Badminton

Badminton is a racquet sport played using racquets to hit a shuttlecock across a net. Although it may be played with larger teams, the most common forms of the game are "singles" (with one player per side) and "doubles" (with two players per side). Badminton is often played as a casual outdoor activity in a yard or on a beach; formal games are played on a rectangular indoor court. Points are scored by striking the shuttlecock with the racquet and landing it within the other team's half of the court.

Two Chinese pairs compete in the mixed doubles gold medal match of the 2012 Olympics | |

| Highest governing body | Badminton World Federation |

|---|---|

| First played | 19th century in Badminton House |

| Characteristics | |

| Contact | None |

| Team members | Singles or doubles |

| Mixed-sex | Yes |

| Type | Racquet sport, Net sport |

| Equipment | Shuttlecock, racquet |

| Presence | |

| Olympic | 1992–present |

| World Games | 1981 |

Each side may only strike the shuttlecock once before it passes over the net. Play ends once the shuttlecock has struck the floor or ground, or if a fault has been called by the umpire, service judge, or (in their absence) the opposing side.[1]

The shuttlecock is a feathered or (in informal matches) plastic projectile that flies differently from the balls used in many other sports. In particular, the feathers create much higher drag, causing the shuttlecock to decelerate more rapidly. Shuttlecocks also have a high top speed compared to the balls in other racquet sports. The flight of the shuttlecock gives the sport its distinctive nature.

The game developed in British India from the earlier game of battledore and shuttlecock. European play came to be dominated by Denmark but the game has become very popular in Asia, with recent competitions dominated by China. In 1992, badminton debuted as a Summer Olympic sport with four events: men's singles, women's singles, men's doubles, and women's doubles;[2] mixed doubles was added four years later. At high levels of play, the sport demands excellent fitness: players require aerobic stamina, agility, strength, speed, and precision. It is also a technical sport, requiring good motor coordination and the development of sophisticated racquet movements.[3]

History

Games employing shuttlecocks have been played for centuries across Eurasia,[lower-alpha 1] but the modern game of badminton developed in the mid-19th century among the expatriate officers of British India as a variant of the earlier game of battledore and shuttlecock. ("Battledore" was an older term for "racquet".)[4] Its exact origin remains obscure. The name derives from the Duke of Beaufort's Badminton House in Gloucestershire,[5] but why or when remains unclear. As early as 1860, a London toy dealer named Isaac Spratt published a booklet entitled Badminton Battledore – A New Game, but no copy is known to have survived.[6] An 1863 article in The Cornhill Magazine describes badminton as "battledore and shuttlecock played with sides, across a string suspended some five feet from the ground".[7]

The game originally developed in India among the British expatriates,[8] where it was very popular by the 1870s.[6] Ball badminton, a form of the game played with a wool ball instead of a shuttlecock, was being played in Thanjavur as early as the 1850s[9] and was at first played interchangeably with badminton by the British, the woollen ball being preferred in windy or wet weather.

Early on, the game was also known as Poona or Poonah after the garrison town of Poona,[8][10] where it was particularly popular and where the first rules for the game were drawn up in 1873.[6][7][lower-alpha 2] By 1875, officers returning home had started a badminton club in Folkestone. Initially, the sport was played with sides ranging from 1 to 4 players, but it was quickly established that games between two or four competitors worked the best.[4] The shuttlecocks were coated with India rubber and, in outdoor play, sometimes weighted with lead.[4] Although the depth of the net was of no consequence, it was preferred that it should reach the ground.[4]

The sport was played under the Pune rules until 1887, when J. H. E. Hart of the Bath Badminton Club drew up revised regulations.[5] In 1890, Hart and Bagnel Wild again revised the rules.[6] The Badminton Association of England (BAE) published these rules in 1893 and officially launched the sport at a house called "Dunbar"[lower-alpha 3] in Portsmouth on 13 September.[12] The BAE started the first badminton competition, the All England Open Badminton Championships for gentlemen's doubles, ladies' doubles, and mixed doubles, in 1899.[5] Singles competitions were added in 1900 and an England–Ireland championship match appeared in 1904.[5]

England, Scotland, Wales, Canada, Denmark, France, Ireland, the Netherlands, and New Zealand were the founding members of the International Badminton Federation in 1934, now known as the Badminton World Federation. India joined as an affiliate in 1936. The BWF now governs international badminton. Although initiated in England, competitive men's badminton has traditionally been dominated in Europe by Denmark. Worldwide, Asian nations have become dominant in international competition. China, Denmark, Indonesia, Malaysia, India, South Korea, Taiwan (playing as 'Chinese Taipei') and Japan are the nations which have consistently produced world-class players in the past few decades, with China being the greatest force in men's and women's competition recently. Great Britain, where the rules of the modern game were codified, is not among the top powers in the sport, but has had significant Olympic and World success in doubles play, especially mixed doubles.

The game has also become a popular backyard sport in the United States.

Rules

The following information is a simplified summary of badminton rules based on the BWF Statutes publication, Laws of Badminton.[13]

Court

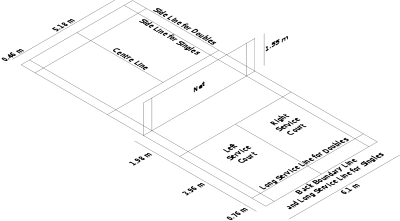

The court is rectangular and divided into halves by a net. Courts are usually marked for both singles and doubles play, although badminton rules permit a court to be marked for singles only.[13] The doubles court is wider than the singles court, but both are of the same length. The exception, which often causes confusion to newer players, is that the doubles court has a shorter serve-length dimension.

The full width of the court is 6.1 metres (20 feet), and in singles this width is reduced to 5.18 metres (17.0 feet). The full length of the court is 13.4 metres (44 feet). The service courts are marked by a centre line dividing the width of the court, by a short service line at a distance of 1.98 metres (6 feet 6 inches) from the net, and by the outer side and back boundaries. In doubles, the service court is also marked by a long service line, which is 0.76 metres (2 feet 6 inches) from the back boundary.

The net is 1.55 metres (5 feet 1 inch) high at the edges and 1.524 metres (5.00 feet) high in the centre. The net posts are placed over the doubles sidelines, even when singles is played.

The minimum height for the ceiling above the court is not mentioned in the Laws of Badminton. Nonetheless, a badminton court will not be suitable if the ceiling is likely to be hit on a high serve.

Serving

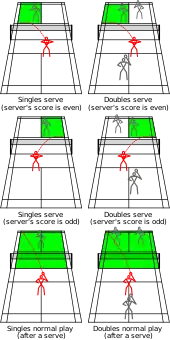

When the server serves, the shuttlecock must pass over the short service line on the opponents' court or it will count as a fault. The server and receiver must remain within their service courts, without touching the boundary lines, until the server strikes the shuttlecock. The other two players may stand wherever they wish, so long as they do not block the vision of the server or receiver.

At the start of the rally, the server and receiver stand in diagonally opposite service courts (see court dimensions). The server hits the shuttlecock so that it would land in the receiver's service court. This is similar to tennis, except that in a badminton serve the whole shuttle must be below 1.15 metres from the surface of the court at the instant of being hit by the server's racket, the shuttlecock is not allowed to bounce and in badminton, the players stand inside their service courts, unlike tennis.

When the serving side loses a rally, the server immediately passes to their opponent(s) (this differs from the old system where sometimes the serve passes to the doubles partner for what is known as a "second serve").

In singles, the server stands in their right service court when their score is even, and in their left service court when their score is odd.

In doubles, if the serving side wins a rally, the same player continues to serve, but he/she changes service courts so that she/he serves to a different opponent each time. If the opponents win the rally and their new score is even, the player in the right service court serves; if odd, the player in the left service court serves. The players' service courts are determined by their positions at the start of the previous rally, not by where they were standing at the end of the rally. A consequence of this system is that each time a side regains the service, the server will be the player who did not serve last time.

Scoring

Each game is played to 21 points, with players scoring a point whenever they win a rally regardless of whether they served[13] (this differs from the old system where players could only win a point on their serve and each game was played to 15 points). A match is the best of three games.

If the score ties at 20–20, then the game continues until one side gains a two-point lead (such as 24–22), except when there is a tie at 29–29, in which the game goes to a golden point of 30. Whoever scores this point wins the game.

At the start of a match, the shuttlecock is cast and the side towards which the shuttlecock is pointing serves first. Alternatively, a coin may be tossed, with the winners choosing whether to serve or receive first, or choosing which end of the court to occupy first, and their opponents making the leftover the remaining choice.

In subsequent games, the winners of the previous game serve first. Matches are best out of three: a player or pair must win two games (of 21 points each) to win the match. For the first rally of any doubles game, the serving pair may decide who serves and the receiving pair may decide who receives. The players change ends at the start of the second game; if the match reaches a third game, they change ends both at the start of the game and when the leading player's or pair's score reaches 11 points.

Lets

If a let is called, the rally is stopped and replayed with no change to the score. Lets may occur because of some unexpected disturbance such as a shuttlecock landing on a court (having been hit there by players playing in adjacent court) or in small halls the shuttle may touch an overhead rail which can be classed as a let.

If the receiver is not ready when the service is delivered, a let shall be called; yet, if the receiver attempts to return the shuttlecock, the receiver shall be judged to have been ready.

Equipment

Badminton rules restrict the design and size of racquets and shuttlecocks.

Racquets

Badminton racquets are lightweight, with top quality racquets weighing between 70 and 95 grams (2.5 and 3.4 ounces) not including grip or strings.[14][15] They are composed of many different materials ranging from carbon fibre composite (graphite reinforced plastic) to solid steel, which may be augmented by a variety of materials. Carbon fibre has an excellent strength to weight ratio, is stiff, and gives excellent kinetic energy transfer. Before the adoption of carbon fibre composite, racquets were made of light metals such as aluminium. Earlier still, racquets were made of wood. Cheap racquets are still often made of metals such as steel, but wooden racquets are no longer manufactured for the ordinary market, because of their excessive mass and cost. Nowadays, nanomaterials such as carbon nanotubes and fullerene are added to racquets giving them greater durability.

There is a wide variety of racquet designs, although the laws limit the racquet size and shape. Different racquets have playing characteristics that appeal to different players. The traditional oval head shape is still available, but an isometric head shape is increasingly common in new racquets.

Strings

Badminton strings for racquets are thin, high-performing strings with thicknesses ranging from about 0.62 to 0.73 mm. Thicker strings are more durable, but many players prefer the feel of thinner strings. String tension is normally in the range of 80 to 160 N (18 to 36 lbf). Recreational players generally string at lower tensions than professionals, typically between 80 and 110 N (18 and 25 lbf). Professionals string between about 110 and 160 N (25 and 36 lbf). Some string manufacturers measure the thickness of their strings under tension so they are actually thicker than specified when slack. Ashaway Micropower is actually 0.7mm but Yonex BG-66 is about 0.72mm.

It is often argued that high string tensions improve control, whereas low string tensions increase power.[16] The arguments for this generally rely on crude mechanical reasoning, such as claiming that a lower tension string bed is more bouncy and therefore provides more power. This is, in fact, incorrect, for a higher string tension can cause the shuttle to slide off the racquet and hence make it harder to hit a shot accurately. An alternative view suggests that the optimum tension for power depends on the player:[14] the faster and more accurately a player can swing their racquet, the higher the tension for maximum power. Neither view has been subjected to a rigorous mechanical analysis, nor is there clear evidence in favour of one or the other. The most effective way for a player to find a good string tension is to experiment.

Grip

The choice of grip allows a player to increase the thickness of their racquet handle and choose a comfortable surface to hold. A player may build up the handle with one or several grips before applying the final layer.

Players may choose between a variety of grip materials. The most common choices are PU synthetic grips or towelling grips. Grip choice is a matter of personal preference. Players often find that sweat becomes a problem; in this case, a drying agent may be applied to the grip or hands, sweatbands may be used, the player may choose another grip material or change their grip more frequently.

There are two main types of grip: replacement grips and overgrips. Replacement grips are thicker and are often used to increase the size of the handle. Overgrips are thinner (less than 1 mm), and are often used as the final layer. Many players, however, prefer to use replacement grips as the final layer. Towelling grips are always replacement grips. Replacement grips have an adhesive backing, whereas overgrips have only a small patch of adhesive at the start of the tape and must be applied under tension; overgrips are more convenient for players who change grips frequently, because they may be removed more rapidly without damaging the underlying material.

Shuttlecock

A shuttlecock (often abbreviated to shuttle; also called a birdie) is a high-drag projectile, with an open conical shape: the cone is formed from sixteen overlapping feathers embedded into a rounded cork base. The cork is covered with thin leather or synthetic material. Synthetic shuttles are often used by recreational players to reduce their costs as feathered shuttles break easily. These nylon shuttles may be constructed with either natural cork or synthetic foam base and a plastic skirt.

Badminton rules also provide for testing a shuttlecock for the correct speed:

3.1: To test a shuttlecock, hit a full underhand stroke that makes contact with the shuttlecock over the back boundary line. The shuttlecock shall be hit at an upward angle and in a direction parallel to the sidelines. 3.2: A shuttlecock of the correct speed will land not less than 530 mm and not more than 990 mm short of the other back boundary line.

Shoes

Badminton shoes are lightweight with soles of rubber or similar high-grip, non-marking materials.

Compared to running shoes, badminton shoes have little lateral support. High levels of lateral support are useful for activities where lateral motion is undesirable and unexpected. Badminton, however, requires powerful lateral movements. A highly built-up lateral support will not be able to protect the foot in badminton; instead, it will encourage catastrophic collapse at the point where the shoe's support fails, and the player's ankles are not ready for the sudden loading, which can cause sprains. For this reason, players should choose badminton shoes rather than general trainers or running shoes, because proper badminton shoes will have a very thin sole, lower a person's centre of gravity, and therefore result in fewer injuries. Players should also ensure that they learn safe and proper footwork, with the knee and foot in alignment on all lunges. This is more than just a safety concern: proper footwork is also critical in order to move effectively around the court.

Technique

Strokes

Badminton offers a wide variety of basic strokes, and players require a high level of skill to perform all of them effectively. All strokes can be played either forehand or backhand. A player's forehand side is the same side as their playing hand: for a right-handed player, the forehand side is their right side and the backhand side is their left side. Forehand strokes are hit with the front of the hand leading (like hitting with the palm), whereas backhand strokes are hit with the back of the hand leading (like hitting with the knuckles). Players frequently play certain strokes on the forehand side with a backhand hitting action, and vice versa.

In the forecourt and midcourt, most strokes can be played equally effectively on either the forehand or backhand side; but in the rear court, players will attempt to play as many strokes as possible on their forehands, often preferring to play a round-the-head forehand overhead (a forehand "on the backhand side") rather than attempt a backhand overhead. Playing a backhand overhead has two main disadvantages. First, the player must turn their back to their opponents, restricting their view of them and the court. Second, backhand overheads cannot be hit with as much power as forehands: the hitting action is limited by the shoulder joint, which permits a much greater range of movement for a forehand overhead than for a backhand. The backhand clear is considered by most players and coaches to be the most difficult basic stroke in the game, since the precise technique is needed in order to muster enough power for the shuttlecock to travel the full length of the court. For the same reason, backhand smashes tend to be weak.

Position of the shuttlecock and receiving player

The choice of stroke depends on how near the shuttlecock is to the net, whether it is above net height, and where an opponent is currently positioned: players have much better attacking options if they can reach the shuttlecock well above net height, especially if it is also close to the net. In the forecourt, a high shuttlecock will be met with a net kill, hitting it steeply downwards and attempting to win the rally immediately. This is why it is best to drop the shuttlecock just over the net in this situation. In the midcourt, a high shuttlecock will usually be met with a powerful smash, also hitting downwards and hoping for an outright winner or a weak reply. Athletic jump smashes, where players jump upwards for a steeper smash angle, are a common and spectacular element of elite men's doubles play. In the rearcourt, players strive to hit the shuttlecock while it is still above them, rather than allowing it to drop lower. This overhead hitting allows them to play smashes, clears (hitting the shuttlecock high and to the back of the opponents' court), and drop shots (hitting the shuttlecock softly so that it falls sharply downwards into the opponents' forecourt). If the shuttlecock has dropped lower, then a smash is impossible and a full-length, high clear is difficult.

Vertical position of the shuttlecock

When the shuttlecock is well below net height, players have no choice but to hit upwards. Lifts, where the shuttlecock is hit upwards to the back of the opponents' court, can be played from all parts of the court. If a player does not lift, their only remaining option is to push the shuttlecock softly back to the net: in the forecourt, this is called a net shot; in the midcourt or rear court, it is often called a push or block.

When the shuttlecock is near to net height, players can hit drives, which travel flat and rapidly over the net into the opponents' rear midcourt and rear court. Pushes may also be hit flatter, placing the shuttlecock into the front midcourt. Drives and pushes may be played from the midcourt or forecourt, and are most often used in doubles: they are an attempt to regain the attack, rather than choosing to lift the shuttlecock and defend against smashes. After a successful drive or push, the opponents will often be forced to lift the shuttlecock.

Spin

Balls may be spun to alter their bounce (for example, topspin and backspin in tennis) or trajectory, and players may slice the ball (strike it with an angled racquet face) to produce such spin. The shuttlecock is not allowed to bounce, but slicing the shuttlecock does have applications in badminton. (See Basic strokes for an explanation of technical terms.)

- Slicing the shuttlecock from the side may cause it to travel in a different direction from the direction suggested by the player's racquet or body movement. This is used to deceive opponents.

- Slicing the shuttlecock from the side may cause it to follow a slightly curved path (as seen from above), and the deceleration imparted by the spin causes sliced strokes to slow down more suddenly towards the end of their flight path. This can be used to create drop shots and smashes that dip more steeply after they pass the net.

- When playing a net shot, slicing underneath the shuttlecock may cause it to turn over itself (tumble) several times as it passes the net. This is called a spinning net shot or tumbling net shot. The opponent will be unwilling to address the shuttlecock until it has corrected its orientation.

Due to the way that its feathers overlap, a shuttlecock also has a slight natural spin about its axis of rotational symmetry. The spin is in a counter-clockwise direction as seen from above when dropping a shuttlecock. This natural spin affects certain strokes: a tumbling net shot is more effective if the slicing action is from right to left, rather than from left to right.[17]

Biomechanics

Badminton biomechanics have not been the subject of extensive scientific study, but some studies confirm the minor role of the wrist in power generation and indicate that the major contributions to power come from internal and external rotations of the upper and lower arm.[18] Recent guides to the sport thus emphasize forearm rotation rather than wrist movements.[19]

The feathers impart substantial drag, causing the shuttlecock to decelerate greatly over distance. The shuttlecock is also extremely aerodynamically stable: regardless of initial orientation, it will turn to fly cork-first and remain in the cork-first orientation.

One consequence of the shuttlecock's drag is that it requires considerable power to hit it the full length of the court, which is not the case for most racquet sports. The drag also influences the flight path of a lifted (lobbed) shuttlecock: the parabola of its flight is heavily skewed so that it falls at a steeper angle than it rises. With very high serves, the shuttlecock may even fall vertically.

Other factors

When defending against a smash, players have three basic options: lift, block, or drive. In singles, a block to the net is the most common reply. In doubles, a lift is the safest option but it usually allows the opponents to continue smashing; blocks and drives are counter-attacking strokes but may be intercepted by the smasher's partner. Many players use a backhand hitting action for returning smashes on both the forehand and backhand sides because backhands are more effective than forehands at covering smashes directed to the body. Hard shots directed towards the body are difficult to defend.

The service is restricted by the Laws and presents its own array of stroke choices. Unlike in tennis, the server's racquet must be pointing in a downward direction to deliver the serve so normally the shuttle must be hit upwards to pass over the net. The server can choose a low serve into the forecourt (like a push), or a lift to the back of the service court, or a flat drive serve. Lifted serves may be either high serves, where the shuttlecock is lifted so high that it falls almost vertically at the back of the court, or flick serves, where the shuttlecock is lifted to a lesser height but falls sooner.

Deception

Once players have mastered these basic strokes, they can hit the shuttlecock from and to any part of the court, powerfully and softly as required. Beyond the basics, however, badminton offers rich potential for advanced stroke skills that provide a competitive advantage. Because badminton players have to cover a short distance as quickly as possible, the purpose of many advanced strokes is to deceive the opponent, so that either they are tricked into believing that a different stroke is being played, or they are forced to delay their movement until they actually sees the shuttle's direction. "Deception" in badminton is often used in both of these senses. When a player is genuinely deceived, they will often lose the point immediately because they cannot change their direction quickly enough to reach the shuttlecock. Experienced players will be aware of the trick and cautious not to move too early, but the attempted deception is still useful because it forces the opponent to delay their movement slightly. Against weaker players whose intended strokes are obvious, an experienced player may move before the shuttlecock has been hit, anticipating the stroke to gain an advantage.

Slicing and using a shortened hitting action are the two main technical devices that facilitate deception. Slicing involves hitting the shuttlecock with an angled racquet face, causing it to travel in a different direction than suggested by the body or arm movement. Slicing also causes the shuttlecock to travel more slowly than the arm movement suggests. For example, a good crosscourt sliced drop shot will use a hitting action that suggests a straight clear or a smash, deceiving the opponent about both the power and direction of the shuttlecock. A more sophisticated slicing action involves brushing the strings around the shuttlecock during the hit, in order to make the shuttlecock spin. This can be used to improve the shuttle's trajectory, by making it dip more rapidly as it passes the net; for example, a sliced low serve can travel slightly faster than a normal low serve, yet land on the same spot. Spinning the shuttlecock is also used to create spinning net shots (also called tumbling net shots), in which the shuttlecock turns over itself several times (tumbles) before stabilizing; sometimes the shuttlecock remains inverted instead of tumbling. The main advantage of a spinning net shot is that the opponent will be unwilling to address the shuttlecock until it has stopped tumbling, since hitting the feathers will result in an unpredictable stroke. Spinning net shots are especially important for high-level singles players.

The lightness of modern racquets allows players to use a very short hitting action for many strokes, thereby maintaining the option to hit a powerful or a soft stroke until the last possible moment. For example, a singles player may hold their racquet ready for a net shot, but then flick the shuttlecock to the back instead with a shallow lift when they notice the opponent has moved before the actual shot was played. A shallow lift takes less time to reach the ground and as mentioned above a rally is over when the shuttlecock touches the ground. This makes the opponent's task of covering the whole court much more difficult than if the lift was hit higher and with a bigger, obvious swing. A short hitting action is not only useful for deception: it also allows the player to hit powerful strokes when they have no time for a big arm swing. A big arm swing is also usually not advised in badminton because bigger swings make it more difficult to recover for the next shot in fast exchanges. The use of grip tightening is crucial to these techniques, and is often described as finger power. Elite players develop finger power to the extent that they can hit some power strokes, such as net kills, with less than a 10 centimetres (4 inches) racquet swing.

It is also possible to reverse this style of deception, by suggesting a powerful stroke before slowing down the hitting action to play a soft stroke. In general, this latter style of deception is more common in the rear court (for example, drop shots disguised as smashes), whereas the former style is more common in the forecourt and midcourt (for example, lifts disguised as net shots).

Deception is not limited to slicing and short hitting actions. Players may also use double motion, where they make an initial racquet movement in one direction before withdrawing the racquet to hit in another direction. Players will often do this to send opponents in the wrong direction. The racquet movement is typically used to suggest a straight angle but then play the stroke crosscourt, or vice versa. Triple motion is also possible, but this is very rare in actual play. An alternative to double motion is to use a racquet head fake, where the initial motion is continued but the racquet is turned during the hit. This produces a smaller change in direction but does not require as much time.

Strategy

To win in badminton, players need to employ a wide variety of strokes in the right situations. These range from powerful jumping smashes to delicate tumbling net returns. Often rallies finish with a smash, but setting up the smash requires subtler strokes. For example, a net shot can force the opponent to lift the shuttlecock, which gives an opportunity to smash. If the net shot is tight and tumbling, then the opponent's lift will not reach the back of the court, which makes the subsequent smash much harder to return.

Deception is also important. Expert players prepare for many different strokes that look identical and use slicing to deceive their opponents about the speed or direction of the stroke. If an opponent tries to anticipate the stroke, they may move in the wrong direction and may be unable to change their body momentum in time to reach the shuttlecock.

Singles

Since one person needs to cover the entire court, singles tactics are based on forcing the opponent to move as much as possible; this means that singles strokes are normally directed to the corners of the court. Players exploit the length of the court by combining lifts and clears with drop shots and net shots. Smashing tends to be less prominent in singles than in doubles because the smasher has no partner to follow up their effort and is thus vulnerable to a skillfully placed return. Moreover, frequent smashing can be exhausting in singles where the conservation of a player's energy is at a premium. However, players with strong smashes will sometimes use the shot to create openings, and players commonly smash weak returns to try to end rallies.

In singles, players will often start the rally with a forehand high serve or with a flick serve. Low serves are also used frequently, either forehand or backhand. Drive serves are rare.

At high levels of play, singles demand extraordinary fitness. Singles is a game of patient positional manoeuvring, unlike the all-out aggression of doubles.[20]

Doubles

Both pairs will try to gain and maintain the attack, smashing downwards when the opportunity arises. Whenever possible, a pair will adopt an ideal attacking formation with one player hitting down from the rear court, and their partner in the midcourt intercepting all smash returns except the lift. If the rear court attacker plays a drop shot, their partner will move into the forecourt to threaten the net reply. If a pair cannot hit downwards, they will use flat strokes in an attempt to gain the attack. If a pair is forced to lift or clear the shuttlecock, then they must defend: they will adopt a side-by-side position in the rear midcourt, to cover the full width of their court against the opponents' smashes. In doubles, players generally smash to the middle ground between two players in order to take advantage of confusion and clashes.

At high levels of play, the backhand serve has become popular to the extent that forehand serves have become fairly rare at a high level of play. The straight low serve is used most frequently, in an attempt to prevent the opponents gaining the attack immediately. Flick serves are used to prevent the opponent from anticipating the low serve and attacking it decisively.

At high levels of play, doubles rallies are extremely fast. Men's doubles are the most aggressive form of badminton, with a high proportion of powerful jump smashes and very quick reflex exchanges. Because of this, spectator interest is sometimes greater for men's doubles than for singles.

Mixed doubles

In mixed doubles, both pairs typically try to maintain an attacking formation with the woman at the front and the man at the back. This is because the male players are usually substantially stronger, and can, therefore, produce smashes that are more powerful. As a result, mixed doubles require greater tactical awareness and subtler positional play. Clever opponents will try to reverse the ideal position, by forcing the woman towards the back or the man towards the front. In order to protect against this danger, mixed players must be careful and systematic in their shot selection.[21]

At high levels of play, the formations will generally be more flexible: the top women players are capable of playing powerfully from the back-court, and will happily do so if required. When the opportunity arises, however, the pair will switch back to the standard mixed attacking position, with the woman in front and men in the back.

Organization

Governing bodies

The Badminton World Federation (BWF) is the internationally recognized governing body of the sport responsible for the regulation of tournaments and approaching fair play. Five regional confederations are associated with the BWF:

- Asia: Badminton Asia Confederation (BAC)

- Africa: Badminton Confederation of Africa (BCA)

- Americas: Badminton Pan Am (North America and South America belong to the same confederation; BPA)

- Europe: Badminton Europe (BE)

- Oceania: Badminton Oceania (BO)

Competitions

The BWF organizes several international competitions, including the Thomas Cup, the premier men's international team event first held in 1948–1949, and the Uber Cup, the women's equivalent first held in 1956–1957. The competitions now take place once every two years. More than 50 national teams compete in qualifying tournaments within continental confederations for a place in the finals. The final tournament involves 12 teams, following an increase from eight teams in 2004. It was further increased to 16 teams in 2012.[22]

The Sudirman Cup, a gender-mixed international team event held once every two years, began in 1989. Teams are divided into seven levels based on the performance of each country. To win the tournament, a country must perform well across all five disciplines (men's doubles and singles, women's doubles and singles, and mixed doubles). Like association football (soccer), it features a promotion and relegation system at every level. However, the system was last used in 2009 and teams competing will now be grouped by world rankings.[23]

Badminton was a demonstration event at the 1972 and 1988 Summer Olympics. It became an official Summer Olympic sport at the Barcelona Olympics in 1992 and its gold medals now generally rate as the sport's most coveted prizes for individual players.

In the BWF World Championships, first held in 1977, currently only the highest-ranked 64 players in the world, and a maximum of four from each country can participate in any category. Therefore it's not an "open" format. In both the BWF World and the Olympic competitions restrictions on the number of participants from any one country have caused some controversy, because they result in excluding some world elite level players from the strongest badminton nations. The Thomas, Uber, and Sudirman Cups, the Olympics, and the BWF World (and World Junior Championships), are all categorized as level one tournaments.

At the start of 2007, the BWF introduced a new tournament structure for the highest level tournaments aside from those in level one: the BWF Super Series. This "level two" tournament series is a circuit for the world's elite players, staging twelve open tournaments around the world with 32 players (half the previous limit). The players collect points that determine whether they can play in Super Series Finals held at the year-end. Among the tournaments in this series is the venerable All-England Championships, first held in 1900, which was once considered the unofficial world championships of the sport.[24]

Level three tournaments consist of Grand Prix Gold and Grand Prix event. Top players can collect the world ranking points and enable them to play in the BWF Super Series open tournaments. These include the regional competitions in Asia (Badminton Asia Championships) and Europe (European Badminton Championships), which produce the world's best players as well as the Pan America Badminton Championships.

The level four tournaments, known as International Challenge, International Series, and Future Series, encourage participation by junior players.[25]

Comparison with tennis

Badminton is frequently compared to tennis due to several qualities. The following is a list of manifest differences:

- Scoring: In badminton, a match is played best 2 of 3 games, with each game played up to 21 points. In tennis a match is played best of 3 or 5 sets, each set consisting of 6 games and each game ends when one player wins 4 points or wins two consecutive points at deuce points. If both teams are tied at "game point", they must play until one team achieves a two-point advantage. However, at 29–all, whoever scores the golden point will win. In tennis, if the score is tied 6–6 in a set, a tiebreaker will be played, which ends once a player reaches 7 points or when one player has a two-point advantage.

- In tennis, the ball may bounce once before the point ends; in badminton, the rally ends once the shuttlecock touches the floor.

- In tennis, the serve is dominant to the extent that the server is expected to win most of their service games (at advanced level & onwards); a break of service, where the server loses the game, is of major importance in a match. In badminton, a server has far less an advantage and is unlikely to score an ace (unreturnable serve).

- In tennis, the server has two chances to hit a serve into the service box; in badminton, the server is allowed only one attempt.

- A tennis court is approximately twice the length and width of a badminton court.

- Tennis racquets are about four times as heavy as badminton racquets, 10 to 12 ounces (280 to 340 grams) versus 2 to 3 ounces (57 to 85 grams).[26][27] Tennis balls are more than eleven times heavier than shuttlecocks, 57 grams (2.0 ounces) versus 5 grams (0.18 ounces).[28][29]

- The fastest recorded tennis stroke is Samuel Groth's 163.4 miles per hour (263 kilometres per hour) serve,[30] whereas the fastest badminton stroke during gameplay was Mads Pieler Kolding's 264.7 miles per hour (426 kilometres per hour) recorded smash at a Badminton Premier League match.[31]

Statistics such as the smash speed, above, prompt badminton enthusiasts to make other comparisons that are more contentious. For example, it is often claimed that badminton is the fastest racquet sport.[32] Although badminton holds the record for the fastest initial speed of a racquet sports projectile, the shuttlecock decelerates substantially faster than other projectiles such as tennis balls. In turn, this qualification must be qualified by consideration of the distance over which the shuttlecock travels: a smashed shuttlecock travels a shorter distance than a tennis ball during a serve.

While fans of badminton and tennis often claim that their sport is the more physically demanding, such comparisons are difficult to make objectively because of the differing demands of the games. No formal study currently exists evaluating the physical condition of the players or demands during gameplay.

Badminton and tennis techniques differ substantially. The lightness of the shuttlecock and of badminton racquets allow badminton players to make use of the wrist and fingers much more than tennis players; in tennis, the wrist is normally held stable, and playing with a mobile wrist may lead to injury. For the same reasons, badminton players can generate power from a short racquet swing: for some strokes such as net kills, an elite player's swing may be less than 5 centimetres (2 inches). For strokes that require more power, a longer swing will typically be used, but the badminton racquet swing will rarely be as long as a typical tennis swing.

Notes

References

- Boga (2008).

- "Badminton – The Olympic Journey". Badminton World Federation Olympics. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- Grice (2008).

- EB (1878).

- EB (1911).

- Adams (1980).

- "badminton, n.", Oxford English Dictionary

- Guillain (2004), p. 47.

- "About Game", Ball Badminton Federation of India, 2008, archived from the original on 7 July 2011, retrieved 7 July 2011

- Connors, et al. (1991), p. 195.

- Downey (1982), p. 13.

- "The History of Badminton: Foundation of the BAE and Codification of the Rules", World Badminton

- "Laws of Badminton". Badminton World Federation. Archived from the original on 8 January 2017. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- Kwun (28 February 2005). "Badminton Central Guide to choosing Badminton Equipment". BadmintonCentral.com. Archived from the original on 11 March 2007.

- "SL-70". Karakal. Archived from the original on 16 October 2007.

- "String tension relating to power and control". Prospeed. Archived from the original on 28 October 2007.

- "The Spin Doctor". Power & Precision Magazine. July 2006.

- Kim (2002).

- "Badminton Technique", Badminton England "Videos / DVDS - Badminton England". Archived from the original on 17 April 2008. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- "Rules of Badminton". Retrieved 13 June 2017.

- Kumekawa, Eugene (21 March 2014). "Badminton Strategies and Tactics for the Novice and Recreational Player". BadmintonPlanet.

- "Thomas and Uber Cups increased to 16 teams". sportskeeda.com. 11 June 2012. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- Sachetat, Raphaël. "Sudirman Cup to Change Format". Badzine. Archived from the original on 31 January 2018. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- "Badminton Federation Announces 12-event Series", International Herald Tribune, Associated Press, 23 September 2006, archived from the original on 25 September 2015, retrieved 25 October 2008

- "New Tournament Structure", International Badminton Federation, 20 July 2006, archived from the original on 29 September 2007.

- "What is the ideal weight for a tennis racquet?". About.com. Archived from the original on 24 January 2009. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- "The contribution of technology on badminton rackets". Prospeed. Archived from the original on 11 October 2007.

- Azeez, Shefiu (2000). "Mass of a Tennis Ball". Hypertextbook.

- M. McCreary, Kathleen (5 May 2005). "A Study of the Motion of a Free Falling Shuttlecock" (PDF). The College of Wooster. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 June 2007.http://physics.wooster.edu/JrIS/Files/McCreary.pdf Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- "Aussie smashes tennis serve speed record". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- "Fastest badminton hit in competition (male)". Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- "WHAT IS BADMINTON". Badminton Oceania. Retrieved 18 February 2022.

Sources

- Adams, Bernard (1980), The Badminton Story, BBC Books, ISBN 0563164654

- Boga, Steve (2008), Badminton, Paw Prints, ISBN 978-1439504789

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911), , Encyclopædia Britannica, vol. 3 (11th ed.), Cambridge University Press, p. 189

- Connors, M.; Dupuis, D.L.; Morgan, B. (1991), The Olympics Factbook: A Spectator's Guide to the Winter and Summer Games, Visible Ink Press, ISBN 0-8103-9417-0.

- Downey, Jake (1982), Better Badminton for All, Pelham Books, ISBN 978-0-7207-1438-8.

- Grice, Tony (2008), Badminton: Steps to Success, Human Kinetics, ISBN 978-0-7360-7229-8

- Guillain, Jean-Yves (2004), Badminton: An Illustrated History, Publibook, ISBN 2-7483-0572-8

- Jones, Henry (1878), , in Baynes, T. S. (ed.), Encyclopædia Britannica, vol. 3 (9th ed.), New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, p. 228

- Kim, Wangdo (2002), An Analysis of the Biomechanics of Arm Movement During a Badminton Smash (PDF), Nanyang Technological University, archived from the original (PDF) on 2 October 2008.