Battle of Inkerman

The Battle of Inkerman was fought during the Crimean War on 5 November 1854 between the allied armies of Britain and France against the Imperial Russian Army. The battle broke the will of the Russian Army to defeat the allies in the field, and was followed by the Siege of Sevastopol. The role of troops fighting mostly on their own initiative due to the foggy conditions during the battle has earned the engagement the name "The Soldier's Battle."[2]

| Battle of Inkermann | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Crimean War | |||||||

The 20th Foot at the Battle of Inkerman David Rowlands | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

FitzRoy Somerset François Canrobert | Alexander Menshikov | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 15,700 | 40,500 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 4,676 killed & wounded[1] | 11,959 killed & wounded[1] | ||||||

Prelude to the battle

The allied armies of Britain, France, Sardinia, and the Ottoman Empire had landed on the west coast of Crimea on 14 September 1854, intending to capture the Russian naval base at Sevastopol.[3] The allied armies fought off and defeated the Russian Army at the Battle of Alma, forcing them to retreat in some confusion toward the River Kacha.[4] While the allies could have taken this opportunity to attack Sevastopol before Sevastopol could be put into a proper state of defence, the allied commanders, British general FitzRoy Somerset, 1st Baron Raglan and the French commander François Certain Canrobert could not agree on a plan of attack.[5]

Instead, they resolved to march around the city, and put Sevastopol under siege. Toward this end the allies marched to the southern coast of the Crimean peninsula and established a supply port at the city of Balaclava.[6] However, before the siege of Sevastopol began, the Russian commander Prince Menshikov evacuated Sevastopol with the major portion of his field army, leaving only a garrison to defend the city.[7] On 25 October 1854, a superior Russian force attacked the British base at Balaclava, and although the Russian attack was foiled before it could reach the base, the Russians were left holding a strong position north of the British line. Balaclava revealed the allied weakness; their siege lines were so long they did not have sufficient troops to man them. Realising this, Menshikov launched an attack across the Tchernaya River on 4 November 1854.[8]

Battle

Assault

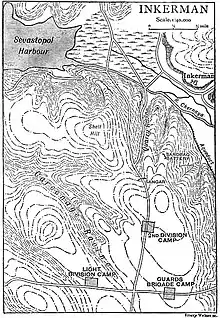

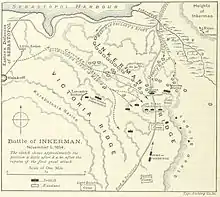

On 5 November 1854, the Russian 10th Division, under Lt. General F. I. Soymonov, launched a heavy attack on the allied right flank atop Home Hill east from the Russian position on Shell Hill.[9] The assault was made by two columns of 35,000 men and 134 field artillery guns[10] of the Russian 10th Division. When combined with other Russian forces in the area, the Russian attacking force would form a formidable army of some 42,000 men. The initial Russian assault was to be received by the British Second Division dug in on Home Hill with only 2,700 men and 12 guns. Both Russian columns moved in a flanking fashion east towards the British. They hoped to overwhelm this portion of the Allied army before reinforcements could arrive. The fog of the early morning hours aided the Russians by hiding their approach.[8] Not all the Russian troops could fit on the narrow 300-meter-wide heights of Shell Hill.[10] Accordingly, General Soymonov had followed Prince Alexander Menshikov's directive and deployed some of his force around the Careenage Ravine. Furthermore, on the night before the attack, Soymonov was ordered by General Peter A. Dannenberg to send part of his force north and east to the Inkerman Bridge to cover the crossing of Russian troop reinforcements under Lt. General P. Ya. Pavlov.[10] Thus, Soymonov could not effectively employ all of his troops in the attack.

When dawn broke, Soymonov attacked the British positions on Home Hill with 6,300 men from the Kolyvansky, Ekaterinburg and Tomsky regiments.[11] Soymonov also had a further 9,000 in reserve. The British had strong pickets and had ample warning of the Russian attack despite the early morning fog. The pickets, some of them at company strength, engaged the Russians as they moved to attack. The firing in the valley also gave warning to the rest of the Second Division, who rushed to their defensive positions. De Lacy Evans, commander of the British Second Division, had been injured in a fall from his horse so command of the Second Division was taken up by Major-General John Pennefather, a highly aggressive officer. Pennefather did not know that he was facing a superior Russian force. Thus he abandoned Evans' plan of falling back to draw the Russians within range of the British field artillery which was hidden behind Home Hill.[11] Instead, Pennefather ordered his 2,700 strong division to attack. When they did so, the Second Division faced some 15,300 Russian soldiers. Russian guns bombarded Home Hill, but there were no troops on the crest at this point.

The Second Division in action; the Russians in the valley

The Russian infantry, advancing through the fog, were met by the advancing Second Division, who opened fire with their Pattern 1851 Enfield rifles, whereas the Russians were still armed with smoothbore muskets.[12] The Russians were forced into a bottleneck owing to the shape of the valley, and came out on the Second Division's left flank. The Minié balls of the British rifles proved deadly accurate against the Russian attack.[13] Those Russian troops that survived were pushed back at bayonet point. Eventually, the Russian infantry were pushed all the way back to their own artillery positions. The Russians launched a second attack, also on the Second Division's left flank, but this time in much larger numbers and led by Soymonov himself. Captain Hugh Rowlands, in charge of the British pickets, reported that the Russians charged "with the most fiendish yells you can imagine."[11] At this point, after the second attack, the British position was incredibly weak. If Soymonov had known the condition of the British, he would have ordered a third attack before the British reinforcements arrived.[13] Such a third attack might well have succeeded, but Soymonov could not see in the fog and thus did not know of the desperate situation of the British. Instead, he awaited the arrival of his own reinforcements—General Pavlov's men who were making their way toward the Inkerman battlefield in four different prong attacks from the north.[lower-alpha 1] However, the British reinforcements arrived in the form of the Light Division which came up and immediately launched a counterattack along the left flank of the Russian front, forcing the Russians back. During this fighting Soymonov was killed by a British rifleman.[13] Russian command was immediately taken up by Colonel Pristovoitov, who was himself shot a few minutes later. Colonel Uvazhnov-Aleksandrov assumed command of the Russian forces but was also killed in the withering British fire. At this point, no officer seemed keen to take up command and Captain Andrianov was sent off on his horse to consult with various generals about the problem.[13]

The rest of the Russian column proceeded down to the valley where they were attacked by British artillery and pickets, eventually being driven off. The resistance of the British troops here had blunted all of the initial Russian attacks. General Paulov, leading the Russian second column of some 15,000, attacked the British positions on Sandbag Battery. As they approached, the 300 British defenders vaulted the wall and charged with the bayonet, driving off the leading Russian battalions. Five Russian battalions were assailed in the flanks by the British 41st Regiment, who drove them back to the River Chernaya.

Home Hill

General Peter A Dannenberg took command of the Russian Army, and together with the uncommitted 9,000 men from the initial attacks, launched an assault on the British positions on Home Hill, held by the Second Division. The Guards Brigade of the First Division (The Highland Brigade was guarding Balaclava), and the Fourth Division were already marching to support the Second Division, but the British troops holding the Barrier withdrew, before it was re-taken by men from the 21st, 63rd Regiments and The Rifle Brigade. This position remained in British hands for the rest of the battle, despite determined attempts to take it back. The Russians launched 7,000 men against the Sandbag Battery, which was defended by 2,000 British soldiers. So began a ferocious struggle which saw the battery change hands repeatedly. The division commander Prince George, Duke of Cambridge, had a horse shot under him, and he found himself with around 100 men, the rest pushing down the slope. He was nearly cut off by another advancing Russian column, but he and his aide managed to get back.

Meanwhile, the Light Division occupied Victoria Ridge throughout the day. Its commander, Sir George Brown (British Army officer) was wounded, so General William Codrington (British Army officer) took command. He refused the help of other troops, perpetually sending them back to the battle.

Fourth Division in action

When the British Fourth Division arrived under General George Cathcart, they were finally able to go on the offensive, but confusion reigned. The Duke requested him to fill the 'gap' on the left of the Guards, to prevent them from being isolated; when Cathcart asked Pennefather where to help, Pennefather replied "Everywhere.", so Cathcart dispersed his men in different directions, until about 400 men were left. Quartermaster general Richard Airey (1st Baron Airey) told to "Support the Brigade of Guards. Do not descend or leave the plateau... Those are Lord Raglan's orders." Cathcart moved his men to the right. The courage of Cathcart and his men had the unexpected effect of encouraging other British units to charge the Russians. However, the flanking troops were caught in the rear by an unexpected Russian counter-attack, during which Cathcart, believing that the Guards had mistaken them for Russians, ordered his men to remove their greatcoats, but the firing intensified, and Cathcart was shot from his horse and killed as he led 50 men of the 20th Regiment of Foot up a hill, leaving his troops disorganized and the attack was broken up. This gave the Russian army an opportunity to gain a crest on the ridge. However, as the Russian troops were coming up, they were attacked and driven off by newly arrived soldiers from the French camps. The French, with marvelous rapidity, brought up a division from five miles away and poured reinforcements into the entire line, reducing the Russians' advantage in numbers.[15]

Defence of Home Hill by the British and French forces

At this point in the battle the Russians launched another assault on the Second Division's positions on Home Hill, but the timely arrival of the French Army under Pierre Bosquet and further reinforcements from the British Army repelled the Russian attacks. The Russians had now committed all of their troops and had no fresh reserves with which to act. Two British 18-pounder guns along with field artillery bombarded the 100-gun strong Russian positions on Shell Hill in counter-battery fire. With their batteries on Shell Hill taking withering fire from the British guns, their attacks rebuffed at all points, and lacking fresh infantry, the Russians began to withdraw. The allies made no attempt to pursue them. Following the battle, the allied regiments stood down and returned to their siege positions.

Aftermath

Despite being severely outnumbered, the allied troops held their ground in a marvelous display of discipline and tenacity. The amount of fog during the battle led to many of the troops on both sides being cut off, in battalion-sized groups or less. Thus, the battle became known as "The Soldier's Battle". The Russian attack, although unsuccessful, had denied the allies any attempt at gaining a quick victory in the siege of Sevastopol. Following this battle, the Russians made no further large-scale attempts to defeat the allies in the field.

Alexander Kinglake obtained the official casualty returns for the battle. By his account allied casualties were: 2,573 British, of whom 635 were killed, and 1,800 French, of whom 175 were killed. Russia lost 3,286 killed within a total (including men taken prisoner) of 11,959 casualties.[lower-alpha 2]

Legacy

_-_Russell-98466_-_On_the_field_of_Inkerman.jpg.webp)

The battle popularised the use of the name Inkerman in placenames in Victorian England, including Inkerman Road in Kentish Town, London; Inkerman Road, St Albans, and Inkerman Way in Knaphill. There is an Inkerman Street in St Kilda, Victoria, Australia, in between Balaclava Rd and Alma Rd. Inkerman, a locality in South Australia, was named in 1856. There is also an Inkerman, New Brunswick named after the battle.

On Operation Herrick in Afghanistan, there was a Forward Operating Base called FOB Inkerman.

The third company of the Grenadier Guards is known colloquially as the “Inkermann Company” for their part in the battle.

See also

Notes

- See the map on page XXX of Orlando Figes, The Crimean War.[14]

- From the general engagement of the 5th November, including the fight on Mount Inkerman, there resulted, it seems, to the Russians a loss of 9,845 in killed, wounded, and prisoners [of which 3,286 killed]; to the English a loss of 2,573, of whom 635 were killed...Official return[s].[16]

Citations

- Norman (1911).

- Mackenzie (2021).

- Figes (2010), p. 203.

- Figes (2010), pp. 215–216.

- Figes (2010), p. 222.

- Figes (2010), p. 225.

- Figes (2010), p. 241.

- Figes (2010), p. 258.

- Figes (2010), pp. 257–259.

- Figes (2010), p. 257.

- Figes (2010), p. 259.

- Myatt (1979), p. 50.

- Figes (2010), p. 260.

- Figes (2010), p. XXX.

- Porter (1889), p. 433.

- Kinglake (1863), p. 458.

References

- Figes, Orlando (2010). The Crimean War: A History. New York: Picador Publishing.

- Kinglake, A.W. (1863). Invasion of the Crimea, Volume 5. Edinburgh: Blackwood.

- Mackenzie, John. "Battle of Inkerman". BritishBattles.com. John Mackenzie. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- Myatt, F. (1979). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of 19th Century Firearms. New York: Salamander Books.

- Norman, C. B. (1911). Battle Honours of the British Army. London: John Murray. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- Porter, Maj Gen Whitworth (1889). History of the Corps of Royal Engineers Vol I. Chatham: The Institution of Royal Engineers.

External links

- Report in the Times of 1 Feb 1875

- Report in the Times of 4 Feb 1875

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 14 (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 573–574.