Battle of Tlatelolco

The Battle of Tlatelolco was fought between the two pre-Hispanic altepetls (or city-states) Tenochtitlan and Tlatelolco, two independent polities which inhabited the island of Lake Texcoco in the Basin of Mexico.

| Battle of Tlatelolco | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

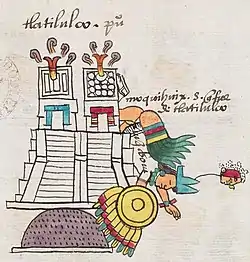

The burning temple of Tlateloclo and the death of Moquihuixtli, as depicted in the Codex Mendoza (early 16th century). | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Tlatelolco | Aztec Empire | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Moquihuixtli † | Axayacatl | ||||||

The war was fought between Moquihuix (or Moquihuixtli), the tlatoani (ruler) of Tlatelolco, and Axayacatl, the tlatoani of Tenochtitlan. It was a last-ditch attempt by Moquihuix and his allies to challenge the might of the Tenochca, who had recently cemented their political dominance within the empire.[1] Ultimately the rebellion failed, resulting in the death of Moquihuix who is pictured in the Codex Mendoza tumbling down the Great Temple of Tlatelolca.[2] As a result of the battle, Tlatelolco was subsumed by Tenochtitlan, removed of its privilege and required to pay tribute to Tenochtitlan every eighty days.[3]

Origin

Axayacatl ascended the Mexica throne following the death of his maternal grandfather Motecuhzoma Illhuicamina in 1469.[2] Moctezuma had spent his long reign leading Tenochtitlan to primacy over the Valley of Mexico. As a result, Emily Umberger argues, fellow rulers were "predisposed to challenge" the new tlatoani in an attempt "to restore the importance of their own cities".[1] One of these challengers was Moquihuix, Axayacatl's brother-in-law, who was married to his older sister Chalchiuhnenetzin. While we do not know the exact date of his ascendance to the Tlatelolco throne, Moquihuix seemingly spent some time rebuilding the key religious structures in his city prior to the war.[4] Umberger has argued that these new buildings were constructed as "close imitations of those in Tenochtitlan, built to irritate and mock the Tenochca".[1]

According to Dominican friar Diego Durán in his History of the Indies of New Spain, trouble first began to brew between the two provinces in the fifth year of Axayacatl's reign following an attack on the daughters of the lords of Tlatelolco by the sons of Tenochca noblemen in the Tlatelolco marketplace. At the same time, while the Tlatelolcas were digging a canal to allow passageway into the city, a Tlatelolca built canal was “found broken up and filled in". Both these acts greatly angered the lords of Tlatelolco. Durán claims that, as a result of these actions, the Tlatelolcas declared themselves independent to Tenochtitlan decrying: "O Aztecs, we who live in Tlatelolco, take courage, let us destroy the Tenochcas". With the encouragement of a fellow nobleman, Teconal, Moquihuix summoned all young men over the age of twenty to participate in a series of war exercises aimed to prepare the Tlatelolca to be called to arms at any moment.[5]

The Battle in the Sources

There are a variety of different accounts of the Battle of Tlatelolco in the sources.

Diego Durán

Durán gives an expansive account of the war, depicting it to have taken place in two distinct battles. The first was a Tlatelolca attack on Tenochtitlan. The initial plan was to attack Tenochtitlan at night, killing Axayacatl's older confidants first to leave the young tlatoani defenceless. However, this plan quickly got out and was spread to Axayacatl following a heated exchange between women from both sides in the Tlatelolca marketplace. Having also been informed of Moquihuix’s war games, Axayacatl decided to place guards secretly throughout the city to spy. He too ordered that all men should be made ready for battle.

Meanwhile, Moquihuix, who had been spooked by a series of seemingly evil omens, decided to consult the gods, making celebration in their honour. The celebrations turned sour, however, when the Tlatelolcas began to sing a number of war songs, belittling the people of Tenochtitlan. Durán notes that when they wanted to sing "the Tenochcas" they sang the "Tlatelolcas".[3] Fearful that such omens would temper the rebellion, Teconal encouraged Moquihuix to attack that night: "everything is ready. Whenever you desire we shall go kill those wildcats who are our neighbours".[3] Moquihuix thus sent out his spies to Tenochtitlan who found Axayacatl playing ball with his noblemen. This was done intentionally, however, Axayacatl had been prior warned of the plan by his sister, and Moquihuix's wife, Chalchiuhnenetzin. The spies returned to Tlatelolco, informing Moquihuix that the Tenochcas were ignorant to any plan.

As a result, the first battle commenced with Moquihuix readying his troops, entrusting Teconal the stratagem for the attack. Half of the men were sent to hide in the city limits of Tenochtitlan in preparation for an ambush. The other half were sent to cover the walls of Tenochtitlan and block any escape routes. At midnight the signal was given and the Tlatelolca warriors emerged, shouting and yelling. However, the Tenochca were prepared and soon managed to surround them. The resultant onslaught was great, with men on both sides massacred. The Tlatelolcas were humiliated by their defeat and requested that they should be able to fight the Tenochca openly on the battlefield. All Tlatelolcan men were readied for battle.

Axayacatl called his councillors to decide what to do. They wished to avoid any more bloodshed. It was agreed that they would try and calm Moquihuix and his advisor’s ire through reason. A messenger, Cueyatzin, was sent to Tlatelolco. Moquihuix responded with repugnance: "tell your lord the king that the answer is that he should be prepared because the people of Tlatelolco are determined to avenge the deaths of the other night".[3] Upon hearing this message, Tlacael decried Moquihuix's arrogance, calling for Cueyatzin to return to Tlatelolco, "taking with him the ointments and insignia that are applied to the dead".[3] Cueyatzin did this immediately, presenting Moquihuix with the funerary insignia. Teconal then appeared and swiftly beheaded Cueyatzin whose head was carried back to the boundaries of Tenochtitlan and thrown. Greatly angered by this action, Axayacatl emerged, armed, and led his Tenochca army towards the city's border where the Tlatelolcas waited, ready for war. Here, then, the second battle commenced. The Tenochcas proved deadly, pushing the Tlatelolcas backwards into the marketplace. Seeing that the battle was lost, Moquihuix and Teconal began to ascend the steps of the central temple-pyramid in order to distract the others so that the army could regroup. According to Durán, this distraction consisted of a squadron of naked women "slapping their bellies" and "squirting milk at the soldiers".[3] These women were accompanied by a group of young boys, also naked, and wailing. The Tenochcas, dismayed by the crudity, were ordered not to harm the women nor boys but rather take them prisoner - which they did successfully. Cecilia Klein has looked at this account in the context of the way gender was understood within Aztec warfare. Here she contends that these women were fighting using the "signs of their gender" and links them to the "Women of Discord".[6][7]

Axayacatl proceeded to climb the Tlatelolco pyramid. When he arrived at the summit he found Moquihuix and Teconal clinging to the altar of Huitzilopochtli. Axayacatl slew both men and dragged their bodies out, casting them down the steps of the temple. When the Tlatelolcas saw their chieftain killed, they fled the marketplace and hid in the canals, among the reeds and rushes. However, they were pursued relentlessly by the Tenochca. The war only ceased when Axayacatl's aged uncle, Cuacuauhtzin, beseeched his nephew to give the orders to end the slaughter. Axayacatl stated that since the Tlatelolco had rebelled against the royal crown, from this point on they would have to pay tribute and that all liberties and exemptions enjoyed by Tlatelolco would henceforth cease. When these conditions had been met, he reasoned, the Tlatelolco would be pardoned.

The Codex Mendoza

The Codex Mendoza's account of the war is considerably briefer. In it Moquihuix is described as "a powerful and haughty man' who 'began to pick quarrels and fights" with the Tenochca.[2] Following the resultant "great battles" it is said that Moquihuix, "pressed in battle", fled and took refuge in a temple.[2] However, upon being rebuked by one of the temple's priests for his cowardice, he flung himself off the high temple and died.[2] Tenochtitlan thus emerged victorious and, from this point on, Tlatelolco paid its tribute and acknowledged its vassalage to Tenochtitlan.

Codex Chimalpahin

The Codex Chimalpahin again tells an alternative version of the battle. Here the onus is placed on Moquihuix's relationship with his wife, Chalchiuhnenetzin. According to the Codex Chimalpahin, Chalchiuhnenetzin, the elder sister of Axayacatl, was "despised" and maltreated by her husband who preferred the company of his "concubines".[8] Chalchiuhnenetzin was said to have journeyed to Tenochtitlan to speak to her brother and tell him of her mistreatment, she also informed him of the fact that Moquihuix was "talking of making war on the lord of Tenochtitlan".[8] According to Chimalpahin, it was as a result of this that the war between the two polities began.

Chimalpahin states that the war continued for a year with it only coming to an end upon the death of Moquihuix. It is said that the Tenochca "threw [Moquihuix] from the top of an earthen mound along with his hunchbacks and [a] quetzal feather crest, there ending the rulership in Tlatelolco".[8]

Legacy

Matthew Restall, along with others, has seen that, despite being subsumed by Tenochtitlan in 1473, Tlatelolco continued to have some semblance of a separate identity following the war, with the people usually referring to themselves as Tlatelolca rather than Mexicana. We see the result of this, Restall argues, in Sahagún's Florentine Codex, which was written in partnership with his former students from the Colegio de Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco, through the scapegoating of Moctezuma II whom the Tlatelolca blamed for the Mexica-Tenochca defeat.[9] Inga Clendinnen has seen this amalgamated within the "returning god-ruler theory", the idea that Moctezuma was "paralyzed by terror [...] by the conviction that Cortés was Quetzalcoatl".[10]

References

- Umberger, Emily (2007). "The Metaphorical Underpinnings of Aztec History". Ancient Mesoamerica. 18 (1): 11–29. doi:10.1017/s0956536107000016. ISSN 0956-5361. S2CID 162571940.

- The essential Codex Mendoza. Berdan, Frances F., Anawalt, Patricia Rieff, 1924-. Berkeley: University of California Press. 1997. ISBN 0520204549. OCLC 34669354.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Durán, Diego, -1588. (1994). The history of the Indies of New Spain. Heyden, Doris. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0585125112. OCLC 44954467.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Anales de Tlatelolco. Tena, Rafael. (1. ed. en Cien de México ed.). México, D.F.: CONACULTA. 2004. ISBN 9703505074. OCLC 61484747.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Aztec imperial strategies. Berdan, Frances F. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection. 1996. pp. 96–7. ISBN 0884022110. OCLC 27035231.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Klein, Cecelia F. (1994). "Fighting with femininity gender and war in Aztec Mexico" (PDF). Estudios de Cultura Náhuatl. 24: 221–53.

- PENNOCK, CAROLINE DODDS (2018-02-20). "Women of Discord: Female Power in Aztec Thought". The Historical Journal. 61 (2): 275–299. doi:10.1017/s0018246x17000474. ISSN 0018-246X.

- Chimalpahin Cuauhtlehuanitzin, Domingo Francisco de San Antón Muñón, 1579-1660. (1997). Codex Chimalpahin : society and politics in Mexico Tenochtitlan, Tlatelolco, Texcoco, Culhuacan, and other Nahua altepetl in central Mexico : the Nahuatl and Spanish annals and accounts collected and recorded by don Domingo de San Antón Muñón Chimalpahin Quauhtlehuanitzin. Anderson, Arthur J. O., Schroeder, Susan., Ruwet, Wayne. Norman, Okla.: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0806129212. OCLC 36017075.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Restall, Matthew (2003). Seven Myths of the Spanish Conquest. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Clendinnen, Inga. (2010). The cost of courage in Aztec society : essays on Mesoamerican society and culture. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139775786. OCLC 817224463.