Lake Atitlán

Lake Atitlán (Spanish: Lago de Atitlán, [atiˈtlan]) is a lake in the Guatemalan Highlands of the Sierra Madre mountain range. The lake is located in the Sololá Department of southwestern Guatemala. It is known as the deepest lake in Central America.

| Lake Atitlán | |

|---|---|

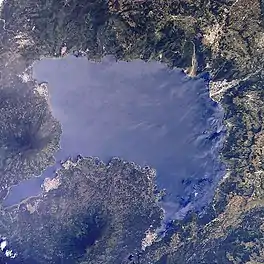

Seen from the Space Shuttle. Volcán San Pedro is at the left of the image; Panajachel is the largest white patch along the upper right shore. North is to the top of the image. | |

Lake Atitlán | |

| Location | Sololá Department |

| Coordinates | 14°42′N 91°12′W |

| Type | Crater lake, endorheic |

| Basin countries | Guatemala |

| Surface area | 130.1 km2 (50.2 sq mi)[1] |

| Average depth | 154 m (505 ft) |

| Max. depth | 340 m (1,120 ft) (est.) |

| Water volume | 20 km3 (16,000,000 acre⋅ft) |

| Surface elevation | 1,562 m (5,125 ft) |

| References | [1] |

Name

Atitlán means "between the waters". In the Nahuatl language, "atl" is the word for water,[2] and "titlan" means between.[3] The "tl" at the end of the word "atl" is dropped (because it is a grammatical suffix) and the words are combined to form "Atitlán".

Geography

The lake has a maximum depth of about 340 metres (1,120 ft)[1] and an average depth of 154 metres (505 ft).[4] Its surface area is 130.1 km2 (50.2 sq mi).[1] It is approximately 18 km × 8 km (11.2 mi × 5.0 mi) with around 20 km3 (4.8 cu mi) of water. Atitlán is technically an endorheic lake, feeding from two nearby rivers and not draining into the ocean. It is shaped by deep surrounding escarpments and three volcanoes on its southern flank. The lake basin is volcanic in origin, filling an enormous caldera formed by a supervolcanic eruption 84,000 years ago. The culture of the towns and villages surrounding Lake Atitlán is influenced by the Maya people. The lake is about 50 kilometres (31 mi) west-northwest of Antigua. It should not be confused with the smaller Lake Amatitlán.

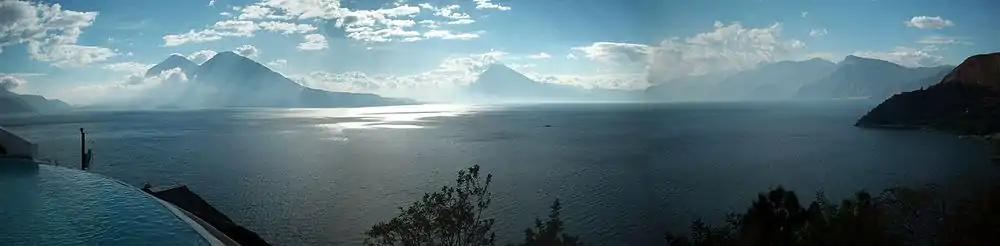

Lake Atitlán is renowned as one of the most beautiful lakes in the world, and is one of Guatemala's most important national and international tourist attractions.[4] German explorer and naturalist Alexander von Humboldt called it "the most beautiful lake in the world,"[5] and Aldous Huxley famously wrote of it in his 1934 travel book Beyond the Mexique Bay: "Lake Como, it seems to me, touches on the limit of permissibly picturesque, but Atitlán is Como with additional embellishments of several immense volcanoes. It really is too much of a good thing."[6]

The area around San Marcos has particularly tall cliffs abutting the lake and in recent years has become renowned for cliff diving.[7]

Agriculture

The area supports extensive coffee and avocado orchards and a variety of farm crops, most notably corn and onions. Significant agricultural crops include: corn, onions, beans, squash, tomatoes, cucumbers, garlic, chile verde, strawberries and pitahaya fruit. The lake itself is a significant food source for the largely indigenous population.

Geological history

The first volcanic activity in the region occurred about 11 million years ago, and since then the region has seen four separate episodes of volcanic growth and caldera collapse, the most recent of which began about 1.8 million years ago and culminated in the formation of the present caldera. The lake now fills a large part of the caldera, reaching depths of up to 340 m (1,120 ft).

The caldera-forming eruption is known as Los Chocoyos eruption and ejected up to 300 km3 (72 cu mi) of tephra. The enormous eruption dispersed ash over an area of some 6,000,000 square kilometres (2,300,000 sq mi): it has been detected from Florida to Ecuador, and can be used as a stratigraphic marker in both the Pacific and Atlantic oceans (known as Y-8 ash in marine deposits).[8] A chocoyo is a type of bird which is often found nesting in the relatively soft ash layer.

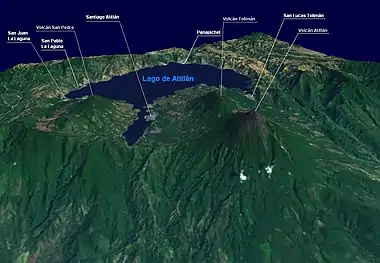

Since the end of Los Chocoyos, continuing volcanic activity has built three volcanoes in the caldera. Volcán Atitlán lies on the southern rim of the caldera, while Volcán San Pedro and Volcán Tolimán lie within the caldera. San Pedro is the oldest of the three and seems to have stopped erupting about 40,000 years ago. Tolimán began growing after San Pedro stopped erupting and probably remains active, although it has not erupted in historic times. Atitlán has developed almost entirely in the last 10,000 years and remains active, its most recent eruption having occurred in 1853.

On February 4, 1976, a very large earthquake (magnitude 7.5) struck Guatemala, killing more than 26,000 people. The earthquake fractured the lake bed and caused subsurface drainage from the lake, allowing the water level to drop two metres (6 ft 7 in) within one month.[9][10]

Ecological history

In 1955, the area around Lake Atitlán became a national park. The lake was mostly unknown to the rest of the world, and Guatemala was seeking ways to increase tourism and boost the local economy. It was suggested by Pan American World Airways that stocking the lake with a fish prized by anglers would be a way to do just that.[11] As a result, an exotic non-native species, the black bass, was introduced into the lake in 1958. The bass quickly took to its new home and caused a radical change in the species composition of the lake. The predatory bass caused the elimination of more than two-thirds of the native fish species in the lake and contributed to the extinction of the Atitlan grebe, a rare bird that lived only in the vicinity of Lake Atitlán.[12]

A unique aspect of the climate is what is referred to as Xocomil (of the Kaqchickel language meaning "the wind that carried away sin"). This wind is common late morning and afternoon across the lake; it is said to be the encounter of warm winds from Pacific meeting colder winds from the North. The winds can result in violent water turbulence, enough to capsize boats.[13]

In August 2015 a thick bloom of algae known as Microcystis cyanobacteria re-appeared in Lake Atitlan; the first major occurrence was in 2009. Bureaucratic red tape has been blamed for the lack of action to save the lake. If current activities continue unchecked, the toxification of the lake will make it unsuitable for human use.[14]

Culture

The lake is surrounded by many villages in which Maya culture is still prevalent and traditional dress is worn. The Maya people of Atitlán are predominantly Tz'utujil and Kaqchikel. During the Spanish conquest of the Americas, the Kaqchikel initially allied themselves with the invaders to defeat their historic enemies, the Tz'utujil and K'iche' Maya, but were themselves conquered and subdued when they refused to pay tribute to the Spanish.

Santiago Atitlán is the largest of the lakeside communities, and it is noted for its worship of Maximón, an idol formed by the fusion of traditional Mayan deities, Catholic saints, and conquistador legends. The institutionalized effigy of Maximón is under the control of a local religious brotherhood and resides in various houses of its membership during the course of a year, being most ceremonially moved in a grand procession during Semana Santa. Several towns in Guatemala have similar cults, most notably the cult of San Simón in Zunil.

While Maya culture is predominant in most lakeside communities, Panajachel has been overwhelmed over the years by Guatemalan and foreign tourists. It attracted many hippies in the 1960s, and although the civil war caused many foreigners to leave, the end of hostilities in 1996 saw visitor numbers boom again, and the town's economy is almost entirely reliant on tourism today.

Several Mayan archeological sites have been found at the lake. Sambaj, located approximately 55 feet below the current lake level, appears to be from at least the pre-classic period.[15] There are remains of multiple groups of buildings, including one particular group of large buildings that are believed to have been the city center.[16]

A second site, Chiutinamit, where the remains of a city were found, was discovered by local fishermen who "noticed what appeared to be a city underwater".[17] During subsequent investigations, pottery shards were recovered from the site by divers, which enabled the dating of the site to the late pre-classic period (300 B.C. – 300 A.D.),[18] more specifically 250 AD.[19]

A project titled "Underwater archeology in the Lake Atitlán. Sambaj 2003 Guatemala" was recently approved by the Government of Guatemala in cooperation with Fundación Albenga and the Lake Museum in Atitlán. Because of the concerns of a private organization as is the Lake Museum in Atitlán the need to start the exploration of the inland waters in Guatemala was analyzed.[20]

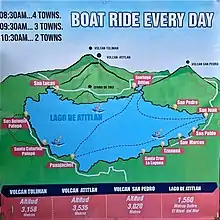

There is no road that circles the lake. Communities are reached by boat or roads from the mountains that may have brief extensions along the shore. Jaibalito can only be reached by boat. Santa Catarina Palopó and San Antonio Palopó are linked by road to Panajachel. Main places otherwise are Santa Clara La Laguna, San Juan La Laguna, and San Pedro La Laguna in the west; Santiago Atitlán in the south; Cerro de Oro in the southeast; and San Lucas Tolimán in the east.

Recent studies indicate that a ceremonial site named Samabaj was located on an island about 500 metres (1,600 ft) long in Lake Atitlán. The site was revered for its striking connection to the Popol Wuj of the K'iche' Mayan peoples.

Guatemalan civil war

During the Guatemalan Civil War (1960 - 1996), the lake was the scene of many terrible human rights abuses, as the government pursued a scorched earth policy.[21][22] Indigenous people were assumed to be universally supportive of the guerrillas who were fighting against the government, and were targeted for brutal reprisals.[21][22] Some believe that hundreds of Maya from Santiago Atitlán have disappeared during the conflict.[23][24]

Two events of this era made international news. One was the assassination of Stanley Rother, a missionary from Oklahoma, in the church at Santiago Atitlán in 1981.[25] In 1990, a spontaneous protest march to the army base on the edge of town was met by gunfire, resulting in the death of 11 unarmed civilians.[26] International pressure forced the Guatemalan government to close the base and declare Santiago Atitlán a "military-free zone". The memorial commemorating the massacre was damaged in the 2005 mudslide.

Hurricane

Torrential rains from Hurricane Stan caused extensive damage throughout Guatemala in early October 2005, particularly around Lake Atitlán. A massive landslide buried the lakeside village of Panabaj, causing the death of as many as 1,400 residents, leaving 5,000 homeless, and many bodies buried under tonnes of earth. Following this event, Diego Esquina Mendoza, the mayor of Santiago Atitlán, declared the community a mass gravesite: "Those buried by the mudslide may never be rescued. Here they will stay buried, under five meters of mud. Panabáj is now a cemetery."[27]

Four and a half years after Hurricane Stan, Tropical Storm Agatha dropped even more rainfall causing extensive damages to the region[28] resulting in dozens of deaths between San Lucas Tolimán and San Antonio Palopó. Since then roads have been reopened and travel to the region has returned to normal.

Gallery

Volcano Atitlan, San Pedro, Toliman & Lago Atitlan isometric view

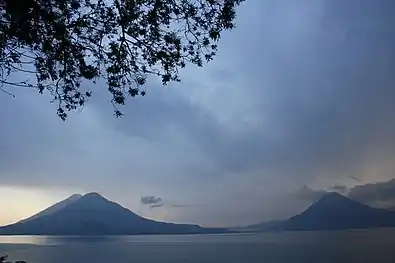

Volcano Atitlan, San Pedro, Toliman & Lago Atitlan isometric view Another view from the Lake

Another view from the Lake Storm over San Pedro volcano, 2015

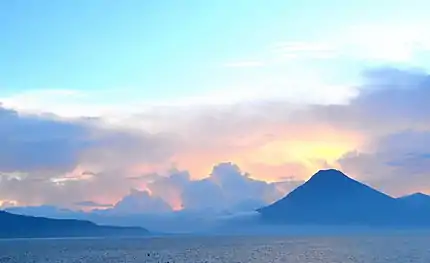

Storm over San Pedro volcano, 2015.jpg.webp) Sunrise at lake atitlán Guatemala

Sunrise at lake atitlán Guatemala Volcanoes of Lake Atitlan

Volcanoes of Lake Atitlan Lake Atitlán, seen from San Marcos Guatemala

Lake Atitlán, seen from San Marcos Guatemala Fisherman in Lake Atitlán

Fisherman in Lake Atitlán.jpg.webp) Lake Atitlán and volcanoes

Lake Atitlán and volcanoes Hotel on the shores of Lake Atitlán Guatemala

Hotel on the shores of Lake Atitlán Guatemala Panajachel

Panajachel.jpg.webp) Lake Atitlan & volcanoes from the East

Lake Atitlan & volcanoes from the East Clouds, mountains, lakes

Clouds, mountains, lakes A harmful bloom of cyanobacteria (blue-green algae) spread across the lake (false color image)

A harmful bloom of cyanobacteria (blue-green algae) spread across the lake (false color image).jpg.webp) Hike down from the east rim to Lake Atitlán

Hike down from the east rim to Lake Atitlán.jpg.webp) Hike down from the east rim to Lake Atitlán-Panajachel

Hike down from the east rim to Lake Atitlán-Panajachel.jpg.webp) Hike down from the east rim to Lake Atitlán-Panajachel

Hike down from the east rim to Lake Atitlán-Panajachel Santiago Atitlán map

Santiago Atitlán map Lake Atitlán Guatemala

Lake Atitlán Guatemala Panorama of Lake Atitlán, Guatemala

Panorama of Lake Atitlán, Guatemala Volcanoes near Lake Atitlán Guatemala

Volcanoes near Lake Atitlán Guatemala Town Street, Lake Atitlán, Guatemala with Volcano

Town Street, Lake Atitlán, Guatemala with Volcano Indigenous people near Lake Atitlán Guatemala

Indigenous people near Lake Atitlán Guatemala Solalá

Solalá Guatemala Panjachel sunset

Guatemala Panjachel sunset Indigenous girls

Indigenous girls Panajachel shore

Panajachel shore View of a lancha and Volcán Atitlán from Hotel La Casa del Mundo

View of a lancha and Volcán Atitlán from Hotel La Casa del Mundo

See also

Notes

- INSIVUMEH (2008). "Indice de lagos" (in Spanish).

- "atl - Wiktionary". en.wiktionary.org. Retrieved 2018-08-17.

- "-titlan - Wikcionario". es.wiktionary.org (in Spanish). Retrieved 2018-08-17.

- "Atitlan, Lago Profile". LakeNet. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- Morgan Szybist, Richard (2004). The Lake Atitlan Reference Guide: The Definitive Eco-Cultural Guidebook on Lake Atitlan. Adventures in Education, Inc.

- Fieser, Ezra (November 29, 2009). "How Guatemala's Most Beautiful Lake Turned Ugly". Time. Retrieved 2021-07-18.

- "Lake Atitlan, Guatemala". The Travelers Within. Retrieved 2020-07-10.

- Rose, William I.; et al. (1987). "Quaternary silicic pyroclastic deposits of Atitlán Caldera, Guatemala". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 33 (1–3): 57–80. Bibcode:1987JVGR...33...57R. doi:10.1016/0377-0273(87)90054-0.

- "Guatemala Volcanoes and Volcanics". USGS – CVO. Retrieved 2010-03-13.

- Newhall, C.G.; Paull, C.K.; Bradbury, J.P.; Higuera-Gundy, A.; Poppe, L.J.; Self, S.; Bonar Sharpless, N.; Ziagos, J. (August 1987). "Recent geologic history of lake Atitlán, a caldera lake in western Guatemala". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 33 (1–3): 81–107. Bibcode:1987JVGR...33...81N. doi:10.1016/0377-0273(87)90055-2.

- "Bad-Ass Bass Rain from the Sky – Revue Magazine". Archived from the original on 2017-04-09. Retrieved 2016-05-30.

- "Bad-Ass Bass Rain from the Sky - Revue Magazine". revuemag.com. 29 August 2011. Archived from the original on 9 April 2017. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

- Pérez, César (14 November 2018). "Xocomil, el fenómeno del Lago de Atitlán que hizo volcar una lancha con 17 personas" [Xocomil, the Lake Atitlan phenomenon that made a boat with 17 people flip]. Prensa Libre. Archived from the original on 16 November 2018. Retrieved 16 Nov 2018.

- "Toxic Algae Invade Guatemala's Treasured Lake Atitlan". ens-newswire.com. 20 August 2015.

- Henry Benítez and Roberto Samayoa, "Samabaj y la arqueología subacuática en el Lago de Atitlán," in XIII Simposio de Investigaciones Arqueológicas en Guatemala, 1999 (Guatemala: Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología, 2000), 2:849–54.

- Sorenson, John L., (2002) The Submergence of the City of Jerusalem in the Land of Nephi, Provo, Utah: Maxwell Institute, 2002. P. N/A

- Lund, John L. (2007), Mesoamerica and the Book of Mormon: Is this the Place, p. 61

- Allen, Joseph (2003), Sacred Sites, p. 34

- "Divers probe Mayan ruins submerged in Guatemala lake". Reuters. 30 October 2009. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

- http://www.unesco.org.cu/SitioSubacuatico/english/06_monica_valentini.htm%5B%5D

- United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (1990-07-27). "Guatemala. Democracy and Human Rights". Refworld. Retrieved 2023-07-30.

- "Guatemala: All the truth, justice for all". Amnesty International. 1998-05-12. AMR 34/002/1998. Retrieved 2023-07-30.

- Flynn, James E. (2009-02-08). "A Pilgrimage and Retreat in Guatemala: Jan. 14-25, 2008". Intermountain Catholic. Retrieved 2023-07-30.

- "Our Story – Hospitalito Atitlán". Hospitalito Atitlán. 2005-04-01. Retrieved 2023-07-30.

- "Oklahoma Missionary Murdered in Guatemala". Archdiocese of Oklahoma City. Archived from the original on 24 October 2015. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- "Guatemala Troops Said to Kill 11 Protesting Raid". The New York Times. 3 December 1990. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- "Hurricane Stan and Social Suffering in Guatemala". David Rockefeller Center Harvard.edu. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- "Agatha". May 2010. p. 6. Archived from the original on 2010-06-07. and the effects of Tropical Storm Agatha

Further reading

- Morgan Szybist, Richard (2004), The Lake Atitlan Reference Guide: The Definitive Eco-Cultural Guidebook on Lake Atitlan, Adventures in Education, Inc.

- Newhall, Christopher G., Dzurisin, Daniel (1988); Historical unrest at large calderas of the world, USGS Bulletin 1855 Archived 2009-05-12 at the Wayback Machine, p. 1108

- Vallance J.W., Calvert A.T. (2003), Volcanism during the past 84 ka at Atitlan caldera, Guatemala, American Geophysical Union, Fall Meeting 2003

- Kingery, Dennis (2003), Improving on Nature?, National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science

- Maudslay, Alfred Percival; Maudslay, Anne Cary (1899). A glimpse at Guatemala, and some notes on the ancient monuments of Central America (PDF). London, UK: John Murray.

External links

- AMSCLAE Authority Lake Atitlan

- Volcano World Information Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine