Boiling liquid expanding vapor explosion

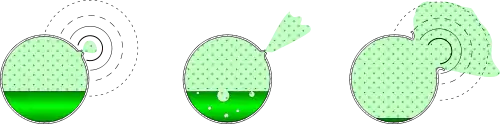

A boiling liquid expanding vapor explosion (BLEVE, /ˈblɛviː/ BLEV-ee) is an explosion caused by the rupture of a vessel containing a pressurized liquid that has reached a temperature above its boiling point.[1][2] Because the boiling point of a liquid rises with pressure, the contents of the pressurized vessel can remain a liquid as long as the vessel is intact. If the vessel's integrity is compromised, the loss of pressure drops the boiling point, which can cause the liquid to convert to a gas expanding rapidly. If the gas is combustible, as in the case with hydrocarbons and alcohols, further damage can be caused by the ensuing fire.

Mechanism

There are three key elements that cause a BLEVE.[3]

- A substance in liquid form at a temperature above its normal atmospheric pressure boiling point.

- A containment vessel maintains the pressure that keeps the substance in liquid form.

- A sudden loss of containment that rapidly drops the pressure.

Typically, a BLEVE starts with a container of liquid which is held above its normal, atmospheric pressure boiling temperature. Many substances normally stored as liquids, such as CO2, propane, and other similar industrial gases have boiling temperatures far below room temperature when at atmospheric pressure. In the case of water, a BLEVE could occur if a pressurized chamber of water is heated far beyond the standard 100 °C (212 °F). That container, because the boiling water pressurizes it, must be capable of holding liquid water at very high temperatures.

If the pressurized vessel, containing liquid at high temperature (which may be room temperature, depending on the substance) ruptures, the pressure which prevents the liquid from boiling is lost. If the rupture is catastrophic, where the vessel is immediately no longer capable of holding any pressure, then there suddenly exists a large mass of liquid which is at a very high temperature and very low pressure. This causes a portion of the liquid to "instantaneously" boil, which in turn causes an extremely rapid expansion. Depending on temperatures, pressures and the substance involved, that expansion may be so rapid that it can be classified as an explosion, fully capable of inflicting severe damage on its surroundings.

Water example

For example, a tank of pressurized liquid water held at 204.4 °C (400 °F) might be pressurized to 1.7 MPa (250 psi) above atmospheric ("gauge") pressure. If the tank containing the water were to rupture, there would for a brief moment exist a volume of liquid water which would be at:

- Atmospheric pressure

- Temperature of 204.4 °C (400 °F).

At atmospheric pressure the boiling point of water is 100 °C (212 °F) - liquid water at atmospheric pressure does not exist at temperatures higher than 100 °C (212 °F). At that moment, the water would boil and turn to vapour explosively, and the 204.4 °C (400 °F) liquid water turned to gas would take up significantly more volume (≈1,600-fold) than it did as liquid, causing a vapour explosion. Such explosions can happen when the superheated water of a boiler escapes through a crack in a boiler, causing a boiler explosion.

BLEVEs without chemical reactions

A BLEVE does not have to be a chemical explosion, nor does there need to be a fire: however, if a flammable substance is subject to a BLEVE, it may also be subject to intense heating, either from an external source of heat which may have caused the vessel to rupture in the first place, or from an internal source of localized heating such as skin friction. This heating can cause a flammable substance to ignite, adding a secondary explosion caused by the primary BLEVE. While the blast effects of any BLEVE can be devastating, a flammable substance such as propane can add significantly to the danger.

While the term BLEVE is most often used to describe the results of a container of flammable liquid rupturing due to fire, a BLEVE can occur even with a non-flammable substance such as water,[4] liquid nitrogen,[5] liquid helium or other refrigerants or cryogenics, and therefore is not usually considered a type of chemical explosion. Note that in the case of liquefied gasses, BLEVEs can also be hazardous because of rapid cooling due to the absorption of the enthalpy of vapourization (e.g. frostbites), or because of possible asphyxiation if a large volume of gas is produced and not rapidly dispersed (e.g. inside a building, or in a trough in the case of heavier-than-air gasses), or because of the toxicity of the gasses produced.

Fires

BLEVEs can be caused by an external fire near the storage vessel causing heating of the contents and pressure build-up. While tanks are often designed to withstand great pressure, constant heating can cause the metal to weaken and eventually fail. If the tank is being heated in an area where there is no liquid, it may rupture faster without the liquid absorbing the heat. Gas containers are usually equipped with relief valves that vent off excess pressure, but the tank can still fail if the pressure is not released quickly enough.[1] Relief valves are sized to release pressure fast enough to prevent the pressure from increasing beyond the strength of the vessel, but not so fast as to be the cause of an explosion. An appropriately sized relief valve will allow the liquid inside to boil slowly, maintaining a constant pressure in the vessel until all the liquid has boiled and the vessel empties.[6]

If the substance involved is flammable, it is likely that the resulting cloud of the substance will ignite after the BLEVE has occurred, forming a fireball and possibly a fuel-air explosion. If the materials are toxic, a large area will be contaminated.[7]

Incidents

The term "BLEVE" was coined by three researchers at the Factory Mutual insurance company, in the analysis of an accident at one of their research facilities in 1957 involving a chemical reactor vessel.[8]

On 18 August 1959, the Kansas City Fire Department suffered its second largest loss of life in the line of duty, when a 25,000 gallon (95,000 liters) gasoline tank exploded during a fire on Southwest Boulevard, killing 5 firefighters.[9][10]

Examples of other BLEVE incidents have included:

- 28 June 1959: Meldrim Trestle Disaster in Meldrim, Georgia US.

- 28 March 1960: Cheapside Street whisky bond fire in Glasgow, Scotland.[11]

- 4 January 1966: Feyzin disaster; The explosion of an LPG storage tank near Feyzin, France.

- 21 June 1970: The explosion of a derailed propane tank car in Crescent City, Illinois.[12]

- 5 July 1973: Kingman explosion; An explosion of a burning propane tank car in Kingman, Arizona.[13]

- 12 February 1974: Oneonta Explosion; A 122-car Delaware and Hudson freight train derails four miles (6.4 km) north of Oneonta, New York. 54 people were injured when a propane car that had been punctured when the train derailed and two other propane tanker cars exploded due to BLEVE. One tank was found on the other side of the Susquehanna River.[14]

- 31 January 1978: rupture of a liquid nitrogen tank[15] at an Air Products & Chemicals and Mobay Chemical Corporation facility in New Martinsville, West Virginia[16]

- 23 February 1978: Waverly, Tennessee, tank car explosion; a tank car carrying liquefied petroleum gas exploded as a result of a cleanup related to a train derailment.

- 1 July 1978: The Los Alfaques disaster; an overloaded tanker truck carrying liquefied propylene exploded next to a camping site in Alcanar, Spain, resulting in 217 deaths.

- 19 November 1984: A fire at a liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) tank farm triggers multiple BLEVEs in the San Juanico disaster at San Juan Ixhuatepec, near Mexico City.[17]

- 23 December 1988: Memphis tanker truck disaster; a tank truck carrying propane ruptured, causing ignition of leaking gas; the tank was subsequently launched from the crash site and crashed into a nearby building.

- 1 April 1990: Sydney, Australia; A near-disaster occurred when Boral's St. Peters facility experienced an LPG fuel tank explosion on the night of 1 April 1990. A fire broke out at about 9:00 p.m., burning for over nine hours. A 100-tonne LPG cylinder and many smaller tanks exploded. The 100-tonne tank was shot from its support structure and bounced along the ground, coming to rest in the Alexandria Canal next to the site. Evacuations involved around 3,000 people from the surrounding area, in a two km radius. There were no casualties.[18]

- 9 April 1998: Albert City, Iowa; Herrig Brothers Farm Propane Tank Explosion: an 18,000-gallon propane tank exploded at the Herrig Brothers farm in Albert City, Iowa. The explosion killed two volunteer firefighters and injured seven other emergency response personnel. Several buildings were also damaged by the blast.[19][20]

- 1 May 1999: Explosion of a propane tank truck near Kamena Vourla, Greece, resulting in 5 deaths.

- 10 August 2008: Toronto propane explosion; multiple explosions at a propane facility in Toronto, Ontario.[21]

- 3 April 2017: Semi-Closed Receiver, Condensate, BLEVE, Loy Lange Box Co, St Louis, Missouri.[22][23]

- 6 August 2018: Tanker truck explosion near an airport in Bologna, Italy.[24][25]

- 24 December 2022: Tanker truck explosion near a hospital in Boksburg, South Africa.[26]

- 26 August 2023: Storage tank explosion in the village of Crevedia, Romania[27]

Safety measures

Some fire mitigation measures are listed under liquefied petroleum gas.

- Maintenance of pressure tanks to avoid damage or corrosion[28]

- Emergency depressurization[3]

- Pressure relief valves[29]

- Passive fire protection[29][28]

- Water spray cooling[29][28]

Transport Canada published a training video for emergency response personnel to respond to and prevent BLEVEs.[28] They also advise that expert advice can be obtained from Transport Canada's Canadian Transport Emergency Centre, CANUTEC.[30]

See also

References

- Kletz, Trevor (March 1970). Critical Aspects of Safety and Loss Prevention. London: Butterworth–Heinemann. pp. 43–45. ISBN 0-408-04429-2.

- "What firefighters need to know about BLEVEs". FireRescue1. 23 July 2020. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020.

- CCPS (2010). Guidelines for Vapor Cloud Explosion, Pressure Vessel Burst, BLEVE, and Flash Fire Hazards (2nd ed.). New York, N.Y. and Hoboken, N.J.: American Institute of Chemical Engineers and John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-25147-8.

- "Temperature Pressure Relief Valves on Water Heaters: test, inspect, replace, repair guide". Inspect-ny.com. Archived from the original on 1 August 2012. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- Haywood, Bryan. "Liquid Nitrogen BLEVE Demo Vid #1". www.safteng.net.

- S., W. (2008). Pressure Relief Valves. Pressure Relief Valve (PRV). Retrieved 2023-08-03.

- "Chemical Process Safety" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- David F. Peterson, BLEVE: Facts, Risk Factors, and Fallacies Archived 3 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Fire Engineering magazine (2002).

- "The Southwest Boulevard Fire: Kansas City Remembers a Tragedy". FIREHOUSE. 30 November 2009.

- "The Southwest Boulevard Fire". YouTube. 14 August 2009. Archived from the original on 23 November 2020.

- Fire Brigades Union. (n.d.). Cheapside street fire, Glasgow: 28th March 1960. Fire Brigades Union. Retrieved 2023-03-08.

- Bonty, J. (2020, June 20). The day crescent city became a fireball. The Daily Journal. Retrieved 2023-03-08.

- Memorial Monday - Kingman Explosion (AZ) - NFFF. National Fallen Firefighters Foundation. (2021, July 24). Retrieved 2023-03-08.

- "54 HURT IN BLAST OF FREIGHT CARS". New York Times. Oneonta, NY. 12 February 1974. Retrieved 19 February 2023.

- "State ex rel. Vapor Corp. v. Natick". Supreme Court of Appeals of West Virginia. 12 July 1984. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- "New Martinsville, WV Liquid Oxygen Explosion, Feb 1978 | GenDisasters ... Genealogy in Tragedy, Disasters, Fires, Floods". Archived from the original on 28 January 2022. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- "Pemex LPG Terminal, Mexico City, Mexico". 19 November 1984. Retrieved 8 March 2023.

- "Getting Into the European Market". boral.com History. Boral. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- "INVESTIGATION REPORT - Propane Tank Explosion". U.S. Chemical Safety Board. 23 June 1999.

- "Herrig Brothers Farm Propane Tank Explosion". U.S. Chemical Safety Board. 23 June 1999.

- Lawlor, M. (2018, August 10). 10-year anniversary of the Sunrise Propane explosion. CityNews. Retrieved 2023-03-08.

- "Loy Lange Box Company Pressure Vessel Explosion". U.S. Chemical Safety Board. 29 July 2022.

- "Pressure Vessel Explosion at Loy-Lange Box Company". U.S. Chemical Safety Board. 29 July 2022.

- "Bologna tanker truck explosion leaves two dead". BBC News. 6 August 2018. Retrieved 6 August 2018.

- "Tanker explodes on the road near Bologna airport". The Local Italy. 6 August 2018. Retrieved 8 August 2018.

- "Boksburg tanker explosion: Police arrest driver for culpable homicide after 15 confirmed dead". news24.

- "At least one dead, 46 hurt after explosions in Romania". Raidió Teilifís Éireann via Reuters.

- "BLEVE – Response and Prevention". tc.canada.ca. Transport Canada. 26 November 2018. Archived from the original on 17 July 2020. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- "BLEVE Safety Precautions" (PDF). noaa.gov. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 April 2019. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- "CANUTEC".

External links

- BLEVE Demo on YouTube – video of a controlled BLEVE demo

- huge explosions on YouTube – video of propane and isobutane BLEVEs from a train derailment at Murdock, Illinois (3 September 1983)

- Propane BLEVE on YouTube – video of BLEVE from the Toronto propane depot fire

- Moscow Ring Road Accident on YouTube – Dozens of LPG tanks BLEVEs after a road accident in Moscow

- Kingman, AZ BLEVE – An account of 5 July 1973 explosion in Kingman, with photographs

- Propane Tank Explosions – Description of circumstances required to cause a propane tank BLEVE.

- Analysis of BLEVE Events at DOE Sites – Details physics and mathematics of BLEVEs.

- HID – Safety Report Assessment Guide: Whisky Maturation Warehouses – The liquor is aged in wooden barrels that can suffer BLEVE.

.jpg.webp)