Awjila

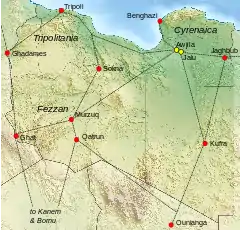

Awjila (Berber: Awilan, Awjila, Awgila; Arabic: أوجلة; Latin: Augila) is an oasis town in the Al Wahat District in the Cyrenaica region of northeastern Libya. Since classical times it has been known as a place where high quality dates are farmed. From the Arab conquest in the 7th century, Islam has played an important role in the community. The oasis is located on the east-west caravan route between Egypt and Tripoli, Libya, and on the north-south route between Benghazi and the Sahel between Lake Chad and Darfur, and in the past was an important trading center. It is the place after which the Awjila language, an Eastern Berber language, is named. The people cultivate small gardens using water from deep wells. Recently, the oil industry has become an increasingly important source of employment.

Awjila

أوجله Awilan / ⴰⵡⵉⵍⴰⵏ | |

|---|---|

Town | |

A farm in Awjilah | |

Awjila Location in Libya | |

| Coordinates: 29°6′29″N 21°17′13″E | |

| Country | |

| Region | Cyrenaica |

| District | Al Wahat |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| License Plate Code | 67 |

Location

Awjila and the adjoining oasis of Jalu are isolated, the only towns on the desert highway between Ajdabiya, 250 kilometres (160 mi) to the northwest, and Kufra, 625 kilometres (388 mi) to the southeast.[1] An 1872 account describes the cluster of three oases: the Aujilah oasis, Jalloo (Jalu) to the east and Leshkerreh (Jikharra) to the northeast. Each oasis had a small hill covered in date palm trees, surrounded by a plain of red sand impregnated with salts of soda.[2] Between them these oases had a population of 9,000 to 10,000 people.[2] The people of the oasis are mainly Berber, and some still speak a Berber-origin language.[3] As of 2005 the Awjila language was highly endangered.[4]

Climate

| Climate data for Awjila | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 19.9 (67.8) |

21.9 (71.4) |

25.3 (77.5) |

29.7 (85.5) |

34.7 (94.5) |

37.2 (99.0) |

36.7 (98.1) |

36.9 (98.4) |

35.8 (96.4) |

32.4 (90.3) |

27.0 (80.6) |

21.4 (70.5) |

29.9 (85.8) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 5.6 (42.1) |

7.0 (44.6) |

9.2 (48.6) |

13.1 (55.6) |

18.3 (64.9) |

19.9 (67.8) |

21.0 (69.8) |

21.0 (69.8) |

19.9 (67.8) |

16.3 (61.3) |

12.0 (53.6) |

7.7 (45.9) |

14.3 (57.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 3 (0.1) |

3 (0.1) |

3 (0.1) |

2 (0.1) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

3 (0.1) |

2 (0.1) |

3 (0.1) |

19 (0.7) |

| Source: Climate-data.org | |||||||||||||

History

Classical times

The Awjila (Augila) oasis is mentioned by Herodotus (c. 484 – 425 BC). He describes the nomadic Nasamones who migrated between the coasts of Syrtis Major and the Augila oasis, where they may have exacted tribute from the local people.[5] Herodotus says it was a journey of ten days from the oasis of Ammonium, modern Siwa, to the oasis of Augila. This distance was confirmed by the German explorer Friedrich Hornemann (1772–1801), who covered the distance in nine days, although caravans normally take 13 days. In the summer the Nasamones left their flocks by the coast and travelled to the oasis to gather dates. There were other permanent inhabitants of the oasis.[2]

Ptolemy (c. 90 – 168) implies that the Greek colonists had forced the Nasamones to leave the coast and take up residence in Augila.[2] Procopius, writing around 562, says that even in his day sacrifices continued to be made to Ammon and to Alexander the Great of Macedon in two Libyan cities that were both called Augila. He was probably referring to what are now El Agheila on the Gulf of Sirte and the oasis of Awjilah. According to Procopius the temples of the oasis were converted into Christian churches by the Byzantine Emperor Justinian I (c. 482 – 565).[2] The 6th-century geographer Stephanus of Byzantium described Augila as a city.[2]

Early Arab era

The Arabs launched a campaign against the Byzantine Empire soon after the Prophet Muhammad died in 632, quickly conquering Syria, Persia and Egypt. After occupying Alexandria in 643, they swept along the Mediterranean coast of Africa, taking Cyrenaica in 644, Tripolitania in 646 and Fezzan in 663.[6]

The region around Awjila was conquered by Sidi ‘Abdullāh ibn Sa‘ad ibn Abī as-Sarḥ.[7] He was the Prophet's companion and standard bearer, and an important saint. His tomb was established in Awjila around 650.[8] A modern structure has since replaced the original tomb.[1] The Sarahna family, who consider themselves the family of Sidi Abdullah, are the protectors of his tomb. When the Senussi center was established in Awjila in 1872, the Sarahna assumed the role of Islamic teachers.[9]

After being introduced in the 7th century, Islam has always been a major influence on the life of the oasis. The Arab chronicler Al-Bakri says that there were already several mosques around the oasis by the 11th century.[10] According to oral tradition, in the 12th century a learned man from the coast of Tripolitania said that there were forty shrines in Awjila, and forty saints hidden among the people of the oasis. By the late 1960s only sixteen shrines remained.[10] Some of the saints in the surviving tombs lived during the early years of Islam, and the details of their life and even their family lineage have been forgotten.[8]

Trading centre

In the 10th century Awjila was a stage on the trading route between the Ibadi Berber capital of Zuwayla[lower-alpha 1] in the Fezzan and the newly established Fatimid capital of Cairo in Egypt.[11] The east-west caravan route from Cairo to Tripoli, the Fezzan and Tunis went via Jaghbub, Jalu and Awjila.[12] In the early Mamluk era (13th century), trade from Egypt was along a route that led via Awjila to the Fezzan, and then on to Kanem, Bornu and to cities such as Timbuktu on the Niger bend. Awjila became the main market for slaves from these regions.[13] Most of these slaves supplied domestic needs.[14] Gold was purchased from Bambouk and Bouré in what is now Senegal but then was part of the Mali Empire of the Mandinka people. In exchange, Egypt exported textiles.[13]

During the Ottoman period in Egypt, Awjila lay on the route taken by pilgrims traveling from Timbuktu via Ghat, Ghadames and the Fezzan, avoiding the main Ottoman centers.[15] In 1639 Awjila came under the rule of the Turkish ruler of Tripolitania, who stationed a permanent garrison at Benghazi.[16] In the 18th century, the merchants of Awjila held a monopoly over the trade between Cairo and the Fezzan.[17] Describing the trade between Egypt and Hausaland, Hornemann lists:

... slaves of both sexes, ostrich feathers, zibette (musk from civet cats), tiger skins (sic), and gold, partly in dust, partly in native grains, to be manufactured into rings and other ornaments for the people of interior Africa. From Bornu, copper is imported in great quantity. Cairo sends silks, melayes (striped blue and white calicoes - i.e. milayat, wrappers, sheeting) woolen cloths, glass... beads for bracelets, and an... assortment of East India goods... The merchants of Bengasi usually join the caravan from Cairo at Augila, import tobacco manufactured for chewing, or snuff, and sundry wares fabricated in Turkey...[18]

Around 1810 a Majabra trader from Jalu named Schehaymah became lost while travelling to Wadai via Murzuk in the Fezzan. He was found by some Bidayat, who took him via Ounianga to Wara, the old capital of Wadai. The Sultan of Wadai, Abd al-Karim Sabun (1804–1815) agreed with Schehaymah's proposal to open a caravan route to Benghazi along a direct route through Kufra, and Awjila / Jalu. This new route would bypass both Fezzan and Darfur, states that until then had controlled the eastern Saharan trade. The first caravans travelled the route between 1809 and 1820.[19]

The trade was disrupted for a while in the 1820s due to political instability in Wadai, but starting in the 1830s every two or three years a caravan would travel the route. Usually there were two or three hundred camels carrying ivory and skins, along with a batch of slaves.[20] Trade increased from the 1860s. The main stations between Benghazi and the southern terminal at Abéché were the assembly point at Awjila / Jalu where the caravans were made up, and the center at Kufra where food and water could be obtained.[21] Later the north-south route again grew in importance due to disruption of traffic on the Nile by the Mahdist revolution in the Sudan.[19]

Muhammad ibn Ali as-Senussi stayed in Jalu and Awjila before opening his first lodge in al-Baida in 1843. Over the next ten years the lodges of the Senussi became established throughout the Bedouins of Cyrenaica.[22] Later they spread the Senussi influence further south, helping quell violence and resolve trade disputes.[23] Each post on the north-south route, including Awjila, was protected by a Senussi sheikh.[19] As late as 1907, a significant amount of the trade passing through Benghazi was in goods carried over this route, and goods would also have been routed from interior points such as Awjila and Jalu east to Egypt and west to Tripoli.[24]

Recent years

Today the main activities of the people in Awjila are agriculture and working for the oil sector companies, as this area is the cradle of Libyan wealth. The main crops are dates from the many varieties of palm trees, tomatoes, and cereals. The Awjila oasis is known for the high quality of its dates.[7] Starting in the 1960s, the oil industry drove growth in the once-sleepy village.[25] In 1968 the population of the village was about 2,000 people, but by 1982 it had risen to over 4,000, supported by twelve mosques.[26] A 2007 travel guide gives the population as 6,790.[27]

The Great Mosque of Atiq is the oldest masjed (mosque) in the Sahara with its unique style of architecture with rooms that are naturally air conditioned. In the scorching heat of the summer days the rooms are cool and at night they are warm.[28] The oasis was a destination for viewing the Solar eclipse of March 29, 2006.[29]

References

Notes

- The medieval gate of Bab Zuweila in Cairo takes its name from Zuwayla.[11]

Citations

- Ham 2007, p. 132.

- Smith 1872, p. 338.

- Chandra 1986, p. 113.

- Batibo 2005, p. 77.

- Asheri et al. 2007, p. 698.

- Falola, Morgan & Oyeniyi 2012, p. 14.

- Awjila: Libyan Tourism.

- Mason 1974, p. 396.

- Mason 1974, p. 397.

- Mason 1974, p. 395.

- Martin 1983, p. 555.

- Fage & Oliver 1985, p. 16.

- Oliver & Atmore 2001, p. 19.

- Oliver & Atmore 2001, p. 20.

- Oliver & Atmore 2001, p. 46.

- Holt, Lambton & Lewis 1977, p. 263.

- Walz 1975, p. 665.

- Martin 1983, p. 567.

- Cordell 1977, p. 22.

- Cordell 1977, p. 23-24.

- Cordell 1977, p. 24.

- Cordell 1977, p. 28.

- Cordell 1977, p. 29.

- Cordell 1977, p. 21.

- Mason 1982, p. 323.

- Mason 1982, p. 322.

- Ham 2007, p. 131.

- Awjila: MVM Travel.

- Atiq Mosque: Atlas Obscura.

Sources

- Asheri, David; Lloyd, Alan Brian; Corcella, Aldo; Murray, Oswyn; Graziosi, Barbara (2007). A Commentary on Herodotus. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-814956-9. Retrieved 2013-03-24.

- "Atiq Mosque: Early Islamic mosque with several strange conical domes". Atlasobscura.com. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

- "Awjila". Libyan Tourism Directory. Archived from the original on 2013-04-11. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- "Awjila". MVM Travel. Retrieved 2012-03-24.

- Batibo, Herman (2005). Language Decline And Death In Africa: Causes, Consequences And Challenges. Multilingual Matters. ISBN 978-1-85359-808-1. Retrieved 2013-03-24.

- Chandra, Satish (1986). International Protection of Minorities. Mittal Publications. GGKEY:L2U7JG58SWT. Retrieved 2013-03-24.

- Cordell, Dennis D. (January 1977). "Eastern Libya, Wadai and the Sanūsīya: A Tarīqa and a Trade Route". The Journal of African History. Cambridge University Press. 18 (1): 21–36. doi:10.1017/s0021853700015218. JSTOR 180415.

- Fage, John Donnelly; Oliver, Roland Anthony (1985). The Cambridge History of Africa. Vol. 6. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-22803-9. Retrieved 2013-03-27.

- Falola, Toyin; Morgan, Jason; Oyeniyi, Bukola Adeyemi (2012). Culture and Customs of Libya. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-37859-1. Retrieved 2013-03-24.

- Ham, Anthony (1 August 2007). Libya. Ediz. Inglese. Lonely Planet. p. 132. ISBN 978-1-74059-493-6. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

- Holt, Peter M.; Lambton, Ann K. S.; Lewis, Bernard (1977-04-21). The Cambridge History of Islam. Vol. 2A. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29137-8. Retrieved 2013-03-27.

- Martin, B. G. (December 1983). "Ahmad Rasim Pasha and the Suppression of the Fazzan Slave Trade, 1881-1896". Africa: Rivista trimestrale di studi e documentazione dell'Istituto italiano per l'Africa e l'Oriente. Istituto Italiano per l'Africa e l'Oriente (IsIAO). 38 (4): 545–579. JSTOR 40759666.

- Mason, John Paul (October 1974). "Saharan Saints: Sacred Symbols or Empty Forms?". Anthropological Quarterly. The George Washington University Institute for Ethnographic Research. 47 (4): 390–405. doi:10.2307/3316606. JSTOR 3316606.

- Mason, John P. (Summer 1982). "Qadhdhafi's "Revolution" and Change in a Libyan Oasis Community". Middle East Journal. Middle East Institute. 36 (3): 319–335. JSTOR 4326424.

- Oliver, Roland Anthony; Atmore, Anthony (2001-08-16). Medieval Africa, 1250-1800. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-79372-8. Retrieved 2013-03-27.

- Petersen, Andrew (2002-03-11). Dictionary of Islamic Architecture. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-203-20387-3. Retrieved 2013-03-24.

- Smith, Sir William (1872). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. John Murray. p. 338. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- Walz, Terence (1975). "Egypt in Africa: A Lost Perspective in Artisans et Commercants au Caire au XVIIIe Siecle by Andre Raymond". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. Boston University African Studies Center. 8 (4): 652–665. doi:10.2307/216700. JSTOR 216700.

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Augilæ". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Augilæ". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.