Battle of Warsaw (1705)

The Battle of Warsaw (also known as the Battle of Rakowitz or Rakowiec)[Note 1] was fought on 31 July 1705 (Gregorian calendar)[Note 2] near Warsaw, Poland, during the Great Northern War. The battle was part of a power struggle for the Polish–Lithuanian throne. It was fought between Augustus II the Strong and Stanisław Leszczyński and their allies. Augustus II entered the Northern war as elector of Saxony and king of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, and had formed an alliance with Denmark–Norway and Russia. Stanisław Leszczyński had seized the Polish throne in 1704, with the support of the Swedish army of Charles XII of Sweden. The struggle for the throne forced the Polish nobility to pick sides; the Warsaw Confederation supported Leszczyński and Sweden, and the Sandomierz Confederation supported Augustus II and his allies. The conflict resulted in the Polish civil war of 1704–1706.

| Battle of Warsaw | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Great Northern War | |||||||

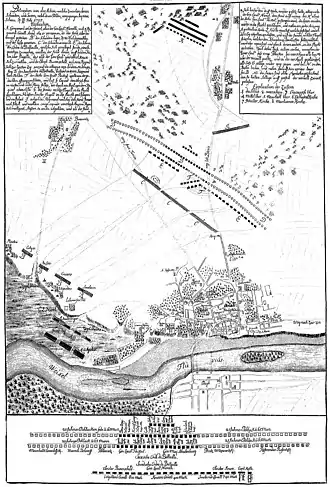

Anonymous plate of the battle of Warsaw | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

2,000:[1] 60 infantry |

9,500:[1] 3,500 Saxon cavalry | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

144 killed, 148 wounded[2] | 1,000 killed, wounded and captured[2] | ||||||

In 1705 two events were planned to take place in Warsaw: a session of the Polish parliament to formally negotiate peace between Poland and Sweden; and the coronation of Stanisław Leszczyński as the new Polish king. Meanwhile, Augustus II and his allies developed a grand strategy that envisioned a combined assault to crush the Swedish forces and restore Augustus II to the Polish throne. Accordingly, an allied army of up to 10,000 cavalry under the command of Otto Arnold von Paykull was sent towards Warsaw to interrupt the Polish parliament. The Swedes sent a 2,000-strong cavalry contingent of their own, under the command of Carl Nieroth, to protect it. Encouraged by the fact that he heavily outnumbered the Swedes, Paykull took the initiative and attacked. He managed to cross the Vistula River with his army on 30 July, after a stubborn defence by a few Swedish squadrons, and reached the plains next to Rakowiec, directly west of Warsaw, on 31 July, where the two forces engaged in an open battle.

Augustus II's allied left wing quickly collapsed; after a short but fierce fight, so did the right and centre. Paykull managed to rally some of his troops a few kilometres away, at the village of Odolany, where the fight was renewed. The Swedes again gained the upper hand and, this time, won the battle. They captured Paykull along with letters and other documents which informed the Swedes of the strategic intentions of Augustus II's allies. The coronation of Stanisław Leszczyński occurred in early October. Peace between Poland and Sweden in November 1705 allowed the Swedish king to focus his attention on the Russian threat near Grodno. The subsequent campaign resulted in the Treaty of Altranstädt (1706), by which Augustus II renounced both his claim to the Polish throne and his alliance with Peter I of Russia.

Background

.jpg.webp)

After defeating the Danes at Humlebæk and the Russians at Narva in 1700, Charles XII of Sweden turned his attention towards his third enemy, Augustus II of Poland and Saxony, defeating him in a fierce battle at the Crossing of the Düna in 1701.[3] The same year, he launched an invasion of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth to dethrone Augustus II and install a candidate acceptable to Sweden. After the Swedes' seizure of Warsaw, Kraków and Sandomierz[4] and another defeat for Augustus II at the Battle of Kliszów, a growing number of Polish-Lithuanian magnates switched sides, in favour of Charles XII.[5]

After further success in the engagements at Pultusk and Toruń, the Swedes proclaimed Stanisław Leszczyński king with the support of the Warsaw Confederation of Polish nobles. To oppose him, the Sandomierz Confederation was created by other nobles, in support of Augustus II, thus starting the Polish civil war of 1704–1706.[4] Some smaller engagements at Poznań, Lwów, Warsaw and Poniec followed in 1704 as a consequence of Augustus II's attempts to restore the situation to his favour.[6]

In 1705 Stanisław Leszczyński was due to be crowned in Warsaw, after which peace negotiations between Sweden and Poland could take place. The Swedes were eager to increase support for Leszczyński to strengthen their position in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. The coalition forces, under Peter I of Russia and Augustus II, would not sit idle, and planned a grand strategy of their own, mainly based upon the ideas of Johann Patkul and Otto Arnold von Paykull; they would gather all available forces and crush the Swedish Army in Poland–Lithuania by a joint offensive.[4]

Prelude

The Swedes reconquered Kraków in early 1705, with 4,000 men under Swedish lieutenant Nils Stromberg, forcing between 3,000[7] and 4,000[8] Saxons to evacuate the city and retreat towards Lublin. This led the nobles of Kraków and Sandomierz to renounce their support for Augustus II in favour of Stanisław Leszczyński; they started to gather in Warsaw for the session of parliament. Further support from the Ruthenian Voivodeship (duchy) appeared from Lviv,[7] along with Józef Potocki and his 7,000 troops.[9] These movements were observed by the Saxons, who withdrew from the left bank of the Vistula River completely, along with all Polish troops, and marched towards Brest to better coordinate with the Russian army in Lithuania. This meant the coronation of Stanisław Leszczyński in Warsaw as well as negotiations for peace between Poland and Sweden could safely go ahead. The parliamentary session was scheduled to start on 11 July.[7]

Receiving news of this event, Charles XII of Sweden, headquartered in Rawicz at the time, sent a contingent of troops from Gniezno on 6 July[Note 3] consisting of 2,000 cavalry under Carl Nieroth to protect Warsaw.[10] Another 2,000 infantry[7] under Johan Valentin von Daldorff of the Dala and Uppland Regiments were also ordered to depart on 29 July from Kaliszkowice Ołobockie[Note 4] as reinforcements, and to form an escort for Stanisław Leszczyński; but they would not arrive at the Polish capital until 11 August, more than a week after the battle.[11]

Nieroth arrived at Warsaw just before 11 July and opened the parliamentary session according to schedule.[12] He established camp just south of the city next to the Vistula River.[13] Meanwhile, the Saxons who had been forced out of Kraków and back to Brest departed for Warsaw in early July. They united banners with between 5,000[14] and 6,000 Poles and Lithuanians,[15] led by Stanisław Chomętowski and Janusz Antoni Wiśniowiecki. The overall command of the force was assigned to Otto Arnold von Paykull whose orders from Augustus II were to disrupt the parliamentary session. Paykull's vanguard, under the command of Adam Śmigielski, soon arrived in the vicinity of Praga, on the opposite side of the Vistula from Warsaw, and attempted to cross the river on several occasions.[8]

Initial skirmishes

On 16 July, some 1,000 Poles crossed the river at Karczew[8] and attacked a Swedish guard-post consisting of 20 men. After defending themselves for some time, the Swedes were reinforced by 150 cavalrymen who forced the Poles to retire, leaving behind 30 dead. A further 200 men drowned as they went back over the Vistula River and four men ended up in captivity. Five days later, the Polish commander Stanisław Chomętowski arrived at Praga with 67 banners of Polish–Lithuanian cavalry and 400 Saxons. He attempted to cross the Vistula to Warsaw in boats and ferries. He was repulsed, but the repeated attempts caused the nobility in Warsaw to scatter.[16] Paykull appeared with his full army by the end of the month and immediately overwhelmed two small Swedish reconnaissance units sent by Nieroth to operate on that side of the river.[17] Here some important intelligence was gained, informing Paykull of the exact strength of the enemy, hardly 2,000 men, as well as the condition of the river.[18]

Paykull held a council of war, and planned a joint strike on Nieroth's vulnerable cavalry before the arrival of further Swedish reinforcements.[19] Nieroth, being informed of their intentions on 28 July, split off two small units, with 186 men in each, under the commands of Jon Stålhammar and Claes Bonde, to scout for the enemy in the vicinity of the Vistula river.[20][Note 5] As the river proved to be shallower than usual for July, the Swedish command had trouble predicting where Paykull could and would commit.[21]

The scouting party under Stålhammar was ordered to search 30 km (19 mi) south-southeast towards Góra Kalwaria while Bonde scouted as far as Kazuń Nowy, 40 km (25 mi) north-west of Warsaw. Thus more than 70 kilometres of the Vistula River were patrolled.[13] On 29 July, Paykull committed to an attack with his Saxons, Poles and Lithuanians.[18] He intended to cross the river some 30 km (19 mi) north-west of Warsaw, near Zakroczym, which Bonde received intelligence of during the night of 29–30 July, while in Kazuń Nowy.[13] With a mere 26 men[17][Note 6] he rapidly marched to investigate before the arrival of his remaining 160 troops.[13]

He arrived there in the morning and soon found the vanguard of Paykull's army, consisting of 500 men who had just completed the crossing in advance of the bulk of their army.[22] Despite being massively outnumbered, Bonde followed his instructions to prevent any attempt made by the coalition to cross the river. Almost immediately the small party attacked their enemies, but after a desperate fight, they were cut down to the last man. The remaining 160 Swedes arrived at the scene, followed the example of their leader, and attacked. By this time about half of the coalition forces, approximately 5,000 men, were across. The Swedes were encircled,[23] and after a sharp battle, repulsed, with a loss of about 100 men killed or captured.[20][Note 7] Only one of the initial three squadrons of some 80 men managed to retreat back to Warsaw and notify Nieroth of the action.[17]

The seemingly foolish act at the beaches near Zakroczym caused the coalition troops under Paykull to suffer some lost momentum which allowed Nieroth more time to organise his troops for the forthcoming battle. The Polish military commander Stanisław Poniatowski, a supporter of Stanisław Leszczyński, wrote afterwards: "The bravery and fearlessness which the Swedish officer [Bonde] had displayed, caused some terror to be struck into our enemies".[23] Von Paykull remained confident, and sent a courier to Augustus II, informing him that the Swedes were on the run and the parliament in Warsaw scattered. He added, "I hope to deliver the furious and wild Swedish lad to your Majesty within 14 days, dead or alive".[17]

Battle

When Nieroth was informed of Paykull's crossing on the afternoon of 30 July,[17] he decided he was not properly equipped to withstand a siege.[1] Instead he marched his army past Warsaw to about 5 km (3 mi) north-west of the city to receive the coalition forces there, in an open battle. As it was already far into the evening by the time he arrived, and with no sign of the enemy, he chose to go back and position his troops between Warsaw and Rakowiec, just west of the initial Swedish camp.[17] At sunrise, around 04:00 in the morning, on 31 July, he received intelligence that Paykull was marching towards him along the road from Błonie, west of Warsaw. Soon afterwards, Nieroth drew his army up in battle order and marched towards Wola to face the advancing enemy.[24]

Swedish forces

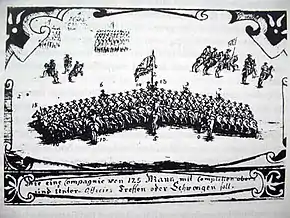

The Swedish force under the command of Nieroth consisted of between 1,800[25] and 2,000 men in three regiments, divided into 24 squadrons (eight squadrons in each regiment) with one company of infantry.[26] The Swedish regiments were positioned, from left to right: 800 men from the Östergötland Cavalry Regiment; 400 men from the Upplands tremännings Cavalry Regiment (also known as Kruse's Cavalry Regiment); and 740 men from the Småland Cavalry Regiment[24] under the commands of Jacob Burensköld, Carl Nieroth and Carl Gustaf Kruse, respectively.[27] A company of 60[Note 8] infantry from the Skaraborg Infantry Regiment under captain Sven Kafle had also arrived the day before[28] and took position on the far right.[16]

Allied forces

The Saxons and Polish–Lithuanians were between 8,000[29] and 10,000 men strong under the overall command of Otto Arnold von Paykull. The Saxons were positioned in the centre with the Lithuanians to their left and the Poles to their right.[24] The Saxon force included some 3,500 men[1][Note 9] in 12 different regiments, totaling 43 squadrons.[27]

The first Saxon line, under the personal command of Paykull with the generals Daniel Schulenburg and Saint Paul assisting, included, in order from left to right:[24] the Life Guard (Leib) Dragoon Regiment;[30] the Milkau Dragoon Regiment;[30] the Gersdorff Cuirassier Regiment;[30] the Steinau Cuirassier Regiment;[30] and the Life Guard (Leib) Cuirassier Regiment.[30] Each regiment had 250 men divided into three squadrons.[31] Furthest to the right was the Garde du Corps Cavalry Regiment[30] with 500 men in four squadrons.[31]

The second Saxon line included, in order from left to right: the Schulenburg Dragoon Regiment;[30] the Goltz Dragoon Regiment;[30] the Flemming's Cuirassiers;[31][Note 10] the Crown Prince (Kurprinz) Cuirassier Regiment;[30] the Queen's (Königin) Cuirassier Regiment;[30] and the Brause Dragoon Regiment,[30] each with 240 men in three squadrons.[31]

The Saxon reserve line consisted of a group of handpicked cuirassiers to the left, with 200 men in three squadrons,[31] and the Eichstadt Cuirassier Regiment[30] to the right, with 225 men[Note 11] in three squadrons.[24]

The Poles and Lithuanians fielded between 5,000[14] and 6,000 men.[1] The Poles, with around 2,600 men, were positioned on the right wing with 40 banners (each banner was about 65 men) and were commanded by Stanisław Chomętowski, Stanisław Ernest Denhoff and Felicjan Czermiński.[24] The Lithuanians on the left wing consisted of some 2,300[14] to 3,300 men[24] in 35[14] to 50 banners (each banner with about 65 men), and were commanded by Stanisław Mateusz Rzewuski and Janusz Antoni Wiśniowiecki.[24]

Rakowiec

Both armies had some difficulties as they marched towards each other, as high grain covered much of the field.[1] Furthermore, the unusually hot and dry summer contributed to large dust clouds being raised, which were swept by strong westerly winds to obscure vision. The Swedes in particular struggled, with the wind in their faces.[24] After they had marched 2.5 km (2 mi), the armies sighted each other and advanced to battle. Both armies soon confirmed the great disparity in numbers between them. The Saxon and Polish–Lithuanian force (even with two lines, three men deep, and a reserve line behind) was double the width of the Swedish force (with one line, no more than two men deep, and no reserve).[32]

Paykull took advantage of the situation and quickly ordered his wings to stretch out further before impact, in an attempt to completely encircle the Swedes. The commanders of each Swedish regiment drew further out to the sides themselves, to somewhat match the width of their opponents lines. This action caused the Swedish line to split in two and left an opening in the centre between the Östgöta and Uppland regiments. Soon afterwards the general of the Östgöta Regiment on the left wing, Burensköld, sent Nieroth an urgent plea for reinforcements,[32] as his regiment alone was about to face more than half, around 5,000, of the enemy force.[33] Nieroth, who was with the Uppland and Småland regiments further to the right, and heavily outnumbered himself, had no choice but to decline the request.[32]

At around 08:00 in the morning, just north of the village of Rakowiec, west of Warsaw, the two sides collided.[1] After enduring a volley from their enemies the Swedes charged, sword in hand, along the whole front in their typical Carolean formations.[33] As the Swedes charged, Paykull, who had acknowledged the split in the Swedish centre, quickly ordered six squadrons of the Life Guard Dragoons, Milkau Dragoons and Gersdorff Cuirassiers to exploit the opening. They struck the Uppland Regiment in their left flank, as they were committing to the frontal assault. This caused confusion among the four squadrons furthest to the left of the regiment, which fell into disorder and lost three standards.[34]

Simultaneously, the Saxon squadrons furthest to the left, along with the Lithuanian cavalry, almost immediately collapsed and routed at the impact of the charge. They were briskly pursued by the Småland Regiment and the other half of the Uppland Regiment, under Nieroth, which had not been hit in the flank.[35] Some Lithuanians at the end of the wing, whose banners extended further than the width of the Swedish line, had initially proceeded with the flanking manoeuvre; they were soon driven off as some squadrons of the Småland Regiment turned their attention towards them,[34] pursuing and harassing them for 20 km (12 mi) in a northerly direction.[33]

As the Uppland and Småland regiments collided with their enemies on the Swedish right wing, the left wing under Burensköld and his Östgöta Regiment simultaneously charged home into the Saxons opposing them. After a short but fierce fight, the first Saxon line was forced to quit, dragging the second line with them in the retreat.[26] The Poles, being furthest out on the wing where the Swedish line did not extend, had managed to partially encircle the Swedes, and started to attack their flank and rear as they pursued the Saxons. This gave the Saxons enough breathing room to rally some of their troops and counterattack. The Swedish Östgöta Regiment was then forced to split their squadrons in two by leaving a few to halt the Poles in the rear, the others facing the counter-attacking Saxons to their front.[34]

The four Swedish squadrons of the Uppland Regiment under Carl Philip Sack had during this time managed to rally their banners and in turn push back the six Saxon squadrons which had hit them in the flank in the early stage of the engagement. They then rushed to the aid of the vulnerable Östgöta Regiment along with the Skaraborg Regiment under Sven Kafle, causing the Poles and Saxons to retreat once more, unable to handle the pressure. This would end the fighting near Rakowiec.[36]

Odolany

As the Swedes of the Östgöta Regiment reached the village of Wola in their pursuit of the Saxons, they discovered that Paykull had reorganised his forces at the nearby village of Odolany. Some time was spent resting the exhausted horses and regrouping the available squadrons before recommencing the attack. Soon the other four squadrons of the Uppland Regiment arrived,[37] although very depleted after the fighting at Rakowiec.[26]

Paykull had positioned his Saxon troops very advantageously, with the left flank protected by a hedge towards Odolany, and on the right a large force of Poles,[26] with two hidden Saxon squadrons of the Garde du Corps, ready to fall upon the rear of the Swedes.[37] All his Saxon squadrons were present, except the six he had committed to attack the centre of the Swedish army in the previous fight.[38] He was further encouraged by the fact that his troops outnumbered the Swedes four to one, even without reckoning the Poles on the right. So he envisioned that he would be able to crush the few Swedes in front of him and then turn against the rest of the Swedish force, who were for the time being occupied with chasing the Lithuanians.[26]

Having disposed his troops, with the Uppland Regiment on the left, Burensköld commenced his attack. As the Swedes charged forward, the two hidden Saxon squadrons fell onto the rear of their left flank, causing some disorder.[39] The Saxon left wing, where Paykull remained, collapsed even before impact, and ran.[26] Two Swedish squadrons were then sent to assist in the ongoing fight, as the rest pursued the fleeing enemy. Order was restored on the left wing after some fierce fighting, when the 60 infantrymen from the Skaraborg Regiment arrived in time to give a strong volley from their muskets to end the struggle.[39]

Paykull was captured as the Swedes pursued the fleeing enemy for about 5 km (3 mi).[39] He had fallen into a ditch and was about to be killed by two Swedish cavalrymen before a third, Magnus Rydberg, intervened.[40] The Swedes under Burensköld called off the pursuit, being unaware of the course of the rest of the battle, and returned towards Warsaw.[39]

End of the battle

The Swedes started to move their forces towards Warsaw in the afternoon, after having pursued their enemies for many kilometres in different directions. Some Poles, who had crossed the Vistula from Praga during the battle to loot, were chased back over the river by the Småland Regiment, where 300[41] to 500 of them drowned. The battle had lasted for six hours, from 8:00 in the morning to 2:00 in the afternoon.[42]

123 Saxons and 17 Poles had been captured, including Paykull.[31] Some 300[39] to 500 Saxons had been killed and almost as many Poles and Lithuanians.[18] In total, they had suffered between 1,000[2] and 2,000 men dead, wounded and captured in the battle.[43] The Swedes had sustained 144 men killed, 143 wounded and five men captured.[44][Note 12] Many horses were also lost. In just the Östgöta Regiment, 178 horses were dead and 70 wounded. After the battle the regiment could field only about 550 men, down from 800; the rest were dead, wounded, without horses or scattered.[45]

It is clear that Paykull had not received orders from Augustus II encouraging him to give battle to the Swedes; he was only to interrupt the coronation of Stanisław Leszczyński. In this he initially succeeded, as many of the noblemen in Warsaw fled at his presence by the Vistula River, and would have remained scattered as long as he posed a threat with his army. Historians have concluded that the size of his army, at least 8,000 men,[46] compared with the smaller Swedish force that was awaiting reinforcements,[19] made him eager to seek battle with them while they were heavily outnumbered.[46]

Aftermath

The scattered Polish noblemen, receiving notice of the victory, eventually returned and proceeded with the coronation of Stanisław Leszczyński and the declaration of peace between Sweden and Poland.[47] Meanwhile, Augustus II's allies obtained reinforcements of about 1,000 Russians and once again threatened to disrupt the parliament, until the two Swedish infantry regiments under Johan Valentin von Daldorff finally arrived,[48] on 11 August,[11] with Stanisław Leszczyński and the Swedish ambassadors.[48] This put a temporary end to the ambitions of Augustus II's allies, forcing them to withdraw towards Lithuania and unite with the Russian Army stationed there.[47]

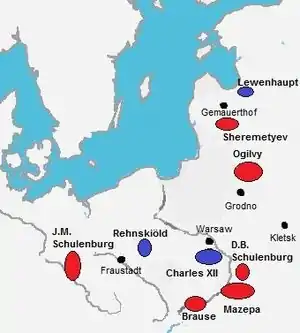

The main Swedish army at Rawicz,[Note 13] under Charles XII, struck camp at 8 August and marched towards Krotoszyn, where the captured Otto Arnold von Paykull was taken under strict military surveillance, for an audience with the king.[49] Some letters and documents Paykull had carried with him during the battle, which he had tried to discard before his imminent capture, had been brought with him to Krotoszyn.[40] The documents informed Charles XII of the greater allied plan, under which the Tsar, Peter I of Russia, intended to march into Warsaw on 30 August at the head of 40,000 men and put an end to the parliament.[50] This would, they thought, provoke Charles XII to take action and march with the Swedish army to Warsaw, where he would find himself surrounded by Johann Matthias von der Schulenburg[51] and his 20,000 men, who were assembling in Saxony,[52] to move into Poland and attack the Swedes in the rear. Charles XII, who had long sought a decisive battle with the coalition forces, indicated no sign of panic at this, but simply stated to his ministers: "I wish the enemy may keep their word". On 10 August, he once again struck camp and commenced a rapid march with his army towards Błonie, close to Warsaw, arriving on 17 August.[51] He had left General Carl Gustaf Rehnskiöld with 10,000 men near Poznań to guard against the main Saxon army under Schulenburg which threatened to enter Poland.[53]

The Russian Tsar abandoned his plans after seeing how two of his and Augustus II's armies had already suffered defeat at the hands of the Swedes: the one under Boris Sheremetev that faced Adam Ludwig Lewenhaupt in Courland, during the Battle of Gemauerthof, and now at the Battle of Warsaw, between Paykull and Nieroth. As he no longer dared to fully commit in Poland,[54] he decided to instead let his main army under Georg Benedict Ogilvy await the Swedes behind the strongly fortified defences of Grodno, in Lithuania. He would attempt to lure Charles XII there, while the Saxon army under Schulenburg would enter Poland from the west, and attack him in the rear. These developments would result in the Campaign of Grodno.[55]

Outcome

Stanisław Leszczyński's coronation, as Stanisław I of Poland, was completed on 4 October, with no further interference from Augustus II's allies.[56] After some smaller skirmishes outside, or near, Warsaw, among them an attempt made to destroy the recently Swedish-constructed bridge connecting Warsaw and Praga,[57] peace between Sweden and Poland was finally established on 28 November.[58] These developments allowed Charles XII to break camp on 9 January 1706 with his 20,000 men, and march towards the Russians at Grodno, where he partly encircled the city and starved them out.[59] Meanwhile, the Saxon army under Schulenburg was defeated by Rehnskiöld at the Battle of Fraustadt. This would result in a Swedish invasion of Saxony and the Treaty of Altranstädt (1706), by which Augustus II renounced all his claims to the Polish throne.[60]

Paykull, the captured allied general, had been born in Swedish Livonia, and was legally considered a Swedish subject; he was thus considered a traitor to the nation for having taken up arms against it. He was shipped to Sweden and put on trial in Stockholm, sentenced to death by decapitation, and executed on 14 February 1707.[61]

See also

Sources

Notes

- Rakowiec later became part of the Ochota district of Warsaw.

- Unless otherwise stated, this article uses dates from the Gregorian calendar (new style), in preference to the Swedish or the Julian calendar (old style) which were used simultaneously.

- The date when the Östergötland Cavalry Regiment departed.(Stenhammar 1918, pp. 70–72)

- The date and place from where the Dalarna Regiment departed.(Philström 1902, p. 147)

- Numbers vary from 180 (Stenhammar 1918, p. 70) to 200.(Sjögren & Hildebrand 1881, p. 145)

- Other sources say 20 (Stenhammar 1918, p. 70) and even 10.(Phillips 1705, p. 332)

- Other sources say 90 killed.(Stenhammar 1918, p. 71)

- Other sources say 90.(Sjögren & Hildebrand 1881, p. 147)

- The Saxon force is usually estimated to have been between 3,000 (Imhof & Schönleben 1719, p. 101) and 4,000 men.(Stenhammar 1918, p. 72)

- Flemming's Dragoons, according to Kling and Sjöström.(Kling & Sjöström 2015, p. 210)

- 250 according to L. Visocki-Hochmuth.(Visocki-Hochmuths & Quennerstedt 1901, p. 209)

- Or 124 killed and a little over 129 wounded,(Adlerfelt 1740, pp. 148–149) or 156 killed or missing and 148 wounded.(Nordberg 1745, p. 428)

- The army at Rawicz numbered only 6,000 men at the time, as other regiments were dispersed elsewhere.(Svensson 2001, p. 84) As the army struck camp at Błonie, on 9 January 1706, the number had increased to 20,000 men, as most of the forces had then arrived.(Sjöström 2009, pp. 86–87)

Footnotes

- Kling & Sjöström 2015, p. 200.

- Phillips 1705, p. 298.

- Dorrell 2009, pp. 11–12.

- Kling & Sjöström 2015, pp. 198–199.

- Dorrell 2009, p. 15.

- Sundberg 2010, pp. 226–227.

- Svensson 2001, p. 83.

- Sjögren & Hildebrand 1881, p. 144.

- Sjöström 2009, p. 60.

- Stenhammar 1918, pp. 70–72.

- Philström 1902, p. 147.

- Nordberg 1745, p. 424.

- Stenhammar 1918, p. 70.

- Imhof & Schönleben 1719, p. 212.

- Adlerfelt 1740, p. 144.

- Nordberg 1745, p. 425.

- Sjögren & Hildebrand 1881, p. 145.

- Phillips 1705, p. 334.

- Adlerfelt 1740, pp. 144–145.

- Phillips 1705, p. 332.

- Grimberg & Uddgren 1914, p. 228.

- Grimberg & Uddgren 1914, p. 229.

- Stenhammar 1918, p. 71.

- Stenhammar 1918, p. 72.

- Stålhammar & Quennerstedt 1912, p. 101.

- Phillips 1705, p. 335.

- Adlerfelt 1740, p. 146.

- Grimberg & Uddgren 1914, p. 230.

- Imhof & Schönleben 1719, p. 213.

- Kling & Sjöström 2015, p. 210.

- Visocki-Hochmuths & Quennerstedt 1901, p. 209.

- Stenhammar 1918, pp. 72–73.

- Grimberg & Uddgren 1914, p. 231.

- Sjögren & Hildebrand 1881, p. 146.

- Adlerfelt 1740, p. 147.

- Adlerfelt 1740, pp. 147–148.

- Grimberg & Uddgren 1914, p. 232.

- Phillips 1705, p. 336.

- Stenhammar 1918, p. 74.

- Sjögren & Hildebrand 1881, p. 147.

- Stålhammar & Quennerstedt 1912, p. 102.

- Nordberg 1745, p. 428.

- Fryxell 1868, p. 327.

- Visocki-Hochmuths & Quennerstedt 1901, p. 210.

- Stenhammar 1918, pp. 75–76.

- Imhof & Schönleben 1719, pp. 212–213.

- Adlerfelt 1740, p. 149.

- Nordberg 1745, p. 429.

- Sjögren & Hildebrand 1881, pp. 147–148.

- Sjögren & Hildebrand 1881, p. 148.

- Adlerfelt 1740, p. 151.

- Kling & Sjöström 2015, p. 199.

- Sjöström 2009, p. 75.

- Fant 1804, p. 52.

- Sjöström 2009, pp. 70–72.

- Sjöström 2009, p. 84.

- Grimberg & Uddgren 1914, pp. 233–236.

- Sjöström 2009, p. 85.

- Sjöström 2009, pp. 86–87.

- Sjöström 2009, p. 280.

- Sjögren & Hildebrand 1881, pp. 148–156.

Bibliography

- Adlerfelt, Gustavus (1740), The Military History of Charles XII, King of Sweden, Volume 2, London: J. and P. Knapton, OCLC 15007018

- Dorrell, Nicholas (2009), The Dawn of the Tsarist Empire: Poltava & the Russian Campaigns of 1708–1709, Leigh-on-Sea: Partizan Press, ISBN 978-1-85818-594-1

- Fant, Eric Michael (1804), Utkast til föreläsningar öfver svenska historien, Volume 5 (in Swedish), Stockholm: H. A. Nordström, OCLC 465751042

- Fryxell, Anders (1868), Berättelser ur Svenska Historien, Volume 21 (andra upplagan) (in Swedish), Stockholm: L. J. Hiertas Förlag, OCLC 985122698

- Grimberg, Carl; Uddgren, Hugo (1914), Svenska krigarbragder (in Swedish), Stockholm: Norstedts Förlag, OCLC 458438026

- Imhof, Andreas Lazarus von; Schönleben, Conrad (1719), Neu-eröffneter Historischer Bilder-Saal. Volume 7 (in German), Nuremberg: Felsecker, OCLC 165780196

- Kling, Steve; Sjöström, Oskar (2015), Great Northern War Compendium (Volume One), St. Louis: THGC Publishing, ISBN 978-0-9964557-0-1

- Nordberg, Jöran Andersson (1745), Ett kort dock tydeligit utdrag utur then öfwer konung Carl den Tolftes lefwerne och konglida dater (in Swedish), Stockholm: P.J. Nyström, OCLC 42798853

- Phillips, John (1705), The Present State of Europe, or, The Historical and Political Mercury, Volume 16, London: Randal Taylor, 1690-, OCLC 79556490

- Philström, Anton (1902), Kungl. Dalregementets Historia III (in Swedish), Stockholm: P. A. Norstedt & Söner, OCLC 928729340

- Sjögren, Otto; Hildebrand, Emil (1881), Historisk Tidskrift, Första Årgången: Otto Arnold Paykull (in Swedish), Stockholm: Svenska Historiska Föreningen, OCLC 457966837

- Sjöström, Oskar (2009), Fraustadt 1706, ett fält färgat rött (in Swedish), Lund: Historiska Media, ISBN 978-91-85507-90-0

- Stålhammar, Jon; Quennerstedt, August (1912), Karolinska Krigares Dagböcker, VII (in Swedish), Lund: Glreerupska univ. Bokhandeln, OCLC 186563524

- Stenhammar, Waldemar (1918), Östgöta Kavalleriregemente i Karl XII:s Krig (in Swedish), Linköping: Östgöta Correspondentens Boktryckeri, OCLC 801814346

- Sundberg, Ulf (2010), Sveriges krig, Del 3: 1630–1814 (in Swedish), Stockholm: Svenskt Militärhistoriskt Biblioteks Förlag, ISBN 978-91-85789-63-4

- Svensson, Axel (2001), Karl XII som fältherre (in Swedish), Stockholm: Svenskt Militärhistoriskt Bibliotek, ISBN 978-91-974056-1-4

- Visocki-Hochmuths, L.; Quennerstedt, August (1901), Karolinska Krigares Dagböcker, II (in German), Lund: Glreerupska univ. Bokhandeln, OCLC 245712146