Battle of Wake Island

The Battle of Wake Island was a battle of the Pacific campaign of World War II, fought on Wake Island. The assault began simultaneously with the attack on Pearl Harbor naval and air bases in Hawaii on the morning of 8 December 1941 (7 December in Hawaii), and ended on 23 December, with the surrender of American forces to the Empire of Japan. It was fought on and around the atoll formed by Wake Island and its minor islets of Peale and Wilkes Islands by the air, land, and naval forces of the Japanese Empire against those of the United States, with Marines playing a prominent role on both sides.

| Battle of Wake Island | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Pacific Theater of World War II | |||||||

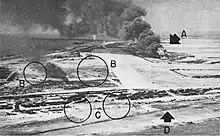

A destroyed Japanese patrol boat (#33) on Wake. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

First Attempt (11 December): 3 light cruisers 6 destroyers 2 patrol boats 2 troop transports 1 submarine tender 3 submarines Reinforcements arriving for Second Attempt (23 December): 2 aircraft carriers 2 heavy cruisers 2 destroyers 2,500 infantry[1] |

449 USMC personnel consisting of:

12 aircraft 12 anti-aircraft guns 68 U.S. Navy personnel 5 U.S. Army personnel | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

First attempt: 2 destroyers sunk 340 killed 65 wounded 2 missing[2] 1 submarine sunk Second attempt: 2 patrol boats wrecked 10 aircraft lost 21 aircraft destroyed 600 casualties[3] |

52 killed 49 wounded 2 missing 12 aircraft lost[4] 1 scow sunk[5] 433 captured[6] | ||||||

|

70 civilians killed 1,104 civilians interned, of whom 180 died in captivity[7] | |||||||

Location within Pacific Ocean | |||||||

The island was held by the Japanese for the duration of the Pacific War theater of World War II; the remaining Japanese garrison on the island surrendered to a detachment of United States Marines on 4 September 1945, after the earlier surrender on 2 September 1945 on the battleship USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay to General Douglas MacArthur.[8]

Prelude

In January 1941, the United States Navy constructed a military base on the atoll. On 19 August, the first permanent military garrison, elements of the 1st Marine Defense Battalion[9] deployed to Wake Island under the command of Major P.S. Devereux, USMC with a force of 450 officers and men. Despite the relatively small size of the atoll, the Marines could not man all their defensive positions nor did they arrive with all their equipment, notably their air search radar units.[10] The Marine Detachment was supplemented by Marine Corps Fighter Squadron VMF-211, consisting of 12 F4F-3 Wildcat fighters, commanded by Marine aviator Major Paul A. Putnam, USMC. Also, present on the island were 68 U.S. Navy personnel and about 1,221 civilian workers for the Morrison-Knudsen Civil Engineering Company. The workers were to carry out the company's construction plans for the island. Most of these men were veterans of previous construction programs for the Boulder Dam, Bonneville Dam, or Grand Coulee Dam projects. Others were men who were in desperate situations and great need for money.[11] Forty-five Chamorro men (native Micronesians from the Mariana Islands and Guam) were employed by Pan American Airways at the company's facilities on Wake Island, one of the stops on the Pan Am Clipper trans-Pacific amphibious air service initiated in 1935.

The Marines were armed with six 5-inch (127 mm)/51 cal pieces, originating from the old battleship USS Texas (1892); twelve 3 in (76 mm)/50 cal anti-aircraft guns (with only a single working anti-aircraft director among them); eighteen .50 in (12.7 mm) Browning heavy machine guns; and thirty .30 in (7.62 mm) heavy, medium and light water- and air-cooled machine guns.

On 28 November, naval aviator Commander Winfield S. Cunningham, USN reported to Wake to assume overall command of U.S. forces on the island. He had 10 days to examine the defenses and assess his men before war broke out.

On 6 December, Japanese Submarine Division 27 (Ro-65, Ro-66, Ro-67) was dispatched from Kwajalein Atoll to patrol and blockade the pending operation.

December 7 was a clear and bright day on Wake Island. Just the previous day, Major Devereux did a practice drill for his Marines, which happened to be the first one done because of the great need to focus on the island's defenses. The drill went well enough that Major Devereux commanded the men to rest on the Sabbath and take their time relaxing, doing laundry, writing letters, thinking, cleaning, or doing whatever they wished.[12]

Initial attacks

On 8 December, just hours after receiving word of the attack on Pearl Harbor (Wake being on the opposite side of the International Date Line), 36 Japanese Mitsubishi G3M3 medium bombers flown from bases on the Marshall Islands attacked Wake Island, destroying eight of the 12 F4F-3 Wildcats on the ground[13] and sinking the Nisqually, a former Design 1023 cargo ship converted into a scow.[14] The remaining four Wildcats were in the air patrolling, but because of poor visibility, failed to see the attacking Japanese bombers. These Wildcats shot down two bombers on the following day.[15] All of the Marine garrison's defensive emplacements were left intact by the raid, which primarily targeted the aircraft. Of the 55 Marine aviation personnel, 23 were killed and 11 were wounded.

Following this attack, the Pan Am employees were evacuated, along with the passengers of the Philippine Clipper, a passing Martin 130 amphibious flying boat that had survived the attack unscathed. The Chamorro working men were not allowed to board the plane and were left behind.[16]

Two more air raids followed. The main camp was targeted on 9 December, destroying the civilian hospital and the Pan Am air facility. The next day, enemy bombers focused on outlying Wilkes Island. Following the raid on 9 December, the four antiaircraft guns had been relocated in case the Japanese had photographed the positions. Wooden replicas were erected in their place, and the Japanese bombers attacked the decoy positions. A lucky strike on a civilian dynamite supply set off a chain reaction and destroyed the munitions for the guns on Wilkes.[16]

First landing attempt

Early on the morning of 11 December, the garrison, with the support of the four remaining Wildcats, repelled the first Japanese landing attempt by the South Seas Force, which included the light cruisers Yubari, Tenryū, and Tatsuta; the relatively old Mutsuki and Kamikaze-class destroyers Yayoi, Mutsuki, Kisaragi, Hayate, Mochizuki and Oite, submarine tender Jingei, two armed merchantmen (Kinryu Maru and Kongō Maru), and two Momi-class destroyers converted to patrol boats that were reconfigured in 1941 to launch a landing craft over a stern ramp (Patrol Boat No. 32 and Patrol Boat No. 33) containing 450 Special Naval Landing Force troops. Submarines Ro-65, Ro-66, and Ro-67 patrolled nearby to secure the perimeter.

The US Marines fired at the invasion fleet with their six 5-inch (127 mm) coast-defense guns. Major Devereux, the Marine commander under Cunningham, ordered the gunners to hold their fire until the enemy moved within range of the coastal defenses. "Battery L", on Peale islet, sank Hayate at a distance of 4,000 yd (3,700 m) with at least two direct hits to her magazines, causing her to explode and sink within two minutes, in full view of the defenders on shore. Battery A claimed to have hit Yubari several times, but her action report makes no mention of any damage.[2] The four Wildcats also succeeded in sinking the destroyer Kisaragi by dropping a bomb on her stern where the depth charges were stored, although some also suggest the bomb hitting elsewhere and an explosion amidships.[17][18] Two destroyers were thus lost with nearly all hands (there was only one survivor, from Hayate), with Hayate becoming the first Japanese surface warship to be sunk in the war. The Japanese recorded 407 casualties during the first attempt.[2] The Japanese force withdrew without landing, suffering their first setback of the war against the Americans.

After the initial raid was fought off, American news media reported that, when queried about reinforcement and resupply, Commander Cunningham was reported to have quipped, "Send us more Japs!" In fact, Cunningham sent a long list of critical equipment—including gunsights, spare parts, and fire-control radar—to his immediate superior: Commandant, 14th Naval District.[19] But the siege and frequent Japanese air attacks on the Wake garrison continued, without resupply for the Americans.

Aborted USN relief attempt

Admiral Fletcher's Task Force 14 (TF–14) was tasked with the relief of Wake Island while Admiral Brown's Task Force 11 (TF–11) was to undertake a raid on the island of Jaluit in the Marshall Islands as a diversion. A third task force, under Vice Admiral Halsey, centred around the Enterprise was tasked with supporting the other two task forces as the Japanese Second Carrier Division (第二航空戦隊) remained in the area of operations, presenting a significant risk.[20]

TF–14 consisted of the fleet carrier Saratoga, the fleet oiler Neches, the seaplane tender Tangier, three heavy cruisers (Astoria, Minneapolis, and San Francisco), and 8 destroyers (Selfridge, Mugford, Jarvis, Patterson, Ralph Talbot, Henley, Blue, and Helm).[21] The convoy carried the 4th Marine Defense Battalion (Battery F, with four 3-inch AA guns, and Battery B, with two 5-inch/51 guns) and fighter squadron VMF-221, equipped with Brewster F2A-3 Buffalo fighters, along with three complete sets of Fire Control equipment for the 3-inch AA batteries already on the island, plus tools and spares; spare parts for the 5-inch coast defense guns and replacement fire control gear; 9,000 5-inch rounds, 12,000 3-inch (76 mm) rounds, and 3 million .50-inch (12.7 mm) rounds; machine gun teams and service and support elements of the 4th Defense Battalion; VMF-221 Detachment (the planes were embarked on Saratoga); as well as an SCR-270 air search radar and an SCR-268 fire control radar for the 3-inch guns, and a large amount of ammunition for mortars and other battalion small arms.

TF–11 consisted of the fleet carrier Lexington, the fleet oiler Neosho, three heavy cruisers (Indianapolis, Chicago and Portland), and the nine destroyers of Destroyer Squadron 1 (squadron flagship Phelps along with Dewey, Hull, MacDonough, Worden, Aylwin, Farragut, Dale, and Monaghan).[20]

At 21:00 on 22 December, after receiving information indicating the presence of two IJN carriers and two fast battleships (which were actually heavy cruisers) near Wake Island, Vice Admiral William S. Pye—the Acting Commander in Chief of the U.S. Pacific Fleet—ordered TF 14 to return to Pearl Harbor.[22]

Second assault

The initial resistance offered by the garrison prompted the Japanese Navy to detach the Second Carrier Division (Sōryū and Hiryū) along with its escorts 8th Cruiser Division (Chikuma and Tone), and the 17th Destroyer Division (Tanikaze and Urakaze), all fresh from the assault on Pearl Harbor; as well as 6th Cruiser Division (Kinugasa, Aoba, Kako, and Furutaka), destroyer Oboro, seaplane tender Kiyokawa Maru, and transport/minelayer Tenyo Maru from the invasion of Guam; and 29th Destroyer Division (Asanagi and Yūnagi) from the invasion of the Gilbert Islands, to support the assault.[23] The second Japanese invasion force came on 23 December, composed mostly of the ships from the first attempt plus 1,500 Japanese marines. The landings began at 02:35; after a preliminary bombardment, the Japanese landed at different points on the atoll. They were immediately faced with resistance by a "3" inch gun manned by Lieutenant Robert Hanna. His gun destroyed the ex-destroyers Patrol Boat No. 32 and Patrol Boat No. 33. The Japanese marines bypassed the gun position and attacked the airfield. Meanwhile a company of Japanese Special Naval Landing Forces Marines landed on Wake Island. They had advanced quite inland, until they were met with a strong US counterattack led by Captain Platt, which inflicted heavy casualties on the Japanese and forced them to retreat back to their landing area. After heavy fighting, the marines guarding the airfield retreated to a final line northeast of the airfield. A group of 100 SNLF marines infiltrated to this position and attacked it, causing the surrender of the island's garrison.

The US Marines lost 49 killed, two missing, and 49 wounded during the 15-day siege, while three US Navy personnel and at least 70 US civilians were killed, including 10 Chamorros, and 12 civilians wounded. 433 US personnel were captured. The Japanese captured all men remaining on the island, the majority of whom were civilian contractors employed by the Morrison-Knudsen Company.[24]

Japanese losses were 144 casualties, 140 SNLF and Army casualties with another 4 aboard ships.[3] At least 28 land-based and carrier aircraft were also either shot down or damaged.

Captain Henry T. Elrod, one of the pilots from VMF-211, was awarded the Medal of Honor posthumously for his actions on the island: he shot down two Japanese G3M Nells, sank the Japanese destroyer Kisaragi, and led ground troops after no flyable U.S. aircraft remained. A special military decoration, the Wake Island Device, affixed to either the Navy Expeditionary Medal or the Marine Corps Expeditionary Medal, was created to honor those who had fought in the defense of the island.

The only Marine to escape capture or death on Wake Island was Lieut. Col. Walter Bayler who departed on a United States Navy PBY Catalina on 20 December. He was therefore able to provide an accurate recounting of the actual happenings on Wake Island to the press and people of America, while also providing photos and maps of the island. He was also published in a nationwide magazine about the attack. The only reason Bayler was able to leave Wake Island was because he was a radio technician, and thus his services and abilities were greatly needed elsewhere. Therefore, he left in the only plane that was available.[25]

Japanese occupation

Fearing an imminent invasion, the Japanese reinforced Wake Island with more formidable defenses. The American captives were ordered to build a series of bunkers and fortifications on Wake. The Japanese brought in four 8-inch (200 mm) naval guns which are often incorrectly[26] reported as having been captured in Singapore. The U.S. Navy established a submarine blockade instead of an amphibious invasion of Wake Island. As a result, the Japanese garrison starved, which led to their hunting the Wake Island Rail, an endemic bird, to extinction.

On 24 February 1942, aircraft from the carrier Enterprise attacked the Japanese garrison on Wake Island. U.S. forces bombed the island periodically from 1942 until Japan's surrender in 1945. On 24 July 1943, Consolidated B-24 Liberators led by Lieutenant Jesse Stay of the 42nd Squadron (11th Bombardment Group) of the U.S. Army Air Forces, in transit from Midway Island, struck the Japanese garrison on Wake Island. At least two men from that raid were awarded Distinguished Flying Crosses for their efforts.[27] Future President George H. W. Bush also flew his first combat mission as a naval aviator over Wake Island. After this, Wake was occasionally raided but never attacked en masse.

War crimes

On 5 October 1943, American naval aircraft from Lexington raided Wake. Two days later, Japanese Naval Captain Shigematsu Sakaibara ordered the beheading of an American civilian worker who was caught stealing. He and 97 others had initially been kept to perform forced labor. Fearing an invasion, Sakaibara ordered all of them killed.[28] They were taken to the northern end of the island, blindfolded and executed with a machine gun. One of the prisoners (whose name has never been discovered) escaped, apparently returning to the site to carve the message "98 US PW 5-10-43" on a large coral rock near where the victims had been hastily buried in a mass grave. The unknown American was recaptured, and Sakaibara personally beheaded him with a katana. The inscription on the rock can still be seen and is a Wake Island landmark.[29]

On 4 September 1945, the remaining Japanese garrison surrendered to a detachment of United States Marines under the command of Brigadier General Lawson H. M. Sanderson, with the handover being officially conducted in a brief ceremony aboard the destroyer escort Levy.[30] Earlier the garrison received news that Imperial Japan's defeat was imminent, so the mass grave was quickly exhumed and the bones were moved to the U.S. cemetery that had been established on Peacock Point after the invasion, with wooden crosses erected in preparation for the expected arrival of U.S. forces. During the initial interrogations, the Japanese claimed that the remaining 98 Americans on the island were mostly killed by an American bombing raid, though some escaped and fought to the death after being cornered on the beach at the north end of Wake Island.[31] Several Japanese officers in American custody committed suicide over the incident, leaving written statements that incriminated Sakaibara.[32] Sakaibara and his subordinate, Lt. Cmdr. Tachibana, were later sentenced to death after conviction for this and other war crimes. Sakaibara was executed by hanging in Guam on June 19, 1947, while Tachibana's sentence was commuted to life in prison.[33] The remains of the murdered civilians were exhumed and reburied at Section G of the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, commonly known as Punchbowl Crater, on Honolulu.[34]

Order of battle

American forces

- CinCPac

- Commandant, 14th Naval District

- Island Commander, Wake. Cmdr. Winfield S. Cunningham, USN

- Commandant, 14th Naval District

| 1st Marine Defense Battalion Detachment, Wake – Major James P.S. Devreaux | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unit | Commander | Remarks | |||||||||||

| 5-inch Artillery Group | Maj. George H. Potter | Batteries A, B and L | |||||||||||

| 3-inch Artillery Group | Capt. Bryght D. Godbold | Batteries D, E and F | |||||||||||

| VMF-211 (Marine Corps Fighter Squadron) | Maj. Paul A. Putnam | Equipped with 12 Grumman F4F-3 Wildcat fighters | |||||||||||

Notes

- Naval and air personnel not included.

- Dull 2007, p. 24.

- Dull 2007, p. 26.

- Martin Gilbert, the Second World War (1989) p. 282

- "US ships lost in the Pacific during World War II". USMM.org. Retrieved 3 January 2014.

- 20 later died in captivity

- "The Defense of Wake". Ibiblio.org/.

- "War in the Pacific NHP: Liberation - Guam Remembers". nps.gov. Archived from the original on 2012-12-17. Retrieved 2014-09-13.

- 1st Marine Defense Battalion Archived August 25, 2005, at the Wayback Machine

- with only 449 Marines on hand for the battles at Wake Island because one officer [Major Walter Baylor], USMC had been ordered to leave on 20 December with official reports.

- Urwin, Gregory J. W. (2011). Victory in Defeat: The Wake Island Defenders in Captivity. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-61251-004-0.

- Moran, Jim (2011). Wake Island 1941: A battle to make the gods weep. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84908-943-2.

- Urwin, Gregory. "Battle of Wake Island". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- "US ships lost in the Pacific during World War II". USMM.org. Retrieved 3 January 2014.

- "Battle of Wake Island, 8–23 December 1941". historyofwar.org. Retrieved 2014-09-13.

- Cunningham, W. Scott (1961). Wake Island Command. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company. OCLC 464544704.

- Nevitt, Allyn D.; Tully, Anthony D. (July 2014). "IJN Kisaragi: Tabular Record of Movement". Long Lancers. Combinedfleet.com. Retrieved 10 November 2015.

- Wukovits 2003, p. 109.

- Cressman, Robert J. (1998). Frank, Benis M. (ed.). A Magnificent Fight: Marines in the Defense of Wake Island. World War II Commemorative Series. Washington, D.C.: Marine Corps Historical Center. Retrieved June 10, 2006.

- Nasuti, Guy (December 2016). "The Forsaken Defenders of Wake Island". Naval History and Heritage Command.

- Wheeler, Gerald E. (1996). Kinkaid of the Seventh Fleet: A Biography of Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid, U.S. Navy. Naval Historical Center. p. 143. ISBN 978-0945274261.

- Lundstrom, John B. (1990). The First Team: Pacific Naval Air Combat from Pearl Harbor to Midway (1st Naval Institute Press pbk. ed.). Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-59114-471-X. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- Heinly Jr., R. D. The Defense of Wake (PDF). Division of Public Information – United States Marine Corps.

- "A Magnificent Fight: Marines in the Battle for Wake Island". Archived from the original on May 12, 2014.

- Conville, Martin (23 May 1943). "Full Story of Desperate Wake Island Battle Told". Los Angeles Times. p. C5. ProQuest 165422622.

- "Dirk H.R. Spennemann, 8-inch Coastal Defense Guns". marshall.csu.edu.au. 9 October 2005. Retrieved 2014-09-13.

- Scearce, Phil; "Finish Forty and Home", pp. 113–114.

- Padden, Kathy Copeland (2021-05-29). "Wake Island War Crimes". Medium. Retrieved 2022-07-12.

- "The 98 Rock". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved 2019-01-16.

- Jim Moran (2011). Wake Island 1941: A battle to make the gods weep. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 84, 92. ISBN 978-1-84908-604-2.

- Maj. Mark E. Hubbs, U.S. Army Reserve (Retired). "Massacre on Wake Island". Archived from the original on February 14, 2008. Retrieved February 18, 2011.

- "Sakaibara Shigematsu | Japanese military officer". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-01-16.

- Headsman (2009-06-18). "1947: Shigematsu Sakaibara, "I obey with pleasure"". ExecutedToday.com.

- Administration, National Cemetery. "National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific". www.cem.va.gov. Retrieved 2019-01-16.

References

- Dull, Paul (2007). A Battle History of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1941–1945. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1591142195.

Further reading

- Burton (2006). Fortnight of Infamy: The Collapse of Allied Airpower West of Pearl Harbor. US Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-59114-096-X.

- Cressman, Robert J. (2005). A Magnificent Fight: The Battle for Wake Island. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-140-8.

- Cunningham, Chet (2002). Hell Wouldn't Stop: An Oral History of the Battle of Wake Island. Carroll & Graf. ISBN 0-7867-1096-9.

- Dennis, Jim Moran (2011). Wake Island 1941: a battle to make the gods weep. Osprey Campaign Series. Vol. 144. Illustrated by Peter Dennis. Oxford: Osprey Pub. ISBN 978-1-84908-603-5.

- Devereux, Colonel James P.S. (1997) [First published 1947]. The story of Wake Island. Nashville: Battery Press. ISBN 0-89839-264-0.

- Sloan, Bill (2003). Given up for dead: America's heroic stand at Wake Island. New York: Bantam Books. ISBN 0-553-80302-6.

- Toll, Ian W. (2011). Pacific Crucible: War at Sea in the Pacific, 1941–1942. New York: W. W. Norton.

- Uwrin, Gregory J.W. (1997). Facing Fearful Odds: The Siege of Wake Island. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-9562-6.

- Wukovits, John (2003). Pacific Alamo: The Battle for Wake Island. NAL Trade. ISBN 0-451-20873-0.

External links

- The Defense of Wake

- A Magnificent Fight: Marines in the Battle for Wake Island

- A Virtual Cemetery for Wake Island Defenders on Find A Grave

- Wake Island Account

- Wake Island Civilian POW Account

- Wake Island Civilian POW Account

- Executed Today on the executed Civilians

- Massacre on wake Island

- Wake island Roster Bonita Gilbert website

- Wake Island (1942) at IMDb

- Wake Island: Alamo of the Pacific (2003) at IMDb

- Spennemann, Dirk H.R. (2000–2005). "To Hell and Back: Wake During and After World War II". Digital Micronesia. Charles Sturt University. Retrieved 2007-01-23.