Basilideans

The Basilidians or Basilideans /ˌbæsɪˈlɪdiənz, ˌbæz-/ were a Gnostic sect founded by Basilides of Alexandria in the 2nd century. Basilides claimed to have been taught his doctrines by Glaucus, a disciple of St. Peter, though others stated he was a disciple of the Simonian Menander.

|

Of the customs of the Basilidians, we know no more than that Basilides enjoined on his followers, like Pythagoras, a silence of five years; that they kept the anniversary of the day of the baptism of Jesus as a feast day[1] and spent the eve of it in reading; that their master told them not to scruple eating things offered to idols. The sect had three grades – material, intellectual and spiritual – and possessed two allegorical statues, male and female. The sect's doctrines were often similar to those of the Ophites and later Jewish Kabbalah.

Basilidianism survived until the end of the 4th century as Epiphanius knew of Basilidians living in the Nile Delta. It was however almost exclusively limited to Egypt, though according to Sulpicius Severus it seems to have found an entrance into Spain through a certain Mark from Memphis. St. Jerome states that the Priscillianists were infected with it.

Cosmogony of Hippolytus

The descriptions of the Basilidian system given by our chief informants, Irenaeus (Adversus Haereses) and Hippolytus (Philosophumena), are so strongly divergent that they seem to many quite irreconcilable. According to Hippolytus, Basilides was apparently a pantheistic evolutionist; and according to Irenaeus, a dualist and an emanationist. Historians such as Philip Shaff have the opinion that "Irenaeus described a form of Basilidianism which was not the original, but a later corruption of the system. On the other hand, Clement of Alexandria surely, and Hippolytus, in the fuller account of his Philosophumena, probably drew their knowledge of the system directly from Basilides' own work, the Exegetica, and hence represent the form of doctrine taught by Basilides himself".[2]

The fundamental theme of the Basilidian system is the question concerning the origin of evil and how to overcome it.[3] A cosmographical feature common to many forms of Gnosticism is the idea that the Logos Spermatikos is scattered into the sensible cosmos, where it is the duty of the Gnostics, by whatever means, to recollect these scattered seed-members of the Logos and return them to their proper places[4] (cf. the Gospel of Eve). "Their whole system," says Clement, "is a confusion of the Panspermia (All-seed) with the Phylokrinesis (Difference-in-kind) and the return of things thus confused to their own places."

Creation

According to Hippolytus, Basilides asserted the beginning of all things to have been pure nothing. He uses every device of language to express absolute nonentity.[5] Nothing then being in existence, "not-being God" willed to make a not-being world out of not-being things. This not-being world was only "a single seed containing within itself all the seed-mass of the world," as the mustard seed contains the branches and leaves of the tree.[6] Within this seed-mass were three parts, or sonships, and were consubstantial with the not-being God. This was the one origin of all future growths; these future growths did not use pre-existing matter, but rather these future growths came into being out of nothing by the voice of the not-being God.

First sonship

Part subtle of substance. The first part of the seed-mass burst through and ascended to the not-being God.

Second sonship

Part coarse of substance. The second part of the seed-mass to burst forth could not mount up of itself, but it took to itself as a wing of the Holy Spirit, each bearing up the other with mutual benefit. But when it came near the place of the first part of the seed-mass and the not-being God, it could take the Holy Spirit no further, it not being consubstantial with the Holy Spirit. There the Holy Spirit remained, as a firmament dividing things above the world from the world itself below.[7]

Third sonship and the Great Archon

Part needing purification. From the third part of the seed-mass burst forth into being the Great Archon, "the head of the world, a beauty and greatness and power that cannot be uttered." He too ascended until he reached the firmament which he supposed to be the upward end of all things. There he "made to himself and begat out of the things below a son far better and wiser than himself". Then he became wiser and every way better than all other cosmical things except the seed-mass left below. Smitten with wonder at his son's beauty, he set him at his right hand. "This is what they call the Ogdoad, where the Great Archon is sitting." Then all the heavenly or ethereal creation, as far down as the moon, was made by the Great Archon, inspired by his wiser son.[8]

Another Archon arose out of the seed-mass, inferior to the first Archon, but superior to all else below except the seed-mass; and he likewise made to himself a son wiser than himself, and became the creator and governor of the aerial world. This region is called the Hebdomad. On the other hand, all these events occurred according to the plan of the not-being God.[9]

Gospel

The Basilidians believed in a very different gospel than orthodox Christians. Hippolytus summed up the Basilidians' gospel by saying: "According to them the Gospel is the knowledge of things above the world, which knowledge the Great Archon understood not: when then it was shewn to him that there exists the Holy Spirit, and the [three parts of the seed-mass] and a God Who is the author of all these things, even the not-being One, he rejoiced at what was told him, and was exceeding glad: this is according to them the Gospel."

That is, the Basilidians believed from Adam until Moses the Great Archon supposed himself to be God alone, and to have nothing above him. But it was thought to enlighten the Great Archon that there were beings above him, so through the Holy Spirit the Gospel was conveyed to the Great Archon.[10] First, the son of the Great Archon received the Gospel, and he in turn instructed the Great Archon himself, by whose side he was sitting. Then the Great Archon learned that he was not God of the universe, but had above him yet higher beings; and confessed his sin in having magnified himself.[11] From him the Gospel had next to pass to the Archon of the Hebdomad. The son of the Great Archon delivered the Gospel to the son of the Archon of the Hebdomad. The son of the Archon of the Hebdomad became enlightened, and declared the Gospel to the Archon of the Hebdomad, and he too feared and confessed.[12]

It remained only that the world should be enlightened. The light came down from the Archon of the Hebdomad upon Jesus both at the Annunciation and at the Baptism so that He "was enlightened, being kindled in union with the light that shone on Him". Therefore, by following Jesus, the world is purified and becomes most subtle, so that it can ascend by itself.[12] When every part of the sonship has arrived above the Limitary Spirit, "then the creation shall find mercy, for till now it groans and is tormented and awaits the revelation of the sons of God, that all the men of the sonship may ascend from hence".[13] When this has come to pass, God will bring upon the whole world the Great Ignorance, that everything may like being the way it is, and that nothing may desire anything contrary to its nature. "And in this wise shall be the Restoration, all things according to nature having been founded in the seed of the universe in the beginning, and being restored at their due seasons."[14]

Ethics

According to Clement of Alexandria, the Basilidians taught faith was a natural gift of understanding bestowed upon the soul before its union with the body and which some possessed and others did not. This gift is a latent force which only manifests its energy through the coming of the Saviour.

Sin was not the results of the abuse of free will, but merely the outcome of an inborn evil principle. All suffering is punishment for sin; even when a child suffers, this is the punishment of the inborn evil principle. The persecutions Christians underwent had therefore as sole object the punishment of their sin. All human nature was thus vitiated by the sinful; when hard pressed Basilides would call even Christ a sinful man,[18] for God alone was righteous. Clement accuses Basilides of a deification of the Devil, and regards as his two dogmas that of the Devil and that of the transmigration of souls.[19]

Cosmogony of Irenaeus and Epiphanius

In briefly sketching this version of Basilidianism, which most likely rests on later or corrupt accounts, our authorities are fundamentally two, Irenaeus and the lost early treatise of Hippolytus; both having much in common, and both being interwoven together in the report of Epiphanius. The other relics of the Hippolytean Compendium are the accounts of Philaster (32), and the supplement to Tertullian (4).

Creation

At the head of this theology stood the Unbegotten, the Only Father. From Him was born or put forth Nûs, and from Nûs Logos, from Logos Phronesis, from Phronesis Sophia and Dynamis, from Sophia and Dynamis principalities, powers, and angels. This first set of angels first made the first heaven, and then gave birth to a second set of angels who made a second heaven, and so on till 365 heavens had been made by 365 generations of angels, each heaven being apparently ruled by an Archon to whom a name was given, and these names being used in magic arts. The angels of the lowest or visible heaven made the earth and man. They were the authors of the prophecies; and the Law in particular was given by their Archon, the God of the Jews. He being more petulant and wilful than the other angels (ἰταμώτερον καὶ αὐθαδέστερον), in his desire to secure empire for his people, provoked the rebellion of the other angels and their respective peoples.

Christ

Then the Unbegotten and Innominable Father, seeing what discord prevailed among men and among angels, and how the Jews were perishing, sent His Firstborn Nûs, Who is Christ, to deliver those Who believed on Him from the power of the makers of the world. "He," the Basilidians said, "is our salvation, even He Who came and revealed to us alone this truth." He accordingly appeared on earth and performed mighty works; but His appearance was only in outward show, and He did not really take flesh. It was Simon of Cyrene that was crucified; for Jesus exchanged forms with him on the way, and then, standing unseen opposite in Simon's form, mocked those who did the deed (this is starkly contradicted by Hippolytus' view of the Basilidians).[20][21] But He Himself ascended into heaven, passing through all the powers, till He was restored to the presence of His own Father.

Abrasax

The two fullest accounts, those of Irenaeus and Epiphanius, add by way of appendix another particular of the antecedent mythology; a short notice on the same subject being likewise inserted parenthetically by Hippolytus.[22] The supreme power and source of being above all principalities and powers and angels (such is evidently the reference of Epiphanius's αὐτῶν: Irenaeus substitutes "heavens," which in this connexion comes to much the same thing) is Abrasax, the Greek letters of whose name added together as numerals make up 365, the number of the heavens; whence, they apparently said, the year has 365 days, and the human body 365 members. This supreme Power they called "the Cause" and "the First Archetype," while they treated as a last or weakest product this present world as the work of the last Archon.[23] It is evident from these particulars that Abrasax was the name of the first of the 365 Archons, and accordingly stood below Sophia and Dynamis and their progenitors; but his position is not expressly stated, so that the writer of the supplement to Tertullian had some excuse for confusing him with "the Supreme God."

Precepts

On these doctrines, various precepts are said by the Basilidians' opponents to have been founded.

Antinomianism

When Philaster (doubtless after Hippolytus) tells us in his first sentence about Basilides that "he violated the laws of Christian truth by making an outward show and discourse concerning the Law and the Prophets and the Apostles, but believing otherwise," the reference is probably revealing an antinomian sentiment among the Basilidians. The Basilidians considered themselves to be no longer Jews, and to have become more than Christians. Repudiation of martyrdom was naturally accompanied by indiscriminate use of things offered to idols. And from there the principle of indifference is said to have been carried so far as to sanction promiscuous immorality.

Magic

Among the later followers of Basilides, magic, invocations, "and all other curious arts" played a part. The names of the rulers of the several heavens were handed down as a weighty secret, which was a result of the belief that whoever knew the names of these rulers would after death pass through all the heavens to the supreme God. In accordance with this, Christ also, in the opinion of these followers of Basilides, was in the possession of a mystic name (Caulacau) by the power of which he had descended through all the heavens to Earth, and had then again ascended to the Father. Redemption, accordingly, could be conceived as the revelation of mystic names. Whether Basilides himself had already given this magic tendency to Gnosticism cannot be decided.

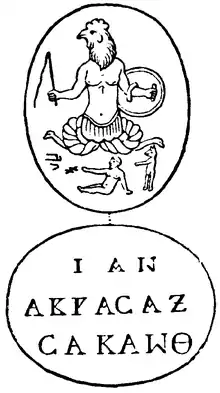

A reading taken from the inferior MSS. of Irenaeus has added the further statement that they used "images"; and this single word is often cited in corroboration of the popular belief that the numerous ancient gems on which grotesque mythological combinations are accompanied by the mystic name ΑΒΡΑΣΑΞ were of Basilidian origin.

It has been shown[24] that there is little tangible evidence for attributing any known gems to Basilidianism or any other form of Gnosticism, and that in all probability the Basilidians and the pagan engravers of gems alike borrowed the name from some Semitic mythology. No attempts of critics to trace correspondences between the mythological personages, and to explain them by supposed condensations or mutilations, have attained even plausibility.

Martyrdom

The most distinctive is the discouragement of martyrdom, which was made to rest on several grounds. To confess the Crucified was called a token of being still in bondage to the angels who made the body, and it was condemned especially as a vain honour paid not to Christ, who neither suffered nor was crucified, but to Simon of Cyrene.

The contempt for martyrdom, which was perhaps the most notorious characteristic of the Basilidians, would find a ready excuse in their master's speculative paradox about martyrs, even if he did not discourage martyrdom himself.

Relationship to Judaism

According to both Hippolytus and Irenaeus, the Basilidians denied that the God of the Jews was the supreme God. According to Hippolytus, the God of the Jews was the Archon of the Hebdomad, which was inferior to the Great Archon, the Holy Spirit, the seed-mass (threefold sonship), and the not-being God.

According to Irenaeus, the Basilidians believed the God of the Jews was inferior to the 365 sets of Archons above him, as well as the powers, principalities, Dynamis and Sophia, Phronesis, Logos, Nûs, and finally the Unbegotten Father.

Resurrection of the body

Basilidians expected the resurrection of the soul alone, insisting on the natural corruptibility of the body.

Secrecy

Their discouragement of martyrdom was one of the secrets which the Basilidians diligently cultivated, following naturally on the supposed possession of a hidden knowledge. Likewise, their other mysteries were to be carefully guarded, and disclosed to "only one out of 1000 and two out of 10,000."

The silence of five years which Basilides imposed on novices might easily degenerate into the perilous dissimulation of a secret sect, while their exclusiveness would be nourished by his doctrine of the Election; and the same doctrine might further after a while receive an antinomian interpretation.

Later Basilidianism

Irenaeus and Epiphanius reproach Basilides with the immorality of his system, and Jerome calls Basilides a master and teacher of debaucheries. It is likely, however, that Basilides was personally free from immorality and that this accusation was true neither of the master nor of some of his followers. However, imperfect and distorted as the picture may be, such was doubtless in substance the creed of Basilidians not half a century after Basilides had written. In this and other respects our accounts may possibly contain exaggerations; but Clement's complaint of the flagrant degeneracy in his time from the high standard set up by Basilides himself is unsuspicious evidence, and a libertine code of ethics would find an easy justification in such maxims as are imputed to the Basilidians.

Two misunderstandings have been specially misleading. Abrasax, the chief or Archon of the first set of angels, has been confounded with "the Unbegotten Father," and the God of the Jews, the Archon of the lowest heaven, has been assumed to be the only Archon recognized by the later Basilidians, though Epiphanius[25] distinctly implies that each of the 365 heavens had its Archon. The mere name "Archon" is common to most forms of Gnosticism. Basilidianism seems to have stood alone in appropriating Abrasax; but Caulacau plays a part in more than one system, and the functions of the angels recur in various forms of Gnosticism, and especially in that derived from Saturnilus. Saturnilus likewise affords a parallel in the character assigned to the God of the Jews as an angel, and partly in the reason assigned for the Saviour's mission; while the Antitactae of Clement recall the resistance to the God of the Jews inculcated by the Basilidians.

Other "Basilidian" features appear in the Pistis Sophia, viz. many barbaric names of angels (with 365 Archons, p. 364), and elaborate collocations of heavens, and a numerical image taken from Deuteronomy 32:30 (p. 354). The Basilidian Simon of Cyrene apparently appears in the Second Treatise of the Great Seth, where Jesus says: "it was another, Simon, who bore the cross on his shoulder. It was another upon whom they placed the crown of thorns ... And I was laughing at their ignorance."

History

There is no evidence that the sect extended itself beyond Egypt; but there it survived for a long time. Epiphanius (about 375) mentions the Prosopite, Athribite, Saite, and "Alexandriopolite" (read Andropolite) nomes or cantons, and also Alexandria itself, as the places in which it still throve in his time, and which he accordingly inferred to have been visited by Basilides.[26] All these places lie on the western side of the Delta, between Memphis and the sea. Nearer the end of the 4th century, Jerome often refers to Basilides in connexion with the hybrid Priscillianism of Spain, and the mystic names in which its votaries delighted. According to Sulpicius Severus[27] this heresy took its rise in "the East and Egypt"; but, he adds, it is not easy to say "what the beginnings were out of which it there grew" (quibus ibi initiis coaluerit). He states, however, that it was first brought to Spain by Marcus, a native of Memphis. This fact explains how the name of Basilides and some dregs of his disciples' doctrines or practices found their way to so distant a land as Spain, and at the same time illustrates the probable hybrid origin of the secondary Basilidianism itself.

Texts

Basilidian works are named for the founder of their school, Basilides (132–? AD). These works are mainly known to us through the criticisms of one of his opponents, Irenaeus in his work Adversus Haereses. The other pieces are known through the work of Clement of Alexandria:

- The Octet of Subsistent Entities (Fragment A)

- The Uniqueness of the World (Fragment B)

- Election Naturally Entails Faith and Virtue (Fragment C)

- The State of Virtue (Fragment D)

- The Elect Transcend the World (Fragment E)

- Reincarnation (Fragment F)

- Human Suffering and the Goodness of Providence (Fragment G)

- Forgivable Sins (Fragment H)

Footnotes

- Clement, Stromata. i. 21 § 18

- Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Second Series page 178, note 7.

- Epiphanius, Haer. xxiv. 6

- Pulver, Max (1955). "Jesus' Round Dance and Crucifixion". In Campbell, Joseph (ed.). The Mysteries: Papers from the Eranos Yearbooks. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 177. ISBN 0-691-01823-5.

But in Gnosticism ... the suffering of the Redeemer implies not his real death, but his descent into the hyle (matter) and the gathering of the spermata in the hyle.

- Hippolytus, Philosophumena vii. 20.

- Hippolytus, Philosophumena vii. 21.

- Hippolytus, Philosophumena vii. 22.

- Hippolytus, Philosophumena vii. 23.

- Hippolytus, Philosophumena vii. 24.

- Hippolytus, Philosophumena vii. 25.

- Wisdom to "separate and discern and perfect and restore," Clem. Strom. ii. 448 f.

- Hippolytus, Philosophumena vii. 26.

- Hippolytus, Philosophumena vii. 27.

- προλελογισμένος: cf. c. 24, s. f.; x. 14.

- Hippolytus, "After the Nativity already made known, all incidents concerning the Saviour came to pass according to them [the Basilidians] as they are described in the Gospels."

- Hippolytus, "It was necessary that the things confused should be sorted by the division of Jesus. That therefore suffered which was His bodily part, which was of the [world], and it was restored into the [world]; and that rose up which was His psychical part... and it was restored into the Hebdomad; and he raised up that which belonged to the summit where sits the Great Archon, and it abode beside the Great Archon: and He bore up on high that which was of the [Holy] Spirit, and it abode in the [Holy] Spirit; and the third [part of the seed-mass], which had been left behind in [the heap] to give and receive benefits, through Him was purified and mounted up to the [first part of the seed-mass], passing through them all."

- Hippolytus, "Thus Jesus is become the first fruits of the sorting; and the Passion has come to pass for no other purpose than this, that the things confused might be sorted."

- Clemens, Strom. iv. 12 § 83, &c.

- Clemens, Strom. iv. 12 § 85: cf. v. ii § 75

- M Mohar Ali, Quran and the Orientalists, pg 68

- Ehrman, Bart (2005). Lost Christianities. OUP. p. 188. ISBN 0195182499

- Hippolytus, Philosophumena vii. 26, p. 240: cf. Uhlhorn, D. Basilid. Syst. 65 f.

- Epiph. 74 A.

- D. C. B. (4-vol. ed.), art. Abrasax, where Lardner (Hist. of Heretics, ii. 14-28) should have been named with Beausobre.

- Epiphanius 69 B, C.

- Epiphanius, Panarion 68 C.

- Sulpicius Severus, Chron. ii. 46.

References

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Wace, Henry; Piercy, William C., eds. (1911). "Basilides, Gnostic sect founder". Dictionary of Christian Biography and Literature to the End of the Sixth Century (3rd ed.). London: John Murray.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Wace, Henry; Piercy, William C., eds. (1911). "Basilides, Gnostic sect founder". Dictionary of Christian Biography and Literature to the End of the Sixth Century (3rd ed.). London: John Murray.- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Bousset, Wilhelm (1911). "Basilides". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 478–479.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Basilides (1)". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Basilides (1)". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Krüger, G. (1914). "Basilides and the Basilidians". In Jackson, Samuel Macauley (ed.). New Schaff–Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge (third ed.). London and New York: Funk and Wagnalls.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Krüger, G. (1914). "Basilides and the Basilidians". In Jackson, Samuel Macauley (ed.). New Schaff–Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge (third ed.). London and New York: Funk and Wagnalls.{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)