Battle of Roatán

The Battle of Roatán (sometimes spelled "Rattan") was an American War of Independence battle fought on March 16, 1782, between British and Spanish forces for control of Roatán, an island off the Caribbean coast of present-day Honduras.

| Battle of Roatán | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Revolutionary War | |||||||

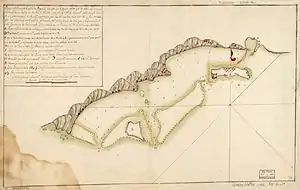

A 1782 Spanish map of Roatán. New Port Royal is visible on the right side of the island. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Edward Marcus Despard[1] |

Matías de Gálvez Gabriel Herbias Enrique MacDonell | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 81+ regulars |

600 regulars 3 frigates | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

2 wounded 81 captured |

2 killed 4 wounded | ||||||

A Spanish expeditionary force under Matías de Gálvez, the Captain General of Spanish Guatemala, gained control of the British-held island after bombarding its main defences. The British garrison surrendered the next day. The Spanish evacuated the captured soldiers, 135 civilians and 300 slaves, and destroyed their settlement, which they claimed had been used as a base for piracy and privateering.

The assault was part of a larger plan by Gálvez to eliminate British influence in Central America. Although he met with temporary successes, the British were able to maintain a colonial presence in the area.

Background

Following the entry of Spain into the American War of Independence in 1779, both Spain and Great Britain contested territories in Central America. Although most of the territory was claimed to be part of the Spanish Captaincy General of Guatemala, the British had established logging rights on the southern coast of the Yucatan Peninsula (present-day Belize), and had established settlements on the Mosquito Coast. Guatemalan Governor Matías de Gálvez had moved quickly when the declaration of war arrived, seizing St. George's Caye, one of the principal British island settlements off the Yucatan coast.[2]

Many of the British fled that occupation to the island of Roatán, another British-controlled island about 40 miles (64 km) off the Honduran coast.[3] British commander Edward Marcus Despard used Roatán as a base for guerilla-style operations to extend and maintain British influence on the Mosquito Coast, and for privateering operations against Spanish shipping.[4] (Sources do not indicate whether Despard was present on Roatán at the time of the Spanish attack; if he was, he was probably not captured, since he continued to be active in the area. Stephens suggests that he was on Jamaica at the time.)[1][5]

Gálvez, who had been ordered by King Charles to "dislocate the English from their hidden settlements on the Gulf of Honduras,"[6] began planning offensive operations against the British mainland settlements as early as 1780, after the British abandoned their failed expedition into Nicaragua. He raised as many as 15,000 militia, and received financial and logistical support from many parts of the Spanish colonial empire in the Americas. For logistical and diplomatic reasons, no operations were launched until after the American victory at Yorktown in October 1781.

The British loss opened the possibility that the British would be able to deploy troops to Central America to better defend the area.[7] Gálvez's plans called for assaults on the British presence in the Bay Islands (principally Roatán), followed by a sweep along the coast to eliminate the British from the mainland. Troops from central Guatemala were staged in early 1782 at Trujillo for the assault on Roatán, while additional forces moved overland from Nicaragua, Honduras, and Salvador toward the principal British settlement of Black River.[8]

Gálvez arrived at Trujillo on March 8 to organise the assault on Roatán. Leaving a force of 600 at Trujillo to further harass the British and their partisan allies, he embarked another 600 troops onto transports, and sailed for Roatán on March 12, escorted by three frigates (the Santa Matilde, Santa Cecilia, and Antiope) and a number of smaller armed naval vessels,[9] under the command of Commodore Enrique MacDonell.[10]

The British residents of Roatán were aware of the ongoing Spanish military activities. The main settlement, New Port Royal, was defended by Forts Dalling and Despard, which mounted 20 guns. The island's white non-slave population was, however, quite small. In 1781 they appealed to the British commander at Bluefields for support, but he was only able to send additional weapons, which did not add significantly to the island's defenses.[11]

Battle

The Spanish fleet arrived off Roatán at 6:00 am on March 13, and after its defenders fired several ineffectual cannon shots, the Santa Matilde and the other ships anchored out of range. At 8 am Gálvez sent in his English-speaking second-in-command on the Santa Matilde, Enrique MacDonell, to request the surrender of the island's defenders. The defenders asked for six hours to consider their options, which Gálvez granted. After that time had elapsed, MacDonell came back with word that the defenders refused to surrender and were prepared to stand their ground "to the death." The Spanish were not surprised, as their sailors had noticed the English appeared to be preparing defenses during grace period. An immediate attack was not possible due to high winds and rough seas, so Gálvez then held council of his 11 officers, and a plan of attack was formulated.[12]

At about 10:15 am on March 16, Spanish guns opened up against Forts Dalling and Despard, which guarded the mouth of New Port Royal's harbour. By 1:00 pm the British guns there had been silenced, and Major General Gabriel Herbias began landing troops. After the two forts were secured, the Spanish warships entered the harbour and began raking the town with cannon fire, while British artillery fired back from positions in the hills above the town. This exchange continued until sunset, at which time the British defenders capitulated.[12] The Spanish had two killed and four wounded in the battle, while only two slaves were wounded on the other side.[11]

Aftermath

Terms of surrender were agreed the next day. Gálvez and his men remained on the island for several days collecting weapons, rounding up slaves that had run away, destroying all the buildings and agriculture on the island, and burning many of the ships in the harbour, which they assumed to be used in smuggling and other illicit trade.[12] The Spanish left the island on March 23, carrying as prisoners of war 81 British soldiers, 300 slaves, and 135 British civilians.[13] The prisoners were sent to Havana, where the slaves were auctioned off and the others held until they could be exchanged.[11]

Gálvez was able to only temporarily partially eliminate British influences in the area. He followed up his success at Roatán with the capture of Black River in early April, but any attempt to advance further lost momentum. James Lawrie, the commander at Black River, and Edward Marcus Despard successfully recaptured Black River, and were able to hold it until the end of the war.[14]

See also

References

- Stephens, p. 254

- Chávez, p. 152

- Bolland, p. 31

- Oman, p. 5

- Oman, p. 6

- Chávez, p. 151

- Floyd, pp. 154–155

- Floyd, p. 155

- Chávez, pp. 162–163

- Marley, p. 342

- Floyd, p. 157

- Chávez, p. 163

- Chávez, p. 164

- Chávez, p. 165

- Bolland, O. Nigel (2003). Colonialism and Resistance in Belize: Essays in Historical Sociology. Benque Viejo del Carmen, Belize: Cubola Productions. ISBN 978-968-6233-04-9. OCLC 149133872.

- Chávez, Thomas E (2004). Spain and the Independence of the United States: An Intrinsic Gift. UNM Press. ISBN 978-0-8263-2794-9. OCLC 149117944.

- Floyd, Troy (1967). The Anglo-Spanish Struggle for Mosquitia. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press. OCLC 13392015.

- Marley, David (1998). Wars of the Americas: a Chronology of Armed Conflict in the New World, 1492 to the Present. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-87436-837-6.

- Oman, Charles (1922). The Unfortunate Colonel Despard. New York: B. Franklin. OCLC 1173611.

- Stephens, Alexander (1804). Public Characters, Volume 4. Printed for R. Phillips, by T. Gillet. OCLC 1929272.