Atlantic Bronze Age

The Atlantic Bronze Age is a cultural complex of the Bronze Age period in Prehistoric Europe of approximately 1300–700 BC that includes different cultures in Britain, France, Ireland, Portugal, and Spain.

| |

| Geographical range | Western Europe |

|---|---|

| Period | Bronze Age |

| Dates | c. 1300 — c. 700 BC |

| Preceded by | Bell Beaker culture, Bronze Age Britain, Armorican Tumulus culture, Wessex culture |

| Followed by | Iron Age Britain, Iron Age Ireland, Iron Age France, Iron Age Spain |

Trade

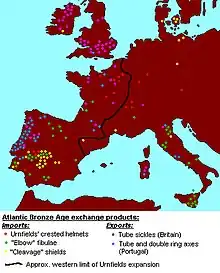

The Atlantic Bronze Age is marked by economic and cultural exchange that led to the high degree of cultural similarity exhibited by the coastal communities from Central Portugal to Galicia, Armorica, Cornwall and Scotland, including the frequent use of stones as chevaux-de-frise, the establishment of cliff castles, or the domestic architecture sometimes characterized by the roundhouses.[1] Commercial contacts extended from Sweden[2] and Denmark to the Mediterranean.[1] The period was defined by a number of distinct regional centres of metal production, unified by a regular maritime exchange of some of their products. The major centres were southern England and Ireland, north-western France, and western Iberia.[3]

The items related to this culture are frequently found forming hoards, or they are deposited in ritual areas,[4][5] usually watery contexts: rivers, lakes and bogs. Among the more noted items belonging to this cultural complex we can count the socketed and double ring bronze axes, sometimes buried forming large hoards in Brittany and Galicia; war gear, as lunate spearheads, V-notched shields, and a variety of bronze swords —among them carp's-tongue ones— usually found deposited in lakes, rivers or rocky outcrops;[6] and the elites' feasting gear: articulated roasting spits, cauldrons, and flesh hooks,[5][7] found from central Portugal to Scotland.[1]

The origins of the Celts were attributed to this period in 2008 by John T. Koch[8] and supported by Barry Cunliffe,[9] who argued for the past development of Celtic as an Atlantic lingua franca, later spreading into mainland Europe.[5] They argue that communities adopted early Late Bronze Age Urnfield (Bronze D and Hallstatt A) elite status markers such as grip-tongue swords and sheet-bronze metalwork, along with new specialist know-how needed for their production and ritual knowledge about their 'proper' treatment upon deposition[10] which they see as indicating possible processes linked to language shift.[10] In 2013, Koch saw this east to west elite contact as the simplest explanation for the genesis of Celtic languages with a Proto-Celtic homeland in west-central Europe.[11] However, this stands in contrast to what remains the more generally accepted view that Celtic origins lie with the Central European Hallstatt C culture.

Gallery

A Bronze Age gold hoard: Tesouro de Caldas, Galicia, Spain

A Bronze Age gold hoard: Tesouro de Caldas, Galicia, Spain Gold torque from Stretham, England

Gold torque from Stretham, England Bronze weapons from Lanzahíta, Spain

Bronze weapons from Lanzahíta, Spain Bronze Age swords, France

Bronze Age swords, France The Caergwrle Bowl, Wales, c. 1300 BC

The Caergwrle Bowl, Wales, c. 1300 BC Casco de Leiro, Galicia, Spain

Casco de Leiro, Galicia, Spain_01.jpg.webp) Gold bowls from Axtroki, Spain

Gold bowls from Axtroki, Spain.jpg.webp) Gold bracelets and neckrings from Milton Keynes, England

Gold bracelets and neckrings from Milton Keynes, England Sintra collar, Portugal, c. 10th century BC

Sintra collar, Portugal, c. 10th century BC![Bronze cauldrons. Left Cabárceno [es], Spain. Right Chiseldon, England.](../I/Atlantic_Bronze_Age_riveted_cauldrons._Left_Cantabria%252C_Spain._Right_Chiseldon%252C_UK.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp) Gold and bronze hoard from Wrexham, Wales

Gold and bronze hoard from Wrexham, Wales Gold torque or belt from Guînes, France, 1300-1150 BC[14]

Gold torque or belt from Guînes, France, 1300-1150 BC[14] Gold torque from Guînes, Pas-de-Calais, France.[15]

Gold torque from Guînes, Pas-de-Calais, France.[15] Deposito da Samieira, a hoard of Galician Bronze Age axes. Museo de Pontevedra

Deposito da Samieira, a hoard of Galician Bronze Age axes. Museo de Pontevedra Stele of Solana de Cabañas, Spain.

Stele of Solana de Cabañas, Spain. Adabrock Hoard, Scotland, c. 1000 BC

Adabrock Hoard, Scotland, c. 1000 BC Gold torque from the Treasure of Berzocana, Extremadura, Spain

Gold torque from the Treasure of Berzocana, Extremadura, Spain Ceremonial bronze dirk, France, c. 1300 BC

Ceremonial bronze dirk, France, c. 1300 BC Dirks from England and France

Dirks from England and France Brazalete da Urdiñeira, Spain

Brazalete da Urdiñeira, Spain Gold torc, Saint-Jean-Trolimon, France

Gold torc, Saint-Jean-Trolimon, France Bronze axes, France

Bronze axes, France Gold disk/ring, Extremadura, Spain, c. 1000 BC

Gold disk/ring, Extremadura, Spain, c. 1000 BC Dún Aonghasa hillfort, Ireland

Dún Aonghasa hillfort, Ireland

See also

References

- Cunliffe, Barry (1999). "Atlantic Sea-ways" (PDF). Revista de Guimarães. Especial (I): 93–105. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 20 September 2011.

- Ling, Johan; Stos-Gale, Zofia; Grandin, Lena; Billström, Kjell; Hjärthner-Holdar, Eva; Persson, Per-Olof (2014). "Moving metals II: provenancing Scandinavian Bronze Age artefacts by lead isotope and elemental analyses". Journal of Archaeological Science. 41: 106–132. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2013.07.018.

- Europe Before History by Kristian Kristiansen Archived May 8, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- Comendador Rey, Beatriz. "SPACE AND MEMORY AT THE MOUTH OF THE RIVER ULLA (GALICIA, SPAIN)" (PDF). Conceptualising Space and Place: On the role of agency, memory and identity in the construction of space from the Upper Palaeolithic to the Iron Age in Europe. Archaeopress. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- Cunliffe, Barry (2008). Europe between the oceans : themes and variations, 9000 BC-AD 1000 (First printed in paperback 2011. ed.). New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 254–258. ISBN 978-0-300-17086-3.

- Quilliec, Bénédicte T. (2007). "Vida y muerte de una espada atlántica del Bronce Final en Europa: Reconstrucción de los procesos de fabricación, uso y destrucción" [Life and death of an Atlantic sword: Reconstruction of the processes of fabrication, use wear and destruction]. Complutum (in Spanish). 18: 93–107. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- Bowman, Sheridan; Stuart Needham (2007). "The Dunaverney and Little Thetford Flesh-Hooks: History, Technology and Their Position within the Later Bronze Age Atlantic Zone Feasting Complex" (PDF). The Antiquaries Journal. 87: 53–108. doi:10.1017/s0003581500000846. S2CID 161084139. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- Koch, John (2009). Tartessian: Celtic from the Southwest at the Dawn of History in Acta Palaeohispanica X Palaeohispanica 9 (2009) (PDF). Palaeohispanica. pp. 339–351. ISSN 1578-5386. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 June 2010. Retrieved 17 May 2010.

- Cunliffe, Barry (2008). A Race Apart: Insularity and Connectivity in Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 75, 2009, pp. 55–64. The Prehistoric Society. p. 61.

- Brandherm, Dirk (2013). Celtic from the West 2 - Westward Ho? Sword-bearers and all the rest of it... Oxford: Oxbow Books. p. 148. ISBN 978-1-84217-529-3. Archived from the original on 21 January 2013.

- Koch, John T. (2013). Celtic from the West 2 -Prologue: The Earliest Hallstatt Iron Age cannot equal Proto-Celtic. Oxford: Oxbow Books. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-84217-529-3. Archived from the original on 21 January 2013.

- Gerloff, Sabine (1986). "Bronze Age Class A Cauldrons: Typology, Origins and Chronology". The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland. 116: 84–115.

- Barrowclough, David (2014). Bronze Age Feasting Equipment: A contextual discussion of the Salle and East Anglian cauldrons and flesh-hooks. Red Dagger Press, Cambridge. pp. 1–17.

- Armbruster, Barbara (2013). "Gold and gold working of the Bronze Age". The Oxford Handbook of the European Bronze Age. pp. 454–468.

- Armbruster (2016). "Manufacturing processes of Atlantic Bronze Age annular gold ornaments—A case study of the Guînes gold hard (Pas-de-Calais, France)". Materials and Manufacturing Processes. 32 (7–8): 728–739. doi:10.1080/10426914.2016.1232819. S2CID 114317154.

External links

- Spaniards search for legendary Tartessos in a marsh

- Moor Sands finds, including a remarkably well preserved and complete sword which has parallels with material from the Seine basin of northern France

- 3000-year-old shipwreck shows European trade was thriving in Bronze Age

- Scales, weights and weight-regulated artefacts in Middle and Late Bronze Age Britain (Lorenz Rahmstorf 2019)