Austronesian vessels

The Austronesian vessels, are those devised or used by the Austronesian peoples of Taiwan, Maritime Southeast Asia, Micronesia, coastal New Guinea, Island Melanesia, Polynesia, and Madagascar that speak Austronesian languages.[2] They also include indigenous ethnic minorities in Vietnam, Cambodia, Myanmar, Thailand, Hainan, the Comoros, and the Torres Strait Islands. The vessels have carried trade and migration across long distances in the region. They include monohulls, catamarans, outriggers, and proas. Sail types include a variety of crab-claw and tanja configurations.

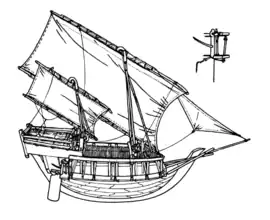

Traditional Austronesian generalized sail types. C, D, E, and F are types of crab claw sails. G, H, and I are tanja sails.[1]

Traditional Austronesian generalized sail types. C, D, E, and F are types of crab claw sails. G, H, and I are tanja sails.[1]

A Double sprit (Sri Lanka)

B Common sprit (Philippines)

C Oceanic sprit (Tahiti)

D Oceanic sprit (Marquesas)

E Oceanic sprit (Philippines)

F Crane sprit (Marshall Islands)

G Rectangular boom lug (Maluku Islands)

H Square boom lug (Gulf of Thailand)

I Trapezial boom lug (Vietnam)

Sea-faring tradition

The seafaring Austronesian peoples independently developed various sail types during the Neolithic, beginning with the crab claw sail (also misleadingly called the "oceanic lateen" or the "oceanic sprit") at around 1500 BCE. They are used throughout the range of the Austronesian Expansion, from Maritime Southeast Asia, to Micronesia, Island Melanesia, Polynesia, and Madagascar. Crab claw sails are rigged fore-and-aft and can be tilted and rotated relative to the wind. They evolved from "V"-shaped perpendicular square sails in which the two spars converge at the base of the hull. The simplest form of the crab claw sail (also with the widest distribution) is composed of a triangular sail supported by two light spars (sometimes erroneously called "sprits") on each side. They were originally mastless, and the entire assembly was taken down when the sails were lowered.[3]

Hull configurations

Austronesian rigs were used for double-canoe (catamaran), single-outrigger (on the windward side), or double-outrigger boat configurations, in addition to monohulls.[4][5] There are several distinct types of crab claw rigs, but unlike western rigs, they do not have fixed conventional names.[6]

The need to propel larger and more heavily laden boats led to the increase in vertical sail. However this introduced more instability to the vessels. In addition to the unique invention of outriggers to solve this, the sails were also leaned backwards and the converging point moved further forward on the hull. This new configuration required a loose "prop" in the middle of the hull to hold the spars up, as well as rope supports on the windward side. This allowed more sail area (and thus more power) while keeping the center of effort low and thus making the boats more stable. The prop was later converted into fixed or removable canted masts where the spars of the sails were actually suspended by a halyard from the masthead. This type of sail is most refined in Micronesian proas which could reach very high speeds. These configurations are sometimes known as the "crane sprit" or the "crane spritsail". Micronesian, Island Melanesian, and Polynesian single-outrigger vessels also used this canted mast configuration to uniquely develop shunting, where canoes are symmetrical from front to back and change end-to-end when sailing against the wind.[3][6]

The conversion of the prop to a fixed mast led to the much later invention of the tanja sail (also known variously and misleadingly as the canted square sail, canted rectangular sail, boomed lugsail, or balance lugsail). Tanja sails were rigged similarly to crab claw sails and also had spars on both the head and the foot of the sails; but they were square or rectangular with the spars not converging into a point.[3][6]

Another evolution of the basic crab claw sail is the conversion of the upper spar into a fixed mast. In Polynesia, this gave the sail more height while also making it narrower, giving it a shape reminiscent of crab pincers (hence "crab claw" sail). This was also usually accompanied by the lower spar becoming more curved.[3][6]

Melanesian V-shaped square sail

Melanesian V-shaped square sail New Zealand V-shaped square sail

New Zealand V-shaped square sail

Hawaiian crab claw sail with the upper spar merged with the fixed mast

Hawaiian crab claw sail with the upper spar merged with the fixed mast

Proa

The vessel known as the "proa" (or more accurately the "Pacific proa") in western terminology is more accurately a single-outrigger Austronesian boat with one sail (typified by vessels like the Chamorro sakman). Both ends are alike, and the boat is sailed in either direction, but it has a fixed leeward side and a windward side. The boat is shunted from beam reach to beam reach to change direction, with the wind over the side, a low-force procedure. The bottom corner of the crabclaw sail is moved to the other end, which becomes the bow as the boat sets off back the way it came. The mast usually hinges, adjusting its rake (mast). The proa is a low-stress rig, which can be built with simple tools and low-tech materials, but it is extremely fast. On a beam reach, it may be the fastest simple rig.

In a traditional Pacific proa, the outrigger (ama) lies on the windward side of the main hull (vaka), with its weight helping keep the proa upright. The ama is very thin, to punch through waves, smoothing the ride. The first Europeans, building proas from travelers' reports, built Atlantic proas, with the outrigger on the leeward side, with its buoyancy keeping the proa upright.

"To be clear, we can blame Richard C. Newick for the debate" (about racing proas), "since it was he who came up with the Atlantic proa in the first place, with his groundbreaking Cheers — the “giant killer” that came in third in the 1968 OSTAR. Unlike all proas until Cheers, Newick placed the ama to lee and the rig to windward, concentrating all the ballast to windward and thus multiplying the righting moment."[7]

The term "proa" was also historically used for other types of Austronesian vessels with different rigs, with or without outriggers.

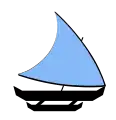

Pacific proa, on a beam reach rightwards, with the wind blowing into the page.

Pacific proa, on a beam reach rightwards, with the wind blowing into the page. Atlantic proa. Note that the wind is on the other side, blowing out of the page.

Atlantic proa. Note that the wind is on the other side, blowing out of the page.

See also

References

- Doran, Edwin B. (1981). Wangka: Austronesian Canoe Origins. Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 9780890961070.

- Pierron, Denis; Razafindrazaka, Harilanto; Pagani, Luca; Ricaut, François-Xavier; Antao, Tiago; Capredon, Mélanie; Sambo, Clément; Radimilahy, Chantal; Rakotoarisoa, Jean-Aimé; Blench, Roger M.; Letellier, Thierry (2014-01-21). "Genome-wide evidence of Austronesian–Bantu admixture and cultural reversion in a hunter-gatherer group of Madagascar". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111 (3): 936–941. Bibcode:2014PNAS..111..936P. doi:10.1073/pnas.1321860111. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 3903192. PMID 24395773.

- Campbell, I.C. (1995). "The Lateen Sail in World History". Journal of World History. 6 (1): 1–23. JSTOR 20078617.

- Horridge A (2008). "Origins and Relationships of Pacific Canoes and Rigs" (PDF). In Di Piazza A, Pearthree E (eds.). Canoes of the Grand Ocean. BAR International Series 1802. Archaeopress. ISBN 9781407302898. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 22 October 2019.

- Lacsina, Ligaya (2016). Examining pre-colonial Southeast Asian boatbuilding: An archaeological study of the Butuan Boats and the use of edge-joined planking in local and regional construction techniques (PhD). Flinders University.

- Horridge, Adrian (April 1986). "The Evolution of Pacific Canoe Rigs". The Journal of Pacific History. 21 (2): 83–99. doi:10.1080/00223348608572530. JSTOR 25168892.

- "Proa File – Discussion Forum". ProaFile.com. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

_-_Lakatoi%252C_Near_Elevala_Island.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)