Baganda music

Baganda music is a music culture developed by the people of Uganda with many features that distinguish African music from other world music traditions. Parts of this musical tradition have been extensively researched and well-documented, with textbooks documenting this research. Therefore, the culture is a useful illustration of general African music.

Musical instruments

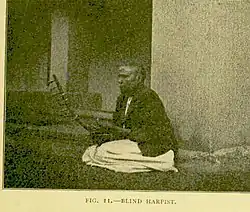

In addition to voice, a range of instruments are used, including the Amadinda, the Akadinda xylophones, the Ennanga harp, the Etongoli lyre, drums, and the Kadongo (plural "budongo") lamellophone.

Amadinda, akadinda, ennanga, and entongoli, as well as several types of drums, are used in the courtly music of the Kabaka, the king of Buganda. The kadongo, on the other hand, was more recently introduced to Baganda music, dating to the early 20th century. For this reason, budongo music is not part of the traditional court music.

Musical scale

Baganda music is based on an approximately equidistant pentatonic scale. Therefore, the octave (mwànjo, plural myanjo) is divided into five intervals of approximately 240 cents (2.4 semitones). There is some variation in the interval length between instruments, and it even might vary in one (tunable) instrument during a performance. This means that in an emic description, the scale can be called an equipentatonic scale while on an etic level of description, there might be different variations of implementing that conceptual scale.

Because this music is not harmony-based, chords are not used and only the octaves are consonant.

In Baganda culture, like in many African cultures, the musical scale is not perceived as pointing from "low" to "high" tones but the other way around, from "small" to "large" or "big" tones. Despite this, the notation (created by European ethnomusicologists) used for the music denotes the deepest tone as "1" and the highest as "5".

Timbre

As in many African cultures, there is a preference in Baganda music for "noisy" timbres. In the Kadongo lamellophone, metal rings are put around the lamellas to create a buzzing sound. In the ennanga harp, scales of a kind of goana are fixed on the instrument in such a way that the vibrating strings will touch it. This gives a crackling timbre to the sound. In tuning the instruments (including the xylophones), the octave is often deliberately not tuned exactly, resulting in an intended acoustic beat effect. In singing, "coarse" timbres are often used.

Form numbers

The music is generally repetitive. The elementary pulses in the music are quite fast. There are different form numbers, i.e., number of elementary pulses in one cycle, in Baganda music. Besides the more usual 24, 36 and 48 (multiples of 12), which are widespread in African music, there are also instances of unusual form numbers: the amadinda piece "Bakebezi bali e Kitende" has 50, the pieces "Ab'e Bukerere balaagira emwanyi" and "Akawologoma" have 54 and the piece "Agenda n'omulungi azaawa" has a rare form number of 70.

Inherent patterns

Much of the music is based on playing parallel octaves. For example, on the amadinda, two musicians play parallel octaves in an interlocking fashion, i.e. the tones played by one musician fall exactly between those played by the other musicians. Both musicians play parallel octaves, moving their right hand and left hand in parallel within a distance of five xylophone bars. In perception, neither the pattern played by one nor the pattern played by the other musician is perceived, and although the parallel octaves can be heard, they are hardly noticeable. Instead, perceptually, the music seems to consist of two to three pitch levels in which irregular melodic/rhythmic inherent patterns can be heard. The inherent patterns in the middle pitch level combine out of low pitch notes of the higher octave and high pitch notes of the lower octave. Generally, the patterns that can be heard are not played by any of the musicians but result from the combination of the actions of both musicians. Sometimes several conflicting ways of hearing patterns are present, and perception might switch between them. The musicians can influence this by accentuating certain notes.

Relationship between the instruments

There are close relationships between music of both the ennanga and entongoli, and the amadinda. Pieces for the string instruments can be translated to the xylophone. The part for the right hand is assigned to one musician and the part for the left hand is assigned to another. The ennanga has only eight strings, so parallel octaves can only be played within a restricted interval, but the general compositional principles applying to the xylophone music are the same in the chord instruments.

Music and language

Luganda is a tonal language. As with many other African musical cultures, the language significantly influences the music. The composer usually starts with the lyrics. The text's progression of tones partly determines the possible melodies of the song. He then composes a tune that fits the song's melodic pattern. When the music is played, inherent patterns may appear, which, to native speakers, may evoke new text associations. These might belong to totally different semantic areas, creating a strong poetic effect. Sometimes, such text associations "suggested" by the music are included in the sung text. However, they might be present for the Luganda speaker even if not made explicit in the text, adding an aesthetic level to the music that is only accessible to someone knowing conversant in the language.

The names of musical compositions often refer to the text that can be associated with the music. Moreover, mnemonic phrases are often used to memorize the sometimes long and irregular sequences of notes in xylophone playing.

Amadinda music

The instrument

The amadinda is a xylophone of the type called log xylophone. It consists of 12 wooden bars placed on two fresh banana stems. Sticks are inserted into the stems as separators between the bars. The bars are normally made from the wood of the Lusamba tree (Markhamia plarycalyx).

Basics of Amadinda playing

The amadinda (or madinda) is played by three musicians called omunazi, omwawuzi and omukoonezi, respectively. One of these sits on one side of the Xylophone, the other two on the other. Different seating arrangements are possible.

The music is always started by the omunazi. The omwawuzi then comes in, putting his notes exactly between those of the omunazi. The part of the omunazi is called okunaga, the part of the omwawuzi is called okwawula.

The following example shows the parts of the piece "Olutalo olw'e Nsinsi" (The battle of Nsinsi), a piece where the okwawula part is relatively simple. The form number of this piece is 24, i.e., one cycle has a total length of two times 12. Both musicians play parallel octaves on the first ten bars or the Amadinda, so in the following numerical notation, "1" means hitting the first (deepest) bar plus the sixth one together, and so on.

- Okunaga 4.3.4.3.3.3.4.3.4.4.2^2.

- Okwawula 5.2.1.5.2.1.5.2.1.5.2.1

The "^" denotes the place where the okwawula part starts—this entry point may be elsewhere in other compositions. The resulting sequence is 413542313532413542412522. This sequence is repeated, possibly many times.

The third musician, the omukoonezi, repeats the pattern occurring on the lowest two bars (the amatengezzi) two octaves higher on the highest two bars (the amakoonezi). The omukoonezi starts on the "2" of the okwawula. So, in this case, this pattern, called okukoonera is:

- 2.1...2.1...2.12.22..1...

The okukoonera is what would be heard on these two plates if the amadinda was extended by additional octaves played by another pair of omunazi and omwawuzi. So, one could also think of the omukoonezi of "simulating" the actions of two additional musicians. When listening to the music, one can perceive the okukoonera as a separate pattern, but it might also combine with notes played on the adjacent bars to form other audible patterns.

Playing techniques and terminology

The amadinda, like other types of south Ugandan Xylophones, is played by hitting the bars at the end with a stick. The tip of the bar is hit with the middle of the stick in an angle of about 45 degrees. The hands are moved in parallel. The movement should come from the wrist, and the arms should be moved as little as possible. The correct way of playing the amadinda is called Okusengejja, literally "to strain, to filter, to clarify, to sort things out". There are special techniques are used only by master players.

- Okudaliza (literally "to stitch a cloth together, to embroider") is a strongly accentuated way of playing. Certain tones are accentuated, bringing certain inherent patterns to the foreground. It is usually used to let the music culminate just before piece is finished.

- The term okusita ebiyondo oba ebisenge ("to erect corners or walls"—okusita meaning "to plait, to interweave (reed, fence etc.)" is an advanced playing technique in which certain notes are dropped out, resulting in a sudden change of the patterns one can hear.

There are several ways of playing Amadinda which are considered mistakes:

- In Okubwatula, the plates are hit on the top with the tip of the sticks. This is a common beginner's mistake. Literally, the word means a strong pain, especially in the bones.

- Okugugumula (literally "cause panic", "to rouse a flock of birds") is another beginner's mistake in which the hands are held stiffly and clumsily.

- Okuyiwa (literally "to put down", "to let down", "to disappoint") is an irregular way of playing in which the bars are not hit at the right moment.

- Okwokya (literally "to burn", "to roast") is a similar mistake in which the bars are hit too hastily.

Miko transpositions

Miko (singular Muko) are transpositions of a piece by one step of the scale (up or down). The whole melody is shifted up or down one xylophone bar: 1 is replaced by 2, 2 by 3, 3 by 4, 4 by 5 and 5 by 1. Although in the middle of the xylophone, the structure of the piece remains the same, the movement patterns of the musicians are changed, and the okukoonera part may become completely different. In fact, this way, from each piece of the total repertoire of 50 different compositions, 4 more pieces can be derived, giving a total of 250 pieces.

Repertoire

There are 50 different Amadinda pieces, not counting the miko transpositions. Their names are:

Form number 24 (2 x 12):

* Banno bakkola ng'osiga * Ndyegulira ekkadde * Ekyuma ekya Bora * Abaana ba Kalemba besibye bulungi * Segomba ngoye Mwanga alimpa * Ennyana ekutudde * Olutalo olw'e Nsisi * Wavvangaya * Omunyoro atunda nandere * Title unknown

Form number 36 (2 x 18):

* Ssematimba ne Kikwabanga * Naagenda kasana nga bulaba * Omusango gwa'abelere * Omuwabutwa wakyeejo * Mawasansa * Alifuledi * Omutamanya n'gamba * Katulye ku bye pesa * Ganga alula * Balangana enkonge * Byasi byabuna olugudo * Ab'e Busoga begaala ngabo * Nanjobe * Mugowa Iwatakiise * Gulemye Mpagala * Mawanda segwanga * Ebigambo ebibulire bitta enyumba * Walugembe eyava oKunywa * Omujooni: Balinserekerera balinsala ekyambe * Lutaaya yesse yekka * Kawumpuli * Abalung'ana be baleta engoye

Form number 48 (2 x 24):

* Atalabanga mudnu agende Buleega * Ezali embikke kasagazi kawunga * Kalagala e Bembwe * Semakookiro ne Jjunju * Agawuluguma ennyanja * Akaalo kekamu * Afa talamusa * Okuzanyira ku nyanja kutunda mwooyo * Ngabo Maanya eziriwangula Mugerere * Ensiriba ya munange Katego * Atakulubere * Nkejje namuwanula * Kansimbe omuggo awali Kibuka * Omukazi omunafu ngayigga na ngabo

Other form numbers (these form numbers are very unusual in African music):

* Bakebezi bali e Kitende form number 50 (2 x 25) * Ab'e Bukerere balaagira mwanyi form number 54 (2 x 27) * Akawologoma form number 54 (2 x 27) * Agenda n'omulungi azaawa form number 70 (2 x 35)

Numerical scores of all of these compositions have been published by Gerhard Kubik (s. References).

Comparison with other music cultures

Busoga (Embaire music)

The Embaire is the Xylophone played in Busoga sub-region.[1][2] The Embaire was described by Mark Stone, a lecturer at Oakland University and a former Rotary Ambassadorial Scholar at Makerere University during the 1996–1997 school year in these words: The Embaire is the most communal and most powerful xylophone tradition I know, a tradition that I am fortunate to teach regularly to my students at Oakland University in a number of classes[3][4]

Embaire keys are made from ensambiya wood (Bignoniaceae: Markhamia platycalyx),[5] and played by beating the ends of the keys with sticks from a heavier wood called enzo (Rutaceae: Teclea nobilis[6]). The keys are laid on felled banana stems, making an instrument which spans about 2.5m from end to end. The bass keys are large and broad but relatively thin. Wherever the instrument is played, a hole about 2 metres long and half a metre deep is first dug in the ground under the area where the bass keys will lie (the bottom ten keys of the Nakibembe instrument), to provide resonance: this chamber is sealed at the bottom end of the instrument with the base of a banana frond packed around with some of the excavated earth. In contrast to other parts of Uganda, Several impressive music groups with embaire xylophones are located relatively easily in Iganga district, Busoga.[7]

Parallels outside Uganda

Like the Amadinda music, the Timbrh (timbili) lamellophone music of the Vute of central Cameroon is based on playing parallel Octaves, resulting in inherent patterns. This striking similarity provides some evidence that the principles underlying both forms of music might go back to ancient times.

Recordings

- Evalisto Muyinda Music of the Baganda (1991)[8]

References

- Cooke, Peter (1970): "Ganda xylophone music - another approach", Journal of African Music, iv/4, 1970, p 62-75

- Cooke, Peter; Katamba, F (1987): "Ssematimba ne Kikwabanga : The music and poetry of a Ganda historical song", World of Music, xxix/2, 1987, p 49-68

- Cooke, Peter (1990, 2006): "Play Amadinda: Xylophone music from Uganda (Instructional cassette or CD and book), produced in collaboration with Albert Ssempeke, (for use both in East Africa and in multi-cultural education in UK, USA etc.) (Edinburgh 1990 - Revised 2006), 29pp. 31 audio examples.

- Cooke, Peter Teach yourself the Budongo (1988, 2006), (12-page booklet and cassette or CD), with C. Kizza, (produced for use both in Uganda and in multi-cultural education in UK, USA etc.), (Edinburgh,1988), 12pp. Revised 2006

- Kubik, Gerhard (1960) "The structure of Kiganda xylophone music" in African Music, 2 (3), pp. 6–30.

- Kubik, Gerhard (1969) "Composition techniques in Kiganda xylophone music" in African Music, 4 (3), pp. 22–72.

- Kubik, Gerhard "Die Amadinda-Musik von Buganda", in: Musik in Afrika. Hrsg. Arthur Simon, (Staatliche Museen) Berlin, 1983, S. 139-165 (contains numerical scores of all 50 pieces of the amadinda repertoire)

- Kubik, Gerhard "Kognitive Grundlagen afrikanischer Musik", in: Musik in Afrika. Hrsg. Arthur Simon, (Staatliche Museen) Berlin, 1983, S. 327-400

- Kubik, Gerhard "Xylophonspiel im Süden von Uganda" (1988). In: Kubik, Gerhard Zum Verstehen Afrikanischer Musik, Aufsätze, Reihe: Ethnologie: Forschung und Wissenschaft, Bd. 7, 2., aktualisierte und ergänzte Auflage, 2004, 448 S. ISBN 3-8258-7800-7 (in German language).

- Kubik, Gerhard "Theorie, Aufführungspraxis und Kompositionstechniken der Hofmusik von Buganda. Ein Leitfaden zur Komposition in einer ostafrikanischen Musikkultur", in: Für György Ligeti, Hamburg 1988, S. 23-162

- Simon, Artur (Ed.), "Musik in Afrika", (Staatliche Museen) Berlin 1983 (in German language, contains two musical cassettes including some Amadinda and ennanga examples played by Evalisto Muyinda)

External links

- Busoga sub-region

- Pier, David G., 1975- author. (25 October 2015). Ugandan music in the marketing era : the branded arena. ISBN 978-1-137-54939-6. OCLC 908286948.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Mark Stone - percussionist, composer, educator | Global Soundscapes | Embaire xylophone". markstonepercussion.com.

- "Mudondo - Embaire Xylophone at Oakland University". YouTube. Archived from the original on 2021-12-19.

- "Global Plants".

- "Global Plants".

- Micklem, James; Cooke, Andrew; Stone, Mark (1999). "Xylophone Music of Uganda: The Embaire of Nakibembe, Busoga". African Music. 7 (4): 29–46. doi:10.21504/amj.v7i4.1996. JSTOR 30249819.

- Baganda music at AllMusic