Astoria, Oregon

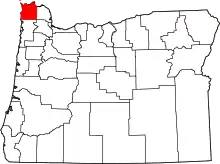

Astoria is a port city and the seat of Clatsop County, Oregon, United States. Founded in 1811, Astoria is the oldest city in the state and was the first permanent American settlement west of the Rocky Mountains.[6] The county is the northwest corner of Oregon, and Astoria is located on the south shore of the Columbia River, where the river flows into the Pacific Ocean. The city is named for John Jacob Astor, an investor and entrepreneur from New York City, whose American Fur Company founded Fort Astoria at the site and established a monopoly in the fur trade in the early 19th century. Astoria was incorporated by the Oregon Legislative Assembly on October 20, 1856.[1]

Astoria | |

|---|---|

View of Astoria and Astoria–Megler Bridge The replica of Fort Astoria | |

Seal | |

| Coordinates: 46°11′20″N 123°49′16″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Oregon |

| County | Clatsop |

| Founded | 1811 |

| Incorporated | 1876[1] |

| Named for | John Jacob Astor |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Sean Fitzpatrick |

| Area | |

| • Total | 9.95 sq mi (25.77 km2) |

| • Land | 6.11 sq mi (15.82 km2) |

| • Water | 3.84 sq mi (9.95 km2) |

| Elevation | 23 ft (7 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 10,181 |

| • Density | 1,666.56/sq mi (643.42/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−08:00 (PST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−07:00 (PDT) |

| ZIP Code | 97103 |

| Area codes | 503 and 971 |

| FIPS code | 41-03150[4] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1117076[5] |

| Website | www.astoria.or.us |

The city is served by the deepwater Port of Astoria. Transportation includes the Astoria Regional Airport. U.S. Route 30 and U.S. Route 101 are the main highways, and the 4.1-mile (6.6 km) Astoria–Megler Bridge connects to neighboring Washington across the river. The population was 10,181 at the 2020 census.[7]

History

Prehistoric settlements

During archeological excavations in Astoria and Fort Clatsop in 2012, trading items from American settlers with Native Americans were found, including Austrian glass beads and falconry bells. The present area of Astoria belonged to a large, prehistoric Native American trade system of the Columbia Plateau.[8][9]

19th century

The Lewis and Clark Expedition spent the winter of 1805–1806 at Fort Clatsop, a small log structure southwest of modern-day Astoria. The expedition had hoped a ship would come by that could take them back east, but instead, they endured a torturous winter of rain and cold. They later returned overland and by internal rivers, the way they had traveled west.[10] Today, the fort has been recreated and is part of Lewis and Clark National Historical Park.[11]

In 1811, British explorer David Thompson, the first person known to have navigated the entire length of the Columbia River, reached the partially constructed Fort Astoria near the mouth of the river. He arrived two months after the Pacific Fur Company's ship, the Tonquin.[12] The fort constructed by the Tonquin party established Astoria as a U.S., rather than a British, settlement[12] and became a vital post for American exploration of the continent. It was later used as an American claim in the Oregon boundary dispute with European nations.

The Pacific Fur Company, a subsidiary of John Jacob Astor's American Fur Company, was created to begin fur trading in the Oregon Country.[13] During the War of 1812, in 1813, the company's officers sold its assets to their Canadian rivals, the North West Company, which renamed the site Fort George. The fur trade remained under British control until U.S. pioneers following the Oregon Trail began filtering into the town in the mid-1840s. The Treaty of 1818 established joint U.S. – British occupancy of the Oregon Country.[14][15]

Washington Irving, a prominent American writer with a European reputation, was approached by John Jacob Astor to mythologize the three-year reign of his Pacific Fur Company. Astoria (1835), written while Irving was Astor's guest, promoted the importance of the region in the American psyche.[16] In Irving's words, the fur traders were "Sinbads of the wilderness", and their venture was a staging point for the spread of American economic power into both the continental interior and outward in Pacific trade.[17]

In 1846, the Oregon Treaty divided the mainland at the 49th parallel north, making Astoria officially part of the United States.[18] As the Oregon Territory grew and became increasingly more colonized by Americans, Astoria likewise grew as a port city near the mouth of the great river that provided the easiest access to the interior. The first U.S. post office west of the Rocky Mountains was established in Astoria in 1847[19] and official state incorporation in 1876.[1]

Astoria attracted a host of immigrants beginning in the late 19th century: Nordic settlers, primarily Swedes, Swedish speaking Finns, and Chinese soon became larger parts of the population. The Nordic settlers mostly lived in Uniontown, near the present-day end of the Astoria–Megler Bridge, and took fishing jobs; the Chinese tended to do cannery work, and usually lived either downtown or in bunkhouses near the canneries. By the late 1800s, 22% of Astoria's population was Chinese.[20][21][22] Astoria also had a significant population of Indians, especially Sikhs from Punjab; the Ghadar Party, a political movement among Indians on the West Coast of the U.S. and Canada to overthrow British rule in India, was officially founded on July 15, 1913, in Astoria.[23]

20th and 21st centuries

In 1883, and again in 1922, downtown Astoria was devastated by fire, partly because the buildings were constructed mostly of wood, a readily available material. The buildings were entirely raised off the marshy ground on wooden pilings. Even after the first fire, the same building format was used. In the second fire, flames spread quickly again, and the collapsing streets took out the water system. Frantic citizens resorted to dynamite, blowing up entire buildings to create fire stops.[24][25]

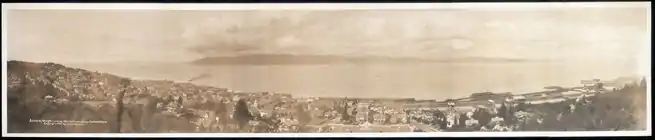

| Panoramic views of Astoria in the early 20th century |

|---|

Astoria has served as a port of entry for over a century and remains the trading center for the lower Columbia basin. In the early 1900s, the Callendar Navigation Company was an important transportation and maritime concern based in the city.[26] It has long since been eclipsed in importance by Portland, Oregon, and Seattle, Washington, as economic hubs on the coast of the Pacific Northwest. Astoria's economy centered on fishing, fish processing, and lumber. In 1945, about 30 canneries could be found along the Columbia River.

In the early 20th century, the North Pacific Brewing Company contributed substantially to the economic well-being of the town.[27] Before 1902, the company was owned by John Kopp, who sold the firm to a group of five men, one of whom was Charles Robinson, who became the company's president in 1907.[28][29] The main plant for the brewery was located on East Exchange Street.[30]

As the Pacific salmon resource diminished, canneries were closed. In 1974, the Bumble Bee Seafoods corporation moved its headquarters out of Astoria and gradually reduced its presence until closing its last Astoria cannery in 1980.[31] The lumber industry likewise declined in the late 20th century. Astoria Plywood Mill, the city's largest employer, closed in 1989. The Burlington Northern and Santa Fe Railway discontinued service to Astoria in 1996, as it did not provide a large enough market.[32]

From 1921 to 1966, a ferry route across the Columbia River connected Astoria with Pacific County, Washington. In 1966, the Astoria–Megler Bridge was opened. The bridge completed U.S. Route 101 and linked Astoria with Washington on the opposite shore of the Columbia, replacing the ferry service.[33]

Today, tourism, Astoria's growing art scene, and light manufacturing are the main economic activities of the city. Logging and fishing persist, but at a fraction of their former levels.[34] Since 1982 it has been a port of call for cruise ships, after the city and port authority spent $10 million in pier improvements to accommodate these larger ships.

To avoid Mexican ports of call during the swine flu outbreak of 2009, many cruises were rerouted to include Astoria. The floating residential community MS The World visited Astoria in June 2009.[35]

The town's seasonal sport fishing tourism has been active for several decades.[36][37][38] Visitors attracted by heritage tourism and the historic elements of the city have supplanted fishing in the economy. Since the early 21st century, the microbrewery/brewpub scene[39] and a weekly street market[40] have helped popularize the area as a destination.

In addition to the replicated Fort Clatsop, another point of interest is the Astoria Column, a tower 125 feet (38 m) high, built atop Coxcomb Hill above the town. Its inner circular staircase allows visitors to climb to see a panoramic view of the town, the surrounding lands, and the Columbia flowing into the Pacific. The tower was built in 1926. Financing was provided by the Great Northern Railway, seeking to encourage tourists, and Vincent Astor, a great-grandson of John Jacob Astor, in commemoration of the city's role in the family's business history and the region's early history.[41][42]

Since 1998, artistically inclined fishermen and women from Alaska and the Pacific Northwest have traveled to Astoria for the Fisher Poets Gathering, where poets and singers tell their tales to honor the fishing industry and lifestyle.[43]

Another popular annual event is the Dark Arts Festival, which features music, art, dance, and demonstrations of craft such as blacksmithing and glassblowing, in combination with offerings of a large array of dark craft brews. Dark Arts Festival began as a small gathering at a community arts space. Now Fort George Brewery hosts the event, which draws hundreds of visitors and tour buses from Seattle.[44]

Astoria is the western terminus of the TransAmerica Bicycle Trail, a 4,250-mile (6,840 km) coast-to-coast bicycle touring route created in 1976 by the Adventure Cycling Association.[45]

Three United States Coast Guard cutters: the Steadfast, Alert, and Elm, are homeported in Astoria.[46]

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 10.11 square miles (26.18 km2), of which 3.95 square miles (10.23 km2) are covered by water.[47]

Climate

_-_Astoria_Area%252C_OR(ThreadEx).svg.png.webp)

Astoria lies within the Mediterranean climate zone (Köppen Csb), with cool winters and mild summers, although short heat waves can occur. Rainfall is most abundant in late fall and winter and is lightest in July and August, averaging about 67 inches (1,700 mm) of rain each year.[48] Snowfall is relatively rare, averaging under 5 inches (13 cm) a year and frequently having none.[49] Nevertheless, when conditions are ripe, significant snowfalls can occur.

Astoria's monthly average humidity is always over 80% throughout the year, with average monthly humidity reaching a high of 84% from November to March, with a low of 81% during May.[50] The average relative humidity in Astoria is 89% in the morning and 73% in the afternoon.[51]

Annually, an average of only 4.2 afternoons have temperatures reaching 80 °F (26.7 °C) or higher, and 90 °F or 32.2 °C readings are rare. Normally, only one or two nights per year occur when the temperature remains at or above 60 °F or 15.6 °C.[52] An average of 31 mornings have minimum temperatures at or below the freezing mark. The record high temperature was 101 °F (38.3 °C) on July 1, 1942, and June 27, 2021. The record low temperature was 6 °F (−14.4 °C) on December 8, 1972, and on December 21, 1990. Even with such a cold record low, afternoons usually remain mild in winter. On average, the coldest daytime high is 36 °F (2 °C) whereas the lowest daytime maximum on record is 19 °F (−7 °C).[53] Even during brief heat spikes, nights remain cool. The warmest overnight low is 63 °F (17 °C) set as early in the year as in May during 2008.[53] Nights close to that record are common with the normally warmest night of the year being at 61 °F (16 °C).[53]

On average, 191 days have measurable precipitation. The wettest "water year", defined as October 1 through September 30 of the next year, was from 1915 to 1916 with 108.04 in (2,744 mm) and the driest from 2000 to 2001 with 44.50 in (1,130 mm). The most rainfall in one month was 36.07 inches (916.2 mm) in December 1933, and the most in 24 hours was 5.56 inches (141.2 mm) on November 25, 1998.[53] The most snowfall in one month was 26.9 in (68 cm) in January 1950,[54][55] and the most snow in 24 hours was 12.5 in (32 cm) on December 11, 1922.[53]

| Climate data for Astoria Regional Airport (1991–2020 normals,[lower-alpha 1] extremes 1892–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 70 (21) |

72 (22) |

80 (27) |

85 (29) |

93 (34) |

101 (38) |

101 (38) |

98 (37) |

95 (35) |

85 (29) |

73 (23) |

64 (18) |

101 (38) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 58.9 (14.9) |

61.4 (16.3) |

65.5 (18.6) |

71.9 (22.2) |

77.8 (25.4) |

79.1 (26.2) |

81.7 (27.6) |

83.7 (28.7) |

81.9 (27.7) |

74.1 (23.4) |

62.8 (17.1) |

57.9 (14.4) |

89.4 (31.9) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 49.4 (9.7) |

50.9 (10.5) |

53.0 (11.7) |

55.9 (13.3) |

60.5 (15.8) |

64.0 (17.8) |

67.4 (19.7) |

68.7 (20.4) |

67.6 (19.8) |

60.7 (15.9) |

53.6 (12.0) |

48.7 (9.3) |

58.4 (14.7) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 43.7 (6.5) |

44.2 (6.8) |

46.0 (7.8) |

48.7 (9.3) |

53.4 (11.9) |

57.3 (14.1) |

60.6 (15.9) |

61.3 (16.3) |

59.0 (15.0) |

52.8 (11.6) |

46.9 (8.3) |

43.2 (6.2) |

51.4 (10.8) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 38.1 (3.4) |

37.4 (3.0) |

39.0 (3.9) |

41.5 (5.3) |

46.3 (7.9) |

50.6 (10.3) |

53.9 (12.2) |

53.9 (12.2) |

50.5 (10.3) |

44.9 (7.2) |

40.2 (4.6) |

37.6 (3.1) |

44.5 (6.9) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 27.2 (−2.7) |

26.7 (−2.9) |

29.6 (−1.3) |

33.3 (0.7) |

37.6 (3.1) |

43.0 (6.1) |

46.9 (8.3) |

46.7 (8.2) |

41.8 (5.4) |

34.1 (1.2) |

29.3 (−1.5) |

26.8 (−2.9) |

22.6 (−5.2) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 11 (−12) |

9 (−13) |

22 (−6) |

26 (−3) |

30 (−1) |

37 (3) |

37 (3) |

39 (4) |

33 (1) |

26 (−3) |

15 (−9) |

6 (−14) |

6 (−14) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 10.59 (269) |

7.18 (182) |

7.90 (201) |

5.80 (147) |

3.40 (86) |

2.30 (58) |

0.83 (21) |

1.12 (28) |

2.67 (68) |

6.74 (171) |

11.05 (281) |

10.68 (271) |

70.26 (1,785) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 0.4 (1.0) |

0.5 (1.3) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.3 (0.76) |

0.2 (0.51) |

1.4 (3.6) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 21.6 | 18.8 | 21.5 | 19.2 | 15.5 | 13.7 | 8.1 | 7.7 | 10.1 | 16.6 | 21.1 | 22.0 | 195.9 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 1.7 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 82.7 | 82.2 | 80.9 | 79.5 | 79.5 | 79.8 | 79.8 | 81.6 | 81.1 | 82.9 | 83.3 | 84.0 | 81.4 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 36.7 (2.6) |

38.7 (3.7) |

39.4 (4.1) |

41.4 (5.2) |

45.9 (7.7) |

50.2 (10.1) |

53.1 (11.7) |

54.1 (12.3) |

51.8 (11.0) |

47.1 (8.4) |

41.9 (5.5) |

37.8 (3.2) |

44.8 (7.1) |

| Source: NOAA (relative humidity and dew point 1961–1990, snowfall & snow days 1981–2010)[53][56][57][58] | |||||||||||||

Notes

- Mean monthly maxima and minima (i.e. the highest and lowest temperature readings during an entire month or year) calculated based on data at said location from 1991 to 2020.

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1860 | 252 | — | |

| 1870 | 639 | 153.6% | |

| 1880 | 2,803 | 338.7% | |

| 1890 | 6,184 | 120.6% | |

| 1900 | 8,351 | 35.0% | |

| 1910 | 9,599 | 14.9% | |

| 1920 | 14,027 | 46.1% | |

| 1930 | 10,349 | −26.2% | |

| 1940 | 10,389 | 0.4% | |

| 1950 | 12,331 | 18.7% | |

| 1960 | 11,239 | −8.9% | |

| 1970 | 10,244 | −8.9% | |

| 1980 | 9,998 | −2.4% | |

| 1990 | 10,069 | 0.7% | |

| 2000 | 9,813 | −2.5% | |

| 2010 | 9,477 | −3.4% | |

| 2020 | 10,181 | 7.4% | |

| Sources:[59][60][61][3] | |||

2010 census

As of the 2010 census,[62] 9,477 people, 4,288 households, and 2,274 families were residing in the city. The population density was 1,538.5 inhabitants per square mile (594.0/km2). The 4,980 housing units had an average density of 808.4 per square mile (312.1/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 89.2% White, 0.6% African American, 1.1% Native American, 1.8% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 3.9% from other races, and 3.3% from two or more races. Hispanics or Latinos of any race were 9.8% of the population.

Of the 4,288 households, 24.6% had children under 18 living with them, 37.9% were married couples living together, 10.8% had a female householder with no husband present, 4.3% had a male householder with no wife present, and 47.0% were not families. About 38.8% of all households were made up of individuals, and 15.1% had someone living alone who was 65 or older. The average household size was 2.15, and the average family size was 2.86.

The median age in the city was 41.9 years; 20.3% of residents were under 18; 8.6% were between 18 and 24; 24.3% were from 25 to 44; 29.9% were from 45 to 64; and 17.1% were 65 or older. The gender makeup of the city was 48.4% male and 51.6% female.

2000 census

As of the 2000 census,[4] 9,813 people, 4,235 households, and 2,469 families resided in the city. The population density was 1,597.6 people per square mile (616.8 people/km2). The 4,858 housing units had an average density of 790.9 per square mile (305.4/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 91.08% White, 0.52% Black or African American, 1.14% Native American, 1.94% Asian, 0.19% Pacific Islander, 2.67% from other races, and 2.46% from two or more races. About 5.98% of the population were Hispanics or Latinos of any race.

By ethnicity, 14.2% were German, 11.4% Irish, 10.2% English, 8.3% United States or American, 6.1% Finnish, 5.6% Norwegian, and 5.4% Scottish according to the 2000 United States Census.

Of the 4,235 households, 28.8% had children under 18 living with them, 43.5% were married couples living together, 11.2% had a female householder with no husband present, and 41.7% were not families. About 35.4% of all households were made up of individuals, and 13.6% had someone living alone who was 65 or older. The average household size was 2.26, and the average family size was 2.93.

In the city the age distribution was 24.0% under 18, 9.1% from 18 to 24, 26.4% from 25 to 44, 24.5% from 45 to 64, and 15.9% were 65 or older. The median age was 38 years. For every 100 females, there were 92.3 males. For every 100 females 18 and over, there were 89.9 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $33,011, and for a family was $41,446. Males had a median income of $29,813 versus $22,121 for females. The per capita income for the city was $18,759. About 11.6% of families and 15.9% of the population were below the poverty line, including 22.0% of those under 18 and 9.6% of those 65 or over.

Government

Astoria operates under a council–manager form of city government. Voters elect four councilors by ward and a mayor, who each serve four-year terms.[63] The mayor and council appoint a city manager to conduct the ordinary business of the city.[63] The current mayor is Sean Fitzpatrick, who took office in January 2023. His predecessor, Bruce Jones, served from 2019 to 2022.

Education

The Astoria School District has four primary and secondary schools, including Astoria High School. Clatsop Community College is the city's two-year college. The city also has a library and many parks with historical significance, plus the second oldest Job Corps facility (Tongue Point Job Corps) in the nation. Tongue Point Job Corps center is the only such location in the country which provides seamanship training.[64]

John Jacob Astor Elementary School

John Jacob Astor Elementary School Astoria High School

Astoria High School_(clatDA0040).jpg.webp) Robert Gray School (Astoria High School Alternative School)

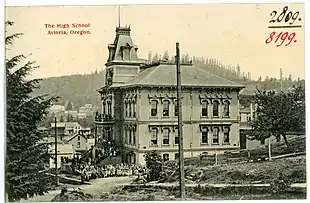

Robert Gray School (Astoria High School Alternative School) The 1906 Astoria High School

The 1906 Astoria High School

Media

The Astorian (formerly The Daily Astorian) is the main newspaper serving Astoria. It was established 151 years ago, in 1873,[65] and has been in continuous publication since that time.[66] The Coast River Business Journal is a monthly business magazine covering Astoria, Clatsop County, and the Northwest Oregon coast. It, along with The Astorian, is part of the EO Media Group (formerly the East Oregonian Publishing Company) family of Oregon and Washington newspapers.[67] The local NPR station is KMUN 91.9, and KAST 1370 is a local news-talk radio station.

In popular culture and entertainment

Actor Clark Gable is claimed to have begun his career at the Astoria Theatre in 1922.[68]

Leroy E. "Ed" Parsons, called the "Father of Cable Television", developed one of the first community antenna television stations (CATV) in the United States in Astoria starting in 1948.[69]

The early 1960s television series Route 66 filmed the episode entitled "One Tiger to a Hill"[70] in Astoria; it was broadcast on September 21, 1962.

Shanghaied in Astoria is a musical about Astoria's history that has been performed in Astoria every year since 1984.[71]

In recent popular culture, Astoria is most famous for being the setting of the 1985 film The Goonies, which was filmed on location in the city. Other notable movies filmed in Astoria include Short Circuit, The Black Stallion, Kindergarten Cop, Free Willy, Free Willy 2: The Adventure Home, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles III, Benji the Hunted, Come See the Paradise, The Ring Two, Into the Wild, The Guardian and Green Room.[72][73][74][75]

A scene in "The Real Thing", episode two of season five (in the 7th year), of the television series Eureka was set in Astoria. The character Jo Lupo parks her vehicle in an unauthorized location while she is meditating on the oceanfront. A tow truck is called to remove the vehicle. A law-enforcement officer whose shoulder clearly displays a patch that reads "Astoria, Oregon" speaks to Jo about the parking violation.

The fourth album of the pop punk band The Ataris was titled So Long, Astoria as an allusion to The Goonies. A song of the same title is the album's first track. The album's back cover features news clippings from Astoria, including a picture of the port's water tower from a 2002 article on its demolition.[76]

The pop punk band Marianas Trench has an album titled Astoria. The band states the album was inspired by 1980s fantasy and adventure films, and The Goonies in particular. That film inspired the title, as it was set in Astoria, the album's artwork, as well as the title of their accompanying US tour (Hey You Guys!!).[77]

Astoria is featured as a city in American Truck Simulator: Oregon.

In the series finale of the TV show Dexter, the title character, Dexter Morgan, ends up in Astoria as the series ends.[78]

Warships named Astoria

Two U.S. Navy cruisers were named USS Astoria: A New Orleans-class heavy cruiser (CA-34) and a Cleveland class light cruiser (CL-90). The former was lost in the Pacific Ocean in combat at the Battle of Savo Island in August 1942, during World War II,[79] and the latter was scrapped in 1971 after being removed from active duty in 1949.[80]

Museums and other points of interest

- Astoria Riverwalk with Astoria Riverfront Trolley, Uniontown Neighborhood, Columbia River Maritime Museum, Uppertown Firefighters Museum and Pier 39 Astoria

- The Astoria Column (the highest point in Astoria) with nearby Cathedral Tree Trail

- Heritage Museum, located in the Old City Hall

- Fort Astoria, Fort George Brewery

- Astor Building, Liberty Theater

- Museum of Whimsy, Astoria Sunday Market, Garden of Surging Waves, Astoria City Hall

- Oregon Film Museum, Flavel House

- Astoria Regional Airport with CGAS Astoria

- Fort Stevens, Clatsop Spit, Fort Clatsop and Youngs River Falls

Sister cities

Astoria has one sister city,[81] as designated by Sister Cities International:

Walldorf, Germany, which is the birthplace of Astoria's namesake, John Jacob Astor, who was born in Walldorf near Heidelberg on July 17, 1763. The sistercityship was founded on Astor's 200th birthday in 1963 in Walldorf by Walldorf's mayor Wilhelm Willinger and Astoria's mayor Harry Steinbock.[82]

Walldorf, Germany, which is the birthplace of Astoria's namesake, John Jacob Astor, who was born in Walldorf near Heidelberg on July 17, 1763. The sistercityship was founded on Astor's 200th birthday in 1963 in Walldorf by Walldorf's mayor Wilhelm Willinger and Astoria's mayor Harry Steinbock.[82]

Notable people

- Bobby Anet, college basketball guard who helped guide the University of Oregon to win the inaugural NCAA Division I men's basketball tournament championship in 1938–1939 attended Astoria High school[83]

- Alexander G. Barry, American attorney Republican member of the Oregon House of Representatives

- Jona Bechtolt, Grammy nominated electronic musician and multimedia artist raised in Astoria

- Del Bjork, a professional American football offensive lineman in the National Football League (NFL). He played two seasons for the Chicago Bears (1937–1938)

- Brian Bruney, Major League Baseball relief pitcher[84]

- Marie Dorion, the only female member of an overland expedition sent by the Pacific Fur Company to Fort Astoria in 1810[85]

- George Flavel, maritime pilot and businessman

- Charles William Fulton, lawyer and Oregon senator

- Jerry Gustafson, football player[86]

- Darrell Hanson, American politician in the state of Iowa

- Michael Hurley, American singer/songwriter[87]

- Duane Jarvis, American guitarist and singer/songwriter

- Wally Johansen, a college basketball guard who played for the University of Oregon when it won the inaugural NCAA Division I men's basketball tournament championship in 1938–1939

- Consuelo Kanaga, a photographer and writer who became well known for her photographs of African-Americans

- Augustus C. Kinney, a physician and scientist, was a leading expert on tuberculosis

- Kenneth Koe, chemist of Chinese descent, helped develop sertraline, which was branded and sold as Zoloft

- Carl W. Leick, a German born architect who moved to Astoria. His Astoria designs include the Captain George Flavel House, the Clatsop County Courthouse, and the Grace Episcopal Church[88]

- Rosa Lemberg, a Namibian-born Finnish American teacher, choral conductor and socialist[89]

- Armand Lohikoski, American born – Finnish movie director and writer

- Robert Lundeen, American businessperson, most notable for his association with the College of Engineering at Oregon State University (OSU) and Tektronix Inc.[90]

- Ranald MacDonald, first man to teach the English language in Japan and one of the interpreters between the Tokugawa shogunate and Commodore Perry when the latter made his trips to Japan on behalf of the U.S. government in the early 1850s

- Holly Madison, Playboy model and one of Hugh Hefner's ex-girlfriends,[91] born in Astoria, but left before her second birthday

- Donald Malarkey, World War II U.S. Army soldier of the 101st Airborne Division who was portrayed in the television series Band of Brothers[92]

- Petra Mathers, a German-born American writer and illustrator of children's picture books

- George H. Merryman, a doctor who made house calls by horse and buggy then later built the first modern hospital in Klamath Falls. Served in both the Oregon House of Representatives & Oregon Senate

- Royal Nebeker, American painter and print maker. Lived and worked in Astoria for 30 years

- Gene Nelson, American dancer, actor, screenwriter, and director, starred as Will Parker in Oklahoma! (1955)

- Albin W. Norblad, Attorney in the U.S. state of Oregon, and a judge of the Oregon Circuit Court for the 3rd judicial district

- Kerttu Nuorteva, A Soviet intelligence agent during World War II. Daughter of Santeri Nuorteva

- Santeri Nuorteva, Finnish socialist politician and journalist, who edited Toveri ("The Comrade") in Astoria in 1912–1913[93] Father of Kerttu Nuorteva

- Maila Nurmi, a.k.a. 1950s TV horror hostess Vampira and co-star of Ed Wood's Plan 9 from Outer Space attended Astoria High School in the late 1930s[94]

- Mike Pecarovich, American college football coach, lawyer, and actor

- Allan Pomeroy, mayor of Seattle from 1952 to 1956[95]

- Jordan Poyer, NFL football player, raised in Astoria and played for Astoria teams[96]

- Ken Raymond, an expert in bioinorganic and coordination chemistry

- Sacagawea, a Lemhi Shoshone. The only female member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition to the Pacific in 1804–1806

- Arnie Sundberg, American weightlifter who competed in the 1932 Summer Olympics

- Wilbur Ternyik, American civic leader who has been characterized as a founding father of coastal planning. Mayor of Florence, Oregon

- Willis Van Dusen, businessman and mayor of Astoria from 1991 through 2014

- Gary Wilhelms, American politician who was a member of the Oregon House of Representatives

- Stanley Paul Young, American biologist[97]

- Eric Zener, American photorealist artist best known for figure paintings of lone subjects, often in or about swimming pools

- Grouper, American ambient musician, best known for her critically acclaimed album called Dragging a Dead Deer Up a Hill.

See also

- The Clatsop tribe of Native Americans

- Socialist Party of Oregon § The Finnish Socialists of Astoria

- Western Workmen's Co-operative Publishing Company

- Columbia Memorial Hospital

- Astoria Regional Airport

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Clatsop County, Oregon — 44 Astoria structures and districts listed (2020)

Image gallery

The replica of Fort Clatsop.

The replica of Fort Clatsop. Suomi Hall, the meeting hall of Finnish and Scandinavian immigrants, under the Astoria–Megler Bridge.

Suomi Hall, the meeting hall of Finnish and Scandinavian immigrants, under the Astoria–Megler Bridge..jpg.webp) Coast Guard cutter Alert docked at Astoria.

Coast Guard cutter Alert docked at Astoria. The Clatsop County Courthouse.

The Clatsop County Courthouse._(clatDA0016).jpg.webp) The Cannery Pier Hotel.

The Cannery Pier Hotel. The US Coast Guard pier.

The US Coast Guard pier. The Norwegian Pearl cruise ship docked at Astoria.

The Norwegian Pearl cruise ship docked at Astoria. The 1852 U.S. Custom's House.

The 1852 U.S. Custom's House..jpg.webp) The Flavel House Museum.

The Flavel House Museum. The Columbia River Maritime Museum.

The Columbia River Maritime Museum..jpg.webp) The Liberty Theatre located in the Astor Building.

The Liberty Theatre located in the Astor Building. The bicentennial Welcome to Astoria sign.

The bicentennial Welcome to Astoria sign._(clatDA0020c).jpg.webp) The Old Columbia Hospital Building.

The Old Columbia Hospital Building._(clatDA0016a).jpg.webp) The Heritage Museum, located in the former Astoria City Hall.

The Heritage Museum, located in the former Astoria City Hall. The former John Jacob Astor Hotel.

The former John Jacob Astor Hotel..jpg.webp) Former cannery dock pilings at Astoria waterfront.

Former cannery dock pilings at Astoria waterfront. An aerial view of the Astoria waterfront and Tongue Point in the distance.

An aerial view of the Astoria waterfront and Tongue Point in the distance._(clatD0067).jpg.webp) A Chinookan Indian Burial Canoe replica at the top of Coxcomb Hill.

A Chinookan Indian Burial Canoe replica at the top of Coxcomb Hill.

References

- Leeds, W. H. (1899). "Special Laws". The State of Oregon General and Special Laws and Joint Resolutions and Memorials Enacted and Adopted by the Twentieth Regular Session of the Legislative Assembly. Salem, Oregon: State Printer: 747.

- "ArcGIS REST Services Directory". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 12, 2022.

- "Census Population API". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 12, 2022.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- Lescroart 2009, p. 981.

- "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Astoria city, Oregon". www.census.gov. Retrieved January 25, 2023.

- Rebecca Sedlak (August 2, 2012). "First archaeological dig 'scratches the surface' of Fort Astoria’s history". The Daily Astorian. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- Galm, Jerry R., (1989), Prehistoric Trade and Exchange in the Columbia Plateau, Paper presented at the 42nd Annual Northwest Anthropological Conference, Spokane, Washington. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- William Clark; Meriwether Lewis (2015). The Journals of Lewis and Clark, 1804–1806 (Library of Alexandria ed.). Library of Alexandria. ISBN 978-1-613-10310-4.

- "History & Culture: Places: Fort Clatsop – "The National Park Service maintains a replica fort within the Lewis and Clark National Historical Park that is believed to sit on or near the site of the original fort."". National Park Service / U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved May 12, 2016.

- Meinig 1995, pp. 37–38, 50.

- Ronda, James (1995). Astoria & Empire. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-3896-7.

- United States Department of State (November 1, 2007). Treaties In Force: A List of Treaties and Other International Agreements of the United States in Force on November 1, 2007. Section 1: Bilateral Treaties (PDF). Compiled by the Treaty Affairs Staff, Office of the Legal Adviser, U.S. Department of State. (2007 ed.). Washington, DC. p. 320. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Lauterpacht 2004, p. 8.

- In his introduction to the rambling work, Irving reports that Astor explicitly "expressed a regret that the true nature and extent of his enterprizeand its national character and importance had never been understood."

- Collections of the Kansas State Historical Society, Volume 9. Kansas State Historical Society. 1906. p. 105.

- "Convention of Commerce between His Majesty and the United States of America.—Signed at London, 20th October 1818". Canado-American Treaties. Université de Montréal. 2000. Archived from the original on April 11, 2009. Retrieved March 27, 2006.

- "Oregon Territorials – Oregon Sesquicentennial exhibit online version.pdf" (PDF). Pacific Northwest Postal History Society. 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 20, 2015. Retrieved November 11, 2014.

- "The Swedes of Oregon".

- Chelsea Gorrow (April 16, 2012). "Astoria Embraces Chinese Legacy". The Daily Astorian.

- American Swedish Historical Museum: Yearbook 1946. American Swedish Hist Museum. ISBN 9781437950021.

- Ogden, Johanna (Summer 2012). "Ghadar, Historical Silences, and Notions of Belonging: Early 1900s Punjabis of the Columbia River". Oregon Historical Quarterly. 113 (2): 164–197 (34 pages). doi:10.5403/oregonhistq.113.2.0164. JSTOR 10.5403/oregonhistq.113.2.0164. S2CID 164468099.

- Terry, John (December 25, 2010). "Infernos leave historic marks on Astoria's waterfront". The Oregonian/OregonLive.

- Dresbeck, Rachel (July 15, 2015). "Chapter 3 – Port Town in Flames – The Astoria Fire – 1922". Oregon Disasters: True Stories of Tragedy and Survival. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9781493013197.

- "Callendar Navigation Co.", Morning Astorian (schedule), Astoria OR: J.S. Dellinger Co., vol. 59, no. 177, p. 6, col.3, May 9, 1905

- "Report of Committee on Manufacturies". The Morning Astorian. May 22, 1906. p. 5. Retrieved May 21, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

"Ethics and Business". The Morning Astorian. May 22, 1906. p. 2. Retrieved May 21, 2022 – via Newspapers.com. - "Emil Schimpff Ends His Life". The Times-Tribune. Scranton, Pennsylvania. February 17, 1903. p. 4. Retrieved May 21, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- Hankel, Evelyn G. (Fall 1989). "Early Astonian Breweries". CUMTUX. 9 (4): 21 – via Internet Archive.

- "Working and Repairing". The Morning Astorian. March 28, 1908. p. 5. Retrieved May 21, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "3". South Tongue Point Land Exchange and Marine Industrial Park Development Project, Clatsop County: Environmental Impact Statement. US Dept of Interior: Fish & Wildlife Service. 1992. p. 53. Retrieved November 21, 2021.

- Anderson, John Gottberg (June 21, 2015). "Going "Goonie" in Astoria". Bend Bulletin.

- Smith 1989, p. 299.

- "Report: Astoria tops West Coast fishing ports". Associated Press. October 29, 2014. Archived from the original on August 8, 2016. Retrieved May 31, 2016.

- Muldoon, Katy (May 14, 2009). "Swine flu sends cruise ship, tourism dollars to Astoria". The Oregonian/OregonLive.

- Edward Stratton (August 11, 2015). "Keeping fishing fever in check". The Daily Astorian. Retrieved May 30, 2016.

- Bill Monroe (August 8, 2015). "Early success at Buoy 10 promises good fall season ahead for salmon fishing". The Oregonian/OregonLive. Retrieved May 30, 2016.

- Andrew McKean (August 2015). "The Bite: Salmon Fishing the Columbia River". Outdoor Life. Retrieved May 30, 2016.

- Edward Stratton (May 24, 2016). "Sour beer to join Astoria's impressive brewing lineup". The Daily Astorian. Retrieved May 30, 2016.

- "Astoria Sunday Market – Astoria, OR". National Farmers Market Directory. Retrieved May 30, 2016.

- "Astoria Column, Coxcomb Hill". Spokesman-Review. Spokane, Washington. Associated Press. July 13, 1926. p. 7.

- "The Column at Astoria". Eugene Guard. Oregon. July 24, 1926. p. 4.

- Sharon Boorstin (June 2005). "Rhyme or Cut Bait When these fisher poets gather, nobody brags about the verse that got away". Smithsonian Magazine.

- Colin Murphey (February 17, 2019). "Festival of Dark Arts". The Daily Astorian.

- "TransAmerica Trail Summary". Adventure Cycling Association. Archived from the original on January 12, 2013. Retrieved December 26, 2012.

- Edward Stratton (September 16, 2015). "New commander takes Steadfast's helm". EO Media Group / chinookobserver. Retrieved May 12, 2016.

- "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 12, 2012. Retrieved December 21, 2012.

- "Climate of Clatsop County". Oregon State University. Archived from the original on July 30, 2016. Retrieved April 22, 2016.

- Local Climatological Data - Annual Summary with Comparative Data https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/pub/data/lcd/annual/2002/2002AST.pdf

- Aladin. "Astoria, OR - Climate & Monthly weather forecast". Weather U.S. Retrieved January 25, 2023.

- "Average Relative Humidity – Morning (M), Afternoon (A)" (PDF). Comparative Climatic Data for the United States Through 2012. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 18, 2014.

- "Station Name: OR ASTORIA RGNL AP". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 13, 2013.

- "NOWData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- "Astoria, Oregon (350324)". Western Regional Climate Center. Retrieved December 31, 2013.

- "Astoria WSO Airport, Oregon (350328)". Western Regional Climate Center. Retrieved December 31, 2013.

- "U.S. Climate Normals Quick Access – Station: Astoria RGNL AP, OR (1991–2020)". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on September 6, 2023. Retrieved December 30, 2022.

- "U.S. Climate Normals Quick Access – Station: Astoria Regional Airport, OR (1981–2010)". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on September 6, 2023. Retrieved December 30, 2022.

- "WMO climate normals for ASTORIA/CLATSOP, OR 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on September 6, 2023. Retrieved September 6, 2023.

- "2010 Census profiles: Oregon cities alphabetically A-C" (PDF). Portland State University Population Research Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 3, 2016. Retrieved June 12, 2011.

- Moffat, Riley. Population History of Western U.S. Cities & Towns, 1850–1990. Lanham: Scarecrow, 1996, 206.

- "Subcounty population estimates: Oregon 2000–2007". United States Census Bureau, Population Division. March 18, 2009. Archived from the original (CSV) on July 9, 2009. Retrieved May 3, 2009.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 21, 2012.

- "City Council". City of Astoria. Retrieved December 22, 2015.

- "Seamanship | Job Corps". jobcorps.gov. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- Newspapers Published in Oregon Oregon Blue Book. Retrieved July 22, 2012.

- "Oregon Newspaper Publishers Century Roster" (PDF). Oregon Publisher. The Oregon Newspaper Publishers Association. June 2012. p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 19, 2012. Retrieved November 25, 2014.

- "Coast River Business Journal – About Us". Archived from the original on September 28, 2016. Retrieved May 30, 2016.

- "Astoria Theatre Sign". March 18, 2007.

- John, Finn J.D. (September 19, 2011). "Astoria man set out to do something nice for his wife, ended up inventing cable TV". Offbeat Oregon History. Retrieved December 31, 2013.

- "One Tiger to a Hill". IMDb. September 21, 1962.

- "Shanghaied in Astoria Announces 2017 Showdates". coastexplorermagazine.com. May 12, 2017. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- Sonja Stewart (May 16, 2011). "Visit Your Favorite Family Movie Locations in Astoria, Oregon". Parenting Squad. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

- "Movies filmed in Astoria Oregon". Astoria Oregon. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

- Ryan S. (a.k.a. Spoodawg) (July 8, 2010). "Guest blogger: How did I spend my vacation? Visiting 'Goonies' filming locations!". USA Today. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

- "Filmed in Oregon 1908–2012" (PDF). Oregon Governor's Office of Film & Television. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 14, 2014. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- KATIE KARPOWICZ. "The Ataris Hop on the Nostalgia Boat, Bring 'So Long, Astoria' Tour To Chicago". Gothamist LLC. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved May 13, 2016.

- Jane, Lauraa (September 15, 2015). "Marianas Trench To Release New Album 'Astoria'". Highlight Magazine. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

- Turnquist, Kristi (September 23, 2013). "'Dexter' series finale leaves its antihero with a new life – in Oregon". The Oregonian. Retrieved November 29, 2021.

From Miami to Astoria: In the series finale of "Dexter," Michael C. Hall's serial killer character winds up in Astoria, Oregon.

- Joe James Custer (1944). Through the Perilous Night: The Astoria's Last Battle. The Macmillan Company.

- "Astoria III (CL-90)". Naval History and Heritage Command. June 19, 2015. Retrieved December 12, 2015.

- "Interactive City Directory". Sister Cities International. Archived from the original on August 13, 2014. Retrieved December 31, 2013.

- Ebeling 1998, pp. 351–354.

- AHS Hall of Fame

- "Brian Bruney Stats". Baseball Almanac. Retrieved December 31, 2013.

- Lynn, Capi (April 5, 2005). "She Should Be As Famous As Sacagawea". Statesman Journal. Salem, Oregon. Archived from the original on February 3, 2013. Retrieved October 24, 2008.

- "Jerry F. Gustafson". fanbase.com. Archived from the original on August 12, 2014. Retrieved August 9, 2014.

- Brinkman, Brian R. (May 11, 2011). "Wading in cerebrospinal fluid with Cass McCombs, Frank Fairfield and Michael Hurley". Oregon Music News. Archived from the original on January 2, 2014. Retrieved December 31, 2013.

- "National Register of Historic Places Nomination and Registration Forms: Mukilteo Light Station". National Park Service. October 21, 1977. Retrieved June 8, 2015.

- Rosemont, Franklin (2003). Joe Hill: The IWW & The Making of a Revolutionary Working Class Counterculture. Chicago, Illinois: Charles H Kerr. ISBN 978-088-28626-4-4.

- "Lundeen Made Lasting Impact at Oregon State". Retrieved May 11, 2016.

- TMZ.com (October 7, 2008). "Holly to Hugh: Hef Off". Retrieved October 7, 2008.

- NW Spotlight (November 11, 2011). "Veterans Day tribute to an Oregon hero: Don Malarkey". OregonCatalyst. Retrieved December 31, 2013.

- Paul George Hummasti, Finnish Radicals in Astoria, Oregon, 1904–1940: A Study in Immigrant Socialism. New York: Arno Press, 1979; p. 44.

- "Vampira: The haunting of Astoria High School". The Daily Astorian. October 31, 2008. Archived from the original on January 1, 2014. Retrieved December 31, 2013.

- "Mayors, 1948 – Present". Seattle Municipal Archives.

- "Small-town Jordan Poyer hopes to make it big time with the Cleveland Browns as a defensive back". December 13, 2013.

- "Biography". Smithsonian Institution Archives. Retrieved June 19, 2013.

Sources

- Ebeling, Herbert C. (1998). Johann Jakob Astor, Walldorf Astor-Stiftung. Astor-Stiftung. ISBN 3-00-003749-7.

- Elihu Lauterpacht; C. J. Greenwood; A. G. Oppenheimer; Karen Lee, eds. (2004). "Consolidated Table of Treaties, Volumes 1–125" (PDF). International Law Reports. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-80779-4. OCLC 56448442. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- Lescroart, Justine (2009). Roadtripping USA. New York: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-312-38583-5.

- Meinig, D.W. (1995) [1968]. The Great Columbia Plain (Weyerhaeuser Environmental Classic ed.). University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-97485-9.

- Smith, Dwight A.; Norman, James B.; Dykman, Pieter T. (1989). Historic Highway Bridges of Oregon. Oregon Historical Society Press. ISBN 0-87595-205-4.

Further reading

- Ebeling, Herbert C.: Johann Jakob Astor. Walldorf, Germany: Astor-Stiftung, 1998. ISBN 3-00-003749-7.

- Leedom, Karen L.: Astoria: An Oregon History. Astoria, Oregon: Rivertide Publishing, 2008. ISBN 978-0-9826252-1-7.

- MacGibbon, Elma (1904). Leaves of knowledge. Shaw & Borden Co. Elma MacGibbons reminiscences about her travels in the United States starting in 1898, which were mainly in Oregon and Washington. Includes chapter "Astoria and the Columbia River".

External links

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- Entry for Astoria in the Oregon Blue Book

- Astoria-Warrenton Chamber of Commerce

- Astoria Documentary produced by Oregon Public Broadcasting

.jpg.webp)

_ASTORIA%252C_OREGON%252C_ENTRANCE_TO_COLUMBIA_RIVER.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

_off_Mare_Island_in_July_1941.jpg.webp)