Subpixel rendering

Subpixel rendering is used to increase the apparent resolution of a computer's display. It takes advantage of the fact that each pixel on a color liquid-crystal display (LCD) or similar is composed of individual red, green, and blue components — subpixels — with different locations, so that the color also causes the image to shift in space.

A single pixel on a color display is made of several subpixels, typically three arranged left-to-right as red, green, blue (RGB). The components are easily visible when viewed with a small magnifying glass, such as a loupe. These pixel components appear as a single color to the human eye because of blurring by the optics and spatial integration by nerve cells in the eye. However the eye is much more sensitive to the location. Therefore, turning on the GB of one pixel and the R of the next one to the right will produce a white dot but it will appear to be 1/3 of a pixel to the right of the white dot that you would see from the RGB of the first pixel.

Subpixel rendering takes advantage of this to provide three times the horizontal resolution of the rendered image, though it has to blur this image to produce the correct color by making sure the same amount of red, green, and blue are turned on as when no subpixel rendering is being done.

![]()

![]()

Subpixel rendering requires the software to know the layout of the subpixels. The most common reason it is wrong is monitors that can be rotated 90 (or 180) degrees, though monitors are manufactured with other arrangements of the subpixels, such as BGR or in triangles, or with 4 colors like RGBW squares. On any such display the result of incorrect subpixel rendering will be worse than if no subpixel rendering was done at all (it will not produce color artifacts, but it will produce noisy edges).

Subpixel rendering is virtually impossible on a CRT. It would require knowing where the electron beam for each pixel hits the display's aperture grille with far greater precision than variations in typical beam steering electronics and magnets.

Subpixel rendering does not help once the resolution of the display becomes so high the user cannot perceive the positioning changes. For this reason, devices with high DPI displays may not use subpixel rendering.

History and patents

The origin of subpixel rendering as used today remains controversial. Apple Inc., IBM, and Microsoft patented various implementations with certain technical differences owing to the different purposes their technologies were intended for.[1]

Microsoft had several patents in the United States on subpixel rendering technology for text rendering on RGB Stripe layouts. The patents 6,219,025, 6,239,783, 6,307,566, 6,225,973, 6,243,070, 6,393,145, 6,421,054, 6,282,327, 6,624,828 were filed between October 7, 1998, and October 7, 1999, and expired on July 30, 2019.[2] Analysis of the patent by FreeType[3] indicates that the idea of subpixel rendering is not covered by the patent, but by the actual filter used as a last step to balance the color. Microsoft's patent describes the smallest filter possible that distributes each subpixel value to an equal amount of R,G, and B pixels. Any other filter will either be blurrier or will introduce color artifacts.

Apple was able to use it in Mac OS X due to a patent cross-licensing agreement.[4]

Apple II

It is sometimes claimed (such as by Steve Gibson[5]) that the Apple II, introduced in 1977, supports an early form of subpixel rendering in its high-resolution (280×192) graphics mode. However, as explained below, the method Gibson describes can also be viewed as a limitation of the way the machine generates color, rather than as a technique intentionally exploited by programmers to increase resolution.

David Turner of the FreeType project criticized Gibson's theory as to the invention, at least as far as patent law is concerned, in the following way: "For the record, the Wozniak patent is explicitly referenced in the [Microsoft U.S. Patent 6,188,385], and the claims are worded precisely to avoid colliding with it (which is easy, since the Apple II only used 2 "sub-pixels", instead of the 'at minimum 3' claimed by MS)."[6] Turner further explains his view:

Under the current US regime, any minor improvement to a previous technique can be considered an "invention" and "protected" by a patent under the right circumstances (e.g. if it's not totally trivial), If [sic] we look at [Microsoft's U.S. Patent 6,219,025], we see that the Apple II Wozniak patent [U.S. Patent 4,136,359] covering this machine's display technique is listed first in the [Microsoft] patents' citations. This shows that both Microsoft and the patent examiner who granted the patents were aware of this "prior art".[2]

The bytes that comprise the Apple II high-resolution screen buffer contain seven visible bits (each corresponding directly to a pixel) and a flag bit used to select between purple/green or blue/orange color sets. Each pixel, since it is represented by a single bit, is either on or off; there are no bits within the pixel itself for specifying color or brightness. Color is instead created as an artifact of the NTSC color encoding scheme, determined by horizontal position: pixels with even horizontal coordinates are always purple (or blue, if the flag bit is set), and odd pixels are always green (or orange). Two lit pixels next to each other are always white, regardless of whether the pair is even/odd or odd/even, and irrespective of the value of the flag bit. The foregoing is only an approximation of the true interplay of the digital and analog behavior of the Apple's video output circuits on one hand, and the properties of real NTSC monitors on the other hand. However, this approximation is what most programmers of the time would have in mind while working with the Apple's high-resolution mode.

Gibson's example claims that because two adjacent bits make a white block, there are in fact two bits per pixel: one which activates the purple left half of the pixel, and the other which activates the green right half of the pixel. If the programmer instead activates the green right half of a pixel and the purple left half of the next pixel, then the result is a white block that is 1/2 pixel to the right, which is indeed an instance of subpixel rendering. However, it is not clear whether any programmers of the Apple II have considered the pairs of bits as pixels—instead calling each bit a pixel. While the quote from Apple II inventor Steve Wozniak on Gibson's page seems to imply that vintage Apple II graphics programmers routinely used subpixel rendering, it is difficult to make a case that many of them thought of what they were doing in such terms.

The flag bit in each byte affects color by shifting pixels half a pixel-width to the right. This half-pixel shift was exploited by some graphics software, such as HRCG (High-Resolution Character Generator), an Apple utility that displayed text using the high-resolution graphics mode, to smooth diagonals. (Many Apple II users had monochrome displays, or turned down the saturation on their color displays when running software that expected a monochrome display, so this technique was useful.) Although it did not provide a way to address subpixels individually, it did allow positioning of pixels at fractional pixel locations, and can thus be considered a form of subpixel rendering. However, this technique is not related to LCD subpixel rendering as described in this article.

IBM

IBM's U.S. Patent #5341153 — Filed: 1988-06-13, "Method of and apparatus for displaying a multicolor image" may cover some of these techniques.

ClearType

Microsoft announced its subpixel rendering technology, called ClearType, at COMDEX in 1998.[7] Microsoft published a paper in May 2000, Displaced Filtering for Patterned Displays, describing the filtering behind ClearType.[8] It was then made available in Windows XP, but it was not activated by default until Windows Vista. (Windows XP OEMs, however, could and did change the default setting.)[9]

FreeType

FreeType, the library used by most current software on the X Window System, contains two open source implementations. The original implementation uses the ClearType antialiasing filters and carries the following notice: "The colour filtering algorithm of Microsoft's ClearType technology for subpixel rendering is covered by patents; for this reason the corresponding code in FreeType is disabled by default. Note that subpixel rendering per se is prior art; using a different colour filter thus easily circumvents Microsoft's patent claims."[3][2]

FreeType offers a variety of color filters. Since version 2.6.2, the default filter is light, a filter that is both normalized (value sums up to 1) and color-balanced (eliminate color fringes at the cost of resolution).[10]

Since version 2.8.1, a second implementation exists, called Harmony, that "offers high quality LCD-optimized output without resorting to ClearType techniques of resolution tripling and filtering". This is the method enabled by default. When using this method, "each color channel is generated separately after shifting the glyph outline, capitalizing on the fact that the color grids on LCD panels are shifted by a third of a pixel. This output is indistinguishable from ClearType with a light 3-tap filter."[11] Since the Harmony method does not require additional filtering, it is not covered by the ClearType patents.

SubLCD

SubLCD is another open-source subpixel rendering method that claims to not infringe existing patents, and promises to remain unpatented.[12] It uses a "2-pixel" subpixel rendering,[13] where G is one subpixel, and the R and B of two adjacent pixels are combined into a "purple subpixel", to avoid the Microsoft patent. This also has the claimed advantage of a more equal perceived brightness of the two subpixels, somewhat easier power-of-2 math, and a sharper filter. However it only produces two-thirds of the resulting resolution.

David Turner was however skeptical of SubLCD's author's claims: "Unfortunately, I, as the FreeType author, do not share his enthusiasm. The reason is precisely the very vague patent claims [by Microsoft] described previously. To me, there is a non-negligible (even if small) chance, that these claims also cover the SubLCD technique. The situation would probably be different if we could invalidate the broader patent claims, but this is not the case currently."[2]

CoolType

Adobe created their own subpixel renderer called CoolType, allowing them to display documents the same way across various operating systems: Windows, MacOS, Linux etc. When it was launched around the year 2001, CoolType supported a wider range of fonts than Microsoft's ClearType, which at the time was limited to TrueType fonts, whereas Adobe's CoolType also supported PostScript fonts (and their OpenType equivalent as well).[14]

OS X

Mac OS X used to use subpixel rendering as well, as part of Quartz 2D. However, it was removed after the introduction of Retina displays. Unlike Microsoft's implementation, which favors a tight fit to the grid (font hinting) to maximize legibility, Apple's implementation prioritizes the shape of the glyphs as set out by their designer.[15]

PenTile

Starting in 1992, Candice H. Brown Elliott researched subpixel rendering and novel layouts, the PenTile matrix family pixel layout, which worked together with sub pixel rendering algorithms to raise the resolution of color flat-panel displays.[16] In 2000, she co-founded Clairvoyante, Inc. to commercialize these layouts and subpixel rendering algorithms. In 2008, Samsung purchased Clairvoyante and simultaneously funded a new company, Nouvoyance, Inc., retaining much of the technical staff, with Ms. Brown Elliott as CEO.[17]

With subpixel rendering technology, the number of points that may be independently addressed to reconstruct the image is increased. When the green subpixels are reconstructing the shoulders, the red subpixels are reconstructing near the peaks and vice versa. For text fonts, increasing the addressability allows the font designer to use spatial frequencies and phases that would have created noticeable distortions had it been whole pixel rendered. The improvement is most noted on italic fonts which exhibit different phases on each row. This reduction in moiré distortion is the primary benefit of subpixel rendered fonts on the conventional RGB Stripe panel.

Although subpixel rendering increases the number of reconstruction points on the display this does not always mean that higher resolution, higher spatial frequencies, more lines and spaces, may be displayed on a given arrangement of color subpixels. A phenomenon occurs as the spatial frequency is increased past the whole pixel Nyquist limit from the Nyquist–Shannon sampling theorem: chromatic aliasing (color fringes) may appear with higher spatial frequencies in a given orientation on the color subpixel arrangement.

Example with the common RGB stripes layout

For example, consider an RGB Stripe Panel:

RGBRGBRGBRGBRGBRGB WWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWW R = red RGBRGBRGBRGBRGBRGB is WWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWW G = green RGBRGBRGBRGBRGBRGB perceived WWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWW where B = blue RGBRGBRGBRGBRGBRGB as WWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWW W = white RGBRGBRGBRGBRGBRGB WWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWW

Shown below is an example of black and white lines at the Nyquist limit, but at a slanting angle, taking advantage of subpixel rendering to use a different phase each row:

RGB___RGB___RGB___ WWW___WWW___WWW___ R = red _GBR___GBR___GBR__ is _WWW___WWW___WWW__ G = green __BRG___BRG___BRG_ perceived __WWW___WWW___WWW_ where B = blue ___RGB___RGB___RGB as ___WWW___WWW___WWW _ = black ____GBR___GBR___GB ____WWW___WWW___WW W = white

Shown below is an example of chromatic aliasing when the traditional whole pixel Nyquist limit is exceeded:

RG__GB__BR__RG__GB YY__CC__MM__YY__CC R = red Y = yellow RG__GB__BR__RG__GB is YY__CC__MM__YY__CC G = green C = cyan RG__GB__BR__RG__GB perceived YY__CC__MM__YY__CC where B = blue M = magenta RG__GB__BR__RG__GB as YY__CC__MM__YY__CC _ = black RG__GB__BR__RG__GB YY__CC__MM__YY__CC

This case shows the result of attempting to place vertical black and white lines at four subpixels per cycle on the RGB Stripe architecture. One can visually see that the lines, instead of being white, are colored. Starting from the left, the first line is red combined with green to produce a yellow-colored line. The second line is green combined with blue to produce a pastel cyan-colored line. The third line is blue combined with red to produce a magenta-colored line. The colors then repeat: yellow, cyan, and magenta. This demonstrates that a spatial frequency of one cycle per four subpixels is too high. Attempts to go to a yet higher spatial frequency, such as one cycle per three subpixels, would result in a single solid color.

Some LCDs compensate the inter-pixel color mix effect by having borders between pixels slightly larger than borders between subpixels. Then, in the example above, a viewer of such an LCD would see a blue line appearing adjacent to a red line instead of a single magenta line.

Example with RBG-GBR alternated stripes layout

Novel subpixel layouts have been developed to allow higher real resolution without chromatic aliasing. Shown here is one of the member of the PenTile matrix family of layouts. Shown below is an example of how a simple change to the arrangement of color subpixels may allow a higher limit in the horizontal direction:

RBGRBGRBGRBGRBGRBG GBRGBRGBRGBRGBRGBR RBGRBGRBGRBGRBGRBG GBRGBRGBRGBRGBRGBR RBGRBGRBGRBGRBGRBG GBRGBRGBRGBRGBRGBR

In this case, the red and green order are interchanged every row to create a red and green checkerboard pattern with blue stripes. Note that the vertical subpixels could be split in half vertically to double the vertical resolution as well. The current LCD panels already typically use two color LEDs (aligned vertically and displaying the same lightness, see the zoomed images below) to illuminate each vertical subpixel. This layout is one of the PenTile matrix family of layouts. When displaying the same number of black-white lines, the blue subpixels are set at half brightness "b":

Rb_Rb_Rb_Rb_Rb_Rb_ Gb_Gb_Gb_Gb_Gb_Gb_ Rb_Rb_Rb_Rb_Rb_Rb_ Gb_Gb_Gb_Gb_Gb_Gb_ Rb_Rb_Rb_Rb_Rb_Rb_ Gb_Gb_Gb_Gb_Gb_Gb_

Notice that every column that turns on comprises red and green subpixels at full brightness and blue subpixels at half value to balance it to white. Now, one may display black and white lines at up to one cycle per three subpixels without chromatic aliasing, twice that of the RGB Stripe architecture.

Non-striped variants of the RBG-GBR alternated layout

Variants of the previous layout have been proposed by Clairvoyante/Nouvoyance (and demonstrated by Samsung) as members of the PenTile matrix family of layouts specifically designed for subpixel rendering efficiency.

For example, taking advantage of the doubled visible horizontal resolution, one could double the vertical resolution to make the definition more isotropic. However this would reduce the aperture of pixels, producing lower contrasts. A better alternative uses the fact that the blue subpixels are those that contribute the least to the visible intensity, so that they are less precisely located by the eye. Blue subpixels are then rendered just as a diamond in the center of a pixel square, and the rest of the pixel surface is split in four parts as a checker board of red and green subpixels with smaller sizes. Rendering images with this variant can use the same technique as before, except that now there's a near-isotropic geometry that supports both the horizontal and the vertical with the same geometric properties, making the layout ideal for displaying the same image details when the LCD panel can be rotated.

The doubled vertical and horizontal visual resolution enables reduction of the subpixel density of about 33%, in order to increase their aperture (also of about 33%), with the same separation distance between subpixels (for their electronic interconnection). It also enables reduction of the power dissipation of about 50%, with a white/black contrast increased of about 50%, and still a visual-pixel resolution enhanced by about 33% (i.e. about 125 dpi instead of 96 dpi), but with only half the total number of subpixels for the same displayed surface.

Checkered RG-BW layout

Another variant, called the RGBW Quad, uses a checkerboard with 4 subpixels per pixel. This adds a white subpixel, or more specifically, replaces one of the green subpixels of Bayer filter Pattern with a white subpixel to increase contrast and reduce the energy needed to illuminate white pixels. This is because color filters in classic RGB striped panels absorb more than 65% of the total white light used to illuminate the panel. As each subpixel is a square instead of a thin rectangle, this also increases the aperture with the same average subpixel density and same pixel density along both axes. As the horizontal density is reduced and the vertical density remains identical (for the same square pixel density), it becomes possible to increase the pixel density of about 33% while maintaining the contrast comparable to classic RGB or BGR panels, due to the more efficient light usage and lowered absorption levels by the color filters.

It is not possible to use subpixel rendering to increase resolution without creating color fringes similar to those seen in classic RGB or BGR striped panels. However, the increased resolution compensates for this, and their effective visible color is also reduced by the presence of 'color-neutral' white subpixels.

However, this layout allows a better rendering of greys, at the price of a lower color separation. This is consistent with human vision and with modern image and video compression formats (like JPEG and MPEG) used in modern HDTV transmissions and in Blu-ray Discs.

Yet another variant, a member for the PenTile matrix family of subpixel layouts, alternates between subpixel order RGBW / BWRG every other row. This allows subpixel rendering to increase resolution without chromatic aliasing. As before, the increased transmittance using the white subpixel allows higher subpixel density, but in this case, the displayed resolution is even higher due to the benefits of subpixel rendering:

RGBWRGBWRGBW BWRGBWRGBWRG RGBWRGBWRGBW BWRGBWRGBWRG RGB_RGB_RGB_ _W___W___W__ RGB_RGB_RGB_ _W___W___W__

Visual resolution versus pixel resolution and software compatibility

Thus, not all layouts are created equal. Each particular layout may have a different 'visual resolution': modulation transfer function limit (MTFL), defined as the highest number of black and white lines that may be simultaneously rendered without visible chromatic aliasing.

However, such alternate layouts are still not compatible with subpixel rendering font algorithms used in Windows, Mac OS X and Linux. These currently support only the RGB or BGR horizontal striped subpixel layouts (rotated monitor subpixel rendering is not supported on Windows or Mac OS X, but is supported on Linux for most desktop environments). However, the PenTile matrix displays have a built-in subpixel rendering engine that allows conventional RGB data sets to be converted to the layouts, providing plug-and-play compatibility with conventional layout displays. New display models should be proposed in the future that allow monitor drivers to specify their visual resolution separately from the full pixel resolution and the relative position offsets of visible subpixels for each color plane, as well as their respective contribution to white intensity. Such monitor drivers would allow renderers to correctly adjust their geometry transform matrices to correctly compute the values of each color plane, and take advantage of subpixel rendering with the lowest chromatic aliasing.

Examples

The photos below were taken with a Canon PowerShot A470 digital camera using 'Super Macro' mode and 4.0× digital zoom. The screen used was that integrated into a Lenovo G550 laptop. Note that the display has RGB pixels. Displays exist in all four patterns, horizontal RGB/BGR and vertical RGB/BGR, but horizontal RGB is the most common.

In addition, several color subpixel patterns have been developed specifically to take advantage of subpixel rendering. The best known of these is the PenTile matrix family of patterns.

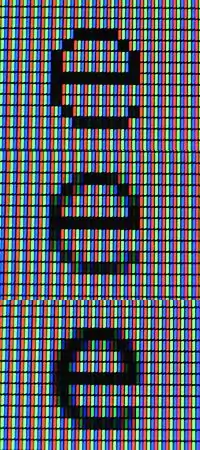

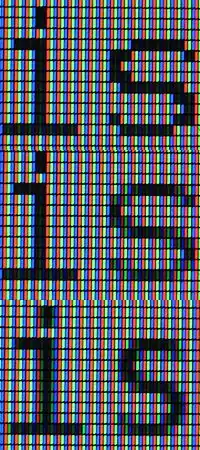

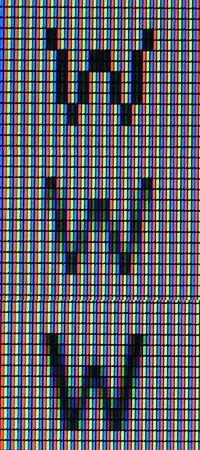

The composite photographs below show three methods of fonts rendering for comparison. From top: Monochrome; Traditional (whole pixel) spatial anti-aliasing; Subpixel rendering.

- Composite macro photograph of three types of rendering: monochrome, traditional antialiasing, subpixel rendering (from top to bottom)

Lower case e

Lower case e Lower case is

Lower case is Lower case w

Lower case w

- Subpixel rendered with FreeType

Lower case e

Lower case e Lower case is

Lower case is Lower case w

Lower case w

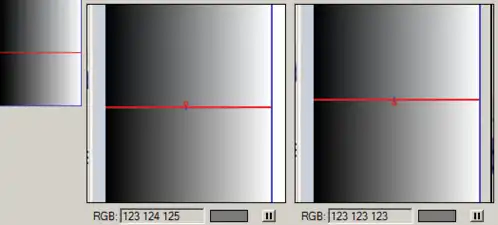

A subpixel accurate gradient.

A subpixel accurate gradient.

References

- John Markoff, "Microsoft's Cleartype Sets Off Debate on Originality Archived 2017-04-21 at the Wayback Machine", New York Times, December 7, 1998

- David Turner (June 1, 2007). "ClearType Patents, FreeType and the Unix Desktop: an explanation". Archived from the original on 2009-03-31. Retrieved April 9, 2009.

- "FreeType and Patents". FreeType.org. February 13, 2018. Archived from the original on 2018-11-10. Retrieved November 29, 2018.

- "LCD Rendering Patches". September 24, 2006. Archived from the original on 2011-06-03. Retrieved April 9, 2009.

- "GRC - The Origins of Sub-Pixel Font Rendering". grc.com. Archived from the original on 2006-03-06. Retrieved 2006-03-02.

- David Turner (24 Sep 20:00 2006) LCD Rendering Patches Archived 2007-02-08 at the Wayback Machine (was Re: [ft] Regression in rendering quality with subpixel antialiasing)

- ICT Bill Gates 1998 keynote comdex 1998, archived from the original on 2021-11-30, retrieved 2021-11-30

- Platt, John; Keely, Bert; Hill, Bill; Dresevic, Bodin; Betrisey, Claude; Mitchell, Don P.; Hitchcock, Greg; Blinn, Jim; Whitted, Turner (2000-05-01). "Displaced Filtering for Patterned Displays": 296–299. Archived from the original on 2021-11-30. Retrieved 2021-11-30.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Greg Hitchcock (with introduction by Steven Sinofsky) "Engineering Changes to ClearType in Windows 7 Archived 2012-12-18 at the Wayback Machine", MSDN blogs, June 23, 2009

- "On slight hinting, proper text rendering, stem darkening and LCD filters". freetype.org. Archived from the original on 2020-11-12. Retrieved 2020-11-14.

- Lemberg, Werner (2017-09-16). "Announcing FreeType 2.8.1". Archived from the original on 2019-11-16. Retrieved 2019-04-30.

- "SubLCD". www.oyhus.no. Archived from the original on 2006-11-09. Retrieved 2006-08-30.

- "SubLCD". Archived from the original on 2006-11-09. Retrieved 2006-08-30.

- Felici, James (April 2000) "ClearType, CoolType: The Eyes Have It", Seybold Report on Internet Publishing, Vol. 4 Issue 8

- "The Ails Of Typographic Anti-Aliasing". November 2, 2009. Archived from the original on 2014-08-09. Retrieved 2014-08-11.

- Brown Elliott, C.H., "Reducing Pixel Count without Reducing Image Quality" Archived 2012-03-02 at the Wayback Machine, Information Display Magazine, December 1999, ISSN 0362-0972

- Nouvoyance. "Press Release: Samsung Electronics Acquires Clairvoyante's IP Assets". Archived from the original on February 27, 2012. Retrieved August 19, 2010.

External links

- Former IBM researcher Ron Feigenblatt's remarks on Microsoft ClearType

- Pixel Borrowing, ClearType and Antialiasing at the Wayback Machine (archived October 12, 2007)

- John Daggett's Subpixel Explorer Archived 2016-01-31 at the Wayback Machine—requires Firefox to display properly

- Texts Rasterization Exposures Article from the Anti-Grain Geometry Project.

- Engelhardt, Thomas (2013). "Low-Cost Subpixel Rendering for Diverse Displays". Computer Graphics Forum. 33 (1): 199–209. doi:10.1111/cgf.12267. S2CID 9851327. http://jankautz.com/publications/SubpixelCGF13.pdf

- http://www.cahk.hk/innovationforum/subpixel_rendering.pdf