Bates family

The Bates family is an American political and banking family from Maine and Massachusetts whose members include a prominent member of the prestigious Hell Fire Club, the 26th U.S. Attorney General serving under Abraham Lincoln, the second Governor of Missouri, a member of the U.S. House of Representatives for Arkansas, and a prominent textile tycoon who founded the Bates Manufacturing Company and Bates College in Lewiston, Maine. The family includes various merchants, politicians, inventors, clergymen, artists, and socialites.

| Bates | |

|---|---|

| |

| Current region | New England |

| Place of origin | Lydd, Kent County, England[1] |

| Connected families | Alden Family Gilbert Family |

| Estate(s) | The Campus of Bates College Frye Street Historic District |

The family is related to the prominent political Gilbert family and indirectly to the Alden family, the first family on the Mayflower.

History

Early prominence

The Bates family most likely originated from Lydd in Kent, England.[1] They have lived there since at least the 13th Century. The prominence of the Bates family began with its patriarch, Benjamin Bates I (1651–1710), who worked his way into the legal world as a young boy, in Edinburgh, Scotland,[2] and soon gained a reputation for winning arguments and debates among the most senior councilmen in his town. His rapid ascension through the ranks of the law landed him high paying commissions and high-profile cases, eventually leading him into banking. Little is written about the first Benjamin Bates, and he is most noted for being survived by Benjamin Bates II, is often noted as the "revival patriarch"[3] as his life and pursuits landed him in the elite Hellfire Club hosted by Francis Dashwood. Using the considerable sum bestowed upon to him by his father he lived a life of pure excess and began collecting art to soothe his restlessness.[3] Benjamin Bates III, went on to become a prominent merchant of food and working tools. The family can trace their ancestors to John Alden who was crew member on the historic 1620 voyage of the Pilgrim ship Mayflower, through the union of Elkanah Bates (1779 - 1841) and Hannah Copeland.[4] The family assumed their family crest upon their marriage.[5][6] Alden's daughter Ruth married John Bass, and were survived by Benjamin, Williams and eventually Hannah Copeland, who began the lineage with the Bates family.[7] The Bates family starts in England but moved to and from Massachusetts periodically, with certain members being born abroad and others being born in New England. Deeply religious the family founded numerous (some now defunct) religious institutions and centers.[8] Alfred Bates fought in the American Revolution as a captain, and later became a brigadier general for the Massachusetts State Militia.[9][10]

Edward Bates born in Goochland County, Virginia, on the Bates' Belmont plantation, he was privately tutored at home as a boy. When older, he attended Charlotte Hall Military Academy in Maryland. Bates's first foray into politics came in 1820, with election as a member of the state's constitutional convention. He wrote the preamble to the state constitution—an honor that later influenced his fight against the radical Missouri Constitution of 1865. He next was appointed as the new state's Attorney General. He became a prominent member of the Whig Party during the 1840s, where his political philosophy closely resembled that of Henry Clay. While a slaveholder, during this time, Bates became interested in the case of the slave Polly Berry, who in 1843 gained her freedom decades after having been held illegally in the free state of Illinois for several months. In 1850, President Millard Fillmore asked Bates to serve as U.S. Secretary of War, but he declined. At the Whig National Convention in 1852, Bates was considered for nomination as vice-president on the party ticket, and he led on the first ballot before losing on the second ballot to William Alexander Graham. His brothers Frederick and James Woodson also served in politics as Governor of Missouri, and Senator respectively.[11]

Familial expansion

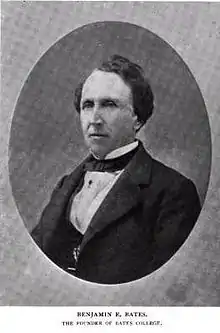

Many descendants of the first Bates members lived modestly off of their inheritances until Elkanah Bates began heavily investing all over the state of Massachusetts serving some clients in Maine, and starting his own cotton factory. His wealth was increased considerably, from cotton brought up from the slave plantations of Alabama, and Mississippi.[10] Elkanah Bates was survived by Benjamin Edward Bates IV, who went on to be one of the most prominent businessmen in the United States and the wealthiest man in Maine for nearly half a century. Benjamin Bates IV was born in Mansfield, Massachusetts on July 12, 1808, to Hannah Copeland and Elkanah Bates as their third child out of eight. The family has historical ties to the Congregational Church, and both of his parents belonged to the local church in Mansfield. He was privately schooled the Wrentham Academy, at 15 and moved to Boston in 1829, at age 21.[12] He soon followed the footsteps of his father and began his early business career. He co-founded the firm of Davis, & Bates in Boston, and his wealth exponentially increased so much so that his overall business engagements quelled the Manhattan panic of 1837's effects in Maine. His principle accomplishment during his early business career was the establishment of Bates Manufacturing Company. The company went on to be the largest manufacturing company in the state of Maine and provided two-thirds of all textile output for the state.[13] It employed approximately five thousand people from Canadian and Irish descent.

He moved to Lewiston, Maine, which was considered a pivotal moment in his life as "the third reincarnation of the Bates man".[11] He went on to found the Lewiston Water Company, and the Bates Mill which was the largest Mill in the city. Bates' practices with the mill dominated the mill industry and was one of the first great U.S. business trusts. He initially gained wealth and influence from manufacturing textiles and estate development with correspondence to the mills. His mills extended from the Androscoggin River to northern Lewiston.[14] Under Bates’ supervision, during the Civil War, the mill produced textiles to the Union Army. His mills generated employment for thousands of Canadians, and immigrants from Europe. The mill was Maine's largest employer for three decade. Bates bought an unprecedented amount of cotton prior to the outbreak of the Civil War. During the War, Bates was able to produce uniforms for the Union Army as well as other textiles. His efforts concluded numerous periodic shortages of textiles through the war to be quelled, he was dubbed, the "supplier of movement."[15] His capitalization of this, saw to great levels of profit for his firms and companies, and caused dozens of mills to be closed due to overwhelming competition.[9] His business pursuits stemmed into the railroad industry, and he went on to control 15% of all railroads in Maine.[16] Bates was drawn to the newly conceptualized Maine State Seminary in central Lewiston, and asked its founder and one of his good friends Oren Burbank Cheney to be involved, which would become his crowning achievement.[17][18]

Bates College

After being approached by Oren Burbank Cheney, he began offering up the services of his mills, canals, and other holdings in the construction of such an institution. In 1852, he personally pledged another $6,000 to the school. In 1853, Oren Burbank Cheney appointed him as a Trustee of the college and in 1854 subsequently became chairman of the Board of Trustees of the college due to his considerable donations.[19] He went on to donate $25,000 for the foundation of agriculture department and moved a subscription of $75,000 for campus expansion. On February 21, 1873, he donated $100,000 on the condition that the amount was met by third-party donors, within five years. Although he placed conditions on his donations, he realized his donations regardless of the conditions being met.[20]

By his death in 1878, Bates' donations to the college totalled over $100,000, and overall contributions valued at $250,000.[20] Cheney renamed the college after Bates without his knowledge.[21]

Bates wrote to Cheney and noted the naming of the college after him on May 18, 1863, saying:

In regard to the name of your college, I can only say that my choice would have been to name it after someone more worthy of its inception and history... I am sorry the Board of Trustees have renamed the college after me as I cannot raise so much money as people may think I am asking money for myself.[20]

By his death in 1878, Bates had amassed a total net worth of approximately $79.4 million (worth $1.7 billion in 2016), and as the richest member of the family. The family possessed assets that included his holdings in Maine, New York, and Massachusetts that encompassed the non-operational value of B. T. Loring & Co., Bates, Turner & Co., his holding company the Bates Manufacturing Company, his stake in the Lewiston Water Company, Bates Mill, and miscellaneous banking endeavors in New York. In his Will he pledged $50,000 to his wife Sarah Gilbert along with his 2.8 million dollar estate, $10,000 to his brother William, $10,000 to his brother Elkanah Bates II, $10,000 equally divided among the children of his sister, Charlotte, $10,000 to Edward Atkinson, and $10,000 to George Fabian. He left each of his children, Benjamin Edward V, Lilian, Sarah, and Author $250,000 in the form of a trust.[22]

However, Bates had $200,000 in outstanding debt and a pledged $100,000 to Bates College after his death. His family was required expend the $100,000 pledged but due to conditions placed on the inheritances, restricted distribution, and familial debt, the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts eventually ruled that Bates' heirs did not have to pay Bates College the pledged $100,000. After a period of recession the college began to financially recuperate to a larger endowment, independently. Over the next couple of years Bates College's endowment grew slowly and steadily.

Although much has been speculated on the calculated sum of the family's wealth, many agree it has fallen below Bates' $79.4 million in 1878.[23]

Members

Benjamin Bates I (c.1651 – aft. 1716)[24] m. Esther Bates (c. 1651 – aft. March 24, 1716)[25]

- Benjamin Bates II (c.1716–1790) m. Mary Dolbier (1726–1796)

- Thomas Bates (1741–1805) m. Caroline Woodson (1751–1771)

- Frederick Bates (1777–1825) m. Nacy Opie Ball (1802–1877)[26]

- Emily Caroline Bates (1820–1891)[26]

- Lucius Lee Bates (1821–1898)[26]

- Woodville Bates (1823–1840)[26]

- Frederick Jr. Bates (1826–1862)[26]

- James Woodson Bates (1788–1846) m. Elizabeth Moore (1810 – .d)

- Edward Bates (1793–1869) m. Julia Coalter (1807–1880) (The couple had 17 children)[27]

- Benjamin Bates III (1749–1818) m. Abigail Billings (1656–1716)

- Billing Bates (1770–1850; unmarried)

- Betsey Cobb (1771 – 1843) m. Jonathan Cobb (1764–1853)[28]

- Sally Day (1773–1851) m. Samuel Day (1759–1812)

- Eunice Knap (1775 – .d) m. John Knap Jr. (1745 – .d)

- Polly Pratt (1782 – .d) m. Solomon Pratt (1763 – .d)

- Alfred Bates (1784–1786)

- Charlotte Skinner (1787 – .d) m. Solomon Skinner (1790 – .d)

- Harriet Clap (1789 – .d) m. Warren Clap (1759 – .d)

- Elkanah Bates (1779–1841) m. Hannah Copeland (1780–1834)

- Gerry Bates (1800–1878)

- Frederick Bates (1857-1920)

- Alben Bates (1886-1980)

- Henry Glos Bates (1923-2018)

- Christine Crum

- Anne Crum Ross

- Henry Crum

- Patricia Pace

- Gregory Pace Jr.

- John Henry Pace

- Becky Dickinson

- Robert Dickinson

- Benjamin Dickinson

- Bradley Dickinson

- Sunny Bates

- Lola Bates Campbell

- Lucy Bates Campbell

- Christine Crum

- Henry Glos Bates (1923-2018)

- Alben Bates (1886-1980)

- Frederick Bates (1857-1920)

- Loretta Bates (1804 – .d; unmarried)

- Stella Bates (1806 – .d; unmarried)

- Benjamin Bates IV (1808–1878) m. Sarah Chapman Gilbert (2nd wife and daughter of Joseph Gilbert) (1832–1882)

- Josephine Bates II (with 1st wife Josephine Louisa Shepard (1815–1842)) (1839–1886)

- Benjamin Edward Bates V (1863–1906)

- Sarah Hersher Bates (1867–1937)

- Lillian Gilbert Bates (1872–1951)

- Arthur Hobart Herscher Bates (1870–1953)

- William Billings Bates (1811–1880) m. Mary Willard (1815–1877)

- Alfred Willard Bates (1836–1892)

- John Grenville Bates (1880–1944)

- Harriet Richmond Bates (1843–1847)

- William Ellery Bates (1855–1857)

- Alfred Willard Bates (1836–1892)

- Charlotte Bates (1813 – .d; unmarried)

- Elkanah Gerry Bates (1816 – 1881; unmarried)

- Alfred Bates (1819 – .d; unmarried)

- Elizabeth Bates (1823 – .d; unmarried)

- Gerry Bates (1800–1878)

- Thomas Bates (1741–1805) m. Caroline Woodson (1751–1771)

Note: Many of the family members are buried at the Bates Family Memorial at 930 Fir Avenue. With Benjamin Edward Bates IV's first wife, Josephine Louisa Shepard, there is speculation on the possibility of a child between the two, named Josephine Bates. Benjamin Edward Bates IV's second wife, Sarah Chapman Gilbert, was over 20 years younger than he was.

References

Further reading

- Boston Herald, The People You Know - Benjamin Edward Bates. Boston Herald Publishing, 2010

- Harry Chase, Bates College was named for Mansfield Man. Edmund Muskie Archives, Bates College, Lewiston, Maine: Bates College.

- Johnnett, R. F. (1878). Bates Student: A Monthly Magazine. Edmund Muskie Archives, Bates College, Lewiston, Maine: Bates College.

- Gilbert T. Joseph, Reminiscences of Early Days. Edmund Muskie Archives, Bates College, Lewiston, Maine: Bates College.

- Thomas Mercer (1990) Bates: A Familial Journey. Boston Her. Press.

Citations

- Firmin, Lois. Ancestors and Descendants of George and Margarte Bates MARTIN.

- Mercer pp.16

- Mercer pp. 17

- Society of Colonial Dames, 1897; Section 75.

- Mercer, pp. 13

- Mercer, pp. 19 (apps. 2)

- Mercer 12-15

- Mercer pp. 20

- Chase, Harry. Bates College was named after Mansfield Man. Edmund Muskie Archives: National Resources Trust of Mansfield. p. 5.

- Mercer pp. 22

- Mercer, pp. 25

- Johnnett, R. F. (1878). Bates Student: A Monthly Magazine. Edmund Muskie Archives, Bates College, Lewiston, Maine: Bates College. pp. Multi–source, pp. 143.

- Johnnett, R. F. (1878). Bates Student: A Monthly Magazine. Edmund Muskie Archives, Bates College, Lewiston, Maine: Bates College. pp. Multi–source, pp. 150.

- Johnnett, R. F. (1878). Bates Student: A Monthly Magazine. Edmund Muskie Archives, Bates College, Lewiston, Maine: Bates College. pp. Multi–source, pp. 164.

- Johnnett, R. F. (1878). Bates Student: A Monthly Magazine. Edmund Muskie Archives, Bates College, Lewiston, Maine: Bates College. pp. Multi–source, pp. 173.

- Mercer pp. 27

- Mercer, pp. 30

- Johnnett, R. F. (1878). Bates Student: A Monthly Magazine. Edmund Muskie Archives, Bates College, Lewiston, Maine: Bates College. pp. Multi–source, pp. 13.

- "Chapter 1 | 150 Years | Bates College". www.bates.edu. 22 March 2010. Retrieved 2015-12-13.

- Johnnett, R. F. (1878). Bates Student: A Monthly Magazine. Edmund Muskie Archives, Bates College, Lewiston, Maine: Bates College. pp. Multi–source, pp. 2.

- Mercer, pp. 31

- Unknown, Publisher (1879). "The Will of Benjamin Edward Bates". Boston Herald.

- Mercer, pp. 33

- There is some speculation on the actual date of birth of the patriarch of the Bates family, with many agreeing on the

- Mercer, Thomas (1990). Bates: A Familial Journey. Boston Her. Press. pp. 12–57.

- William Smith Bryan; Macgunnigle (1 June 2009). Rhode Island Freemen, 1747-1755. Genealogical Publishing Com. pp. 131–. ISBN 978-0-8063-0753-4.

- "Cabinet and Vice President: Edward Bates" Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine, Mr. Lincoln's White House, The Lincoln Institute, 1999–2011, accessed 4 January 2011

- "Jonathan Cobb". Early Vital Records of Massachusetts. Retrieved 2020-09-15.