Barrios of Puerto Rico

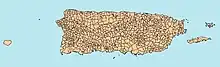

The barrios of Puerto Rico are the primary legal divisions of the seventy-eight municipalities of Puerto Rico.[1] Puerto Rico's 78 municipios are divided into geographical sections called barrios (English: "wards") and, as of 2010, there were 902 of them.[2][3] In the US Census a barrio sometimes includes a division called a comunidad or subbarrio. In Puerto Rico, barrios are composed of sectors. The types of sectors, (sectores) may vary, from normally sector to urbanización to reparto to barriada to residencial, among others.

History

The history of the creation of the barrios of Puerto Rico can be traced to the 19th century, when historical documents first mention them. Historians have speculated that their creation may have been related to the Puerto Rican representation at the Cortes of Cádiz.[4] The names of barrios in Puerto Rico come from various sources, mostly from Spanish or Indian origin.[5][6][7][8] One barrio in each municipality (except for Florida, Ponce, and San Juan) is identified as the barrio-pueblo. It is differentiated from other barrios in that it is the historical center of the municipality and the area that represented the seat of the municipal government at the time Puerto Rico formalized the municipio and barrio boundaries in the late 1940s.[9][10] From time to time barrios are created, broken up, or merged.[11][12] The downtown district of each town was called pueblo until 1990, when they began to be referred to as barrio-pueblo in the US Census, and contains the plaza, municipal buildings and a Roman Catholic church.[13]

In 1832 there were 490, in 1878 there were 841, in 1990 there were 899 barrios.[14]

Classification

.jpg.webp)

The United States Census Bureau recognizes 902 barrios in Puerto Rico.[15][16] The US classifies barrios as minor civil divisions for statistical purposes.[17] As components of each municipality, each municipality has one or more barrios. Every municipality has at least one barrio called barrio Pueblo which is home to the largest urban area of the municipality, and the political seat of the municipality.[18] Most municipalities have a single barrio named barrio Pueblo while others, most prominently the larger municipalities like the municipality of Ponce, may have a barrio Pueblo that is made of several barrios. Florida is the municipality with the fewest barrios,[19] while Ponce, at 31, has the most.[20]

The US Census Bureau further breaks down some barrios in Puerto Rico into subbarrios. One such example is Santurce (in San Juan) which has 40 subbarrios. Another example is barrio Segundo in Ponce which consists of subbarrios Clausells and Baldorioty de Castro (commonly shortened to Baldorioty).[21] With over 24 square miles (62 km2), barrio Lapa in the northeast area of the municipality of Salinas, has the largest territorial area of any barrio in Puerto Rico,[22] being larger in size than 10 of Puerto Rico's municipalities.

Another subdivision that may exist within a barrio is a comunidad, as seen in Census data. Esperanza is a comunidad in Vieques and an example of a subdivision of a barrio which is not called a subbarrio but is called instead a comunidad.[23] Outside of the Census data and in Puerto Rico barrios are divided by sectors. Municipios list their barrios and the sectors within them. Cañaboncito barrio in Caguas, for example, has over 90 sectors. The types of sectors, (sectores) may vary, from normally sector to urbanización to reparto to barriada to residencial, among others.[24]

Significance

While in the past, barrios in Puerto Rico had political authority, each with their own elected mayor[25][26] and "barrio councils", currently barrios in Puerto Rico are no longer vested with any political authority. Their purpose was originally for the collection of taxes,[27] but during the 1800s any political authority barrios had been centralized in the municipal governments. In 1880 Spain's Nomenclature of its Territories publication, it is stated that the municipalities were subdivided, as needed, to facilitate voting and to ease the administration of each municipality.[28] An analysis of the 1899 Puerto Rican and Cuban census, published by the War Department and Inspector General of the United States in 1900 listed the census population numbers by barrios of Puerto Rico.[29]

Barrio names continue to be an essential point of reference for purposes of municipal and state government property management, including land surveying and property sale, purchase, and ownership.[30] Land and property deeds and surveys are all performed with barrio names as a mandatory reference. For example, official legal matters dealing with land and property issues are heard on the basis of municipal locations relative to the officially recognized barrios and barrio boundaries.[31]

Problems

Non-official usage

The 902 barrios of Puerto Rico represent officially established primary legal divisions of the seventy-eight municipalities that contain unique and permanent geographical land boundaries. Puerto Rico Act 68 of 7 May 1945 (Ley Num. 68 de 7 de mayo de 1945), ordered the commonwealth's Planning Board to prepare a map of each of the municipalities and each of the barrios within said municipalities and the corresponding barrio names. Said map and list of barrio names constitute the officially established primary legal barrio divisions.[32]

However, often the word "barrio" is also (mistakenly) used in Puerto Rico in an unofficial manner to represent a populated sector within a barrio, and in this latter case the name of the sector can be—and most often is—different from the official barrio where it is located. An example of this non-official usage is the reference to Puerto Rican nationalist Don Pedro Albizu Campos as having been born in barrio Tenerias in Ponce[33][34][35] yet, there has never been a barrio Tenerias in Ponce;[36] Tenerias is a populated sector—a settlement—of barrio Machuelo Abajo.[37] The problem is that populated places have been adopting names for themselves that do not appear in the official government maps, because such maps have not been updated, and there is no system in place for such updates.[38]

Quality control and GPS plotting

Puerto Rico barrio boundaries were established using landmarks such as "the top of a mountain", "the lot owned by Franscico Mattei", "the peak of a mountain ridge", "an almond tree" (árbol de húcar), and "to origin of Loco River".[lower-alpha 1] When describing the boundaries of Las Piedras, the official 1952 document by the Puerto Rico Planning Board stated "the border continues through Cándido Márquez's and Jesús Barrio's farms until reaching a mamey tree. This tree is about 50 meters south of Leoncio Rivera's home..."[39] As these descriptors tended to lend themselves to ambiguity and other problems, there was a 2002 initiative by the University of Puerto Rico to describe boundaries using GPS technology.[40] The GPS coordinates of barrios of Puerto Rico are available via a Puerto Rico government portal.[41]

See also

Notes

- For numerous examples of this usage, see "Mapa de Municipios y Barrios: Ponce, Memoria Num. 27." Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico. Oficina del Gobernador. Junta de Planificacion. Santurce, Puerto Rico. Rafael Pico, Presidente. 1953.

References

- Cartographic Boundary Files: 2000 County Subdivisions. Archived 2013-05-10 at the Wayback Machine U. S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- Municipalities of Puerto Rico. Archived 2011-12-03 at the Wayback Machine Gwillim Law. 2011. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- Rafael Picó (1969). Nueva geografía de Puerto Rico: física, económica, y social. Nueva geografía de Puerto Rico: física, económica, y social. p. 247.

- Los alcaldes de los barrios. Archived 2014-04-13 at the Wayback Machine Rafael Torrech San Inocencio. "Barrios del Sur." El Sur a la Vista. Ponce, Puerto Rico. 16 January 2011. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- Barrios boricuas con nombres raros. Archived 2011-09-10 at the Wayback Machine El Nuevo Dia. San Juan, Puerto Rico. 19 June 2011. Retrieved 7 December 2011.

- El legado indígena en los nombres de nuestros barrios. Archived 2013-09-22 at the Wayback Machine Rafael Torrech San Inocencio. "Barrios del Sur." El Sur a la Vista. Ponce, Puerto Rico. 10 October 2010. Retrieved 5 December 2011.

- Un Acercamiento Sociohistorico y Linguistico a los Toponimos del Municipio de Ponce, Puerto Rico. Archived 2016-11-26 at the Wayback Machine Amparo Morales, María T. Vaquero de Ramírez. "Estudios de lingüística hispánica: homenaje a María Vaquero". Page 113. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- Hacia un Estudio Integral de la Toponimia del Municipio de Ponce, Puerto Rico. Sunny A. Cabrera Salcedo. Ph.D. dissertation. May 1999. University of Massachusetts Amherst. Graduate School. Department of Spanish and Portuguese. Page 21.

- History, 2000 Census of population and housing, p. 400, at Google Books, U.S. Dept. of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, U.S. Census Bureau, 2009

- Cartographic Boundary Files. Archived 2013-05-10 at the Wayback Machine U. S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- Ley Núm. 77 del año 2009: Para separar el Sector Certenejas del Barrio Bayamón del Municipio Autónomo de Cidra y denominarlo como el Barrio Certenejas. Ley Núm. 77 de 16 de agosto de 2009. Archived 2012-04-05 at the Wayback Machine Puerto Rico House of Representatives. House Bill Number 1028; Act 77 of 2009. (P. de la C. 1028. Year 2009. Ley 77). Legislative Assembly of Puerto Rico. San Juan, Puerto Rico. 16 August 2009. LexJuris Puerto Rico. Retrieved 6 December 2011.

- Ciales... La Ciudad de la Cojoba. Archived 2012-04-22 at the Wayback Machine Boricua Online. 2011. Retrieved 6 December 2011.

- Mari Mut, José A. (28 August 2013). "Los pueblos de Puerto Rico y las iglesias de sus plazas [Puerto Rico's pueblos and its plaza churches]" (in Spanish). Retrieved 9 September 2020 – via archive.org.

- Inocencio, Rafael Torrech San (December 1, 2017). "LOS BARRIOS DE PUERTO RICO". Academia.edu (in Spanish). Archived from the original on August 24, 2022. Retrieved August 24, 2022.

- Barrios boricuas con nombres raros. Archived 2011-09-10 at the Wayback Machine El Nuevo Dia. San Juan, Puerto Rico. 19 June 2011. Retrieved 7 December 2011.

- El rastro de los primeros colonizadores en nuestros barrios. Archived 2018-12-26 at the Wayback Machine Rafael Torrech San Inocencio. El Sur a la Vista. Ponce, Puerto Rico. 14 November 2010. Retrieved 7 December 2011.

- "US Census Barrio-Pueblo definition". factfinder.com. US Census. Archived from the original on 13 May 2017. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- Hacia un Estudio Integral de la Toponimia del Municipio de Ponce, Puerto Rico. Sunny A. Cabrera Salcedo. Ph.D. dissertation. May 1999. University of Massachusetts Amherst. Graduate School. Department of Spanish and Portuguese. Page 33.

- Perfil Demográfico por Municipio, Censo 2000. Archived 2011-08-23 at the Wayback Machine Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico. Junta De Planificacion. Oficina del Censo. San Juan, Puerto Rico. 3 September 2010. (C)2011. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- Historia de Nuestros Barrios: Portugués, Ponce. Archived September 3, 2014, at the Wayback Machine Rafael Torrech San Inocencio. El Sur a la Vista. elsuralavista.com. 14 February 2010. Accessed 1 December 2011.

- Cartographic Boundary Files. Archived 2013-05-10 at the Wayback Machine U. S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- Historia de nuestros barrios: Lapa, Salinas. Archived 2012-03-12 at the Wayback Machine Rafael Torrech San Inocencio. In, "Barrios del Sur". El Sur a la Vista. Ponce, Puerto Rico. 26 December 2009. Retrieved 7 December 2011.

- Puerto Rico:2010:population and housing unit counts.pdf (PDF). U.S. Dept. of Commerce Economics and Statistics Administration U.S. Census Bureau. 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-02-20. Retrieved 2018-12-28.

- "Lista Sectores por Barrio Separados" (PDF). caguas.gov.pr (in Spanish). Municipio Autónomo de Caguas Oficina de Planificación Unidad de Información Geográfica y Estadísticas Vitales. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 August 2022. Retrieved 15 October 2022.

- Los alcaldes de los barrios. Archived 2014-04-13 at the Wayback Machine Rafael Torrech San Inocencio. "Barrios del Sur." El Sur a la Vista. Ponce, Puerto Rico. 16 January 2011. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- Our landless patria: marginal citizenship and race in Caguas, Puerto Rico. (1880–1910) Archived 2016-12-24 at the Wayback Machine Rosa E. Carrasquillo. University of Nebraska. Lincoln, Nebraska. 2006. Page 160. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- Los alcaldes de los barrios. Archived 2014-04-13 at the Wayback Machine Rafael Torrech San Inocencio. "Barrios del Sur." El Sur a la Vista. Ponce, Puerto Rico. 16 January 2011. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- División territorial de Puerto Rico y nomenclator de sus poblaciones (1880). Madrid; Imprenta de la viuda e hija de Peñuelas, 1880. pp. 4–6. Archived from the original on 22 July 2021. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- Joseph Prentiss Sanger; Henry Gannett; Walter Francis Willcox (1900). Informe sobre el censo de Puerto Rico, 1899, United States. War Dept. Porto Rico Census Office (in Spanish). Imprenta del gobierno. p. 160.

- Teissonier v. Barnes. Appeal from the District Court of Ponce. No. 37. Decided 23 March 1905. In, "Report of Cases Adjudged in the Supreme Court of Puerto Rico. January 23 to June 17, 1905." Coleccion de las sentencias y resoluciones dictadas por el Tribunal. Volumen 8. Published by the Puerto Rico Supreme Court. Antonio F. Castro, Rafael Hernandez-Usera, Raleigh F. Haydon, Pablo Berga y Ponce de León, Joaquín López. Pages 196-205. Printed by the Bureau of Supplies, Printing and Transportation. Published by the Supreme Court of Puerto Rico. San Juan, Puerto Rico. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- 765 F.2d 275. Archived 2012-04-07 at the Wayback Machine Gloria J. ORTIZ DE ARROYO, et al., v. Carlos Romero BARCELO, etc., et al. No. 84-1132. United States Court of Appeals, First Circuit. Argued Feb. 4, 1985. Decided June 26, 1985. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- Proyecto del Senado 220. 13 de Enero de 2009. Archived 2018-12-26 at the Wayback Machine Senator Luis D. Muñiz Cortés. Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico. Senado de Puerto Rico. 13 de enero de 2009. Page 1. Retrieved 6 December 2011.

- Celebrarán natalicio de Pedro Albizu Campos. El Nuevo Dia. San Juan, Puerto Rico. 6 September 2011. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- Albizu Campos, Pedro. Archived 2012-04-05 at the Wayback Machine LexJuris Biographies. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- Mis Mejores temas. Archived 2010-07-27 at the Wayback Machine Prof. José Juan Báez Fumero. "Horizontes." Dept. Estudios Hispánicos. Pontificia Universidad Católica de Puerto Rico. Page 137. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- Barrios de Ponce. Archived 2012-04-25 at the Wayback Machine Government of the Autonomous Municipality of Ponce. Ponce, Puerto Rico. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- Beyond the archives: research as a lived process. Gesa Kirsch, Liz Rohan. Southern Illinois University. 2008. Page 87. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- Proyecto del Senado 220. 13 de Enero de 2009. Archived 2018-12-26 at the Wayback Machine Senator Luis D. Muñiz Cortés. Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico. Senado de Puerto Rico. 13 de enero de 2009. Page 2. Retrieved 6 December 2011.

- Memoria 28 Las Piedras 1952 (PDF) (in Spanish). University of Puerto Rico: junta de planificacion de puerto rico. pp. 8–9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 July 2021. Retrieved 22 July 2021.

- Límites de Municipios y Barrios a Establecerse con GPS. Archived 2012-04-26 at the Wayback Machine Linda L. Vélez Rodríguez. Department of Civil Engineering and Land Surveying. University of Puerto Rico at Mayaguez. Mayagüez, Puerto Rico. Retrieved 6 December 2011.

- "gis.pr.gov". Home-Portal gis.pr.gov-Inicio (in Spanish). 2021-07-21. Archived from the original on 2021-04-21. Retrieved 2021-07-21.