Borgeet

Borgeets (Assamese: বৰগীত, romanized: Borgeet, lit. 'songs celestial') are a collection of lyrical songs that are set to specific ragas but not necessarily to any tala. These songs, composed by Srimanta Sankardeva and Madhavdeva in the 15th-16th centuries, are used to begin prayer services in monasteries, e.g. Satra and Namghar associated with the Ekasarana Dharma; and they also belong to the repertoire of Music of Meghalaya outside the religious context. They are a lyrical strain that express the religious sentiments of the poets reacting to different situations,[1] and differ from other lyrics associated with the Ekasarana Dharma.[2] Similar songs composed by others are not generally considered borgeets.

| Borgeet | |

|---|---|

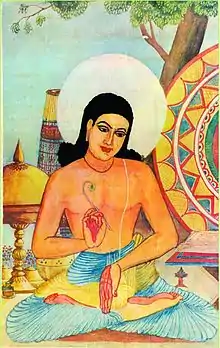

An imaginary portrait of Srimanta Sankardeva, the founder of Borgeet. | |

| Stylistic origins | Devotional song |

| Cultural origins | Early 1500s – late 1700s Assam, Neo-Vaishnavism |

| Typical instruments | Khol, Taal |

| Regional scenes | |

| Assam, India | |

| Local scenes | |

| Sattra, Namghar | |

| Other topics | |

| Hiranaam, Dihanaam, Bhaona, Ankia Naat, Katha Guru Charita | |

The first Borgeet was composed by Srimanta Sankardeva during his first pilgrimage at Badrikashram in c1488, which is contemporaneous to the birth of Dhrupad in the court of Man Singh Tomar (1486-1518) of Gwalior.[3] The Borgeets are written in Brajavali dialect that is distinct from the Brajabuli used in Orissa and Bengal—it is a language where Maithili inflections were added to Assamese vocables and poruniciations—[4] created by Shankardev and Madhabdev.

Lyrics

The borgeets are written in the pada form of verse. The first pada, marked dhrung,[5] works as a refrain and is repeated over the course of singing of the succeeding verses.[6] In the last couplet, the name of the poet is generally mentioned. The structure of borgeets is said to model the songs of 8-10th century Charyapada.[7]

The first borgeet, mana meri rama-caranahi lagu, was composed by the Sankardeva at Badrikashrama during his first pilgrimage. The language he used for all his borgeets is Brajavali, an artificial Maithili-Assamese mix; though Madhavdeva used Brajavali very sparingly.[8] Brajavali, with its preponderance of vowels and alliterative expressions, as considered ideal for lyrical compositions, and Sankardeva used it for borgeets and Ankia Naats.[9] Sankardeva composed about two hundred and forty borgeets, but a fire destroyed them all and only about thirty four of them could be retrieved from memory. Sankardeva, much saddened by this loss, gave up writing borgeets and asked Madhavdeva to write them instead.

Madhavdeva composed more than two hundred borgeets, which focus mainly on the child-Krishna.[10]

Music

The music of borgeets are based on ragas, which are clearly mentioned; and raginis, the female counterparts of ragas, are emphatically not used.[11] The rhythm (tala), on the other hand, are not mentioned; and borgeets need not be set to rhythm. Nevertheless, by convention tala is used when a borgeet is performed for an audience, or in a congregation, and in general specific ragas are associated with specific talas (e.g., Ashowari-raga with yati-maan; Kalyana-raga with khar-maan, etc.).[12] The lightness that is associated with the khyal type of Indian classical music is absent, instead the music is closer to the Dhrupad style. The singing of a borgeet is preceded by raga diya or raga tana, the local term for alap, but unlike the syllables used in Khyal or Dhrupad, words like Rama, Hari, Govinda, etc. are used.[13] Furthermore, raga diya is fixed as opposed to alap which is improvised.

The technique of Borgeet follows the Prabandhan Gana tradition which is contemporary to Dhrupad and Kriti of Hindustani and Carnatic music. In borgeets, there are Talas from eight matras to thirty-two matras, all comprising three parts of proportionate length, viz., Ga-man, Ghat and Cok. These Talas are different in structure, rhythmic pattern as well as playing style from the talas now played with Hindustani and Carnatic music. A few like Rupaka, Ektali, Yati, Bisam, etc. are mentioned not only in the Sangita Sastras like Sangita Ratnakara but also in Jayadeva’s Gita Govinda.[14]

Style

It is regarded that borgeets have been forming an indispensable part of Nama-Kirttana from the days of Sankardeva. The regular performance of Nama-Kirttana in Satra and Namghars is done by a single person called Nam-lagowa, where the Nam-lagowa first sings only the outline of a raga suitable for that time of the day, and sings a Borgeet or an Ankar git set in that raga without maintaining any beat, repeating the Dhrung or Dhruva after every couplet of the padas (subsequent verses). Such renderings of Borgeet are considered as a singing in Bak-sanchar (sheer voice-manipulation) or Melan (freedom from rhythmic restriction). The performance of Nama-Kirttana in early morning accompanied by the Khuti Taal is called a Manjira-prasanga. The Tal-kobowa prasanga performance which is accompanied by Bortaal can be rendered in both morning and dusk. Both the Manjira-prasanga and Tal-kobowa prasanga are played with borgeets. On occasions like Krishna Janmashtami, Doul, Bihu, death anniversaries (tithi) of religious preceptors including Sankardeva and Madhavdeva and during the whole month of Bhadra the performance of Borgeet is preceded by an orchestral recital of Khol, Taal, Negera (Percussion instrument) etc., which is variously referred to as Yora-prasanga, Khol-prasanga or Yogan-gowa. The orchestra comprises one or two pairs of Negera, Taal, Khols which are played in unison.[15][16]

Contemporary uses

The strict rules that are associated with the borgeets, and still practiced in the Sattras, are eschewed in popular renderings. A very knowledge Khol player and a renowned singer Khagen Mahanta has sung and documented some borgeets in its pure form in an album called Rajani Bidur. He was from the family of Satradhikars. He and his sister Nikunjalata Mahanta from the Gajala Satra were very well versed with this form. Borgeets were also used by Bhupen Hazarika,[17] in movies, and popular singers like Zubeen Garg have released their renderings.[18] Music director, Dony Hazarika has made a successful attempt to celebrate the Borgeet at the national level through his album, Bohnimaan...The folk flows.

Film critic and short film maker Utpal Datta made a short film on Borgeet, titled Eti Dhrupadi Ratna (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V3I5qgXt9G4) under the banner Pohar Media. Anupam Hazarika has produced the film. All leading exponents and artists were assembled for the film. Dr. Birendra Nath Datta, leading Satriya scholar, music director, singer and folklorist has narrated the content of the film while singer Gunindra Nath Ozah, Tarali Sarma, Sarod player Tarun Kalita, violin player Manoj Baruah and Satriya dancer Prerona Bhuyan has participated in the film with their arts to express various shades of the aesthetics of Borgeet.

Music director Anurag Saikia is known for taking an initiative of syncing borgeets to the symphonic orchestra.[19]

Translations

Borgeets have been translated into Hindi by Devi Prasad Bagrodia.[20]

References

- (Neog 1980, p. 178)

- The other forms lyrics are the bhatima (laudatory odes), kirtan- and naam-ghoxa (lyrics for congregational singing), ankiya geet (lyrics set to beats and associated with the Ankiya Naat), etc.

- (Sanyal & Widdness 2004, pp. 45–46)

- 'The Brajabuli idiom developed in Orissa and Bengal also. But as Dr Sukumar Sen has pointed out "Assamese Brajabuli seems to have developed through direct connection with Mithila" (A History of Brajabuli Literature, Calcutta, 1931 p1). This artificial dialect had Maithili as its basis to which Assamese was added.' (Neog 1980, p. 257f)

- is likely an abbreviation of Dhruva, the dhatu named in the Prabandha musical tradition (Mahanta 2008, p. 52)

- (Neog 1980, p. 278)

- (Barua 1953, p. 100)

- "Madhavdev did not use Brajabuli the way Sankardev did. If we dropped a few words, the language of most of Madhavdev's borgeets reduce to old Assamese" (Mahanta 2008, p. 15).

- (Barua 1953, pp. 98–100)

- (Sarma 1976, p. 60)

- (Neog 1980, p. 286)

- (Neog 1980, p. 278)

- (Neog 1980, p. 278)

- Rajan, Anjana (4 July 2019). "Should Borgeet of Assam be recognised as a classical art form?". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 14 September 2019.

- Bharatiya Prajna: an Interdisciplinary Journal of Indian Studies. Aesthetics Media Services. 2017. doi:10.21659/bp.

- B., E.; Prajnanananda, Swami (September 1961). "Historical Development of Indian Music". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 81 (4): 462. doi:10.2307/595734. ISSN 0003-0279. JSTOR 595734.

- Tejore Kamalapoti, by Madhavdeva, sung by Bhupen Hazarika (1955) Piyoli Phukan

- Pawe Pori Hori, by Shankardeva, sung by Zubeen Garg.

- "Project Borgeet: Syncing Assam's 600-year-old songs to the symphonic orchestra". The Indian Express. 13 September 2019. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- "The Assam Tribune Online". www.assamtribune.com. Archived from the original on 21 May 2014.

General sources

- Barua, B K (1953), "Sankaradeva: His Poetical Works", in Kakati, Banikanta (ed.), Aspects of Early Assamese Literature, Gauhati: Gauhati University

- Das-Gogoi, Hiranmayee (6 December 2011). "Dhrupadi Elements of Borgeet". Society for Srimanta Sankaradeva. Retrieved 23 October 2012.

- Mahanta, Bapchandra (2008). Borgeet (in Assamese) (2nd ed.). Guwahati: Students' Stores.

- Neog, Maheswar (1980), Early history of the Vaisnava faith and movement in Assam, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass

- Sanyal, Ritwik; Widdness, Richard (2004). Dhrupad: Tradition and Performance in Indian Music. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 9780754603795.

- Sarma, Satyendra Nath (1976), Assamese Literature, Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz