Second Battle of Independence

The Second Battle of Independence was fought on October 22, 1864, near Independence, Missouri, as part of Price's Raid during the American Civil War. In late 1864, Major General Sterling Price of the Confederate States Army led a cavalry force into the state of Missouri, hoping to create a popular uprising against Union control, draw Union Army troops from more important areas, and influence the 1864 United States presidential election.

| Second Battle of Independence | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

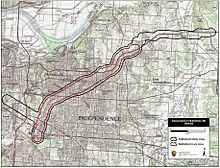

Map of the battlefield | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Alfred Pleasonton | Sterling Price | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Pleasonton's division | Army of Missouri | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 7,000 | 7,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| unknown | c. 400 | ||||||

Price was opposed by a combination of Union Army and Kansas State Militia forces positioned near Kansas City and led by Major General Samuel R. Curtis. Union cavalry under Major General Alfred Pleasonton followed Price from the east, working to catch up to the Confederates from the rear. While moving westwards along the Missouri River, Price's men made contact with Curtis's Union troops at the Little Blue River on October 21. After forcing the Union soldiers to retreat in the Battle of Little Blue River, the Confederates occupied the city of Independence, which was 7 miles (11 km) away.

On October 22, part of Price's force pushed Curtis's men across the Big Blue River 6 miles (9.7 km) west of Independence in the Battle of Byram's Ford, while Pleasonton drove back Confederate defenders from the Little Blue. Confederate troops from the divisions of Major General James F. Fagan and Brigadier General John S. Marmaduke resisted Pleasonton's advance.

Two Union brigades forced the Confederates through Independence, capturing two cannons and 300 men. While Pleasonton brought up two fresh brigades, the Confederates regrouped southwest of town. Further Union pressure drove the defenders back, and fighting continued until after dark. By the end of October 22, almost all of the Confederate forces had fallen back across the Big Blue. The next day, Price was defeated in the Battle of Westport, and his men fell back through Kansas, suffering further defeats on the way before reaching Texas.

The Confederates suffered heavy losses during the campaign. The expansion of the town (now city) of Independence into areas that were rural at the time of the battle has resulted in urban development over much of the battlefield, such that meaningful preservation is no longer possible.

Background

When the American Civil War began in April 1861, the state of Missouri did not secede despite allowing slavery, as it was politically divided. Governor of Missouri Claiborne Fox Jackson supported secession and the Confederate States of America, both of which were opposed by Union Army elements under the command of Brigadier General Nathaniel Lyon. A combination of Confederate and pro-secession Missouri State Guard forces defeated Lyon at the Battle of Wilson's Creek in August, but were confined to southwestern Missouri by the end of the year. The state also developed two competing governments, one supporting the Union and the other the Confederacy.[1] Control of Missouri passed to the Union in March 1862 after the Battle of Pea Ridge in Arkansas, and Confederate activity in Missouri was largely restricted to raids and guerrilla warfare through the rest of 1862 and into 1863.[2]

By September 1864, it was becoming clear that the Confederacy had little chance of a military victory, and incumbent President of the United States Abraham Lincoln had an edge over George B. McClellan—who supported an immediate peace—in the 1864 United States presidential election.[3] With the dire situation east of the Mississippi River in the Atlanta campaign and Siege of Petersburg, General Edmund Kirby Smith, commander of the Confederate Trans-Mississippi Department, was ordered by Confederate President Jefferson Davis's military advisor General Braxton Bragg to send his infantry across the river to more important areas of the war. Union Navy control of the Mississippi River made this impossible.

Instead, Smith decided to attack, despite having limited resources.[4] Confederate Major General Sterling Price and Confederate Governor of Missouri Thomas Caute Reynolds, who had replaced Jackson in February 1863 after the latter's death, proposed an invasion of Missouri.[4][5][6] Smith approved of the plan and placed Price in command of the offensive. The invasion was designed to start a popular uprising against Union control of the state, draw Union troops away from more important theaters of the war, and improve McClellan's chance of defeating Lincoln.[4] Smith's order tasked Price to "make St. Louis the objective point of your movement" and, if "compelled to withdraw from the State", to retreat through Kansas and the Indian Territory, gathering supplies in the process.[7]

Prelude

After entering Missouri on September 19, Price's column advanced north, only to suffer a bloody repulse at the Battle of Pilot Knob on September 27. Having suffered hundreds of casualties at Pilot Knob, Price decided not to attack St. Louis, which had been reinforced by 9,000 Union infantrymen of Major General Andrew Jackson Smith's XVI Corps.[8][9] Instead, he aimed his command west, towards the state capital of Jefferson City.[8] Encumbered by a slow-moving wagon train, Price's army took long enough to reach Jefferson City that the Union garrison could be reinforced, growing from 1,000 to 7,000 men.[10] These reinforcements were largely two cavalry brigades commanded by Brigadier Generals John McNeil (from Rolla) and John B. Sanborn (from Cuba) as well as some militia units from other parts of the state.[11] Once Price reached Jefferson City in early October, he decided that it was too strong to attack.[12] After giving up on Jefferson City, Price abandoned the idea of an occupation of Missouri and moved west towards Kansas in compliance with Smith's original orders.[13] Moving west along the Missouri River, the Confederates gathered recruits and supplies, won the Battle of Glasgow[12] and captured Sedalia.[14]

Opposing forces

Price's force, named the Army of Missouri, contained about 12,000 or 13,000 cavalrymen and 14 cannons.[15][16] Several thousand of these men were either not armed or poorly armed, and all of Price's cannons were of light caliber. The Army of Missouri was organized into three divisions, commanded by Brigadier Generals Joseph O. Shelby and John S. Marmaduke and Major General James F. Fagan.[15][16] Marmaduke's division contained two brigades, commanded by Brigadier General John B. Clark Jr. and Colonel Thomas R. Freeman; Shelby's division had three brigades under Colonels David Shanks (replaced by Brigadier General M. Jeff Thompson after Shanks was killed in action), Sidney D. Jackman, and Charles H. Tyler; and Fagan's division contained four brigades commanded by Brigadier General William L. Cabell and Colonels William F. Slemons, Archibald S. Dobbins, and Thomas H. McCray.[17]

Countering Price was the Department of Missouri, which was commanded by Major General William S. Rosecrans. Many of the department's 10,000 men were militia, who were scattered throughout the state in a variety of local districts and subdistricts.[18] In September, Rosecrans was reinforced at St. Louis by part of the XVI Corps, under the command of Smith.[9] A Union cavalry division was formed on October 6, in Jefferson City under the command of Major General Alfred Pleasonton. Pleasonton's command consisted of four brigades, although one of them (part of Smith's corps) was not in the area at the time.[19] The four brigades were composed of a mixture of Union Army troops and Missouri militia and were supported by 12 cannons; they were commanded by Brigadier Generals Egbert Brown, McNeil, and Sanborn and Colonel Edward F. Winslow.[20]

Sanborn temporarily commanded the formation until Pleasonton took full command on October 20.[21] On the other side of the state, the Union Army of the Border was formed under the command of Major General Samuel R. Curtis, the commander of the Department of Kansas; it consisted of a combination of Union Army soldiers and men from the Kansas State Militia. The Army of the Border was divided into two wings: one commanded by Major General George W. Dietzler and the other by Major General James G. Blunt. While Blunt's non-militia soldiers moved east towards Price, political forces in Kansas prevented the militiamen from traveling further into Missouri than the Big Blue River. Many of the militia officers were politicians allied to competing factions in the 1864 Kansas gubernatorial election, and allegations that the militia mobilization was intended to affect the election were common.[22][23]

Lexington and Little Blue River

On October 18, Blunt occupied the town of Lexington, Missouri, hoping to act in conjunction with Sanborn, but Sanborn was too far away, and Price's army was only 20 miles (32 km) to the east.[24][25] Blunt decided to hold the town and resist Price,[26] who attacked with Shelby's division on October 19, resulting in the Second Battle of Lexington. Shelby's men were not able to dislodge the Union defenders, but the Confederates captured the town after Marmaduke's and Fagan's divisions were committed to the fray.[24] The morning after the battle, Blunt halted his retreat at the Little Blue River. He advocated for a stand at the river, but he could not be reinforced at that position because of the restrictions on the movement of the Kansas State Militia. Curtis ordered Blunt to fall back to the main Union position at Independence, Missouri; only a single regiment and four cannons were left at the Little Blue as a rear guard.[27] This force totaled about 400[28] or 600 men.[29]

On the morning of October 21, Clark's Confederate brigade attacked the Union rear guard and forced its way across the river, opening the Battle of Little Blue River. Seesaw fighting followed while Blunt received permission to return his troops to the Little Blue River line and Price brought up Shelby's division.[30] The two sides formed strengthened lines, and Shelby continued the attack. Confederate threats to the Union left flank forced troops to be drawn from the center to support the threatened parts of the line. This weakening of the center of the line exposed it to Confederate attack. A little after 14:00, the Union troops began retreating from the field, falling back to Independence.[31] Late that evening, Blunt ordered Independence abandoned and withdrew his men to the Big Blue, 6 miles (9.7 km) to the west. By nightfall, Curtis's and Blunt's men were on the west side of the Big Blue, and Price had occupied Independence.[32]

Battle

From the Little Blue to Independence

_(page_67_crop).jpg.webp)

On October 22, Price made a feinting attack against the north part of the Big Blue River line, while Shelby's division attacked in force further south, bringing on the Battle of Byram's Ford. The attack forced the Union line back towards the town of Westport, and Price moved much of his army across the Big Blue.[33] Fagan's division with 4,500 men was left at Independence as a rear guard, and Marmaduke's division with 2,500 men was between Fagan and Shelby.[34] Before Pleasonton took over command from Sanborn on October 20, his cavalrymen had made little progress.[21] Rosecrans and Smith had been following the cavalry with infantry, but with Pleasonton in charge, the cavalry moved much quicker and reached Lexington a day ahead of the infantry. Knowing that Price would eventually have to turn south to return to Confederate territory, Rosecrans wanted Smith and Pleasonton to move south and cut off the path the Confederates would have to take in a retreat. Instead, Pleasonton had gotten far enough ahead of Rosecrans that his 7,000 cavalrymen were already almost to the Confederate line. On the morning of October 22, Rosecrans changed his plans to allow Pleasonton to pursue Price directly. Smith's infantry had already begun the turn south, and had to countermarch north.[35][36]

Contact between the two sides was made at 05:00 at the Little Blue. At the river crossing were Confederate pickets from Slemons's brigade. The detachment was under the command of Colonel John C. Wright.[37] The 13th Missouri Cavalry Regiment and 17th Illinois Cavalry Regiment of McNeil's brigade forced Wright's command back, but were delayed in crossing because of a burned bridge. An artillery battery was across the river by 10:00.[38][39] McNeil's brigade spent two hours pushing Slemons's brigade and Hughey's Arkansas Battery, which was armed with Parrott rifles, before them.[39][40] The Union cavalry had gone roughly 3 miles (4.8 km) of the roughly 7 miles (11 km) to Independence by 13:30.[38][41] Price and Fagan were informed of the action, and Cabell's brigade was sent to support Slemons's and Wright's rear guard action. Cabell's men moved to the front, and Slemons and Wright fell to the rear and out of the action.[42] Price's wagon train had not yet been able to fully cross the Big Blue, and Cabell had to hold out at Independence long enough to allow the train to cross, as Price was stuck between two Union forces.[38]

Confederates are driven out of Independence

McNeil resumed the advance around 14:00, using a formation consisting of the 17th Illinois Cavalry and the 13th Missouri Cavalry as his main line and the 5th Missouri State Militia Cavalry Regiment acting as skirmishers. Despite support from Hughey's battery which lasted until 15:00, Cabell's brigade was forced back to Independence itself,[43] where it was then joined by Clark's and Freeman's brigades.[38] Pleasonton committed Sanborn's brigade to the fighting, and an attack was made with the 2nd Arkansas Cavalry Regiment leading the way.[43] While coordination between McNeil and Sanborn was intended, the 2nd Arkansas Cavalry – on the right of Sanborn's brigade – had commenced their advance earlier than the rest of the attacking force, and were halfway to Independence when the rest began advancing towards the town.[44][45] After the 2nd Arkansas Cavalry entered the town, the men dismounted in preparation for hand-to-hand combat.[45] The attack drove the Confederates away to the west and southwest, but the Union forces did not pursue them due to fatigue. McNeil's men began their part of the advance once Sanborn stalled, initially heading west before turning south and then back to the west.[43] McNeil's attack was led by the 13th Missouri Cavalry, with the 17th Illinois Cavalry and the 7th Kansas Cavalry Regiment following. Confederates had attempted to block the path of this attack by stringing a chain across the road, but this obstacle was removed by a Unionist civilian.[46]

The attack of the 13th Missouri Cavalry shattered Confederate resistance at the Temple Lot, a religious site related to the Latter Day Saint movement.[44] The Union troopers also charged Hughey's battery and its supporting Confederate detachment.[47] Union fire shot down all of the battery's horses, and routed the batterymen and the supporting detachment. The detachment's commander, Hughey's two cannons (which had been captured from Union forces at the Battle of Pleasant Hill),[48] and 300 Confederates were all captured.[36] Cabell was almost captured, and lost his sword during his escape.[48] The 13th Missouri Cavalry lost only 10 men during the charge.[47] The attack was successful but could not be followed up with the troops on hand, as both McNeil's and Sanborn's brigades had become disorganized through exhaustion and confusion.[47] Furthermore, Clark's men resisted at Independence until about 17:00, when they began falling back with the knowledge that Price's supply train was crossing the Big Blue.[48] Pleasonton responded by bringing up Brown's and Winslow's brigades.[49] Brown and Winslow were to move against the Confederates while McNeil's and Sanborn's brigades remained behind in Independence to manage post-battle cleanup tasks. A local bank and hotel were taken over by McNeil and Sanborn's men for use as hospitals, and 40 of Blunt's wounded men who had been abandoned at a field hospital during the Battle of Little Blue River and then captured by the Confederates were rescued.[50]

To the Big Blue

Pleasonton intended for Brown's brigade to attack with support from Winslow's men but the attack was slow to materialize, which allowed the Confederates to reform about 1 mile (1.6 km) to the southwest of Independence. Brown finally attacked about an hour before nightfall, but with less force than intended. The plan was to attack with a front composed of the 1st, the 4th, and the 7th Missouri State Militia Cavalry Regiments, but the latter two units were blocked when Battery L, 2nd Missouri Light Artillery Regiment halted in Independence. Furthermore, the commander of the 1st Missouri State Militia Cavalry, Colonel James McFerran, remained in the rear and did not participate in the attack. Under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Bazel Lazear, the 1st Missouri State Milita Cavalry skirmished with the Confederates until the defenders placed enough pressure on Lazear's line that he requested reinforcements. Brown finally grasped the situation on the field, located the 4th and 7th Missouri State Militia Cavalry, and sent the two regiments and the artillery unit that had blocked them to the front. The strengthened Union force then attacked with only 30 minutes remaining before sundown.[51]

The Union attack drove the Confederates back 2 miles (3.2 km), but ran low on ammunition.[48] The historian Kyle Sinisi estimated that the 1st Missouri State Militia Cavalry fired 11,700 rounds during its part of the fighting, based on the strength of the regiment and a report by McFerran stating how much ammunition the unit's soldiers were issued.[52] After running low on ammunition, Brown's men moved off of the road to Westport, and allowed Winslow's brigade to move to the front.[53] The 3rd and 4th Iowa Cavalry Regiments, and the 4th and 10th Missouri Cavalry Regiments of Winslow's brigade continued fighting as darkness fell.[48] Winslow's men attacked, and quickly drove back Cabell's and Freeman's brigades. Clark formed a rear guard with his brigade and Pratt's Texas Battery, which slowed the Union attack. Though night combat was rare during the American Civil War, the 3rd Iowa Cavalry continued the advance overnight, and pushed Clark's regiments back.[54] Around 22:00, the Confederate wagon train had completed the crossing of the Big Blue,[55] and soon after that time, all of Clark's units except for the 8th Missouri Cavalry Regiment had crossed the river as well.[56] By this point, Union troops were within a few miles of the Big Blue River. After coming under fire from the 8th Missouri Cavalry, Winslow halted his brigade's pursuit at around 22:30.[57]

Aftermath

Pleasonton claimed to have captured 400 prisoners and to have found 40 dead Confederates on the field. Price stated that he lost 300 or 400 men. On the Union side, losses were heaviest in McNeil's brigade.[55] The Civil War Battlefield Guide, edited and principally written by preservationist Frances Kennedy, states that Union losses are unknown and places Price's loss at 140 men.[33] Clark stated that his men suffered heavy losses.[58]

Concerned about the safety of his wagon train, Price ordered it to move at daylight for Little Santa Fe, a community near the Missouri/Kansas state line, via Hickman Mills. Two brigades were assigned to guard the train. Marmaduke was given orders to resist Pleasonton, and Fagan's and Shelby's divisions were to attack Curtis, although many of Fagan's men were re-rerouted to guard Marmaduke's flank.[59] On October 23, Shelby and Fagan fought Blunt in the Battle of Westport. The Confederate line initially held, but the arrival of men from the Kansas State Militia turned the tide to the Union. Also, Pleasonton sent McNeil to harass the Confederate wagon train and attacked Marmaduke with the rest of his division. The Union troops broke through the line and hit the flank of the Westport line. Fighting both Curtis and Pleasonton, and with Smith's infantrymen approaching, Price fell back into Kansas. More fighting occurred during the retreat, including a disastrous Confederate rout at the Battle of Mine Creek on October 25. Union pursuit continued until the Arkansas River was reached on November 8, and Price retreated all the way to Texas. He had brought 12,000 or 13,000 men into Missouri,[15][16] and returned with only about 3,500.[60]

In the years since the engagement, the battlefield has been built over due to the growth of Independence. A 1993 study by the American Battlefield Protection Program listed the battlefield as "severely fragmented" and a 2011 study by the Civil War Sites Advisory Commission concluded that the battlefield was "beyond hope of meaningful landscape preservation".[61] As of 2011, none of the battlefield was listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and the 2011 study found that the site would not be eligible.[62] The location is part of Freedom's Frontier National Heritage Area.[63] A self-guided tour covering 10 sites related to the battlefield has been organized by the City of Independence.[64][65]

See also

- First Battle of Independence, an August 11, 1862 battle won by the Confederacy

References

- Kennedy 1998, pp. 19–25.

- Kennedy 1998, pp. 34–37, 377–379.

- Kennedy 1998, p. 343.

- Collins 2016, pp. 27–28.

- Parrish 2001, p. 49.

- "Claiborne Fox Jackson, 1861". sos.mo.gov. Missouri State Archives. Retrieved October 24, 2020.

- Sinisi 2020, p. 22.

- Kennedy 1998, pp. 380–382.

- Sinisi 2020, p. 57.

- Collins 2016, pp. 53–54.

- Sinisi 2020, pp. 103–104.

- Kennedy 1998, pp. 382–383.

- Sinisi 2020, p. 109.

- Collins 2016, p. 63.

- Kennedy 1998, p. 380.

- Collins 2016, p. 39.

- Collins 2016, pp. 193–195.

- Collins 2016, pp. 40–41.

- Sinisi 2020, p. 113.

- Collins 2016, p. 197.

- Collins 2016, p. 91.

- Sinisi 2020, pp. 160–164.

- Collins 2016, pp. 31, 66.

- Collins 2016, p. 67.

- Langsdorf 1964, pp. 288–289.

- Langsdorf 1964, p. 288.

- Collins 2016, pp. 70–71.

- Kirkman 2011, p. 83.

- Collins 2016, p. 72.

- Collins 2016, pp. 73–75.

- Collins 2016, pp. 77, 79.

- Sinisi 2020, pp. 188–189.

- Kennedy 1998, p. 383.

- Collins 2016, pp. 86, 90.

- Sinisi 2020, pp. 208–209.

- Collins 2016, p. 90.

- Sinisi 2020, p. 209.

- Lause 2016, p. 94.

- Monnett 1995, p. 86.

- Sinisi 2020, pp. 209–210.

- Sinisi 2020, p. 210.

- Sinisi 2020, pp. 210–211.

- Sinisi 2020, pp. 211–212.

- Kirkman 2011, p. 98.

- Monnett 1995, p. 87.

- Lause 2016, pp. 95–96.

- Sinisi 2020, p. 212.

- Lause 2016, p. 96.

- Sinisi 2020, pp. 212–213.

- Monnett 1995, p. 88.

- Sinisi 2020, pp. 213–214.

- Sinisi 2020, p. 214.

- Sinisi 2020, pp. 214–215.

- Sinisi 2020, p. 215.

- Lause 2016, p. 97.

- Sinisi 2020, p. 216.

- Kirkman 2011, p. 101.

- Collins 2016, pp. 91, 114 n. 41.

- Collins 2016, pp. 92–93.

- Kennedy 1998, pp. 383–386.

- American Battlefield Protection Program 2011, p. 9.

- American Battlefield Protection Program 2011, p. 21.

- American Battlefield Protection Program 2011, p. 26.

- "Second Battle of Independence Self-Guided Tour". Missouri Department of Tourism. Retrieved April 5, 2021.

- "Civil War Sites of Independence Self-Guided Tour". Civil War Roundtable of Western Missouri. August 13, 2011. Retrieved July 3, 2021.

Sources

- Collins, Charles D. Jr. (2016). Battlefield Atlas of Price's Missouri Expedition of 1864 (PDF). Fort Leavenworth, Kansas: Combat Studies Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-940804-27-9.

- Kennedy, Frances H., ed. (1998). The Civil War Battlefield Guide (2nd ed.). Boston & New York: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-74012-5.

- Kirkman, Paul (2011). The Battle of Westport: Missouri's Great Confederate Raid. Charleston, South Carolina: The History Press. ISBN 978-1-60949-006-5.

- Langsdorf, Edgar (1964). "Price's Raid and the Battle of Mine Creek" (PDF). The Kansas Historical Quarterly. Topeka, Kansas: Kansas State Historical Society. 30 (3). ISSN 0022-8621.

- Lause, Mark A. (2016). The Collapse of Price's Raid: The Beginning of the End in Civil War Missouri. Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press. ISBN 978-0-826-22025-7.

- Monnett, Howard N. (1995) [1964]. Action Before Westport 1864 (Revised ed.). Boulder, Colorado: University Press of Colorado. ISBN 978-0-87081-413-6.

- Parrish, William Earl (2001) [1973]. A History of Missouri: 1860–1875. Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press. ISBN 978-0-8262-1376-1.

- Sinisi, Kyle S. (2020) [2015]. The Last Hurrah: Sterling Price's Missouri Expedition of 1864 (paperback ed.). Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-5381-4151-9.

- "Update to the Civil War Sites Advisory Commission Report on the Nation's Civil War Battlefields: State of Missouri" (PDF). Washington, D.C.: American Battlefield Protection Program. March 2011.