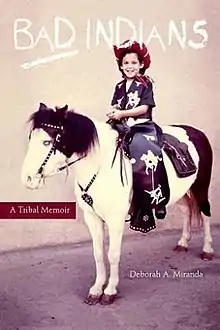

Bad Indians

Bad Indians: A Tribal Memoir is a mixed-genre book by Deborah Miranda published by Heyday Books in 2013. The book is part tribal history of the California Mission Indians and part family memoir.[1] It combines different media and genres including oral histories, newspaper clippings, anthropological recordings, poems, and personal reflection to narrate the stories of Miranda’s family, who were members of the Ohlone/Costanoan – Esselen Nation (a non-profit organization that self-identifies as a Native American tribe), along with the experiences of California Indigenous people from the time of the Spanish missions into the present.[2]

First edition | |

| Author | Deborah A. Miranda |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Autobiography & Memoir |

| Publisher | Heyday Books |

Publication date | January 1, 2013 |

| Media type | Paperback & Ebook |

| Pages | 240 (paperback) |

| ISBN | 9781597142014 |

Plot

The memoir’s structure is a Native epistemology that tells a narrative with emphasis on relationships and a circulatory format.[3] Following a loosely chronological order, the book begins in 1770 with the Spanish building a string of missions along the California coast.[1] Through mimicking the “Mission project” as deployed in the California school curriculum and editing excerpts from a coloring book, Miranda recontextualizes how California Missions and American history are taught in schools.[1] She also pulls from her mother’s extensive genealogy records and her grandfather’s cassette tapes in order to tell the stories of her own family.[1]

Background

During her 10-month sabbatical from Washington and Lee University and after the rediscovery of her grandfather Tom Miranda’s tapes, Miranda began writing her tribal memoir in 2007-2008 while she was back in her home state of California.[4] During this time, Miranda began to research the California Missions and her own family histories, recognizing that these stories were not separate but rather intertwined.[5] As Miranda notes in an interview with Donna Miscolta, “California Indian history is brutal. I learned the realities of it from my father. The academic knowledge came later. And they were the same thing.”[5] In an interview Miranda expresses her inspiration with bringing together the pieces of her story: “Eventually, I remembered Gloria Anzaldua talking about how a mosaic is what you make out of broken pieces, and suddenly, it made sense: I couldn’t ‘reconstruct’ our culture, but I could gather what pieces I could find and try to create something new out of it.”[4]

Major themes

Intervening with the Mission Mythology

According to Lisa Udel, “Miranda works to counter pre-vailing narratives about Native people still evident in contemporary American culture—such as the California school curriculum’s fourth-grade ‘mission project’”[6] Miranda demonstrates how “the Mission Unit” promotes imperialist and racist ideologies, rather than portray an accurate history of California Missions.[7] Miranda combats these overarching mythologies by “writing a tribalography that challenges the official story.”[8] According to Choctaw author LeAnne Howe, who developed the term, tribalography refers to a rhetorical style that Native people use as an “eloquent act of unification.”[9]

In one passage, Miranda recounts her visit to Mission Doloras. During her visit, she meets a mother and her daughter, who are there for the daughter’s Mission Project. In response to a remark about California Natives existence, Miranda reveals that she is a member of the Ohlone/Costanoa Esselen Nation.[7] Miranda focuses on the daughter, recounting that, “Her face drained, her body went stiff, and she stared at me as if I had risen, an Indigenous skeleton clad in decrepit rags, from beneath the clay bricks of the courtyard.”[7] Regarding this story, Shanae A. Martinez notes that, “Miranda's living presence intervenes in the Mission Mythology, which denies the existence of any living Mission Indians and in effect denies their claims to land...she [] epitomizes the process by which settler-colonial metanarratives are institutionally authorized and internalized.”[8]

The power of storytelling

As several critics note, the memoir demonstrates the power of stories and storytelling as vehicles for Indigenous people’s histories and resistance.[4][5][7] In an interview about the memoir Miranda states, “Story is the great healer—of people, of histories, of imbalance.”[4] Lauren Furlan explains how storytelling as a form of historical retelling when she states that “Miranda makes her ancestor’s storytelling a valid mode of Indigenous history-keeping and history-telling, demonstrating that stories of Indigenous life are history in the same way that official records are history.”[10]

One specific story involves a young Indigenous woman named Vicenta Gutierrez, who was sexually assaulted by Padre Real. In her retelling, Isabel narrates the story tersely, stating that “‘the girl went running to her house, saying the Padre had grabbed her.’”[5] According to Shanae A. Martinez, this story counters the mythology of missions being absent of abuse and sexual assault and tells a story about resistance.[8] As Lisa J. Udel states, “Miranda reads Meadows’s use of Vicenta’s story as a form of community activism against ‘silence and lies.’”[6] It works and reworks the functions and expectations of storytelling, for as Furlan elaborates, “we are engaged in a very Indigenous practice: that of storytelling as education, as thought-experiment, as community action to right a wrong, as resistance to representation as victim.”[10]

Content

Genre and sequencing

Through a variety of media, Bad Indians embodies both a fragmented and non-linear structure.[6] As Udel notes, Miranda is able to create a narrative that is “constructed by what she finds, chooses, and takes possession of: Miranda’s intentional compilation that breaks with the traditional autobiographical form. And not just the “pieces” are connected, but so too are tribal history and Miranda’s story across time and space.”[6] The memoir spans decades, drawing connections between the violence inflicted upon Mission Indians and its effects on Miranda's interpersonal relationships.[11]

Media

According to Furlan, Miranda employs a variety of different media and sources in her memoir to reconstruct and decolonize the historical narrative of indigenous people in California and her own indigenous background.[10] Bad Indians is composed of “part historical archive, part family history, part personal narrative, and part poetry.”[10]

Poems

There are a total of ten poems penned by Miranda within the memoir. The first two poems, “Los Pájaros” and “Fisher of Men,” are “based on writings by Junipero Serra.”[7] Furlan notes that Miranda took creative liberties with Serra’s writings to emphasize specific themes present throughout the memoir, like coercive sexual relations between colonizers and Indigenous women and the dehumanizing treatment of Indigenous people by colonizers.[10] As Furlan notes, the alterations to Serra’s accounts of Indigenous people provide colonial documents with an Indigenous perspective regarding Indigenous history.[10]

Articles and newspapers

Articles and newspapers are referenced and depicted in various formats in the memoir. The poem “Old News” is written from an assortment of newspaper excerpts from the Sacramento Union, the Sacramento Daily, the Sacramento Daily Democratic State Journal, and the San Francisco Bulletin.[10] In two essays that discuss derogatory names against Indigenous people, Miranda incorporates an excerpt from Oscar Penn Fitzgerald’s travel book California Sketches and an image of a California State bond “for the ‘suppression of Indian hostilities.’”[10][7] Another newspaper clipping titled “‘Bad Indian Goes on Rampage at Santa Ynez’” depicts an Indigenous man named Juan Miranda who goes “on a rampage” after drinking some “fire water.”[10] According to Furlan, the subsequent poem, “Novena to Bad Indians,” serves as “guidance on how to read” the newspaper clipping through recognition that Indigenous “acts of rebellion” were meant to offset “settler colonial violence.”[10]

Essays

Much of Miranda’s memoir consists of essays regarding Indigenous history in California, her personal narratives about family and Indigeneity, and transcribed recordings from her grandfather’s cassette tapes.[1]

Short stories

Miranda’s short story “Coyote Takes a Trip” appears in the fourth section of the memoir, “Teheyapami Achiska: Home 1961-present.” “Coyote” is a creator in Esselen mythology.[12][1]

Cartoons

There is one cartoon featured in Bad Indians titled “California Pow Wow,” by L. Frank.[1]

Images

Miranda includes images of herself, her family, documents, Indigenous people, works of art by colonizers, and one of J.P. Harrington in her memoir.[1]

Reception

Since its release the memoir has received favorable reviews from Booklist and Native American author Linda Hogan,[7] among others. Kirkus Reviews called it “A searing indictment of the ravages of the past and a hopeful look at the courage to confront and overcome them.”[11] For her memoir Miranda won a 2014 Independent Publisher Book Award gold medal in the Autobiography/Memoir category.[13] Additionally, Miranda won a 2015 PEN Oakland/Josephine Miles Literary Award[14] and was shortlisted for the 2014 William Saroyan International Prize for Writing.[7]

The memoir has also received reviews from other Indigenous women authors. Linda Hogan states that “...this book is groundbreaking not only as literature but as history” and Leslie Marmon Silko says “Miranda takes us on a journey to locate herself by way of the stories of her ancestors and others who come alive through her writing. It's such a fine book that a few words can't do it justice.”[7] Beverly Slapin also states that “Miranda has created an achingly beautiful mosaic out of the broken shards of her people and herself.”[15]

Further reading

- Soldier, Rose Soza War (2016). "Bad Indians: A Tribal Memoir by Deborah A. Miranda (review)". Wicazo Sa Review. 31 (2): 103–106. doi:10.5749/wicazosareview.31.2.0103. Project MUSE 663860.

- “Native Voice TV - Deborah A Miranda, Author of ‘Bad Indians.’” YouTube, 18 July 2013, https://youtu.be/t-nRgNCEFnI.

- Gopi, Anjitha (October 2019). "California: A Tale or Myriad? – Understanding Tribalography Through Deborah Miranda's Bad Indians 2014". International Journal of Multidisciplinary Educational Research. 8 (10(2)): 1–7.

References

- Tschiggfrie, Sarah. "New Book by W&L's Miranda Gives a Voice to California Indians". Washington and Lee University. Archived from the original on 2016-11-09. Retrieved 2016-11-17.

- Miranda, Deborah (2013). Bad Indians. Heyday. ISBN 978-1597142014.

- Welizarowicz, Grzegorz (28 December 2018). "American Indian epistemology in Deborah A. Miranda's Bad Indians: A Tribal Memoir". Beyond Philology (15/4): 117–155. doi:10.26881/bp.2018.4.07. S2CID 216689866.

- Miranda, Deborah A. (15 January 2013). "Q & A with Deborah Miranda". Bad NDNS. Archived from the original on 2015-10-25.

- Miscolta, Donna. "An interview with Deborah Miranda". Archived from the original on 2016-04-28.

- Udel, Lisa J. (2016). "Bad Indians: A Tribal Memoir by Deborah A. Miranda (review)". The American Indian Quarterly. 40 (1): 76–79. doi:10.5250/amerindiquar.40.1.0076. Project MUSE 605551.

- Miranda, Deborah A. (2013). Bad Indians: A Tribal Memoir. Heyday. ISBN 978-1-59714-201-4.

- Martinez, Shanae Aurora (2018). "Intervening in the Archive: Women-Water Alliances, Narrative Agency, and Reconstructing Indigenous Space in Deborah Miranda's Bad Indians: A Tribal Memoir". Studies in American Indian Literatures. 30 (3–4): 54. doi:10.5250/studamerindilite.30.3-4.0054. S2CID 166273109. ProQuest 2176227168.

- Howe, LeAnne (Fall 1999). "Tribalography: The Power of Native Stories". Journal of Dramatic Theory and Criticism: 117–126.

- Furlan, Laura M. (2021). "The Archives of Deborah Miranda's Bad Indians". Studies in American Indian Literatures. 33 (1): 27–54. doi:10.1353/ail.2021.0003. S2CID 238907796. Project MUSE 801923.

- "BAD INDIANS by Deborah A. Miranda". Kirkus Reviews.

- Heberling, Lydia M. (2021). "Surviving Catastrophe: Traveling with Coyote in Bad Indians: A Tribal Memoir". Studies in American Indian Literatures. 33 (1): 1–26. doi:10.1353/ail.2021.0002. S2CID 238945943. Project MUSE 801922.

- "2014 Independent Publisher Book Awards Results". Independent Publisher - feature. Retrieved 2016-11-17.

- "PEN Oakland Awards | PEN Oakland". penoakland.com. Archived from the original on 2016-11-18. Retrieved 2016-11-17.

- Martin, Gabrielle and Lucinda (2018). "Review of Bad Indians: A Tribal Memoir". Zinn Education Project. Archived from the original on 2020-10-03.