Bark bread

Bark bread is a traditional food made with cambium (phloem) flour. It has a history of use as famine food.

| |

| Type | Famine food, Bread |

|---|---|

| Place of origin | Scandinavia |

| Main ingredients | Flour, water, inner bark (e.g. phloem) of plants |

History

Bark bread seems to be a primarily Scandinavian tradition.[1] Bark bread is mentioned in medieval literature, and it may have an even older tradition among the Sami people, with the oldest findings of bark harvests being around 3000 years old.[2][3]

During the 18th and early 19th centuries, Northern Europe experienced several very bad years of crop failure, particularly during the Little Ice Age of the mid-18th century. The grain harvest was badly affected, and creative solutions to make the flour last longer were introduced. In 1742, samples of "emergency bread" were sent from Kristiansand, Norway, to the Royal Administration in Copenhagen, including bark bread, bread made from grainless husks and bread made from burned bones.[4] During the Napoleonic Wars, moss and lichen were used for human consumption.[5]

The last time bark bread was used as famine food in Norway was during the Napoleonic Wars. The introduction of the potato as a staple crop gave the farmers alternative crops when grain production failed, so that bark bread and moss cakes were no longer needed.[6] In Northern Sweden, traces of Sami harvest of bark from Scots pine are known from the 1890s, and, in Finland, pettuleipä (literally "pinewood-bark bread", made with cambium [phloem] flour) was eaten in Finland as an emergency food when there has been a shortage of food, especially during the Great Famine of the 1690s,[7] during the second famine of the 1860s, and, most recently, during the 1918 civil war.[3][8]

Examples of production

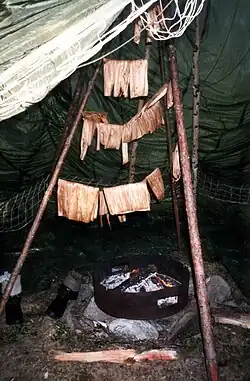

Finger-sized twigs and branches were collected from deciduous trees and shrubs, and the bark split and the inner bark (the phloem and sometimes the vascular cambium) collected while still fresh. The yellow or green inner bark (depending on tree species) was dried over open fires, in an oven, or in the sun. A mortar or mill was used to grind the bark to a fine powder to add to the flour. The dried bark pieces could also be added directly to the grain during milling. The bread was then baked the normal way adding yeast and salt.

Bark bread did not leaven as quickly as normal bread due to bark content. The more bark to flour, the slower the leavening. Bark bread was therefore often made as a flatbread. The bark flour could also be used for porridge.[9]

As food

The bark component was usually from deciduous trees like elm, ash, aspen, rowan or birch, but Scots pine and Iceland moss (sometimes named "bread moss" in Norwegian) are mentioned in historic sources. The inner bark is the only part of a tree trunk that is actually edible; the remaining bark and wood is made up of cellulose, which most animals, including humans, cannot digest. The dried and ground inner bark was added in proportions like 1/4th to 1/3rd "bark flour" to the remaining grain flour. Erik Pontoppidan, the bishop of Bergen, Norway in the mid-18th century, recommended using elm, as it helped the often crumbly bark bread hold together better.[10]

The bark will, however, add a rather bitter taste to the bread, and gives bread (particularly white bread) an unappetizing grey-green hue. Another problem is that the yeast cannot break down the ground bark; as a result, the bread will not leaven properly, and will be hard and not hold together well. Though bark today is sometimes added to pastries as a culinary curiosity, bark bread was considered an emergency food, and, as is common with such foods, was phased out as soon as the availability of grain improved.

The bark bread was seen as nutritionally deficient, more as "stomach filler" than as actual sustenance. Both the bishop Pontoppidan and others blamed the high mortality during the famine of the 1740s on the "unhealthy bark bread" and general lack of food.[4][10] Among the Sami, however, the bark and bark bread made from Scots pine served as an important source of vitamin C.[3]

References

- Vilhelm Moberg (1973). A History of the Swedish People. Stockholm: Norstedt.

- Forskning & Framsteg, Bark - nyttigt och gott!, ur nr 5/2007

- Zackrisson, O.; Östlund, L.; Korhonen, O.; Bergman, I. (2000), "The ancient use of Pinus sylvestris L. (scots pine) inner bark by Sami people in northern Sweden, related to cultural and ecological factors", Vegetation History and Archaeobotany, 9 (2): 99–109, doi:10.1007/bf01300060, S2CID 129174312, archived from the original on 2012-01-26, retrieved 2013-03-01

- "Bit av barkebrød Archived copy". Online exhibitions of the Norwegian National Archive (online). National Archives of Norway. Archived from the original on 5 April 2013. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- Gausmel, Steffen. "Gårdsdrift, dyrkingsmåter og avdrått". History of Lier commune (online). Lier kommune. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- Notaker, Henry (2006). Ganens makt: Norsk kokekunst og matkultur gjennom tusen år. Oslo: Aschehoug. ISBN 8203260098.

- Pauli Juusela (April 17, 2013). "Nälkä toi Suomeen kuolonvuodet. Nälänhätä". valomerkki.fi (in Finnish). Archived from the original on August 15, 2016. Retrieved October 1, 2020.

- Mäkinen, R. (15 November 2006). "The near-famine in Finland 1917-1918: the State Committee for Household Counselling and other consequences" (PDF). Talks at the XIV International Economic History Congress. International Economic History Association. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- "Uppteckningar gällande Nödåren" Archived December 28, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, (in Swedish) told by Augusta Karlsson, born 1856

- Pontoppidan, E. (1752/1753): Forsøk til Norges naturlige historie (Attempt at the Natural History of Norway). Vol I and II.