Atlantic Seaboard Fall Line

The Atlantic Seaboard Fall Line, or Fall Zone, is a 900-mile (1,400 km) escarpment where the Piedmont and Atlantic coastal plain meet in the eastern United States.[2] Much of the Atlantic Seaboard fall line passes through areas where no evidence of faulting is present.

Atlantic Seaboard fall line | |

|---|---|

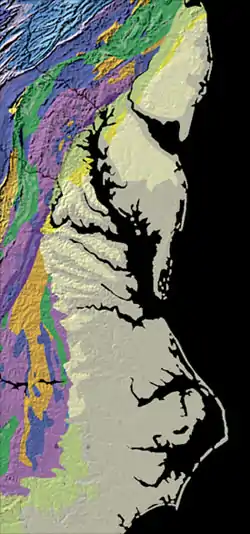

Map showing part of the Eastern Seaboard Fall Line where the pale colored coastal plain meets the brightly colored Piedmont. | |

| Location | United States |

| Formed by | New Jersey Carolinas or Georgia[1][2] |

| Dimensions | |

| • Length | 900 mi (1,400 km)[2] |

The fall line marks the geologic boundary of hard metamorphosed terrain—the product of the Taconic orogeny—and the sandy, relatively flat alluvial plain of the upper continental shelf, formed of unconsolidated Cretaceous and Cenozoic sediments. Examples of Fall Zone features include the Potomac River's Little Falls and the rapids in Richmond, Virginia, where the James River falls across a series of rapids down to its own tidal estuary.

Before navigation improvements such as locks, the fall line was generally the head of navigation on rivers due to their rapids or waterfalls, and the necessary portage around them. Numerous cities initially formed along the fall line because of the easy river transportation to seaports, as well the availability of water power to operate mills and factories, thus bringing together river traffic and industrial labor. U.S. Route 1 and I-95 link many of the fall-line cities.

In 1808, Treasury Secretary Albert Gallatin noted the significance of the fall line as an obstacle to improved national communication and commerce between the Atlantic seaboard and the western river systems:[3]

The most prominent, though not perhaps the most insuperable obstacle in the navigation of the Atlantic rivers, consists in their lower falls, which are ascribed to a presumed continuous granite ridge, rising about one hundred and thirty feet above tide water. That ridge from New York to James River inclusively arrests the ascent of the tide; the falls of every river within that space being precisely at the head of the tide; pursuing thence southwardly a direction nearly parallel to the mountains, it recedes from the sea, leaving in each southern river an extent of good navigation between the tide and the falls. Other falls of less magnitude are found at the gaps of the Blue Ridge, through which the rivers have forced their passage...

Notable cities

Some cities that lie along the Piedmont–Coastal Plain fall line include the following (from north to south):

- Edison, New Jersey, and East Brunswick, New Jersey on the Raritan River

- Princeton, New Jersey, on the Millstone River

- Trenton, New Jersey, on the Delaware River.[2]

- Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on the Schuylkill River.[4]

- Wilmington, Delaware, on the Brandywine River.

- Perryville, Maryland, and Havre de Grace, Maryland, on the Susquehanna River/head of Chesapeake Bay.

- Baltimore, Maryland, on Herring Run, Jones Falls, and Gwynns Falls.[5]

- Elkridge, Maryland, on the Patapsco River.

- Laurel, Maryland, on the Patuxent River.

- Washington, D.C., on the Potomac River.[6]

- Occoquan, Virginia, on the Occoquan River.

- Fredericksburg, Virginia on the Rappahannock River.[6]

- Richmond, Virginia, on the James River.[7]

- Petersburg, Virginia, on the Appomattox River.[8]

- Weldon, North Carolina, and Roanoke Rapids, North Carolina, on the Roanoke River[9]

- Rocky Mount, North Carolina, on the Tar River.[9]

- Kinston, Smithfield, and Goldsboro, North Carolina, on the Neuse River.[9]

- Fayetteville, North Carolina, on the Cape Fear River.[9]

- Lumberton, North Carolina, on the Lumber River.[9]

- Cheraw, South Carolina, on the Pee Dee River.

- Camden, South Carolina, on the Wateree River.

- Columbia, South Carolina, on the Congaree River.[7]

- Augusta, Georgia, on the Savannah River.[10]

- Milledgeville, Georgia, on the Oconee River.[10]

- Macon, Georgia, on the Ocmulgee River.[10]

- Columbus, Georgia, on the Chattahoochee River.[2]

- Tallassee, Alabama, on the Tallapoosa River[11]

- Wetumpka, Alabama, on the Coosa River[11]

- Tuscaloosa, Alabama, on the Black Warrior River[11]

| State | Point (crossing) | Elevation & coordinates | Fall zone: drop/width (slope) |

Geomorphology Piedmont—Coastal plain |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| New Jersey | New Brunswick (Raritan River) | 460 ft (140 m) 40°29′18″N 74°26′52″W | ||

| Trenton (Delaware River) | 40°13′18″N 74°45′22″W | 8 ft | ||

| Pennsylvania | Philadelphia (Schuylkill River by I-76) | 39°57′13″N 75°10′17″W | ||

| Delaware | Wilmington (Brandywine Creek) | 39°44′42″N 75°32′54″W | ||

| Delaware | Newark (White Clay Creek) | 39°40′39″N 75°45′26″W | ||

| Maryland | Conowingo Dam (Susquehanna) | |||

| Ellicott City[12] (Patapsco) | 39°16.044′N 76°47.573′W | crystalline rock—unconsolidate marine sediments | ||

| Little Falls (Potomac River) | ||||

| Washington, DC | Theodore Roosevelt Island (Potomac River) | |||

| Virginia | Fredericksburg (Rappahannock) | 38°18.11′N 77°28.25′W | [west of Interstate 95 bridge][13] | |

| Emporia (Meherrin River)[14] | ||||

References

- "The Fall Line". A Tapestry of Time and Terrain: The Union of Two Maps - Geology and Topography. USGS.gov. Archived from the original on 2011-05-14. Retrieved 2010-08-12. An alternate source claims the southern endpoint is farther west because there are "waterfalls & rapids":

- "Georgia Geology". Archived from the original on 4 September 2010. Retrieved 2010-08-13.

- Freitag, Bob; Susan Bolton; Frank Westerlund; Julie Clark (2009). Floodplain Management: A New Approach for a New Era. Island Press. p. 77. ISBN 978-1-59726-635-2. Retrieved 17 November 2010.

- [Report on] Roads and Canals, Communicated to the Senate April 4, 1808, p.729

- Shamsi, Nayyar (2006). Encyclopaedia of Political Geography. Anmol Publications. pp. 92–93. ISBN 978-81-261-2406-0. Retrieved 17 November 2010.

- "Maryland Geology". Maryland Geological Society. Retrieved 25 January 2017.

- Deane, Winegar (2002). Highroad Guide to Chesapeake Bay. John F. Blair. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-89587-279-1. Retrieved 17 November 2010.

- Roberts, David C.; W. Grant Hodsdon (2001). Roger Tory Peterson (ed.). A Field Guide to Geology: Eastern North America. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 242. ISBN 978-0-618-16438-7. Retrieved 17 November 2010.

- "Geology of the Fall Line". Virginia Places. Retrieved 25 January 2017.

- "Fall Line". NCpedia. Retrieved 25 January 2017.

- "Fall Line". The New Georgia Encyclopedia. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- "Fall Line". Encyclopedia of Alabama. Retrieved 25 January 2017.

- "History/Culture". PatapscoHeritageGreenway.org. Archived from the original on 2010-03-10. Retrieved 2010-09-07.

George Ellicott House: A block away is the 1789 George Ellicott House at 24 Frederick Road., which has been saved, moved out of the flood plain, and restored. The Ellicott family settled here along the fall line of the Patapsco River in 1772 and built an innovative, water-powered flour mill

- "Fall Line". VirginiaPlaces.org. Retrieved 2010-08-13.

- "River and "Fall Line" Cities". VirginiaPlaces.org. Retrieved 2010-08-13.