-10-06. Retrieved 2013-07-15.

- "A History of Israel", John Bright, SCM 1980, p.200

- Lemche, Niels Peter (2008). The Old Testament between Theology and History. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-664-23245-0.

- Finkelstein, Israel and Neil Asher Silberman (2002). The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts. Touchstone. pp. 263–264. ISBN 978-0-684-86913-1.

- Grayson 1991, p. 111-113.

- The History Of Herodotus, Book 2, Verse 141

- "Sennachrib", New Bible Dictionary, InterVarsity Press, 2nd Edition, Ed. J.D.Douglas, N.Hillyer, 1982

- Flavius Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, Book 10, chapter 1, section 5

- Aubin, Henry (2002). The rescue of Jerusalem : the alliance between Hebrews and Africans in 701 BC. Toronto: Doubleday Canada. ISBN 9780385659123.

- Nazek Khalid Matty (2016), Sennacherib's Campaign Against Judah and Jerusalem in 701 BC; pp. 178-180; De Gryuter, Berlin/Boston

Sources

- Finkelstein, Israel and Neil Asher Silberman (2002). The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of its Sacred Texts. Touchstone. ISBN 9780684869131.

- Grabbe, Lester (2003). Like a Bird in a Cage: The Invasion of Sennacherib in 701 BCE. A&C Black. ISBN 9780826462152.

- Grayson, A.K. (1991). "Assyria: Sennacherib and Essarhaddon". In Boardman, John; Edwards, I. E. S. (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume III Part II. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521227179.

- Lemche, Niels Peter (2008). The Old Testament between Theology and History. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-23245-0.