Todt Battery

The Todt Battery, also known as Batterie Todt, was a battery of coastal artillery built by Nazi Germany during World War II, located in the hamlet of Haringzelles, Audinghen, near Cape Gris-Nez, Pas de Calais, France.

| Todt Battery | |

|---|---|

| Part of Atlantic Wall | |

| Haringzelle, Audinghen, Pas de Calais, France | |

A British soldier poses next to the recently captured German 380 mm gun Todt Battery at Cap Gris-Nez. | |

.svg.png.webp) .svg.png.webp) Kriegsmarine Ensign | |

| Coordinates | 50.8443°N 1.5999°E |

| Type | Coastal battery |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Private |

| Open to the public | One casemate is open to the public |

| Condition | Four casemates, in varied condition |

| Site history | |

| Built | 22 July 1940 – 20 January 1942 |

| Built by | Organisation Todt |

| In use | 1942–44 |

| Materials | Concrete and steel |

| Battles/wars | Operation Sea Lion, Channel Dash, Hellfire Corner, Operation Undergo |

| Garrison information | |

| Garrison | |

The battery consisted of four Krupp 380-millimetre (15 in) guns with a range up to 55.7 kilometres (34.6 mi),[1] capable of reaching the British coast, each protected by a bunker of reinforced concrete. Originally to be called Siegfried Battery, it was renamed in honor of the German engineer Fritz Todt, creator of the Todt Organisation. It was later integrated into the Atlantic Wall.

The 3rd Canadian Infantry Division attacked the Cape Gris-Nez batteries on 29 September 1944, and the positions were secured by the afternoon of the same day. The Todt battery fired for the last time on 29 September 1944 and was taken hours later by the North Nova Scotia Highlanders that landed in Normandy, as part of the 9th Infantry Brigade, 3rd Canadian Infantry Division, after an intense aerial bombardment, as part of Operation Undergo.

History

Germany's swift and successful occupation of France and the Low Countries gained control of the Channel coast. Grand Admiral Erich Raeder met Hitler on 21 May 1940 and raised the topic of invasion, but warned of the risks and expressed a preference for blockade by air, submarines and raiders.[2][3] By the end of May, the Kriegsmarine had become even more opposed to invading Britain following its costly victory in Norway. Over half of the Kriegsmarine surface fleet had been either sunk or badly damaged in Operation Weserübung, and his service was hopelessly outnumbered by the ships of the Royal Navy.[4][5]

In an OKW directive on 10 July, General Wilhelm Keitel requested artillery protection during the planned invasion:

In pursuance of the requested analysis of artillery protection for transports to Britain (...), the Führer has ordered: All preparations are to be made to provide strong frontal and flank artillery protection for the transportation and landing of troops in case of a possible crossing from the coastal strip Calais-Cape Gris-Nez – Boulogne. All suitable available heavy batteries are to be employed for this purpose by the Army High Command and the Naval High Command under the direction of the Naval High Command and are to be installed in fixed positions in conjunction with the Todt Organization.

— Keitel, [6]

OKW Chief of Staff Alfred Jodl set out the OKW proposals for the proposed invasion of Britain in a memorandum issued on 12 July, which described it as "a river crossing on a broad front", irritating the Kriegsmarine.

On 16 July 1940 Hitler issued Führer Directive No. 16, setting in motion preparations for a landing in Britain, codenamed Operation Sea Lion.[7] One of the four conditions for the invasion to occur set out in Hitler's directive was the coastal zone between occupied France and England must be dominated by heavy coastal artillery to close the Strait of Dover to Royal Navy warships and merchant convoys.[8] The Kriegsmarine's Naval Operations Office deemed this a plausible and desirable goal, especially given the relatively short distance, 34 km (21 mi), between the French and English coasts. Orders were therefore issued to assemble and begin emplacing every Army and Navy heavy artillery piece available along the French coast, primarily at Pas-de-Calais. This work was assigned to the Organisation Todt and commenced on 22 July 1940.[9][10]

By early August 1940, all of the Army's large-caliber railway guns were operational taking advantage of the narrow width of the English Channel in the Pas-de-Calais. Firing sites for these railway guns were quickly set up between Wimereux, in the south, and Calais in the north, along the axis Calais-Boulogne-sur-Mer making the most of the railway tracks entering the dunes and skirting the hills of Boulonnais, before fanning out behind Cape gris-Nez. Other firing locations were set up behind Wissant and near Calais, at the level of the Digue Royale (royal dyke). Copied from swing bridges and railway turntables, Vögele rotating tables were assembled, on stabilized or lightly reinforced ground, at the end of these various deviations enabling rapid adjustments and all-round firing of these railway guns. Outside of firing periods, the guns and their accompanying carriages would find refuge in quarries, under the railway tunnels or under one of the three dombunkers (cathedral-bunkers), reinforced concrete shelters of an ogival shape whose construction began in September 1940.[11][12] Six 28 cm K5 pieces and a single 21 cm (8.3 in) K12 gun, with a range of 115 km (71 mi), could only be used effectively against land targets. Thirteen 28 cm (11 in) and five 24 cm (9.4 in) pieces, plus additional motorized batteries comprising twelve 24 cm guns and ten 21 cm weapons. The railway guns could be fired at shipping but were of limited effectiveness due to their slow traverse speed, long loading time and ammunition types.[13]

Better suited for use against naval targets were the heavy naval batteries that began to be installed around the end of July 1940. First came the Siegfried Battery at Audinghen, south of Cape gris-Nez, (later increased to 4 and renamed Todt Battery). Four naval batteries were operational by mid-September 1940: Friedrich August with three 30.5 cm (12.0 in) barrels; Prinz Heinrich with two 28 cm guns; Oldenburg with two 24 cm weapons and, largest of all, Siegfried (later renamed Batterie Todt) with a pair of 38 cm (15 in) guns.[14]

While the bombing of Britain intensified during the Blitz, Hitler issued his Directive No. 21 on 18 December 1940 instructing the Wehrmacht to be ready for a quick attack to commence his long-planned invasion of the Soviet Union.[15][16] Operation Sea Lion lapsed, never to be resumed.[17] On 23 September 1941, Hitler ordered all Sea Lion preparations to cease. Most historians agree Sea Lion would have failed regardless, because of the weaknesses of German sea power, compared to the Royal Navy .[18]

On 23 March 1942, days after the British raid on the German coastal radar installation at Bruneval, Hitler issued Führer Directive No. 40, which called for the creation of an "Atlantic Wall", an extensive system of coastal defenses and fortifications, along the coast of continental Europe and Scandinavia as a defense against an anticipated Allied invasion of Nazi-occupied Europe from the United Kingdom.[19] The manning and operation of the Atlantic Wall was administratively overseen by the German Army, with some support from Luftwaffe ground forces. The fortification of the Atlantic coast, with a special attention to ports, was accelerated in the aftermath the British amphibious attack on the heavily defended Normandie dry dock at St Nazaire during Operation Chariot on 28 March 1942.[20] The Führer Directive No. 51 definitely confirmed the defensive role of the batteries of the Cape Gris-Nez on 3 November 1943.[21]

Description

Built on the small plateau of Haringzelles, located 3 km southeast of Cape gris-Nez, the Todt battery consisted of four casemates. Each casemate consisted of two parts: the firing chamber which housed the 38 cm SK C/34 naval guns under an armored turret, designated as Bettungsschiessgerüst C/39, and, on two floors, one of which was underground, the ammunition bunkers and all the facilities needed for the ammunition, the machinery and the crew.[22][23][24]

The casemates are 47 meters long, 29 wide and 20 high, 8 of which are underground.[23] The reinforced concrete walls and roof are 3.5 m thick to be able to resist 380 mm shells, ordinary 4000 pound bombs or 2000 pound armor-piercing bombs.[23]

The casemates were distributed along an arc of a circle with a radius of about 400 meters. In addition to the large-caliber guns, this battery also commanded the following weapon systems and buildings: 14 passive bunkers, four barracks, a belt of 15 "Tobruks" (small stand-alone bunkers, with a hole at the top, usually manned by two people that served as an observation post or machine gun nest), three bunkers with anti-tank guns facing south and directed towards the interior of the coast, nine pieces of anti-aircraft guns of French origin, installed at the center of the battery, a drinking water pumping station, a hospital bunker and a pre-existing farm, between casemate 2 and casemate 3, integrated into the defensive system to serve as barracks and an observation post.[22][23]

Each casemate had a buffer stock of propelling charges and shells but relied on two separated ammunition bunkers located near the hamlet of Onglevert, located 1.5 km (1 mi) east of the battery Todt. Each casemate was connected to these ammunition bunkers (30 x 20 x 5 m) by a truck road and by a network of Decauville-type narrow-gauge tracks. These two large constructions were made up of 6 cells arranged on either side of a corridor closed at each end by a heavy double-winged armored door.[25] They were integrated into the strongpoint Wn Onglevert, renamed Wn 183 Eber from 1944.[26]

The battery fired its first shell on 20 January 1942, although it was only officially opened in February 1942 in the presence of Admirals Karl Dönitz and Erich Raeder.[27][28] Originally to be called Siegfried Battery, it was renamed in honor of the German engineer Fritz Todt, creator of the Todt Organisation and responsible for the construction of the Atlantic Wall, who died on 8 February 1942 in a plane crash days before the battery's inauguration after meeting with Hitler at his Eastern Front military headquarters ("Wolf's Lair") near Rastenburg in East Prussia.[29][30] This decision was materialized by embossed 1.50-m high letters, displayed on Casemate 3. Hitler visited the Todt battery on 23 December 1940.[31][32]

In 1941, the battery was initially codenamed 18. When integrated into the Atlantic wall, the Todt Battery, its close-combat defensive positions and its anti-aircraft guns formed the strongpoint Stützpunkt (StP) 213 Saitenspiel in 1943, renamed StP 166 Saitenspiel in 1944.[22]

Construction

Before 1940, Haringzelles consisted of three farmsteads bordered by low walls and bushes. The occupants left shortly after the German engineers chose the site to build the Todt Battery.[31] German troops transplanted mature trees from the forests of Boulogne-sur-Mer and Desvres to camouflage the construction operations.[33]

According to the post-war accounts of Franz Xavier Dorsch who supervised the construction of the Todt battery, the construction was divided into 2 phases. First, the guns were to be ready to fire within 8 weeks, with half of its auxiliary facilities ready but without any protective cover in reinforced concrete. The battery was then to be completed in its entirety as soon as possible, without specifying an exact date, while maintaining, at all time, the gun capability to fire from their 60 mm-thick armored turrets.[31][34] The Organization Todt began the groundwork at the battery in July 1940 and began to build in August 1940 the firing platforms with circular parapets for the rotation of the armored C/39 firing platform with its 38 cm SK C/34 naval guns. Dorsch estimated at 12000 – 15000 the number of workers employed by the Organisation Todt for the construction of the heavy coastal batteries between Boulogne-sur-Mer and Calais. About 9000 of them were Germans.[22][34]

According to Dorsch, the firing platforms and all the facilities needed for the ammunition, the machinery and the crew were finalized in 8 weeks and three days. Winston Churchill, in his book "The Second World War", recorded that the British had already identified the Todt, Friedrich August, Grosser Kurfürst, Prinz Heinrich and Oldenburg batteries, together with fourteen other 17-cm guns, were "by the middle of September [1940] mounted and ready for use in this region alone", around Calais and Cape Gris-Nez.[35]

Dorsch considered that three factors contributed to making the battery combat-ready in about two months. Firstly, most of the workers could be immediately accommodated in the Nissen huts of the former British camp of Etaples, about 15 km southwest of Boulogne. Secondly, the camouflage of the construction site was kept minimal given the size of the future casemates, which allowed the swift progress of the construction. Thirdly, suitable construction aggregates were found in large quantities within a radius of about 15 km from the site.[34]

The Organisation Todt had to improve the road network in the surrounding area to transport the building materials with up to 1200 heavy trucks. A dedicated road was built between the construction site and the largest source of gravel in the nearby quarries of Hidrequent-Rinxent, near Marquise, avoiding towns when possible and building a new bridge above the road Boulogne-Calais to not disrupt the traffic of this strategic road. The road from the train station of Wimereux to Audinghem had to be upgraded to allow the transport of the guns. Two Sd.Kfz. 9 half-tracks towed the guns, weighing more than 70 tons, loaded on Culemeyer-type heavy trailers, developed by the Gothaer Waggonfabrik, with 48 wheels on 12 axles and a capacity up to 100 tons.[34][36]

The Organisation Todt could also use a fully equipped sawmill in Outreau, south of Boulogne-sur-mer, to produce the large quantities of formwork needed for the reinforced concrete structures and to transport it to the construction site.[34] The formwork for the ceiling of the casemate was supported by a temporary falsework above the firing platform that had to remain combat-ready during its construction. This temporary falsework was later removed once the reinforced concrete had sufficiently hardened to support itself and was used to building the next casemate of the battery.[34]

In November 1941, the casemates were completed after pouring 12,000 cubic meters of concrete and using 800 tonnes of reinforcing bars to build each SK (Sonderkonstruktion) casemates.[37][38][23] No shots were fired by the battery between September 1940 and January 1942.[22][34]

Firing chamber

The pivot of the armored turreted 38 cm SK C/34 naval gun was at the center of an open vast circular room with an internal diameter of 29 m, under an 11-meter high ceiling. Two continuous concrete benches are running along the rear wall of the casemate. The lower one supports the rotating turret. The railroad track connecting the casemate to the main ammunition bunkers located at Onglevert arrived at the level of the higher bench through two 2 meters-wide openings.

Between the two benches runs a circular corridor equipped with two concentric Decauville-type rails. The inner track supported the rollers of the turret loading crane, while the second track was used to move trolleys with shells and propelling charges. Two passages gave access for servicing the shaft.

The embrasure of the casemate allowed a 120° rotation of the turret, a -4° to 60° elevation for the gun.[23] This large embrasure was protected, on its sides, by 4 cm thick armored plates following as closely as possible the shape of the rotating turret and, on its higher part, by a "Todt front" reinforced with thick steel plates, removed by scrap metal dealers after the war.[23]

Garrison

The Kriegsmarine maintained a separate coastal defense network during World War II. It established early 1940 several sea defense zones to protect the large amount of coastline which Germany had acquired after invading the Low Countries, Denmark, Norway, and France.[39] In spring 1940, the Kriegsmarine began to reorganize coastal defense around sea defense zones. Logistically, the sea defense zones and its separate coastal defense network were strictly a Navy command but were eventually integrated into the Atlantic Wall which was generally overseen by the German Army.[39]

The Todt battery was under the orders of the seekommandant Pas-de-Calais, Vice Admiral Friedrich Frisius, who also commanded the other coastal batteries. The 242nd Coastal Artillery Battalion of the Kriegsmarine (Marine-Artillerie-Abteilung 242 – MAA 242) manned the battery with a garrison of some 390 men (4 officers, 49 NCOs and 337 sailors). The battery was commanded from 1940 to 1942 by Kapitänleutnant MA Wilhelm Günther and from 1942 until its capture on 29 September 1944 by Oberleutnant MA Klaus Momber.[22]

Fire control

.jpg.webp)

The casemates were not equipped with sighting elements. The firing coordinates were given to the casemates by the fire control post located in a regelbau S100 bunker[41] along the shoreline at Cran-aux-Oeufs, 1,200 m (3,900 ft) north of the battery (50°50′50.45″N 1°35′4.37″E). The command center, two personnel bunkers, a water reservoir with its close-combat defensive positions at Cran-aux-Oeufs formed the strongpoint Widerstandsnest (Wn) 166a Seydlitz.[42] This command center was equipped with a 10.5-meters optical coincidence rangefinder under a steel cupola. A direction finder and active ranging radar FuMO 214 Würzburg Riese was installed on top of one of the personnel bunkers.[42]

Target information was also provided by both spotter aircraft and by naval radar sets installed at Cap Blanc-Nez and Cap d’Alprech, south of Outreau, known as DeTe-Gerät (Dezimeter Telegraphie-Gerät, decimetric telegraphy device).[43] These units were capable of detecting targets out to a range of 40 km (25 mi), including small British patrol craft inshore of the English coast. Two additional radar sites were added by mid-September 1940: a DeTe-Gerät at Cap de la Hague and a FernDeTe-Gerät long-range radar at Cap d’Antifer near Le Havre.[44]

380-mm cannons

The 38 cm SK C/34 naval gun was developed by Germany mid to late 1930s to arm the Bismarck-class battleship. Bismarck's and Tirpitz's main battery consisted of eight 38 cm SK C/34 guns in four twin turrets.[45] As with other German large-caliber naval rifles, these guns were designed by Krupp and featured sliding-wedge breechblocks, which required brass cartridge cases for the propellant charges. Under optimal conditions, the rate of fire was one shot every 18 seconds, or three per minute.[46] Under battle conditions, Bismarck averaged roughly one round per minute in her battle with HMS Hood and Prince of Wales.[47]

The Kriegsmarine also planned to use these naval guns as the armament of the three planned battleships, with a displacement of 35,400 tons, which were tentatively named "O", "P" and "Q".[48] The ships' main armament batteries were to have consisted of six 38 cm SK C/34 guns mounted in three twin turrets.[49] By 1940, project drawings for the three battle-cruisers were complete. They were reviewed by both Hitler and Admiral Raeder, both of whom approved. However, outside "initial procurement of materials and the issuance of some procurement orders",[50] the ships' keels were never laid.[50] In large part, this was due to severe material shortages, especially of high-grade steel, since there were more pressing needs for these materials for the war effort. Besides, the dockyard personnel necessary for the ships' construction were by now occupied with more pressing work, primarily on new U-boats.[51]

Spare guns were used as coastal artillery in Denmark, Norway and France. The coastal defense version of the SK C/34 was modified with a larger chamber for coast defense duties to handle the increased amount of propellant used for the special long-range Siegfried shells.[53] Gander and Chamberlain quote a weight of only 105.3 t (103.6 long tons; 116.1 short tons) for these guns, presumably accounting for the extra volume of the enlarged chamber.[54] An armored single mount, the Bettungsschiessgerüst (Firing platform) C/39 was used by these guns. It had a maximum elevation of 60° and could traverse up to 360°, depending on the emplacement. The C/39 mount had two compartments; the upper housed the guns and their loading equipment, while the lower contained the ammunition hoists, their motors, and the elevation and traverse motors. The mount was fully powered and had an underground magazine.[24] C/39 mounts were also installed at the Hanstholm fortress in Denmark, and the Vara fortress in Kristiansand, Norway. Plans were made to install two of these mounts at Cap de la Hague and two at Paimpol in France, modifying guns originally intended for an abortive refit of Gneisenau, but were not executed for unknown reasons. Work on putting two more mounts at Oxsby in Denmark was well advanced but incomplete by the end of the war. Some modified SK C/34 guns also saw service as 38 cm Siegfried K (E) railway guns, one of these being captured by American forces during the Rhône Valley campaign in 1944.[55] Like the 38 cm SK C/34 naval guns deployed as coastal defense, the 38 cm Siegfried K guns were modified with a larger chamber to handle the increased amount of propellant used for the special long-range Siegfried shells.[53] The gun could not traverse on its mount, relying instead on moving along a curving section of track or on a Vögele turntable to aim.[55]

The battery Todt was equipped with four 38 cm SK C/34 naval guns and their corresponding C/39 Firing platform. With a range up to 55.7 km (34.6 miles),[1] the guns were capable of reaching Dover and the British coast located less than 30 km from Cape Griz-Nez. Normally these were placed in open concrete barbettes, relying on their armor for protection, but Hitler thought that there was not enough protection for Todt Battery and ordered a concrete casemate 3.5 m (11 feet) thick built over and around the mounts. This had the unfortunate effect of limiting their traverse to 120°.[56]

The guns of the Todt Battery weighed 105.3 tons and had a total length of 19.63 m (64.4 feet).[54][56] The 15.75 m-long (51.7-foot) barrel was progressively rifled with 90 right-handed twisted grooves.[56] Although the range of the gun elevation was -4° to 60°, its loading had to be performed horizontally, i.e. at an elevation of 0°.

In 1949, France exchanged 3 German 38 cm SKC/34 naval guns from the Todt Battery with three French 380 mm/45 Modèle 1935 naval guns intended for the battleship Jean Bart. These French guns were originally transported to Norway following the decision in March 1944 to install them, using the C/39 armored single mounts, in the Vardåsen coastal battery at Nøtterøy (M.K.B. 6/501 "Nötteröy").[57][58][59]

Ammunition

The 38 cm SK C/34 guns of the Todt battery could fire five types of shells, four of which developed by the Kriegsmarine and one by the Heer.

The Kriegsmarine shells weighted 800 kg (1,800 lb) and had a range of 40 km (44,000 yards) with an initial speed of 820 m/s (2,700 ft/s). A lighter version was developed for the coastal batteries to increase the operational life of the barrel from about 200 rounds to 350 rounds.[60]

Developed by the Wehrmacht, the Siegfried shell (German: Siegfried Granate) was almost 40 percent lighter could be fired with a reduced charge at 920 m/s (3,000 feet per second) out to 40 km (44,000 yards). With a full charge it reached 1,050 m/s (3,400 feet per second) and could travel 55.7 kilometres (60,900 yd) – over 34 miles.[61]

The Kriegsmarine shells were fired with a unique standard charge, divided into 2 parts for easier handling: a main charge (Hauptkartusche) and a forecharge (Vorkartusche). Fitted with a C/12 nASt percussion primer, the main charge, referenced as 38 cm Hülsenkartusche 34, weighted 105.2 kg (232 lb). It was 90 cm (35 in) high and was, at its base, 47 cm (19 in) in diameter.[60] Weighting 101 kg (223 lb), the forecharge was 84.5 cm (33.3 in) high and had a diameter of 42 cm (17 in).[60]

The propelling charge for the Siegfried shell (Siegfried ladung) also came in two parts capable to fire with a light load (Siegfried Hauptkartusche) or with a full load (Siegfried Hauptkartusche) with its forecharge (Siegfried Vorkartusche). The Siegfried Hauptkartusche weighted 133 kg (293 lb) and its forecharge 123 kg (271 lb).[62]

In both cases, the main charge was in the form of a yellow brass casing while the additional load was contained in a fiber-reinforced cellulose bag.[63]

The loading was carried out in the following order: shell, Vorkartusche, then Hauptkartusche.

| German designation | Description | Dimensions | Weight | Filling weight | Muzzle velocity | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 38 cm Spr. gr L/4.6 K.z. (m.Hb) | High Explosive (HE) shell fitted with a Kz. C/27[65] nose fuse and ballistic cap | 174.8 cm (68.8 in) | 800 kg (1,800 lb) | Unknown | 820 m/s (2,700 ft/s) | 35.6 km (22.1 mi) at 30° |

| 38 cm Spr. gr L/4.5 Bd.z. (m.Hb) | HE shell fitted with a Bd.Z C/38[65] base fuse and with ballistic cap | 168.0 cm (66.1 in) | 800 kg (1,800 lb) | Unknown | 820 m/s (2,700 ft/s) | 35.6 km (22.1 mi) at 30° |

| 38 cm Spr. gr. L/4,4 Bd.z. u. K.z. (m.Hb) | Nose- and base-fused HE shell with ballistic cap | 167.2 cm (65.8 in) | 510 kg (1,120 lb) | Unknown | 1,050 m/s (3,400 ft/s) | Unknown |

| 38 cm Pzgr. L/4.4 Bd.z. (m.Hb) | Base-fused Armor-piercing shell with a ballistic cap | 167.2 cm (65.8 in) | 800 kg (1,800 lb) | Unknown | 820 m/s (2,700 ft/s) | 35.6 km (22.1 mi) at 30° |

| 38 cm Si.Gr L/4.5 Bd.z. u. K.z. (m.Hb) | Nose- and base-fused HE shell with ballistic cap (light load) | 171.0 cm (67.3 in) | 495 kg (1,091 lb) | 69 kg (152 lb) TNT | 920 m/s (3,000 ft/s) | 40.0 km (24.9 mi) |

| 38 cm Si.Gr L/4.5 Bd.z. u. Kz (m.Hb) | Nose- and base-fused HE shell with ballistic cap (full load) | 171.0 cm (67.3 in) | 495 kg (1,091 lb) | 69 kg (152 lb) TNT | 1,050 m/s (3,400 ft/s) | 55.7 km (34.6 mi) |

Service history

Although the guns were already operational in September 1940, the battery went into action, for the first time, two days after its inauguration ceremony on 12 February 1942, providing counter-battery fire, to support the return of the battleships Gneisenau and Scharnhorst, the two Scharnhorst-class battleships, the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen and escorts to German bases through the English Channel.[28]

They were not silenced until 1944, when the batteries were overrun by Allied ground forces. They caused 3,059 alerts, 216 civilian deaths, and damage to 10,056 premises in the Dover area. However, despite firing on frequent slow-moving coastal convoys, often in broad daylight, for almost the whole of that period (there was an interlude in 1943), there is no record of any vessel being hit by them, although one seaman was killed and others were injured by shell splinters from near misses.[14]

Capture

Following the victory of Operation Overlord and the break-out from Normandy, the Allies judged it essential to silence the German heavy coastal batteries around Calais which could threaten Boulogne-bound shipping and bombard Dover and inland targets.[66] In 1944 the Germans had 42 heavy guns in the vicinity of Calais, including five batteries of cross-channel guns, the Todt Battery (four 380 mm guns), Batterie Lindemann (four 406 mm guns at Sangatte), Batterie Wissant (150 mm guns near Wissant), Grosser Kurfürst (four 280 mm guns) and Gris-Nez (three 170 mm guns).[67][68] The Germans had broken the drainage systems, flooding the hinterland and added large barbed wire entanglements, minefields and blockhouses.[69]

The first attempt by elements of the 7th Canadian Infantry Brigade to take Cape Gris-Nez from 16 to 17 September failed.[70] As part of Operation Undergo, the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division led the attack on the two heavy batteries at Cape Gris-Nez which threatened the sea approaches to Boulogne. The plan devised by General Daniel Spry was to bombard them from land, sea and air to "soften up" the defenders, even if it failed to destroy the defenses. Preceded by local bombardments to keep the defenders under cover until too late to be effective, infantry assaults would follow, accompanied by flame-throwing Churchill Crocodiles to act as final "persuaders". Kangaroo armored personnel carriers would deliver infantry as close to their objectives as possible.[68]

The 9th Canadian Infantry Brigade, with armoured support from the 1st Hussars (6th Armoured Regiment), was deployed to Cape gris-Nez to take the three remaining heavy batteries. They were also supported by the British 79th Armoured Division and its mine flail tanks, Churchill Crocodiles and Churchill AVRE (Armoured Vehicle Royal Engineers), equipped with a 230 mm spigot mortar designed for the quick leveling of fortifications.

While the Highland Light Infantry of Canada attacked the batteries Grosser Kurfürst at Floringzelle and Gris-Nez about 2 km (1.2 mi) north, the North Nova Scotia Highlanders faced the Todt battery protected by minefields, barbed wire, blockhouses and anti-tank positions.[71]

The infantry assault was preceded by two intense aerial bombardments by 532 aircraft from RAF Bomber Command on 26 September and by 302 bombers on 28 September that dropped 855 tons on the Gris-Nez positions.[72] Although these probably weakened the defenses as well as the defenders' will to fight, cratering of the ground impeded the use of armor, causing tanks to bog down. Accurate shooting by the British cross-Channel guns Winnie and Pooh, two BL 14-inch Mk VII naval guns positioned behind St Margaret's, disabled the Grosser Kurfürst battery that could fire inland.[73][68]

On 29 September, the artillery opened fire at 6:35 a.m. and the infantry attack began after ten minutes behind a creeping barrage that kept the defenders under cover. The Todt battery fired for the last time. The North Nova Scotia Highlanders encountered little resistance, reaching the gun houses without opposition. The concrete walls were impervious even to AVRE petard mortars but their noise and concussion, along with hand grenades thrown into embrasures, induced the German gunners to surrender by mid-morning. The North Nova Scotia Highlanders continued on to capture the fire control post at Cran-aux-Oeufs.[74] Despite the impressive German fortifications, the defenders refused to fight on and the operation was concluded at relatively low cost in casualties.[73][75][72][76][77][78]

Post-war and museum

In August 1945, two French visitors accidentally triggered a massive explosion in Casemate 3, which pushed out part of the sidewall and caused the ceiling to collapse.[79]

Soon after the end of the war, the battery was disarmed. The guns it housed were torched by scrap merchants. The French Ministry of Armed Force became the owner of the battery but a few years later sold the land to farmers who left the bunkers abandoned. Left abandoned, the casemate were gradually invaded by wild vegetation and flooded with water. Today, the four casemates are located on private land. They are still visible and accessible. Only casemate 3, partially destroyed following its explosion in 1945, is not easily accessible.[23]

Nature protection area

Before World War II, Cape Gris-Nez had a typical agricultural landscape of bocage on the Channel coast. The agricultural parcels were delimited with dry stone walls and hedgerows separated the cultivated areas from the grassland used for the grazing of sheep and cows. There were no woodlands and small farms were all built in depressions, sheltered from the winds.[80][81]

The landscape changed considerably during the Second World War. In August 1940, the German army completely vacated the Cape Gris-Nez and its surroundings. The local population had to leave and almost all the old buildings were demolished to make way for the construction of an offensive military structures in support of Operation Sea Lion and, later, for the construction of the Atlantic Wall. To build these military works, all the dry stone walls and farm buildings were dismantled or demolished. Allied bombing raids took out the remaining buildings. Man-made woods were planted to camouflage these structures, such as the Haringzelles Woods around the Todt Battery.[80]

At the end of the war, Cape Gris-Nez looked like a moonscape, dotted with deep holes left by Allied bombing. These bomb holes nowadays shelter ponds suitable for protected amphibians. Several bombed areas were classified as dangerous zones by the French authorities. Turning the land over was forbidden. Large areas were left to pasture. The woods planted by the Germans, also bombed, are still unexploitable today and have been left in the same state since the war. They have since become unique biotopes.[80]

Dozens of varying-sized bunkers were quickly abandoned, demolished or otherwise left to become derelict, allowing nature to slowly take over. Most of the large German military structures were not demolished after the war and became ideal locations for bats for shelter, breeding and hibernation during wintertime.[80][82] In 1963, the site known as "Anse du Cap Gris-Nez" was included in the French inventory of protected sites.

As a consequence of the 1973 oil crisis, Prime Minister Pierre Messmer initiated in June 1974 the construction of 13 nuclear power plants aimed at generating all of France's electricity from nuclear power.[83][84] The French electric utility company Electricité de France (EDF) started to look for possible sites in France. In the Pas-de-Calais, the sites of Gravelines, Cape Gris-Nez and Dannes were initially considered but only the projects of Graveline and Cape gris-Nez were further pursued by EDF.[85] At Cape Gris-Nez, the project called for the power plant to be located at the Cran-aux-Oeufs, digging it into the cliff. The cooling water was to be pumped form the English Channel and the hot water was to be discharged back into the sea through a canal that would open up at the Tardinghen marshes in the north.[85] In 1976, the project to build the nuclear power station at Cran-aux-Oeufs was finally abandoned, while the Gravelines Nuclear Power Station entered into service in 1980.[86][87]

The entire Cape Gris-Nez was finally protected in 1980. The cliffs of Cran-aux-Oeufs and the Haringzelles wood, in which the casemates of the Todt Battery are now scattered, were designated Natura 2000.[82] They are today part of the protected natural site "Grand Site des Deux Caps", labelled a Grand Site de France since 29 March 2011, and integrated into the larger Parc naturel régional des caps et marais d'Opale created in 2000.

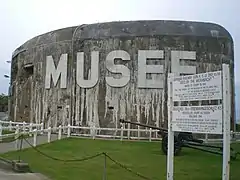

Musée du Mur de l'Atlantique

Claude-David Davies, the owner of a hotel-restaurant in Wissant, bought the land on which Casemate 1 was located to open it to the public and turn it into a museum. The work required to open the site to the public was considerable. Buckets and shovels had to be used to remove years of accumulated mud. The ground was drained and the water pumped out after stopping most of the water infiltration. With the help of several people and after three years of work, the private museum about World War II, Musée du Mur de l'Atlantique, opened its doors in 1972. An exterior metal staircase, later dismantled, replaced the old concrete one destroyed in 1944 that gave access to the roof, which was surrounded by a guardrail and open to the public. The interior of the casemate has been progressively transformed into showrooms for weapons, various equipment and even some vehicles such as motorcycles or small trucks. The exhibits today include military hardware, posters and uniforms remembering the Atlantic Wall.[88][89]

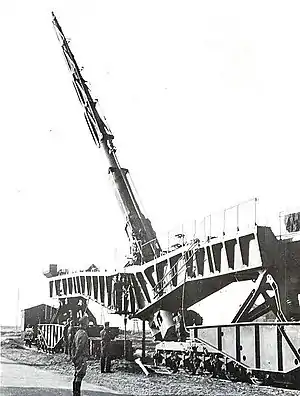

Outside the museum, one of two surviving German Krupp 28 cm K5 railway gun is displayed on an iron track, alongside military vehicles and tanks. At the beginning of the 1980s, the existence of this 28 cm K5(E) Ausführung D (model D) cannon, originally stationed at Fort Nieulay (Stp 89 Fulda) in Calais, became known to the founder of the museum.[90][91] After years of negotiations with the French army, the K5 cannon was transported in 1992 from the Atelier de Construction de Tarbes (A.T.S) in Tarbes to the north of France.[92][93][89] The origin of the cannon is not clear but it is believed that it was captured in the Montélimar pocket in southern France when the cannons of the EisenbahnBatterie 749 were captured.[94][91]

Numerous objects from the Second World War are also displayed outside the casemate 1, among which one 8.8 cm Flak 18/36/37/41 anti-aircraft gun, a half-track armored personnel carrier OT-810 (a Czechoslovak post-war version of the SdKfz 251), a 75-mm 7.5 cm Pak 40 anti-tank gun, a Belgian gate (anti-tank steel fence) and several Czech hedgehogs and anti-tank tetrahedra.

Gallery

One of the battery's 38 cm guns during World War II.

One of the battery's 38 cm guns during World War II. K5 28 cm railway gun, at the museum.

K5 28 cm railway gun, at the museum. Another view of the Todt Battery

Another view of the Todt Battery Bunker in 1993.

Bunker in 1993. Bunker housing the museum.

Bunker housing the museum. Diorama showing the battery's four bunkers.

Diorama showing the battery's four bunkers. The Todt Battery in 2008

The Todt Battery in 2008

See also

References

- Christopher 2014, p. 95.

- Bungay 2000, pp. 31–33.

- Overy 2013, pp. 68–69.

- Murray & Millet 2000, p. 84.

- Murray & Millet 2000, p. 66.

- CARL 2008, pp. 106–107.

- CARL 2008, p. 107-110.

- Cox 1977, p. 160.

- Schenk 1990, p. 323.

- CARL 2008, p. 109.

- Three of these dombunkers still exist today. The first was located at Pointes aux Oies, near Wimereux (50°47′3.15″N 1°37′18.14″E), the second in the Vallée Heureuse, near Hydrequent (50°48′50.04″N 1°45′17.17″E and the third at Fort Nieulay in the suburbs of Calais (50°57′15.83″N 1°49′53.63″E).

- Zaloga 2007, p. 6-7.

- Schenk 1990, p. 324.

- Hewitt 2008, p. 109.

- Bungay 2000, p. 339.

- CARL 2008, p. 127-130.

- Fleming 1957, p. 273.

- Corum 1997, p. 283–284.

- CARL 2008b, p. 10-15.

- CARL 2008b, p. 21-26.

- CARL 2008b, p. 99-102.

- "Stp 166 Saitenspiel/Marineküstenbatterie Todt". The German 15th army at the Atlantic wall. Archived from the original on 23 July 2020. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- Delefosse, Yannick; Delefosse, Chantal (1978). "La Batterie Todt". Gazette des Armes (in French). Régi'Arm (59): 33–37. Archived from the original on 24 July 2020. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- Hogg 1997, p. 242.

- The two ammunition bunkers still exists today (50°50′30.81″N 1°37′23.05″E and 50°50′32.7″N 1°37′18.09″E)

- "Wn 183 Eber / Radars of Stp 178 Kellergeist". The German 15th army at the Atlantic wall. Archived from the original on 3 May 2020. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- Gilbert 1989, p. 199.

- Williams 2013.

- Chandler 1994, p. 41.

- Forty 2002, p. 32.

- Dorsch, Xaver; Robinson, J.B.; Ross, W.F. (1947). Organization Todt. Historical Division, US Army European Command, Foreign Military Studies Branch.

- Forty 2002, p. 6.

- "Bois d'Haringzelles" (in French). Eden62. Archived from the original on 27 September 2020. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- Walendy 1987, p. 30-31.

- Churchill 1970, p. 238–240.

- Moret, Jean-Charles. "Le musée de la batterie allemande TODT – Cap Gris Nez – Calais- France | Association Fort de Litroz" (in French). Archived from the original on 30 November 2020. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- Desquesnes, Rémy (1992). "L'Organisation Todt en France (1940–1944)". Histoire, Économie et Société (in French). 11 (3): 535–550. doi:10.3406/hes.1992.1649. ISSN 0752-5702. JSTOR 23611258.

- Kaufmann et al. 2012.

- Lohmann & Hildebrand 1956.

- Forty 2002, p. 21.

- "Ständige Regelbauten im Bereich AOK15". The German 15th army at the Atlantic wall. Archived from the original on 13 July 2013. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- "Wn 166a Seydlitz". The German 15th army at the Atlantic wall. Archived from the original on 24 July 2020. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- Sieche, Erwin (1978). "German Naval Radar to 1945". Warship (22). Archived from the original on 11 May 2016. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- Schenk 1990, p. 324–325.

- Gröner, pp. 34–35.

- Garzke & Dulin, p. 274.

- Campbell 2002, pp. 229–30.

- Shirokorad, Alexander (2010). Атлантический вал Гитлера [Hitler's Atlantic Wall]. Military secrets of the XX century (in Russian). ISBN 978-5-4444-8129-5. Archived from the original on 4 August 2017. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

- Campbell 2002, p. 229–230.

- Garzke & Dulin, p. 354.

- Gardiner & Chesneau, p. 220.

- Campbell 2002, p. 229.

- Gander & Chamberlain 1979, p. 272.

- François 2006, p. 75.

- Gander & Chamberlain 1979, p. 256.

- Zaloga 2011, p. 45.

- "Artillery units in Norway 1940–45". nuav.net. Archived from the original on 10 August 2020. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- Wahl 2007.

- Oberkommando der Kriegsmarine 1941a.

- Hogg 1997, pp. 242–243.

- Hogg 1997, p. 387.

- Oberkommando der Kriegsmarine 1941b.

- Oberkommando der Kriegsmarine 1941c.

- Army Council (10 February 1945). "Kz. C/27 (Lm)". Handbook of Enemy Ammunition. Pamphlet 14. War Office. Archived from the original on 21 February 2021. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- Stacey & Bond 1960, pp. 346, 344.

- Stacey & Bond 1960, p. 352.

- Copp, Terry (2006a). "Canadian Operational Art: The Siege of Boulogne and Calais" (PDF). The Canadian Army Journal. 9 (1): 29–49. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 September 2020. Retrieved 29 July 2020.

- Copp 2006, p. 76.

- Stacey & Bond 1960, pp. 345–346.

- Stacey & Bond 1960, pp. 352–353.

- Stacey, C P (1966), "The Cape Gris-Nez Batteries", Volume III The Victory Campaign: The Operations in North-West Europe, 1944–1945, Official History of the Canadian Army in the Second World War, Department of National Defence, pp. 336–344, archived from the original on 28 October 2012, retrieved 20 July 2020 – via Hyperwar Foundation

- Copp 2006, p. 82.

- Stacey & Bond 1960, p. 353.

- Stacey & Bond 1960, p. 354.

- Whitlock, Flint (2015). "Smashing Hitler's Atlantic Wall". WWII Quarterly Magazine: 42–55.

- Zaloga 2007, p. 20.

- "No. 44 Calais Cleared". Canadian Army Newsreel. Canadian Army Film Unit. 1944. Archived from the original on 8 September 2020. Retrieved 29 July 2020 – via YouTube.

(...); the 1st Canadian Army attack the fort at Cap Gris-Nez in September 1944; (...) Cap Gris-Nez Garrison; cross-channel guns are disabled.

- Schmeelke & Schmeelke 1998, p. 38.

- "Site Natura 2000 FR 3100478 (NPC 005) Falaises du cran aux oeufs et du Cap Gris-nez, dune du châtelet, marais de Tardinghen, dunes de Wissant (Document d'objectifs Parties A et B)" (PDF) (in French). 2005. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 February 2021. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- "DOCOB site Natura 2000 NPC 005 (FR 3100478)". hauts-de-france.developpement-durable.gouv.fr. Archived from the original on 11 August 2020. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- INPN. "Natura 2000 FSD – FR3100478 – Falaises du Cran aux Oeufs et du Cap Gris-Nez, Dunes du Chatelet, Marais de Tardinghen et Dunes de Wissant – Description". inpn.mnhn.fr. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- Thomas Ferenczi, Le gaulliste Pierre Messmer est mort Archived 8 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Le Monde, 29 August 2007 (in French)

- Interview of Pierre Messmer Archived 30 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine on 3 June 1974 (film), on the French government's website (in French)

- Vivier, Emile. "Histoire grands combats". Nord Nature (in French). Archived from the original on 15 February 2020. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- Sueur, Georges (29 July 1975). "UNE CENTRALE NUCLÉAIRE AU CAP GRIS-NEZ " Ce serait un crime " affirme la Fédération Nord-Nature". Le Monde (in French). Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- Bertrand, Xavier (21 March 2018). "Quand l'Etat voulait implanter une centrale nucléaire… au Cap Gris-Nez". DailyNord. Archived from the original on 9 August 2020. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- Ferrard, Stéphane; Delefosse, Chantal (1978). "Le Musée du Mur de l'Atlantique". Gazette des Armes (in French). Régi'Arm (61): 39–41. Archived from the original on 24 July 2020. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- "Les gardiens de la mémoire" (PDF). Vue des Caps. 8. 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 February 2021. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- "Stp 89 Fulda". The 15th German army at the Atlantikwall. Archived from the original on 3 May 2020. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- Wijnstok 2015, p. 33.

- Archives Municipales de Tarbes. "Panneau qui se trouvait dans l'enceinte de l'arsenal : "Canon allemand K5 de 280, artillerie de marine sur voie ferrée, fabrication Krupp 1943...."". archives.tarbes.fr (in French). Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- "Canon allemand". claude.larronde.pagesperso-orange.fr (in French). 16 February 2004. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- Zaloga 2016, p. 28.

Bibliography

- Bungay, Stephen (2000). The Most Dangerous Enemy : A History of the Battle of Britain. London: Aurum Press. ISBN 1-85410-721-6.

- Campbell, John (2002). Naval Weapons of World War Two. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-87021-459-4.

- Chandler, David (1994). The D-Day encyclopedia. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-13-203621-5.

- Christopher, John (2014). Organisation Todt From Autobahns to Atlantic Wall: Building the Third Reich. Amberley Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-1-4456-3873-7.

- Churchill, Winston (1970) [first published 1949]. The Fall of France: May 1940 – August 1940.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Copp, Terry (2006). Cinderella Army: The Canadians in Northwest Europe, 1944–1945. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-3925-5.

- Corum, James (1997). The Luftwaffe: Creating the Operational Air War, 1918–1940. Kansas University Press. ISBN 978-0-7006-0836-2.

- Cox, Richard (1977). Operation Sea Lion. Presidio Press. ISBN 0-89141-015-5.

- Fleming, Peter (1957). Invasion 1940: An Account of the German Preparations and the British Counter-measures. R. Hart-Davis.

- Forty, George (2002). Fortress Europe : Hitler's Atlantic wall. Hersham, Surrey: Ian Allan. ISBN 978-0-7110-2769-5.

- François, Guy (2006). Eisenbahnartillerie : histoire de l'artillerie lourde sur voie ferrée allemande des origines à 1945. Paris: Éd. Histoire et Fortifications. ISBN 9782915767087.

- Fuhrer Directives and other Top-Level Directives of the German Armed Forces, 1939–1941. World War II Operational Documents (Combined Arms Research Library Digital Library ed.). Washington, DC: U.S. Office of Naval Intelligence. 2008 [1948]. OCLC 464601776. N16267-A. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- Fuehrer directives and other top-level directives of the German Armed Forces, 1942–1945. World War II Operational Documents (Combined Arms Research Library Digital Library ed.). Washington, DC: U.S. Office of Naval Intelligence. 2008 [1948]. OCLC 464601776. N16267-A. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- Gander, Terry; Chamberlain, Peter (1979). Weapons of the Third Reich: An Encyclopedic Survey of All Small Arms, Artillery and Special Weapons of the German Land Forces 1939–1945. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-15090-3.

- Gardiner, Robert; Chesneau, Roger, eds. (1980). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1922–1946. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-913-9. OCLC 18121784.

- Garzke, William H.; Dulin, Robert O. (1985). Battleships: Axis and Neutral Battleships in World War II. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-101-0. OCLC 12613723.

- Gilbert, Martin (1989). The Second World War : a complete history. New York: H. Holt. ISBN 0-8050-0534-X.

- Gröner, Erich (1990). German Warships: 1815–1945. Vol. I: Major Surface Vessels. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-790-6.

- Hewitt, Geoff (2008). Hitler's Armada: The Royal Navy and the Defence of Great Britain, April – October 1940. Pen & Sword Maritime. ISBN 978-1844157853

- Hogg, Ian V. (1997). German Artillery of World War Two (2nd corrected ed.). Mechanicsville, PA: Stackpole Books. ISBN 1-85367-480-X.

- Kaufmann, J. E.; Kaufmann, H.W.; Jankovic-Potocnik, A.; Tonic, Vladimir (2012). The Atlantic Wall: History and Guide. Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-1-78337-838-8.

- Lohmann, Walter; Hildebrand, Hans H (1956). Die deutsche Kriegsmarine, 1939–1945: Gliederung, Einsatz, Stellenbesetzung (in German). Bad Nauheim: H.H. Podzun. OCLC 61588484.

- Murray, Williamson; Millet, Alan R. (2000). A war to be won : fighting the Second World War. Cambridge, Mass: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-00680-5.

- Oberkommando der Kriegsmarine (1941a). Munitionsvorschriften für die Kriegsmarine (Artillerie) – Hülsenkartusche. M.Dv. Nr. 190 (in German). Vol. 4A1. Berlin.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Oberkommando der Kriegsmarine (1941b). Munitionsvorschriften für die Kriegsmarine (Artillerie) – Vorkartusche. M.Dv. Nr. 190 (in German). Vol. 4A6. Berlin. OCLC 860710635.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Oberkommando der Kriegsmarine (1941c). Munitionsvorschriften für die Kriegsmarine (Artillerie) -Panzersprenggranaten mit Haube – a) Psgr (m.Hb). M.Dv. Nr. 190 (in German). Vol. 1A1. Berlin. OCLC 860710635.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Overy, Richard J. (2013). The Bombing War : Europe 1939–1945. London & New York: Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-7139-9561-9.

- Schenk, Peter (1990). Invasion of England 1940: The Planning of Operation Sealion. Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-548-9.

- Schmeelke, Karl-Heinz; Schmeelke, Michael (1998). Schwere Geschütze am Kanal : Bereich Calais/Boulogne ; 17 cm, 19,4 cm, 24 cm, 28 cm, 30,5 cm, 38 cm, 40,6 cm. Podzun-Pallas. ISBN 3-7909-0635-2. OCLC 75954782.

- Stacey, C. P.; Bond, C. C. J. (1960). The Victory Campaign: The operations in North-West Europe 1944–1945 (PDF). Official History of the Canadian Army in the Second World War. Vol. III. The Queen's Printer and Controller of Stationery Ottawa. OCLC 606015967. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 December 2020. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- Wahl, Jean-Bernard (2007). "Installés par les Allemands en batterie côtière en Norvège, retour en France des canons de 380 du Jean-Bart". Magazine 39-45 (in French) (244): 44–57.

- Walendy, Udo (1987). "Die Organisation Todt". Historische Tatsachen (in German). 32: 3–35. ISSN 0176-4144.

- Wijnstok, Jan Coen (2015). German railway gun 28 cm k5e leopold : 28 cm k5 (e). Model Centrum Progress. ISBN 978-83-60672-24-2. OCLC 951927000.

- Williams, Paul (2013). Hitler's Atlantic wall : Pas de Calais. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Battleground. ISBN 978-1-78303-666-0.

- Zaloga, Steven J. (2007). The Atlantic Wall. Oxford, UK New York, NY, USA: Osprey Pub. ISBN 978-1-84603-129-8.

- Zaloga, Steven J. (2011). The Atlantic Wall (2): Belgium, The Netherlands, Denmark and Norway. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84908-125-2.

- Zaloga, Steven J. (2016). Railway guns of World War II. Oxford New York: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4728-1068-7.

- This article was created from the translation of the article Batterie Todt the French Wikipedia, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution Share Alike 3.0 Unported and free documentation license GNU.

Further reading

- Bird, Will (1983). No retreating footsteps : the story of the North Nova Scotia Highlanders. Hantsport, Nova Scotia: Lancelot Press. ISBN 978-0-88999-214-6.

- Chazette, Alain (2006). Les batteries côtières du Nord-Pas-de-Calais : Dunkerque, Calais, Boulogne, France 40, Mur de l'Atlantique (in French). Paris: Editions Histoire et Fortifications. ISBN 9782915767070.

- Chazette, Alain (2012). Les batteries du secteur de Gris-Nez (in French). Vertou (Loire-Atlantique): Ed. Histoire & Fortifications. ISBN 978-2915767490.

- Delefosse, Yannick; Davies, David; Delefosse, Chantal (1986). La Batterie Todt: construction et historique (in French). Musée du Mur de l'Atlantique.

- Desquesnes, Rémy (2012). Le mur de l'Atlantique : les batteries d'artillerie (in French). Rennes: Éd. "Ouest-France. ISBN 978-2737352645.

- John Deane (1970). Fiasco: The Break-out of the German Battleships. Stein and Day. ISBN 9780812812763.

- Sakkers, Hans; Machielse, Marc (2013). Artillerieduell der Fernkampfgeschütze am Pas de Calais 1940–1944 : aus Sicht der schweren deutschen Marinebatterien "Großer Kurfürst", "Todt", "Prinz Heinrich", "Friedrich August", "Lindemann" und der Heeres-Eisenbahnartillerie (in German). Aachen: Helios. ISBN 978-3-86933-092-1.

- Simonnet, Stéphane (2015). Les poches de l'Atlantique janvier 1944-mai 1945 : les batailles oubliées de la Libération (in French). Paris: Tallandier. ISBN 979-1-02-100493-1.

- Virilio, Paul (2008). Bunker archéologie – étude sur l'espace militaire européen de la Seconde Guerre mondiale (in French). Paris: Galilée. ISBN 9782718607801.

External links

- Todt Battery Museum website (in French)

- Battery Todt on Bunkersite.com

- Germany 38 cm (14.96") SK C/34 (NavWeps page)