Bailo of Constantinople

A bailo, also spelled baylo (pl. baili / bailos) was a diplomat who oversaw the affairs of the Republic of Venice in Constantinople, the capital of the Ottoman Empire, and was a permanent fixture in the city around 1454.[1]

The traumatic outcomes of Venice's wars with the Ottomans made it clear to its rulers that in the Ottoman case the city would have to rely chiefly on diplomatic and political means rather than offensive military efforts to maintain and defend its position in the eastern Mediterranean. The bailo's job was very extensive because he was both Venice's political and foreign ambassador. He was very important in maintaining a good relationship between the Ottoman Sultan and the Venetian government. He was also there to represent and protect Venetian political interests. In Constantinople the bailo worked to solve any misunderstandings between the Ottomans and Venetians. To do this they established contacts and friendships with influential Ottomans and by doing this, they were able to protect their own interests. Unfortunately there were instances where there were difficulties finding replacements. This was often due to not enough qualified replacements, refusal to accept the position and the replacement dying before reaching Constantinople.[2]

Etymology

Like English bailiff, the Venetian word bailo derives from Latin baiulus, which originally meant "porter (carrier)". The Ottoman term was bālyōs or bālyoz.

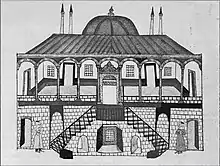

The bailate – the Venetian embassy

Sometime between the fall of Constantinople in 1453 and the outbreak of the Second Ottoman–Venetian War in 1499, the baili relocated to the center of Galata. After another war the bailo relocated to one of Galata’s suburbs, to an embassy called Vigne di Pera. This house was used as a summer home and as a refuge from the plague. After the War of Cyprus, the embassy in Galata relocated to Vigne di Pera permanently. Most baili preferred this location over the one in Galata because it had less restrictions in after-hours travel, and its location proved ideal in smuggling slaves.[3]

Vigne di Pera was a large complex surrounded by wall, with smaller complexes located inside. It had a large enough area to play ball in, a small chapel and housing quarters for the bailo’s postal carriers (to prevent the bailo from getting sick). There were two parts to the embassy, a public and private area. The private area housed the bailo, his company, his Janissary corps, and the secretarial staff. The public area was used as a receiving area for dignitaries and other important people, as well as a banquet hall for special occasions and parties.[3]

Functions, duties and responsibilities

One of the major responsibilities of the bailo was to collect information on the Ottoman Empire. They usually got this information though their wide networks of friends, their household and an informal spy network. This informal spy network consisted of moles: those who worked in the Imperial Arsenal in Galata, banished men and women, merchants and their associates and even people who worked within the Ottoman bureaucracy. The baili also set up moles in other foreign embassies.[4]

The bailo had the responsibility to promote and protect Venetian trade. This became the case after the Battle of Lepanto, when the bailo’s head ordered them to protect the integrity of their merchant powers from the English, Dutch and Florentines. The baili barely paid attention to commercial matters. saying it was too complicated to be bothered with, but every time there was a new sultan they made sure any agreements made with the previous sultan were followed though (this was made to protect Venetian citizens, goods and property, and this required a lot of attention from the bailo to make sure they were not being double crossed).[5]

Protecting the business interests of the Venetians involved in international commerce was also a function of the bailo. This was done especially if the person requested the bailo in settling debts with other people. They had to make sure business was good and were responsible for the Venetian subjects in Constantinople, especially if they died. Baili also acted as judges on the Venetian subjects because of their superior status. They usually presided over commercial and legal matters. Another responsibility was that he was in charge of all the trade in Ottoman lands and replacing consuls whenever he wanted to.[6]

The bailo was forbidden to actually do commerce such as trading themselves or represent other people commercially because situations might arise and fast become complicated and the bailo would be held accountable for whatever that person may have done; also, the integrity of the mission would become compromised. Although forbidden to engage in commercial acts, the bailos did so anyway.[7]

The life of a bailo

All of the baili were drawn from the ranks of the Venetian patriciate; this was a fundamental requirement, and most were drawn from the top tier of this oligarchy which dominated Venetian political life.[8]

Many baili did not marry[9] – this can be attributed to the fact that most held this position to give their family economic prestige, and had other male siblings who carried on the family name. The bailo was also involved in the Latin rite communities of the Ottoman Empire. They did things like getting churches that could be used by Venetians, and representing the Roman Catholics. The baili had active social lives and were present in confraternities, protected the company of the holy sacrament, patronized artists and artisans in the creation of religious objects and decorations for Latin-rite churches of Constantinople and Galata.[10]

One spiritual and diplomatic duty was to free Christian slaves unless they voluntarily converted to Islam. The major problem with this is that the bailo couldn’t release too many slaves or they would anger the sultan. The bailo actually had funds reserved for freeing slaves and, because of this, they were often accosted by many people asking for the bailo’s help. These funds either came out of their own pocket or from church donations from Venice.[11]

There were many reasons as to why many members of the patriciate did not want to become a bailo. There was a health risk associated with going to Constantinople – the long journey seemed to kill people and more seemed to be dying in the city itself. After several deaths during the voyage to Constantinople, the Venetian government allowed doctors to accompany the baili to keep them from dying. In case of hostilities, the baili were often in danger of being held hostage, but this was just a loose form of house arrest and the bailo was even allowed leave the house, especially if it was for religious purposes. It was rare that baili were executed, but the possibility of this happening was a further deterrent to holding this office.[12]

Money was hard to come by and most baili had to fund themselves. This was especially hard if they had no money in the first place. Often the bailo resorted to borrowing money from merchants, but this became increasing difficult as these merchants realized it took almost a year for the bailo to pay them back and started to refuse the bailo’s requests.[13]

Visit to Corfu

Giacomo Casanova mentions in his memoirs that during his stay in Corfu, the bailo of Constantinople, stopped on the island on his way to Constantinople aboard a 72-gun frigate named Europa. Having a greater rank than that of the Provveditore of Corfu, the flag of the bailo, bearing the colours of the captain-general of the Venetian Navy, was raised during his one-week stay on the island, while the flag with the colours of the Provveditore was lowered.[14]

References

- Goffman 2007, 71.

- Dursteler 2001, pp. 16–18.

- Dursteler 2006, pp. 25–27.

- Dursteler 2001, p. 3.

- Dursteler 2001, p. 4.

- Dursteler 2001, p. 5.

- Dursteler 2001, p. 6.

- Dursteler 2001, p. 9.

- Dursteler 2001, p. 12.

- Dursteler 2001, p. 7.

- Dursteler 2001, pp. 7–8.

- Dursteler 2001 pp. 16–18.

- Dursteler 2001, pp. 16–19.

- Giacomo Casanova; Arthur Machen (1894). The Memoirs of Jacques Casanova. pp. 10–11.

Bibliography

- Dursteler, Eric (2001). "The Bailo in Constantinople: Crisis and Career in Venice's Early Modern Diplomatic Corps". Mediterranean Historical Review. 16 (2): 1–30. doi:10.1080/714004583. S2CID 159980567.

- Dursteler, Eric (2006). Venetians in Constantinople. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Goffman, Daniel. “Negotiating with the Renaissance state: the Ottoman Empire and the new diplomacy” in The Early Modern Ottomans: Remapping the Empire. Ed. Virginia Aksan & Daniel Goffman. Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Further reading

- Arbel, B. Trading Nations – Jews and Venetians in the Early Modern Eastern Mediterranean. New York: E.J. Brill, Leiden, The Netherlands, 1995.

- Fabris, Antonio (1992). "From Adrianople to Constantinople: Venetian–Ottoman diplomatic missions, 1360–1453". Mediterranean Historical Review. 7 (2): 154–200. doi:10.1080/09518969208569639.

- Faroqhi, S (1986). The Venetian Presence in the Ottoman Empire (1600–1630). The Journal of European Economic History, 15(2), pg. 345-384.

- Goffman, Daniel. “Negotiating with the Renaissance state: the Ottoman Empire and the new diplomacy” in The Early Modern Ottomans: Remapping the Empire. Ed. Virginia Aksan & Daniel Goffman. Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- Nicol, Donald M. (1988). Byzantium and Venice: A Study in Diplomatic and Cultural Relations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-34157-4.

- Wirth, P. "Zum Verzeichnis Der Venezianischen Baili Von Konstantinopel." Byzantinische Zeitschrift, 54:2 (1961): 324–28.

- Guliyev, A. "Venice’s Knowledge of the Qizilbash – The Importance of the Role of the Venetian Baili in Intelligence-Gathering on the Safavids." Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 75.1 (2022) 79-97 https://doi.org/10.1556/062.2022.00116