Atomic diffusion

In chemical physics, atomic diffusion is a diffusion process whereby the random, thermally-activated movement of atoms in a solid results in the net transport of atoms. For example, helium atoms inside a balloon can diffuse through the wall of the balloon and escape, resulting in the balloon slowly deflating. Other air molecules (e.g. oxygen, nitrogen) have lower mobilities and thus diffuse more slowly through the balloon wall. There is a concentration gradient in the balloon wall, because the balloon was initially filled with helium, and thus there is plenty of helium on the inside, but there is relatively little helium on the outside (helium is not a major component of air). The rate of transport is governed by the diffusivity and the concentration gradient.

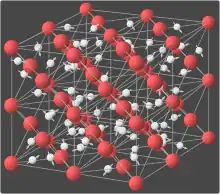

In crystals

In the crystal solid state, diffusion within the crystal lattice occurs by either interstitial or substitutional mechanisms and is referred to as lattice diffusion.[1] In interstitial lattice diffusion, a diffusant (such as C in an iron alloy), will diffuse in between the lattice structure of another crystalline element. In substitutional lattice diffusion (self-diffusion for example), the atom can only move by substituting place with another atom. Substitutional lattice diffusion is often contingent upon the availability of point vacancies throughout the crystal lattice. Diffusing particles migrate from point vacancy to point vacancy by the rapid, essentially random jumping about (jump diffusion).

Since the prevalence of point vacancies increases in accordance with the Arrhenius equation, the rate of crystal solid state diffusion increases with temperature.

For a single atom in a defect-free crystal, the movement can be described by the "random walk" model. In 3-dimensions it can be shown that after jumps of length the atom will have moved, on average, a distance of:

If the jump frequency is given by (in jumps per second) and time is given by , then is proportional to the square root of :

Diffusion in polycrystalline materials can involve short circuit diffusion mechanisms. For example, along the grain boundaries and certain crystalline defects such as dislocations there is more open space, thereby allowing for a lower activation energy for diffusion. Atomic diffusion in polycrystalline materials is therefore often modeled using an effective diffusion coefficient, which is a combination of lattice, and grain boundary diffusion coefficients. In general, surface diffusion occurs much faster than grain boundary diffusion, and grain boundary diffusion occurs much faster than lattice diffusion.

See also

References

- Heitjans, P.; Karger, J., eds. (2005). Diffusion in condensed matter: Methods, Materials, Models (2nd ed.). Birkhauser. ISBN 3-540-20043-6.