Atomic form factor

In physics, the atomic form factor, or atomic scattering factor, is a measure of the scattering amplitude of a wave by an isolated atom. The atomic form factor depends on the type of scattering, which in turn depends on the nature of the incident radiation, typically X-ray, electron or neutron. The common feature of all form factors is that they involve a Fourier transform of a spatial density distribution of the scattering object from real space to momentum space (also known as reciprocal space). For an object with spatial density distribution, , the form factor, , is defined as

- ,

where is the spatial density of the scatterer about its center of mass (), and is the momentum transfer. As a result of the nature of the Fourier transform, the broader the distribution of the scatterer in real space , the narrower the distribution of in ; i.e., the faster the decay of the form factor.

For crystals, atomic form factors are used to calculate the structure factor for a given Bragg peak of a crystal.

X-ray form factors

X-rays are scattered by the electron cloud of the atom and hence the scattering amplitude of X-rays increases with the atomic number, , of the atoms in a sample. As a result, X-rays are not very sensitive to light atoms, such as hydrogen and helium, and there is very little contrast between elements adjacent to each other in the periodic table. For X-ray scattering, in the above equation is the electron charge density about the nucleus, and the form factor the Fourier transform of this quantity. The assumption of a spherical distribution is usually good enough for X-ray crystallography.[1]

In general the X-ray form factor is complex but the imaginary components only become large near an absorption edge. Anomalous X-ray scattering makes use of the variation of the form factor close to an absorption edge to vary the scattering power of specific atoms in the sample by changing the energy of the incident x-rays hence enabling the extraction of more detailed structural information.

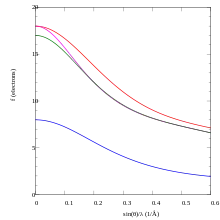

Atomic form factor patterns are often represented as a function of the magnitude of the scattering vector . Herein is the wavenumber and is the scattering angle between the incident x-ray beam and the detector measuring the scattered intensity, while is the wavelength of the X-rays. One interpretation of the scattering vector is that it is the resolution or yardstick with which the sample is observed. In the range of scattering vectors between Å−1, the atomic form factor is well approximated by a sum of Gaussians of the form

where the values of ai, bi, and c are tabulated here.[2]

Electron form factor

The relevant distribution, is the potential distribution of the atom, and the electron form factor is the Fourier transform of this.[3] The electron form factors are normally calculated from X-ray form factors using the Mott–Bethe formula.[4] This formula takes into account both elastic electron-cloud scattering and elastic nuclear scattering.

Neutron form factor

There are two distinct scattering interactions of neutrons by nuclei. Both are used in the investigation structure and dynamics of condensed matter: they are termed nuclear (sometimes also termed chemical) and magnetic scattering.

Nuclear scattering

Nuclear scattering of the free neutron by the nucleus is mediated by the strong nuclear force. The wavelength of thermal (several ångströms) and cold neutrons (up to tens of Angstroms) typically used for such investigations is 4-5 orders of magnitude larger than the dimension of the nucleus (femtometres). The free neutrons in a beam travel in a plane wave; for those that undergo nuclear scattering from a nucleus, the nucleus acts as a secondary point source, and radiates scattered neutrons as a spherical wave. (Although a quantum phenomenon, this can be visualized in simple classical terms by the Huygens–Fresnel principle.) In this case is the spatial density distribution of the nucleus, which is an infinitesimal point (delta function), with respect to the neutron wavelength. The delta function forms part of the Fermi pseudopotential, by which the free neutron and the nuclei interact. The Fourier transform of a delta function is unity; therefore, it is commonly said that neutrons "do not have a form factor;" i.e., the scattered amplitude, , is independent of .

Since the interaction is nuclear, each isotope has a different scattering amplitude. This Fourier transform is scaled by the amplitude of the spherical wave, which has dimensions of length. Hence, the amplitude of scattering that characterizes the interaction of a neutron with a given isotope is termed the scattering length, b. Neutron scattering lengths vary erratically between neighbouring elements in the periodic table and between isotopes of the same element. They may only be determined experimentally, since the theory of nuclear forces is not adequate to calculate or predict b from other properties of the nucleus.[5]

Magnetic scattering

Although neutral, neutrons also have a nuclear spin. They are a composite fermion and hence have an associated magnetic moment. In neutron scattering from condensed matter, magnetic scattering refers to the interaction of this moment with the magnetic moments arising from unpaired electrons in the outer orbitals of certain atoms. It is the spatial distribution of these unpaired electrons about the nucleus that is for magnetic scattering.

Since these orbitals are typically of a comparable size to the wavelength of the free neutrons, the resulting form factor resembles that of the X-ray form factor. However, this neutron-magnetic scattering is only from the outer electrons, rather than being heavily weighted by the core electrons, which is the case for X-ray scattering. Hence, in strong contrast to the case for nuclear scattering, the scattering object for magnetic scattering is far from a point source; it is still more diffuse than the effective size of the source for X-ray scattering, and the resulting Fourier transform (the magnetic form factor) decays more rapidly than the X-ray form factor.[6] Also, in contrast to nuclear scattering, the magnetic form factor is not isotope dependent, but is dependent on the oxidation state of the atom.

References

- McKie, D.; C. McKie (1992). Essentials of Crystallography. Blackwell Scientific Publications. ISBN 0-632-01574-8.

- "Atomic form factors". TU Graz. Retrieved 3 Jul 2018.

- Cowley, John M. (1981). Diffraction Physics. North-Holland Physics Publishing. pp. 78. ISBN 0-444-86121-1.

- De Graef, Marc (2003). Introduction to Conventional Transmission Electron Microscopy. Cambridge University Press. pp. 113. ISBN 0-521-62995-0.

- Squires, Gordon (1996). Introduction to the Theory of Thermal Neutron Scattering. Dover Publications. p. 260. ISBN 0-486-69447-X.

- Dobrzynski, L.; K. Blinowski (1994). Neutrons and Solid State Physics. Ellis Horwood Limited. ISBN 0-13-617192-3.

.svg.png.webp)