Bananaquit

The bananaquit (Coereba flaveola) is a species of passerine bird in the tanager family Thraupidae. Before the development of molecular genetics in the 21st century, its relationship to other species was uncertain and it was either placed with the buntings and New World sparrows in the family Emberizidae, with New World warblers in the family Parulidae or its own monotypic family Coerebidae. This small, active nectarivore is found in warmer parts of the Americas and is generally common.

| Bananaquit | |

|---|---|

| |

| In Campo Limpo Paulista, São Paulo, Brazil | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Thraupidae |

| Genus: | Coereba Vieillot, 1809 |

| Species: | C. flaveola |

| Binomial name | |

| Coereba flaveola | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Its name is derived from its yellow color and the English word quit, which refers to small passerines of tropical America; cf. grassquit, orangequit.[2]

Taxonomy

The bananaquit was formally described by Carl Linnaeus in his landmark 1758 10th edition of Systema Naturae as Certhia flaveola.[3] Linnaeus based his description on the "black and yellow bird" described by John Ray and Hans Sloane,[4][5] and the "Black and Yellow Creeper" described and illustrated by George Edwards in 1751.[6] The bananaquit was reclassified as the only member of the genus Coereba by Louis Jean Pierre Vieillot in 1809.[7] The genus name is of uncertain origin but may be from a Tupi name Güirá for a small black and yellow bird. The specific epithet flaveolus is a diminutive of the Latin flavus meaning "golden" or "yellow".[8]

Before the development of techniques to sequence DNA, the relationship of the bananaquit to other species was uncertain. It was variously placed with the New World warblers in the family Parulidae,[9] with the buntings and New World sparrows in the family Emberizidae,[10] or in its own monotypic family Coerebidae.[11] Based on the results of molecular phylogenetic studies, the bananaquit is now placed in the tanager family Thraupidae and belongs with Darwin's finches to the subfamily Coerebinae.[12][13][14]

It is still unclear if any of the island subspecies should be elevated to species, but phylogenetic studies have revealed three clades: the nominate group from Jamaica, Hispaniola, and the Cayman Islands, the bahamensis group from the Bahamas and Quintana Roo, and the bartholemica group from South and Central America, Mexico (except Quintana Roo), the Lesser Antilles and Puerto Rico.[15][16] Several taxa were not sampled,[15][16] but most of these are easily placed in the above groups based on zoogeography alone. Exceptions are oblita (San Andrés Island) and tricolor (Providencia Island), and their placement is therefore uncertain. In February 2010, the International Ornithological Congress listed bahamensis and bartholemica as proposed splits from C. flaveola.[17]

Subspecies

There are 41 currently recognized subspecies:[14]

- C. f. bahamensis (Reichenbach, 1853): Bahamas

- C. f. caboti (Baird, 1873): east Yucatan Peninsula and nearby islands

- C. f. flaveola (Linnaeus, 1758): nominate, Jamaica

- C. f. sharpei (Cory, 1886): Cayman Is.

- C. f. bananivora (Gmelin, 1789): Hispaniola and nearby islands

- C. f. nectarea Wetmore, 1929: Tortue I.

- C. f. portoricensis (Bryant, 1866): Puerto Rico

- C. f. sanctithomae (Sundevall, 1869): north Virgin Is.

- C. f. newtoni (Baird, 1873): Saint Croix (south Virgin Is.)

- C. f. bartholemica (Sparrman, 1788): north and central Lesser Antilles

- C. f. martinicana (Reichenbach, 1853): Martinique and Saint Lucia (south central Lesser Antilles)

- C. f. barbadensis (Baird, 1873): Barbados

- C. f. atrata (Lawrence, 1878): St. Vincent (south Lesser Antilles)

- C. f. aterrima (Lesson, 1830): Grenada and the Grenadines (south Lesser Antilles)

- C. f. uropygialis von Berlepsch, 1892: Aruba and Curaçao (Netherlands Antilles)

- C. f. tricolor (Ridgway, 1884): Providencia I. (off east Nicaragua)

- C. f. oblita Griscom, 1923: San Andrés I. (off east Nicaragua)

- C. f. mexicana (Sclater, 1857): southeastern Mexico to western Panama

- C. f. cerinoclunis Bangs, 1901: Pearl Is. (south of Panama)

- C. f. columbiana (Cabanis, 1866): eastern Panama to southwestern Colombia and southern Venezuela

- C. f. bonairensis Voous, 1955: Bonaire I. (Netherlands Antilles)

- C. f. melanornis Phelps & Phelps, 1954: Cayo Sal I. (off Venezuela)

- C. f. lowii Cory, 1909: Los Roques Is. (off Venezuela)

- C. f. ferryi Cory, 1909: La Tortuga I. (off Venezuela)

- C. f. frailensis Phelps & Phelps, 1946: Los Frailes and Los Hermanos Is. (off Venezuela)

- C. f. laurae Lowe, 1908: Los Testigos (off Venezuela)

- C. f. luteola (Cabanis, 1850): coastal northern Colombia and Venezuela, Trinidad and Tobago

- C. f. obscura Cory, 1913: northeastern Colombia and western Venezuela

- C. f. minima (Bonaparte, 1854): eastern Colombia and southern Venezuela to French Guiana and north central Brazil

- C. f. montana Lowe, 1912: Andes of northwestern Venezuela

- C. f. caucae Chapman, 1914: western Colombia

- C. f. gorgonae Thayer & Bangs, 1905: Gorgona I. (off western Colombia)

- C. f. intermedia (Salvadori & Festa, 1899): southwestern Colombia, western Ecuador and northern Peru east to southern Venezuela and western Brazil

- C. f. bolivari Zimmer & Phelps, 1946: eastern Venezuela

- C. f. guianensis (Cabanis, 1850): southeastern Venezuela to Guyana

- C. f. roraimae Chapman, 1929: tepui regions of southeastern Venezuela, southwestern Guyana and northern Brazil

- C. f. pacifica Lowe, 1912: eastern Peru

- C. f. magnirostris (Taczanowski, 1880): northern Peru

- C. f. dispar Zimmer, 1942: north central Peru to western Bolivia

- C. f. chloropyga (Cabanis, 1850): east central Peru to central Bolivia and east to eastern Brazil, northern Uruguay, northeastern Argentina and Paraguay

- C. f. alleni Lowe, 1912: eastern Bolivia to central Brazil

Subspecies gallery

.jpg.webp) C. f. aterrima ("normal" and dark morph), Grenada

C. f. aterrima ("normal" and dark morph), Grenada.jpg.webp) C. f. bahamensis, Bahamas

C. f. bahamensis, Bahamas.jpg.webp) C. f. bartholemica, Guadeloupe

C. f. bartholemica, Guadeloupe_(8).jpg.webp) C. f. chloropyga, São Paulo, Brazil

C. f. chloropyga, São Paulo, Brazil C. f. flaveola, Jamaica

C. f. flaveola, Jamaica.jpg.webp) C. f. luteola, Trinidad

C. f. luteola, Trinidad.jpg.webp) C. f. mexicana, Costa Rica

C. f. mexicana, Costa Rica C. f. portoricensis, Puerto Rico

C. f. portoricensis, Puerto Rico C. f. sanctithomae, Saint John, U.S. Virgin Islands

C. f. sanctithomae, Saint John, U.S. Virgin Islands

Description

The bananaquit is a small bird, although there is some degree of size variation across the various subspecies. Length can range from 4 to 5 in (10 to 13 cm).[18][19] Weight ranges from 5.5 to 19 g (0.19 to 0.67 oz).[20][21]

Most subspecies of the bananaquit have dark grey (almost black) upperparts, black crowns and sides of the head, a prominent white eyestripe, grey throat, white vent, and yellow chest, belly, and rump. Coloration is heavily influenced by melanocortin 1 receptor variation.[22]

The sexes are alike, but juveniles are duller and often have partially yellow eyebrows and throat.

In the subspecies bahamensis and caboti from the Bahamas and Cozumel, respectively, the throat and upper chest are white or very pale grey,[23][24] while ferryi from La Tortuga Island has a white forehead.[25] The subspecies laurae, lowii, and melanornis from small islands off the coast of northern Venezuela are overall blackish,[25] while the subspecies aterrima and atrata from Grenada and Saint Vincent have two plumage morphs, one "normal" and another blackish.[23] The pink gape is usually very prominent in the subspecies from islands in the Caribbean Sea.

The tongue is paddle-shaped, with an extremely long paddle section.[26]

Distribution and habitat

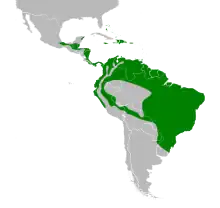

It is resident in tropical South America north to southern Mexico and the Caribbean. It is found throughout the West Indies, except for Cuba.[23] Birds from the Bahamas are rare visitors to Florida.[27]

It occurs in a wide range of open to semi-open habitats, including gardens and parks, but it is rare or absent in deserts, dense forests (e.g. large parts of the Amazon rainforest), and at altitudes above 2,000 m (6,600 ft).[25]

Behaviour and ecology

The bananaquit has a slender, curved bill, adapted to taking nectar from flowers, including mistletoes.[28] Nectivory is probably an independent innovation in Coereba.[26] Since then C. flaveola's tongue shape has shown convergent evolution with other birds feeding on the same flowers, and its source flowers have shown convergence to accommodate its tongue.[26] It sometimes pierces flowers from the side, taking the nectar without pollinating the plant - known as nectar robbing.[27][29] It also feeds on fruits - including mistletoe fruits and ripe bananas (hence the common name and bananivora for the Hispaniolan subspecies).[28][30][31] It has been observed taking fruits' sweet juices by puncturing fruit with its beak and it will also eat small insects (such as ants and flies), their larvae, and other small arthropods (such as spiders) on occasion.[32] While feeding, the bananaquit must always perch, as it cannot hover like a hummingbird.[30]

The bananaquit is known for its ability to adjust remarkably to human environments. It often visits gardens and may become very tame. Its nickname, the sugar bird, comes from its affinity for bowls or bird feeders stocked with granular sugar, a common method of attracting these birds.[30] The bananaquit builds a spherical lined nest with a side entrance hole, laying up to three eggs, which are incubated solely by the female.[33] It may also build its nest in human-made objects, such as lampshades and garden trellises. The birds breed all year regardless of season and build new nests throughout the year.[30]

References

- BirdLife International (2021). "Coereba flaveola". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2021: e.T22722080A137082125. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-3.RLTS.T22722080A137082125.en. Retrieved 14 December 2022.

- Reedman, R. (2016). Lapwings, Loons and Lousy Jacks: The How and Why of Bird Names. United Kingdom: Pelagic Publishing.

- Linnaeus 1758, p. 119.

- Ray, John (1713). Synopsis methodica avium & piscium (in Latin). Vol. Avium. London: William Innys. p. 187, No. 45.

- Sloane, Hans (1725). A Voyage to the Islands Madera, Barbados, Nieves, S. Christophers and Jamaica : with the natural history of the herbs and trees, four-footed beasts, fishes, birds, insects, reptiles, &c. of the last of those islands. Vol. 2. London: Printed for the author. p. 307, Plate 259 fig. 3.

- Edwards, George (1750). A Natural History of Uncommon Birds. Vol. Part 3. London: Printed for the author at the College of Physicians. p. 122, Plate 122.

- Vieillot 1809, p. 70.

- Jobling, James A. (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 113, 160. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- Paynter, Raymond A. Jr, ed. (1970). Check-List of Birds of the World. Vol. 13. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Museum of Comparative Zoology. p. 87.

- Committee on Classification and Nomenclature (1983). Check-list of North American Birds (6th ed.). Washington, DC: American Ornithologist's Union. p. 641. ISBN 0-943610-32-X.

- Committee on Classification and Nomenclature (1998). Check-list of North American Birds (PDF) (7th ed.). Washington, DC: American Ornithologist's Union. p. 569. ISBN 1-891276-00-X.

- Burns, K.J.; Hackett, S.J.; Klein, N.K. (2002). "Phylogenetic relationships and morphological diversity in Darwin's finches and their relatives". Evolution. 56 (6): 1240–1252. doi:10.1111/j.0014-3820.2002.tb01435.x. PMID 12144023.

- Burns, K.J.; Shultz, A.J.; Title, P.O.; Mason, N.A.; Barker, F.K.; Klicka, J.; Lanyon, S.M.; Lovette, I.J. (2014). "Phylogenetics and diversification of tanagers (Passeriformes: Thraupidae), the largest radiation of Neotropical songbirds". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 75: 41–77. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2014.02.006. PMID 24583021.

- Gill, Frank; Donsker, David; Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (July 2020). "Tanagers and allies". IOC World Bird List Version 10.2. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- Seutin et al. 1994

- Bellemain, Bermingham & Ricklefs 2008

- "Updates: Candidates". IOC World Bird List. Archived from the original on June 18, 2010. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- "Bananaquit". anywherecostarica.com. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- "Bananaquit". enature.com. Archived from the original on 19 March 2012. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- "Bananaquits". birdingguide.com. Archived from the original on 18 November 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- Diamond 1973

- Eizirik, Eduardo; Trindade, Fernanda J. (2021-02-16). "Genetics and Evolution of Mammalian Coat Pigmentation". Annual Review of Animal Biosciences. Annual Reviews. 9 (1): 125–148. doi:10.1146/annurev-animal-022114-110847. ISSN 2165-8102. PMID 33207915. S2CID 227065725.

- Raffaele et al. 1998

- Howell & Webb 1995

- Restall, Rodner & Lentino 2006

- Pauw, Anton (2019-11-02). "A Bird's-Eye View of Pollination: Biotic Interactions as Drivers of Adaptation and Community Change". Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics. Annual Reviews. 50 (1): 477–502. doi:10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-110218-024845. ISSN 1543-592X. S2CID 202854049.

- Dunning 2001

- Watson, David M. (2001). "Mistletoe—A Keystone Resource in Forests and Woodlands Worldwide". Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. Annual Reviews. 32 (1): 219–249. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.32.081501.114024. ISSN 0066-4162.

- Irwin, Rebecca E.; Bronstein, Judith L.; Manson, Jessamyn S.; Richardson, Leif (2010). "Nectar Robbing: Ecological and Evolutionary Perspectives". Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics. Annual Reviews. 41 (1): 271–292. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.110308.120330. ISSN 1543-592X.

- De Boer 1993, p. 105

- "Coereba flaveola (Bananaquit)". Animal Diversity Web.

- "Coereba flaveola (Bananaquit or Sugar Bird)" (PDF). The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago. Retrieved 12 April 2023.

- Monteiro Pereira 2008, p. 120

Literature cited

- Bellemain, Eva; Bermingham, Eldredge; Ricklefs, Robert E. (2008). "The dynamic evolutionary history of the bananaquit (Coereba flaveola) in the Caribbean revealed by a multigene analysis". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 8: 240. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-8-240. PMC 2533019. PMID 18718030.

- BirdLife International (2016). "Coereba flaveola". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T22722080A94747415. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22722080A94747415.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- Diamond, A. W. (1973). "Altitudinal variation in a resident and migrant passerine on Jamaica" (PDF). The Auk. 90 (3): 610–618. doi:10.2307/4084159. JSTOR 4084159.

- Dunning, John B. Jr (2001). "Bananaquit". In Elphick, Chris; Dunning, John B. Jr.; Sibley, David Allen (eds.). The Sibley Guide to Bird Life and Behavior. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 510–511. ISBN 978-1-4000-4386-6.

- Howell, S. N. G.; Webb, S. (1995). A Guide to the Birds of Mexico and Northern Central America. London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-854012-4.

- Linnaeus, C. (1758). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Editio decima, reformata (in Latin). Stockholm: Laurentius Salvius.

C. nigra, uropygio pectoreque luteo, superciliis macula alarum rectricumque apicibus albis.

- Monteiro Pereira, José Felipe (2008). Aves e Pássaros Comuns do Rio de Janeiro [Common Birds of Rio de Janeiro] (in Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro: Technical Books. ISBN 978-85-61368-00-5.

- De Boer, Bart A. (1993). Our Birds. Willemstad: Stichting Dierenbescherming Curaçao. ISBN 978-99904-0-077-9.

- Raffaele, Herbert; Wiley, James; Garrido, Orlando; Keith, Allan; Raffaele, Janis (1998). A Guide to the Birds of the West Indies. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-08736-8.

- Restall, R. L.; Rodner, C.; Lentino, M. (2006). Birds of Northern South America – An Identification Guide. London: Christopher Helm. ISBN 0-7136-7242-0.

- Seutin, G; Klein, N. K.; Ricklefs, R. E.; Bermingham, E. (1994). "Historical biogeography of the bananaquit (Coereba flaveola) in the Caribbean region: a mitochondrial DNA assessment". Evolution. 48 (4): 1041–1061. doi:10.2307/2410365. JSTOR 2410365. PMID 28564451.

- Vieillot, Louis Jean Pierre (1809). Histoire naturelle des oiseaux de l'Amérique septentrionale [Natural History of the Birds of Northern America] (in French). Paris: Desray.

Further reading

- Skutch, Alexander F. (1962). Life Histories of Central American Birds (PDF). Pacific Coast Avifauna, Number 31. Berkeley, California: Cooper Ornithological Society. pp. 404–420.

External links

- "Bananaquit media". Internet Bird Collection.

- Bananaquit Stamps (with range map) at bird-stamps.org

- Audio recordings of the Bananaquit on Xeno-canto.

- Bananaquit photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)

- Bananaquit species account at Neotropical Birds (Cornell Lab of Ornithology)

- Interactive range map of Coereba flaveola at IUCN Red List maps