Battle of Pochonbo

The Battle of Pochonbo (Japanese: 普天堡の戦い, Hepburn: Futenho no tatakai) was an event which occurred in northern Korea on 4 June 1937 (Juche 26), when Korean and Chinese guerrillas commanded by Kim Il Sung (or possibly Choe Hyon)[3][4] attacked and defeated a Japanese detachment during the anti-Japanese armed struggle in Korea. The battle holds an important place in North Korean narratives of history.[5]

| Battle of Pochonbo | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Japanese colonial rule over Korea | |||||||

The battle depicted in the Grand Monument in Samjiyon, Samjiyon County | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Northeast Anti-Japanese United Army |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Kim Il Sung | Unknown | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Sixth Division of the Second Army of the First Route Army[1] | Unknown | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 150–200[2] | 33 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 20 killed | 9 killed | ||||||

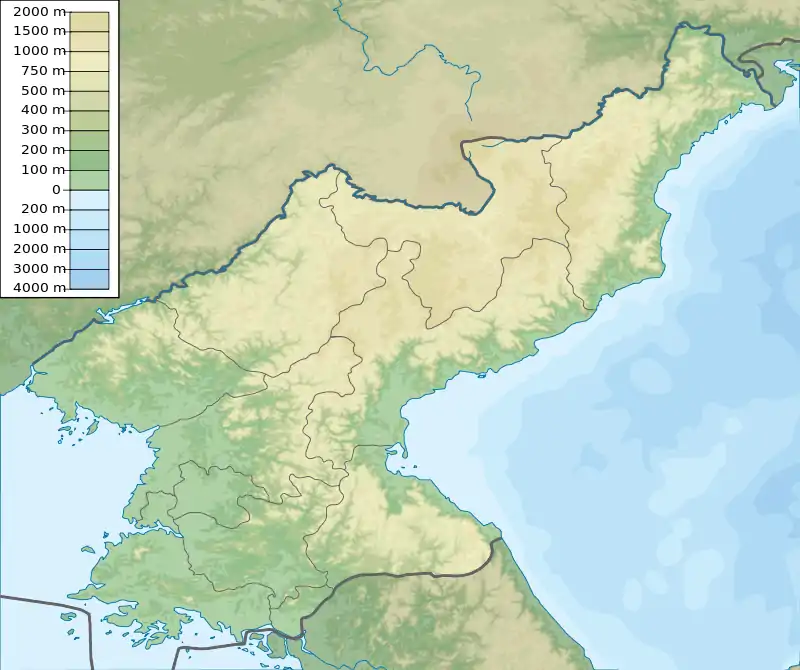

Location within North Korea | |||||||

Battle

According to the Korean Friendship Association, the battle was in retaliation to the brutality of the Japanese occupation of Korea at a time when "the Japanese imperialists perpetrated unheard-of fascist tyranny against the Korean people".[6]

According to the official North Korean version of the events, a small unit of about 150–200 guerrillas of the Northeast Anti-Japanese United Army's Sixth Division[2] under Kim Il Sung crossed the Amnok River and arrived at the Konjang Hill on 3 June 1937. At 22:00, Kim Il Sung fired a shot into the sky, and the battle started. During the battle, the Japanese-occupied police station, post office, foresters' office, local elementary school, fire department hall were destroyed by the guerrillas.[1][2][6] Kim took 4,000 yen from local people and inflicted damage estimated at 16,000 yen. He took the town but only occupied it for a few hours or a day before retreating to Manchuria.[1][2]

Following combat, Kim Il Sung made a speech, where he noted that the Korean people "turn out as one in the sacred anti-Japanese war".[6] The battle is featured in Kim Il Sung's autobiography With the Century. In it, too, Kim describes his guerrilla troops acting spontaneously and motivated by emotion rather than reason and strategic insights.[5] In it, he said of the event:

The Battle of Pochonbo showed that imperialist Japan could be smashed and burnt up, like rubbish. The flames over the night sky of Pochonbo in the fatherland heralded the dawn of the liberation of Korea, which had been buried in darkness. The Pochonbo Battle was a historic battle which not only showed to the Korean people who thought Korea to be dead that Korea is not dead but alive, but also gave them the confidence that when they fight, they can achieve national independence and liberation.

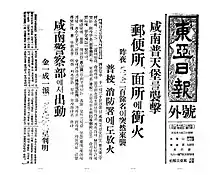

This official version of the battle does not correspond with some contemporary records such as a Japanese newspaper, however, which suggest that the rebels were actually led by Choe Hyon.[3]

Aftermath and legacy

The news of the battle was reported in numerous newspapers across the world, including the Soviet Union, China, Japan and France.[8] According to the Association for the Study of Songun Politics UK, a pro-North Korean Juche study group:

Another historic significance of the Battle of Pochonbo was that it demonstrated at home and abroad a sure will of the Korean revolutionaries, who pioneered the revolution with arms and would advance it by dint of arms. The battle was an ordinary raid, which combined the use of small arms and a speech designed to stir up public feeling. However, that small battle made a great impact on the world because it showed the truth that the armed imperialists and colonialists should only be fought with arms to emerge victorious in the revolution for national liberation.[9]

The event brought Kim some fame among both his comrades as well as the Japanese. As a result, his influence grew, though the Japanese Imperial Army also started to hunt him, and almost wiped out his force. He was eventually forced retreat into the Soviet Union in 1940.[2] Northern Korea was officially liberated from Japan on V-J Day (15 August 1945). Kim subsequently returned to his home country, and when he managed to establish himself with Soviet help as head of People's Committee of North Korea and Party's north faction (predecessors of future North Korea and WPK, respectively), his reputation as hero of Pochonbo helped him to gain acceptance and support among the people.[10]

Kim Il-sung's legitimacy came from propaganda that he fought against Japan, symbolised by the Battle of Pochonbo ... Schools in North Korea teach children that the battle was a glorious victory against Japan led by Kim Il-sung.

Ken Kato, a researcher and human rights activist[3]

Since then, the North Korean government has continuously reinforced the importance of the Battle of Pochonbo and Kim Il Sung's role in it. As result, it was speculated that Kim Jong Un, Kim Il Sung's grandson, had purged Choe Hyon's son Choe Ryong-hae in 2014 to prevent the undermining of the official version of the battle.[3] It later became clear, however, that Choe Ryong-hae had not been purged at all and remained an influential member of the North Korean government.[11][12]

The battle first entered the history textbook of South Korea in 2003, account Kim Il Sung's efforts on Anti-Japanese in relatively circumspect narratives. Controversies were raised on whether it makes students idolize North Korean regimes, or it could become a sign of South Korean history education stepping out from the cold-war thinking.[13]

The Pochonbo Electronic Ensemble takes its name from the battle.

Battle site

The battle site is situated at Pochon County, Ryanggang Province at the Kusi Barrage on Kojang Hill.[14]

Monument

Samjiyon Grand Monument complex (area 100,000 m2) was completed in 1979 and includes a 15m-high statue of a Kim Il-sung, a huge square for rallies and many sculptures. This place was chosen as it is said to be where the guerrillas rested before the raid.[15]

- Samjiyon Grand Monument complex

See also

References

- Kim Il Sung: The North Korean Leader page 34

- Schönherr 2012, p. 27.

- Ryall, Julian. "Rival to Kim's regime among 200 on verge of being purged". telegraph.co.uk. The Telegraph. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- Ryall, Julian (3 April 2014). "Son of North Korean 'hero' who was written out of history feared to be latest target of Kim Jong-un's purges". news.nationalpost.com. Associated Press. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

One article in the Asahi Shimbun, a Japanese newspaper, dated June 7, 1937, three days after the skirmish, says: "A little more than 100 men led by communist bandit Choe Hyon attacked Pochonbo."

- Silberstein, Benjamin (10 May 2016). "Warfare by Feelings: Strategy, Spontaneity, and Emotions in Kim Il-sung's Tactical Thinking". Sino-NK. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- "The Battle of Pochonbo". kfausa.org. The Korean Friendship Association. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- Kim, Il-Sung. "With the Century" (PDF). korea-dpr.com. The Korean Friendship Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 July 2011. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- "Anniversary of Victorious Pochonbo Battle Marked". kcna.co.jp. Archived from the original on 11 October 2014. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- "Flames of Pochonbo". uk-songun.com. Association for the Study of Songun Politics UK. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- Schönherr 2012, p. 28.

- Choe Sang-hun (9 May 2016). "North Korea Expels BBC Journalists Over Coverage". New York Times. Retrieved 9 May 2016.

- "Choe Ryong-hae elected to N.K. ruling party's central military commission". Yonhap. 8 October 2017.

- "Making History, South Korea Gives Archenemy a Little Credit". The New York Times. 2003-01-26.

- "Pochonbo Revolutionary Battle Site". kcna.co.jp. Korean Central News Agency. Archived from the original on 12 October 2014. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- "Samjiyon Grand Monument | North Korea Travel Guide - Koryo Tours". koryogroup.com. 2020-04-29. Retrieved 2023-07-14.

Works cited

- Schönherr, Johannes (2012). North Korean Cinema: A History. London: Mcfarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-6526-2.

External links

Media related to Pochonbo Incident at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Pochonbo Incident at Wikimedia Commons