Attingham Park

| Attingham Park | |

|---|---|

The entrance front, Attingham Park | |

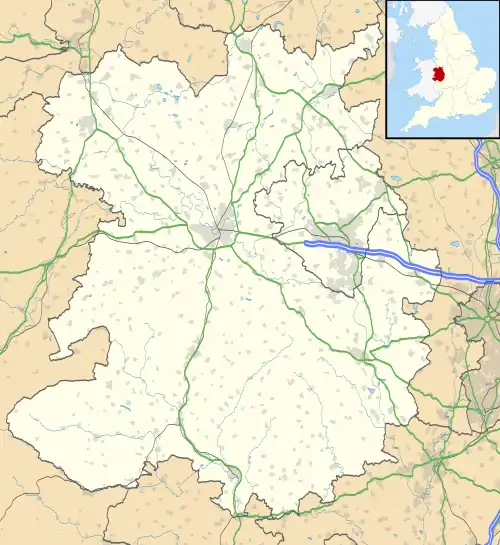

Attingham Park Location within Shropshire | |

| General information | |

| Type | Stately Home |

| Architectural style | Neoclassical |

| Location | near Atcham, Shropshire, England |

| Completed | Finished 1785 |

| Owner | National Trust |

| Website | |

| Official website | |

| References | |

Listed Building – Grade I | |

| Reference no. | 1055094[1] |

.JPG.webp)

Attingham Park /ˈætɪŋəm/ is an English country house and estate in Shropshire. Located near the village of Atcham, on the B4380 Shrewsbury to Wellington road. It is owned by the National Trust and is a Grade I listed building.

Attingham Park was built in 1785 for Noel Hill, 1st Baron Berwick, replacing a house on the site called Tern Hall. With money he inherited, along with his title, he commissioned the architect George Steuart to design a new and grander house to be built around the original hall. The new country house encapsulated the old property entirely, and once completed it was given the new name 'Attingham Hall'.

The Estate comprises roughly 4,000 acres (1,600 ha), and the extensive 640 acres (260 ha) of parkland and gardens of Attingham have a Grade II* Listed status. Over 560,000 people visited in 2022/23, placing it as the most popular National Trust property.

Across the parkland there are five Grade II* listed buildings, including the stable block, the Tern Lodge toll house which can be seen on the B4380, and two bridges that span the River Tern. There are also 12 Grade II listed structures including the retaining walls of the estate, the bee house, the ice house, the walled garden, the ha-ha, which can be seen in the front of the mansion, and the Home Farm.

History

Pre-history, Roman and Early Medieval

The archaeology of Attingham Park is diverse covering many different periods of history and human habitation. People have lived around the area of the estate for around 4,000 years since the Bronze Age, utilising the rich alluvial soils for agriculture. There are seven scheduled ancient monuments across the wider estate including an Iron Age settlement, Roman forts and a significant portion of the fourth largest civitas in Roman Britain, Viroconium, on the site of the nearby village of Wroxeter.[2]

There are also the archeological remains of Saxon palaces.,[3]

By the mediaeval period, a village Berwick Maviston is recorded. This has not survived, but today the remains of a moat and fish ponds from the old manor can still be seen. The manor and the village dated back to the Norman invasion, being mentioned in the 1086 Domesday book.

This original manor fell into disrepair in mediaeval times. It was replaced with another house known as 'Grant's Mansion' was recorded on the site in 1790.

This village was occupied until the 1780s when the newly created Baron Berwick built Attingham and removed the village from his land. The title of Baron Berwick comes from the name of this village.[4]

The arrival of the Hill family

_School_-_Sir_Rowland_Hill_(1492%E2%80%931561)_-_1298284_-_National_Trust.jpg.webp)

The associations of the Hill family with the area of the Park can be traced to a civic benefaction of the tudor statesman Sir Rowland Hill of Soulton, convenor of the Geneva Bible translation, who built the first stone bridge over the river here:[5] this was part of his wider civic projects across London and Shropshire and a portrait of him is still displayed in the mansion.[6] Multiple monuments have been erected to him, in which he is holding Magna Carta.

_School_-_The_Reverend_and_Right_Honourable_Richard_Hill_of_Hawkstone_(1654%E2%80%931727)_-_1298214_-_National_Trust.jpg.webp)

Prior to the construction of the current mansion, a building called Tern Hall existed on the site which had been built to his own designs by a relative of Richard Hill of Hawkstone, a relative of 'Old Sir Rowland'.[7][8]

The Hills, Barons of Berwick

Attingham, including Cronkhill, was the seat of the Barons Berwick from the 1780s until that title became extinct in 1953. On the death of Thomas Henry Noel-Hill, 8th Baron Berwick (1877–1947), who died childless, the Attingham Estate, comprising the mansion and some 4,000 acres (1,600 ha), was gifted to the National Trust.[9][10] Attingham Park was designed by George Steuart, a follower of James Wyatt and encapsulated Tern Hall. It is the only remaining example of a country house by Steuart; he later designed St Chad's Church, Shrewsbury.[7] It was built from 1782 to 1785 for Noel Hill, 1st Baron Berwick. Lord Berwick, a former MP for Shropshire, received his title in 1784 during the premiership of William Pitt the Younger, during which he had been instrumental in the reorganisation of the East India Company.[8] The proportions have been criticised: for Simon Jenkins "The façade is uncomfortably tall, almost barracks-like, the portico columns painfully thin".[7] There is a large entrance court, with an imposing gatehouse, and two single storey wings stretch out to either side of the main block. The main reception rooms were divided into a male and female set on either side of the house.

In 1789, the 1st Lord Berwick died, and his son, Thomas Noel Hill, 2nd Baron Berwick, succeeded him. Thomas was a collector and patron of the arts, who commissioned improvements to the house and extensions of the estate.[11] This included commissioning John Nash in 1805 to add the picture gallery, a project that was flawed from the beginning as it suffered from leaks. Constructed using cast iron and curved glass to give the effect of coving, it throws light into the gallery below.[12] In 2013 work began on building a new protective roof above the delicate Nash roof, replacing one installed in the 1970s with a new one which will stop leakage and reduce natural weather wear. The new roof has temperature control, blinds, and UV resistant glass.[13]

The 2nd Lord Berwick reached financial ruin, and all the contents of the house were auctioned in 1827 and in 1829; some were purchased by his two brothers.[7] He died in Italy in 1832, and his brother, William Noel-Hill, 3rd Baron Berwick inherited the estate.[11] William was a diplomat, who was posted in Italy for 28 years; described by Lord Byron as 'the only one of the diplomatists whom I ever knew who really is Excellent’, his collection of Italian art and furniture became part of Attingham's collection upon his inheritance. This included the tableware by silversmith Paul Storr.[14] William died in 1832, and his younger brother, Richard Noel-Hill, 4th Baron Berwick inherited; as the youngest son and a clergyman, he had not expected to inherit. His son, Richard Noel Noel-Hill, 5th Baron Berwick, inherited in 1848, and was a careful steward, introducing agricultural modernisations and clearing many of the estate's debts that had been accrued by his father and uncles.[15] He lived at Cronkhill on the estate and whilst there invented to eponymous Cronkhill rifle.[16]

Richard was succeeded by his brother, William Noel-Hill, 6th Baron Berwick, in 1861, who was a colonel in the army, and chose to not live at Attingham. William died in 1882 and his nephew Richard Henry Noel-Hill, 7th Baron Berwick, inherited the estate. The 7th Baron had financial problems and sold family heirlooms to pay off debts.[15] He died in 1897.

20th century

Thomas Henry Noel-Hill, 8th Baron Berwick (nephew of the 7th baron) inherited the estate. A diplomat, who worked in France, he added French decorative arts to the Attingham collection. He also had electricity installed in the house, and made improvements to the estate.[17]

During the First World War, Attingham was owned by the 8th Lord Berwick who let the property to the Dutch-American Van Bergen family who encouraged the establishment of a hospital for wounded soldiers at Attingham. The hospital opened in October 1914 and by 1918 had 60 beds and an operating theatre. During the War, the 8th Lord Berwick served with the Shropshire Yeomanry and as a diplomat in Paris. Throughout the war years he corresponded with Teresa Hulton, whom he married in June 1919. During the war, Teresa Hulton had worked with Belgian refugees in London and as a Red Cross nurse in Italy.[19] The couple dedicated themselves to the renovation of the house, with Hulton taking on responsibility for the conservation of historic textiles.[20] During the Second World War, Edgbaston Church of England Girls’ School was evacuated and lived in part of the house; it later hosted the Women's Auxiliary Air Force.[17]

Transfer to the National Trust

In 1937, negotiations started with the National Trust, and it was donated to them in 1947 as a bequest in the will of the 8th Lord Berwick. His wishes stated that the house and estate should be curated as "a good example of Eighteenth Century Architecture with such contents in the principal rooms as a nobleman of that period would have had".[9]

Management under the National Trust

Attingham Trust and country house studies

Between 1948 and 1976, the Shropshire Adult Education College occupied the hall, run by Sir George Trevelyan.

In 1952 the Attingham Trust was set up by George Trevelyan and Helen Lowenthal, the purpose of the Attingham Trust being to offer American curators the opportunity to learn about British country houses. A summer school has been run by the Attingham Trust every year since 1952 and now takes in a diverse array of country houses around the United Kingdom including some National Trust properties. The Attingham name has since been used worldwide with the American Friends of the Attingham Trust being founded in 1962 in New York City, and the Attingham Society being founded in 1985. The Attingham Society covers the whole world and alongside the American Friends its purpose is to keep its members in touch and the continued education and interest of British country houses.[21]

Restoration and conservation

Until the 1990s, most of Attingham was closed to the public and visitors could only enter a small number of rooms. From 2000 to 2016, the National Trust ran a research and conservation programme entitled Attingham Re-discovered, where conservators worked in view of the public and rooms were re-displayed. Major projects as part of the restoration included replacement of the Picture Gallery's carpet, and the replacement of a secondary roof in 2012.[22] In 2014 visitors were invited to participate in identifying outstanding conservation needs in the house.[23][24]

Attingham is a National Trust regional hub for Herefordshire, Shropshire and Staffordshire.[25]

Estate buildings

The estate has a walled garden and an orchard, which grows fresh produce which is used on the estate in the tearooms, and sold to visitors. The walled garden is a rare Georgian survival; a restoration programme began in the 1990s, which led to a return to cultivation of 25% of the garden by 2008. The orchard contains 37 varieties of fruit trees.[26]

Attingham is also the location of one of the two surviving Regency bee houses in the country.[27] The Attingham bee house dates to 1805, has a slate roof to keep the hives dry, and lattice work to enable bees to freely fly in and out.[28]

Attingham's Stables were purpose-built at the same time as the house for the first Lord Berwick. Designed by Steuart, they have pyramidal ornamentation and were purposefully sited on the approach to the house, as a demonstration of taste and wealth.[29]

Parkland

The Estate comprises roughly 4,000 acres (1,600 ha), but during the early 1800s extended to twice that amount at 8,000 acres (3,200 ha).[30] The extensive 640 acres (260 ha) of parkland and gardens at Attingham have a Grade II* Listed status.

The park was landscaped by Humphry Repton and includes woodlands and a deer park. As of 2018, around 180 fallow deer lived in the park, with number maintained through an annual cull.[31]

The River Tern, which flows through the centre of the estate, joins the larger River Severn at the confluence just south of the Tern Bridge.[32] The rivers were also used by the estate, with ironworks on the Tern that enhanced family fortune in the 1700s.[33] Fish from the rivers were an important resource, both for food and for recreation.[34]

The park is a designated Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) due to it being home to many rare species of invertebrates. There are seven units of SSSI around the park totalling to 470 acres (190 ha), nearly three-quarters of the entire estate. The amount of deadwood left by fallen trees around the parkland makes it the perfect habitat for a variety of different species, primarily beetles. Several of these beetle species are adapted to the ecology of ancient trees, including the flat bark beetle, Notolaemus unifasciatus, and the silken fungus beetle, Atomaria barani.[35] In 2005 a survey of the flora of the park was undertaken by Shropshire Botanical Society, which identified 68 species in the park, that had not been recorded on the last survey undertaken 1969-72. Drainage of the site had an impact on several species, with the loss of Alopecurus aequalis, Rumex maritimus and Veronica scutellata, as well as the additions of dry heathland species such as Veronica officinalis and Ulex europaeus.[36]

Cronkhill

The nearby Italianate villa of Cronkhill on the estate is an important pioneer of this style in England and was designed by the architect, John Nash. It was designed for the 2nd Lord Berwick, around the same time as the Picture Gallery, and the first person to live in it was his land agent, Francis Walford.[37] Cronkhill is located on the wider estate, on a hillside overlooking the River Severn valley and the Wrekin hill. The villa is owned by the National Trust and is privately tenanted. It is open to visitors a few days of the year.[38]

See also

The other major Hill houses at:

as well as:

References

Bibliography

- Douglas, Sarah (2018). Attingham: A story of love and neglect. The History Press/National Trust. ISBN 978-1-84359-361-4.

- Jenkins, Simon, England's Thousand Best Houses, 2003, Allen Lane, ISBN 0-7139-9596-3

Footnotes

- Historic England. "Attingham Park (1055094)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 1 September 2013.

- Douglas, p.38

- Neal, Toby. "Rare Saxon hall find at Attingham excites the experts". www.shropshirestar.com. Retrieved 17 April 2023.

- Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1020281)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- Camden, Theophilus (1813). The History of the Present War in Spain and Portugal: From Its Commencement to the Battle of Vittoria ... : to which Will be Added, Memoirs of the Life of Lord Wellington ... W. Stratford.

- Trigg, Keri. "Portrait of the past is restored at Attingham Park". www.shropshirestar.com. Retrieved 16 April 2023.

- Jenkins, 638

- Douglas, p.4

- Douglas, p.13

- "The wider Attingham Estate". National Trust. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- Douglas, p.6

- Douglas, p.50

- "Attingham Park restoration work starts". BBC News. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- Douglas, 8-9

- Douglas, 10-11

- Williams, Gareth (2021). The Country Houses of Shropshire. Boydell & Brewer. p. 201. ISBN 978-1-78327-539-7.

- Douglas, 12-13

- Eveleigh, David (16 September 2011). A History of the Kitchen. The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-7055-9.

- "Attingham WWI Stories". Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- Ponsonby, Margaret (15 April 2016). Faded and Threadbare Historic Textiles and their Role in Houses Open to the Public. Routledge. p. 143. ISBN 978-1-317-13690-3.

- "The Attingham Trust: About us". The Attingham Trust. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- Douglas, p.48-50

- Dillon, C.; Golfomitsou, S.; Storey, C.; Lithgow, K. (4 March 2019). "A clear view: crowdsourcing conservation needs in historic houses using visitor-led photo surveys". Museum Management and Curatorship. 34 (2): 144–165. doi:10.1080/09647775.2018.1520642. ISSN 0964-7775. S2CID 149798868.

- Dillon, C. A. T. H. E. R. I. N. E., et al. "Bottom‑up and Mixed‑Methods Approach to Understanding Visi‑tors’ Perceptions of Dust, Dirt and Cleaning." ICOM‑CC 18th Triennial Conference Preprints (Copenhagen, 2017). Paris: International Council of Museums. 2017.

- "Regional contact details". National Trust. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- Douglas, p.32

- Douglas, p.27

- Foy, Karen (30 September 2014). Life in the Victorian Kitchen: Culinary Secrets and Servants' Stories. Pen and Sword. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-78303-639-4.

- Newman, John; Pevsner, Nikolaus; Watson, Gavin (1 January 2006). Shropshire. Yale University Press. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-300-12083-7.

- Douglas, p.40

- Douglas, p.44

- Black, Jeremy (2021). England in the Age of Austen. Indiana University Press. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-253-05194-3.

- Rowley, Trevor (1986). The Landscape of the Welsh Marches. M. Joseph. ISBN 978-0-7181-2347-5.

- Douglas, p.41

- "Site of Special Scientific Interest information" (PDF). Natural England. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 March 2017. Retrieved 14 March 2017.

- Whild, Sarah, et al. "New Flora of Attingham Park." (2005).

- "A generous gesture for a friend" according to the National Trust; other sources imply that Walford was Nash's patron in this project.

- "Attingham Park Estate Cronkhill". National Trust. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

External links

- Attingham Park information at the National Trust

- BBC website panoramic view of Attingham Park and House

- www.geograph.co.uk : photos of Attingham Park and surrounding area today

- http://attinghamww1stories.wordpress.com/ : a blog telling the story of Attingham Park during the First World War

- http://attinghamparkmansion.wordpress.com/

- Wikidata list of paintings on view at Attingham