Bacterial cellular morphologies

Bacterial cellular morphologies are morphologies that are characteristic of various types bacteria and often a key factor in identifying bacteria species. Their direct examination under the light microscope enables the classification of these bacteria and archaea.

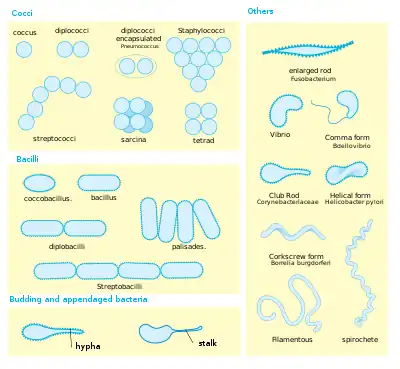

Generally, the basic morphologies are spheres (coccus) and round-ended cylinders or rod shaped (bacillus). But, there are also other morphologies such as helically twisted cylinders (example Spirochetes), cylinders curved in one plane (selenomonads) and unusual morphologies (the square, flat box-shaped cells of the Archaean genus Haloquadratum). Other arrangements include pairs, tetrads, clusters, chains and palisades.

Coccus

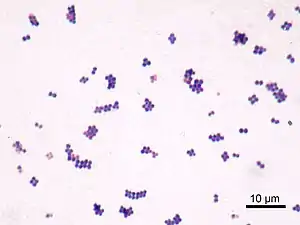

A coccus (plural cocci, from the Latin coccinus (scarlet) and derived from the Greek kokkos (berry)) is any microorganism (usually bacteria)[1] whose overall shape is spherical or nearly spherical.[2] Describing a bacterium as a coccus, or sphere, distinguishes it from bacillus, or rod. This is the first of many taxonomic traits for identifying and classifying a bacterium according to binomial nomenclature.

Important human diseases caused by coccoid bacteria include staphylococcal infections, some types of food poisoning, some urinary tract infections, toxic shock syndrome, gonorrhea, as well as some forms of meningitis, throat infections, pneumonias, and sinusitis.[3]

Arrangements

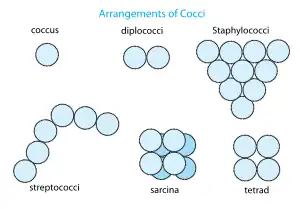

Coccoid bacteria often occur in characteristic arrangements and these forms have specific names as well;[4] listed here are the basic forms as well as representative bacterial genera:

- pairs or diplococci (e.g. Neisseria spp.)

- groups of four or eight known respectively as tetrads and sarcina (e.g. Micrococcus spp.)

- bead-like chains (e.g. Streptococcus spp.)

- grapelike clusters (e.g. Staphylococcus spp.)

Bacillus

A bacillus (plural bacilli) is a rod-shaped bacterium. Although Bacillus, capitalized and italicized, specifically refers to the genus, the word bacillus (plural bacilli) may also be used to describe any rod-shaped bacterium, and in this sense, bacilli are found in many different taxonomic groups of bacteria.

There is no connection between the shape of a bacterium and its colors in the Gram staining.

Coccobacillus

A coccobacillus (plural coccobacilli) is a type of rod-shaped bacteria. The word coccobacillus reflects an intermediate shape between coccus (spherical) and bacillus (elongated).[2] Coccobacilli rods are so short and wide that they resemble cocci. Haemophilus influenzae and Chlamydia trachomatis are coccobacilli. Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans is a gram negative coccobacillus which is prevalent in subgingival plaques. Acinetobacter strains may grow on solid media as coccobacilli.

Coxiella burnetti is also a coccobacillus.[6]

Spiral

Spiral bacteria are another major bacterial cell morphology.[2][7] Spiral bacteria can be sub-classified as spirilla, spirochetes, or vibrios based on the number of twists per cell, cell thickness, cell flexibility, and motility.

Bacteria are known to evolve specific traits to survive in their ideal environment.[8] Bacteria-caused illnesses hinge on the bacteria’s physiology and their ability to interact with their environment, including the ability to shapeshift. Researchers discovered a protein that allows the bacterium Vibrio cholerae to morph into a corkscrew shape that likely helps it twist into — and then escape — the protective mucus that lines the inside of the gut.[8]

See also

- Bacterial morphological plasticity

- Ferdinand Cohn – gave first named shapes of bacteria

References

- Cole JR (January 1990). "Diagnostic Procedure in Veterinary Bacteriology and Mycology". In Carter GR, Cole JR (eds.). 17 - Streptococcus and Related Cocci (Fifth ed.). San Diego: Academic Press. pp. 211–220. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-161775-2.50021-9. ISBN 978-0-12-161775-2.

- Zapun A, Vernet T, Pinho MG (March 2008). "The different shapes of cocci". FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 32 (2): 345–360. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6976.2007.00098.x. PMID 18266741.

- Ryan KJ, Ray CG, eds. (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. ISBN 0-8385-8529-9.

- Salton MR, Kim KS (1996). Baron S, et al. (eds.). Structure. In: Baron's Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). Univ of Texas Medical Branch. ISBN 0-9631172-1-1. (via NCBI Bookshelf).

- Harry E, Monahan L, Thompson L (2006). "Bacterial cell division: the mechanism and its precision". International Review of Cytology. 253: 27–94. doi:10.1016/S0074-7696(06)53002-5. ISBN 978-0-12-373597-3. PMID 17098054.

- McCaul TF, Williams JC (September 1981). "Developmental cycle of Coxiella burnetii: structure and morphogenesis of vegetative and sporogenic differentiations". Journal of Bacteriology. 147 (3): 1063–1076. doi:10.1128/jb.147.3.1063-1076.1981. PMC 216147. PMID 7275931.

- Young KD (September 2006). "The selective value of bacterial shape". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 70 (3): 660–703. doi:10.1128/MMBR.00001-06. PMC 1594593. PMID 16959965.

- Tan YS, Zhang RK, Liu ZH, Li BZ, Yuan YJ (2022). "Microbial Adaptation to Enhance Stress Tolerance". Frontiers in Microbiology. 13: 888746. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2022.888746. PMC 9093737. PMID 35572687.