Battles of the Kinarot Valley

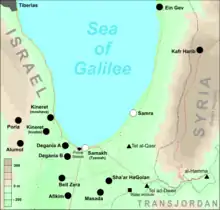

The Battles of the Kinarot Valley (Hebrew: הַמַּעֲרָכָה בְּבִקְעַת כִּנָּרוֹת, HaMa'arakha BeBik'at Kinarot), is a collective name for a series of military engagements between the Haganah and the Syrian army during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, fought between 15–22 May 1948 in the Kinarot Valley. It includes two main sites: the Battle of Degania–Samakh (Tzemah), and battles near Masada–Sha'ar HaGolan. The engagements were part of the battles of the Jordan Valley, which also saw fighting against Transjordan in the area of Gesher.

| Battles of the Kinarot Valley | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the 1948 Arab–Israeli War | |||||||

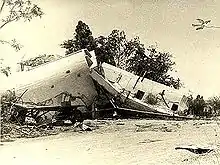

Preserved Renault R35 tank destroyed by Israel at Degania. The PIAT's hit can be seen at the top of the turret. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| ~80 (Degania Bet)[3] |

Infantry brigade, Tank battalion, Two armored vehicle battalions, Artillery battalion[4] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

8 (Degania Alef)[5] 54 (Tzemah)[3] | 45 (Israeli estimate) | ||||||

The battles took place approximately 24 hours after the Israeli declaration of independence, when Syria shelled Ein Gev on the night of 15–16 May. This was the first military engagement between Israel and Syria. On 18 May, Syria attacked the Israeli forward position in Samakh (Tzemah), and on 20 May attacked Degania Alef and occupied Masada and Sha'ar HaGolan. The attack on Degania Alef was a failure, after which the Syrian forces attempted to capture Degania Bet. After reaching a stalemate, they retreated to their initial position in Tel al-Qasr, where they remained until the end of the war.

The campaign was perceived as a decisive Israeli victory, causing reorganizations in the Syrian high command and the birth of heroic tales in Israel. However, Syria made a small territorial gain and certain actions were criticized within Israel, such as the retreat from Masada and Sha'ar HaGolan.

Background

The first stage of the 1948 War started following the ratification of UN Resolution 181 on 29 November 1947, which granted Israel the mandate to declare independence.[6] This was declared on 14 May 1948 and the next night, the armies of a number of Arab states invaded Israel and attacked Israeli positions.[7][8]

The Arab states surrounding the Mandate of Palestine started to prepare themselves a few weeks before 15 May. According to the Arab plan, the Syrian army was to attack the new state from southern Lebanon and capture Safed.[9] As such, the Syrians massed their forces in that area; however, after they found out that Lebanon did not wish to actively participate in combat, their plans changed to an attack from the southern Golan Heights on Samakh (Tzemah) and later Tiberias.[10] The Syrian force assembled in Qatana on 1 May. It moved on 12 May to Beirut and to Sidon on 13 May, after which it headed to Bint Jbeil. After the sudden plan change, the force moved to Nabatieh, and proceeded around the Finger of the Galilee to Banias and Quneitra, from which the eventual attack was staged.[4]

The Syrian Army was meant to consist of two brigade-sized units, but there was no time to prepare them, thus only the 1st Brigade was in a state of readiness by 15 May. It had about 2,000 soldiers in two infantry battalions, one armored battalion, and 4–6 artillery batteries.[11]

Prelude

According to plan, the Syrians attacked from the southern Golan Heights, just south of the Sea of Galilee through al-Hama and the Yarmouk River, hitting a densely populated Jewish area of settlement. This came as a surprise to the Haganah,[10] which expected an attack from south Lebanon and Mishmar HaYarden.[12] The Jewish villages on the original confrontation line were Ein Gev, Masada, Sha'ar HaGolan and Degania Alef and Beit.

On Friday, 14 May, the Syrian 1st Infantry Brigade, commanded by Colonel Abdullah Wahab el-Hakim, was in Southern Lebanon, positioned to attack Malkia. That day Hakim was ordered to return to Syria, move south across the Golan and enter Palestine south of the Sea of Galilee through Samakh (Tzemah). He began to advance at 9:00 AM on Saturday and had only two of his battalions, where the soldiers were already exhausted.[13]

At the onset of the invasion, the Syrian force consisted of a reinforced infantry brigade, supplemented by at least one armored battalion (including Renault R35 tanks) and a field artillery battalion.[1][4] The troops moved to Kafr Harib and were spotted by Haganah reconnaissance, but because the attack was not expected, the Israeli troops did not attack the invaders.[10] At night between 15 and 16 May, the bulk of the Syrian forces set up camp in Tel al-Qasr in the southwestern Golan. One company with armored reinforcements split up to the south to proceed to the Jewish water station on the Yarmouk riverbank.[1]

The Haganah forces in the area consisted of several units from the Barak (2nd) Battalion of the Golani Brigade, as well as the indigenous villagers, including a reduced Guard Corps (HIM) company at the Samakh (Tzemah) police station.[1] This force was headed by the battalion commander's deputy, who was killed in action in the battle.[14] On 13 May, the battalion commander declared a state of emergency in the area from 15 May until further notice. He authorized his men to seize all necessary arms from the settlements and urged them to dig in and build fortifications as fast as possible, and to mobilize all the necessary work force to do so.[15]

Battles

On Saturday night, 15 May, the observation posts reported many vehicles with full lights moving along the Golan ridge east of the Sea of Galilee.[16] The opening shots were fired by Syrian artillery on kibbutz Ein Gev at approximately 01:00 on 16 May. At dawn, Syrian aircraft attacked the Kinarot valley villages. The following day, a Syrian company which split from the main force attacked the water station with heavy weaponry, where every civilian worker was killed except one.[17]

An Israeli reserve unit was called in from Tiberias. It arrived after twenty minutes and took positions around the town. At that point, Samakh (Tzemah) was defended by three platoons from the Barak battalion and reinforcements from neighboring villages.[16] They entrenched in the actual village,[1] which had been abandoned by the residents in April 1948, with British escort.[18] Positions in the village included the police station in the west, the cemetery in the north, the Manshiya neighborhood in the south, and the railway station.[17] The Syrians set up their positions in an abandoned British military base just east of the village and in an animal quarantine station to the southeast.[1]

Two Israeli sappers were sent to mine the area of the quarantine station, but did not know that it was already under Syrian control. Their vehicle was blown up, but they managed to escape alive.[17] On the same day, the Syrian company that attacked the water station from Tel ad-Dweir proceeded towards Sha'ar HaGolan and Masada. Its advance was halted by the village residents as well as a platoon of reinforcements armed with 20 mm cannons. The company retreated to its position and commenced artillery fire on the two kibbutzim.[1]

This development gave the Israeli forces time to organize their defenses at Samakh (Tzemah). During the course of 16 May, Israeli gunboats harassed the Syrian positions on the southeastern Sea of Galilee shore, trenches were dug, and roadblocks were set up. Meanwhile, Syrian aircraft made bombing runs on Masada, Sha'ar HaGolan, Degania Bet and Afikim.[1] The attack on Samakh (Tzemah) resumed before dawn on 17 May—the Syrians attacked the village's northern positions, but their armor stayed behind. The infantry thus could not advance into the concentrated Israeli fire from the village itself, despite severe ammunition shortages on the Israeli side.[17]

Meanwhile, the defenders of Tiberias believed their town would be targeted next, and built barricades and fortifications. Ben-Gurion told the cabinet that "The situation is very grave. There aren't enough rifles. There are no heavy weapons".[19] Aharon Israeli, a platoon leader, commented that there was also a severe lack of experienced field commanders—he himself was hastily promoted on 15 May, despite not having sufficient knowledge or experience.[20] Also on 16 May, the Syrian President, Shukri al-Quwatli, visited the front with his Prime Minister, Jamil Mardam, and his Defense Minister, Taha al-Hashimi. He told his forces "to destroy the Zionists".[19]

At night, a Syrian force attempted to surround the Israelis by crossing the Jordan River to the north of the Sea of Galilee, but encountered a minefield in which a senior Syrian officer was wounded.[1] This was spotted and reported by the Israelis at Tabgha,[21] and the additional reprieve allowed the Kinarot Valley villages to evacuate the children, elderly and sick, as well as conduct maneuvers which feigned massive reinforcements in the Poria-Alumot region.[1] In the panic of surprise, many men also tried to flee the frontal villages, but blockposts were set up near Afula and Yavne'el by the Military Police Service's northern command, under Yosef Pressman, who personally stopped buses and allowed only the women and children to proceed to safety.[22]

Samakh (Tzemah)

At about 04:30 on 18 May,[23] the Syrian 1st Brigade, now commanded by Brigadier General Husni al-Za'im and consisting of about 30 vehicles, including tanks, advanced west towards Samakh (Tzemah) in two columns—one across the coast, and another flanking from the south. A contingent was allocated further south, in order to secure the safety of the main force by flanking Sha'ar HaGolan and Masada from the west. It entered a stalemate with a new Israeli position northwest of the two villages.[1][24]

The coastal column shelled the Israeli positions and inflicted enormous damage; the Israelis were either dug in within shallow trenches made for infantry warfare with no head cover, or in Samakh's clay houses that were vulnerable to heavy weapons. The Israelis were eventually forced to abandon their posts and concentrate in the police station, where they brought the wounded. The deputy commander of the Golani Brigade, Tzvika Levkov, also arrived at the station, and called reinforcements from Sha'ar HaGolan and Tiberias, which did not manage to arrive on time.[23]

A soldier who participated in the battle reported that only 20 uninjured troops were left to defend the police station as the second Syrian column reached Samakh (Tzemah). The only heavy weapon the defenders possessed was ineffective against Syrian armor.[23] Fearing their forces would be completely cut off, an order was given by the Haganah to retreat and leave the wounded, Tzvika Levkov among them. The retreat was disorganized and heavy Israeli casualties were recorded as Samakh's police station fell.[1][24] Reinforcements from the Deganias, commanded by Moshe Cohen, arrived but were immediately hit by the Syrians and did not significantly affect the battle.[1] Aharon Israeli, a platoon commander in these reinforcements, wrote that it was clear as soon as they arrived that the battle was over. Cohen would not hear of a retreat initially, but when the force saw Levkov fall into a trench, they hastily withdrew.[25]

On the same day, Syrian aircraft bombed the Israeli village Kinneret and the regional school Beit Yerah, on the southwestern shore of the Sea of Galilee. By evening, Samakh (Tzemah) had fallen and a new Israeli defensive line was set up in the Deganias, facing the Syrian counterparts.[1] At night, a Palmach company from Yiftach's 3rd Battalion attempted to recapture Samakh's police station. They stealthily reached the school next to the station, but the assault on the actual fort was warded off.[26] On the morning of 19 May, a message was sent from Sha'ar HaGolan and Masada that they were preparing for an evacuation, although when the order was given to stay put, the villages had already been abandoned, mostly to Afikim.[1] In the morning, when the villagers carried out an order to return to their positions, local Arabs were already present at the location.[26] The Syrian troops then captured the villages without a fight,[24] and proceeded to loot and destroy them.[27] Aharon Israeli wrote that an order was given not to disclose the flight of Masada and Sha'ar HaGolan's residents, but this became clear as fire and smoke rose from the villages, and hurt the morale of the Israelis making defensive preparations in the Deganias.[28]

The counterattack on the police station failed but delayed the Syrian attack on the Deganias by twenty-four hours. In the evening of 19 May, a delegation from the Deganias arrived in Tel Aviv to ask for reinforcements and heavy weapons. One of its members later wrote that David Ben-Gurion told them he could not spare them anything, as "The whole country is a front line". He also wrote that Yigael Yadin, the Chief Operations Officer of the Haganah, told him that there was no alternative to letting the Arabs approach to within twenty to thirty meters of the gates of Degania and fight their tanks in close combat.[29] Yadin prepared reinforcements, and gave an order: "No point should be abandoned. [You] must fight at each site". He and Ben-Gurion argued over where to send the Yishuv's only battery of four pre-World War I 65 mm mountain guns (nicknamed "Napoleonchikim"), which had no proper sights. Ben-Gurion wanted to send them to Jerusalem, but Yadin insisted that they be sent to the Kinarot valley, and Ben-Gurion eventually agreed.[30]

On the night of 18–19 May, a platoon departed from Ein Gev by sea to Samra and raided the Syrian contingent in Tel al-Qasr. The raid failed, but may have delayed the Syrian attack on Degania, thus giving its defenders twenty-four hours to prepare. A second raid, by a Yiftach company, crossed the Jordan and struck the Syrian camp at the Customs House, near the main Daughters of Jacob Bridge (Bnot Yaakov Bridge). After a short battle, the Syrian defenders (one or two companies) fled. The Palmachniks destroyed the camp and several vehicles, including two armored cars, without losses.[31]

Degania Alef

After the fall of Tzemah, the Haganah command realized the importance of the campaign in the region, and made a clear separation between the Kinarot Valley, and the Battle of Gesher fought against Transjordan[32] and Iraq to the south.[3] On 18 May, Moshe Dayan, who had been born in Degania, was given command of all forces in the area, after having been charged with creating a commando battalion in the 8th Brigade just a day before.[33][34] A company of reinforcements from the Gadna program was allocated, along with 3 PIATs. Other reinforcements came in the form of a company from the Yiftach Brigade and another company of paramilitaries from villages in the Lower Galilee and the Jezreel Valley.[1]

The Israelis called the reinforcements assuming this was the main Syrian thrust. The Syrians were not intending to carry out any further operation south of the Sea of Galilee and planned to make their main effort further north, near the Bnot Ya'akov bridge. On 19 May, the Iraqis were about to drive west through Nablus toward Tulkarm, and asked the Syrians to make a diversion in the Degania area to protect their right flank. The Syrians complied, their main objective being to seize the bridge across the river north of Degania Alef, thus blocking any Israeli attack from Tiberias against the Iraqi line of communications.[24]

Heavy Syrian shelling of Degania Alef started at about 04:00 on 20 May from the Samakh police station, by means of 75 mm cannons, and 60 and 81 mm mortars.[21] The barrage lasted about half an hour.[30] At 04:30 on 20 May, the Syrian army began its advance on the Deganias and the bridge over the Jordan River north of Degania Alef.[5] Unlike the attack on Samakh (Tzemah), this action saw the participation of nearly all of the Syrian forces stationed at Tel al-Qasr, including infantry, armor and artillery.[1] The Israeli defenders numbered about 70 persons (67 according to Aharon Israeli's head count[28]), most of them not regular fighters, with some Haganah and Palmach members. Their orders were to fight to the death. They had support from three 20 mm guns at Beit Yerah, deployed along the road from Samakh to Degania Alef. They also had a Davidka mortar, which exploded during the battle, and a PIAT with fifteen projectiles.[30]

At night, a Syrian expeditionary force attempted to infiltrate Degania Bet, but was caught and warded off, which caused the main Syrian force to attack Degania Alef first.[1] At 06:00, the Syrians started a frontal armored attack, consisting of 5 tanks, a number of armored vehicles and an infantry company.[5] The Syrians pierced the Israeli defense, but their infantry was at some distance behind the tanks. The Israelis knocked out four Syrian tanks and four armored cars with 20 mm cannons, PIATs and Molotov cocktails.[35] Meanwhile, other defenders kept small arms fire on the Syrian infantry, who stopped in citrus groves a few hundred meters from the settlements. The surviving Syrian tanks withdrew back to the Golan.[24] At 07:45, the Syrians halted their assault and dug in, still holding most of the territory between Degania Alef's fence and Samakh's police fort.[30] They left behind a number of lightly damaged or otherwise inoperable tanks that the Israelis managed to repair.[36]

Degania Bet

Despite the Syrian superiority in numbers and equipment, the destruction of a multitude of armored vehicles and the infantry's failure to infiltrate Degania Alef was the likely cause for the retreat of the main Syrian force to Samakh (Tzemah). A less-organized and sparsely numbered armored and infantry force forked off to attack Degania Bet.[1] Eight tanks, supported by mortar fire, moved within 400 yards of the settlement defense, where they stopped to provide fire support for an infantry attack. The Syrians made two failed attempts to breach the Israeli small arms fire defense and gave up the attempt.[37] Against this force, the Israelis had about 80 people and one PIAT.[38] The defenses in Degania Bet were disorganized and there were not enough trenches. They also had no communication link to the command, so Moshe Dayan sent one of his company commanders to assess the situation.[39]

While the battle was taking place, the 65 mm artillery, four Napoleonchik canons, reached the front in the middle of the day and were placed on the Poria–Alumot ridge.[1] It was the first Israeli artillery to be used in the war.[37] At 13:20, they began to fire at the Syrians, and after about 40 rounds the latter began to retreat.[40] The Israelis also fired into Samakh, where the Syrian officers, who had until then believed that the Israelis had nothing that could hit their headquarters, took shelter. One projectile hit the Syrian ammunition depot in the village, and others ignited fires in the dry fields.[38] While the soldiers who operated the cannons (still lacking sights) were not proficient in handling them, an acceptable level of accuracy was achieved after practice shots into the Sea of Galilee. In all, the artillery fire took the Syrian army by complete surprise, and the latter decided to regroup and retreat to Tel al-Qasr, also recalling the company at Sha'ar HaGolan and Masada.[1] A total of 500 shells were fired by the Israeli artillery.[39] Syrian officers may have shot some of their fleeing soldiers.[38]

There were two other reasons for the Syrian withdrawal. The 3rd Battalion from the Palmach's Yiftach Brigade had been sent by boat during the previous night across the sea to Ein Gev, planning to assault and capture Kafr Harib. It was noticed and shelled by the Syrians, but one of the companies managed to climb up the Golan. It carried out a smaller raid at dawn, bombing water carriers and threatening the Syrian 1st Brigade's line of communications.[37][41] The second reason was that they were running out of ammunition: Husni al-Za'im had been promised replenishment, and attacked Degania short of ammunition. Za'im ordered a withdrawal when his troops ran out of ammunition. The replenishment was instead sent to the 2nd Brigade further north. The Israelis were not aware of this, and attributed the Syrian withdrawal to surprise at the Israeli artillery fire.[37]

Aftermath and effects

On 21 May, Haganah troops returned to Samakh (Tzemah) and set up fortifications,[1] The damaged tanks and armored cars were gathered and taken to the rear. The settlers returned that night to identify the bodies of their comrades in the fields and buried them in a common grave in Degania.[42] At dawn on 21 May, the Golani staff reported that the enemy was repelled but that they were expecting another attack. The full report read:

Our forces repelled yesterday a heavy attack of tanks, armored vehicles and infantry that lasted about 8 hours. The attack was repelled by the brave stand of our men, who used Molotov cocktails and their hands against the tanks. 3" mortars and heavy machinery took their toll on the enemy. Field cannons caused a panicked retreat of the enemy, who yesterday left Tzemah. This morning our forces entered Tzemah and took a large amount of booty of French ammunition and light artillery ammunition. We have captured 2 tanks and an armored vehicle of the enemy. The enemy is amassing large reinforcements. We are expecting a renewal of the attack.[21]

On 22 May, villagers returned to Masada and Sha'ar HaGolan, which had been largely destroyed.[1] Expecting another attack, reinforcements from the Carmeli Brigade took up positions in the two villages.[21] Many of the participants of the battles were sent to Tiberias to rest and recuperate, and the units that lost soldiers were reorganized.[43]

In the wake of the fall of Gush Etzion, news of Degania's successful stand (as well as that of Kfar Darom) provided a morale boost for other Israeli villages.[44] The battle also influenced British opinion on the balance of power in the war.[45] The success of the Napoleonchik field cannons prompted the Israeli high command to re-use two of them in attempts to capture Latrun.[21] The flight from Masada and Sha'ar HaGolan, on the other hand, stirred controversy in the young state, fueled by news of the Kfar Etzion massacre just days before, and the Palmach issued a newsletter accusing them of abandoning national assets, among other things. These accusations were subsequently repeated in media and in a play by Yigal Mossensohn, and a campaign was started by the villagers to clear their name.[27]

The battles of the Kinarot Valley were the first and last of the major ground engagements between Israel and Syria to the south of the Sea of Galilee, although minor patrol skirmishes continued until the first ceasefire.[21] The campaign, combined with the Battle of Gesher, was possibly the only coordinated attack between two or more Arab countries in the northern front.[41] At the end, the Syrians held Tel al-Qasr, which was part of the British Mandate of Palestine and the Jewish state according to the UN partition of 1947. Despite the above, the offensive was considered a decisive Syrian defeat by both sides. The Syrian defense minister Ahmad al-Sharabati and Chief of Staff Abdullah Atfeh blamed each other, the latter resigning and the former being dismissed by the prime minister as a result of the battle.[4] As reasons for their defeat, they gave their low level of preparedness and the strength of the Israeli defenses, as well as their lack of coordination with the Iraqis (according to one Syrian historian, the Iraqis were supposed to assist them in the Deganias). After the battle, British observers became convinced that the Arabs were not going to win the war, and compared the battle to the Luftwaffe's failure in the Battle of Britain in 1940, which showed that Germany was not going to win the air war. The observers said that "A greater edge than the [Syrians] enjoyed at Degania they won't have again".[45]

First tank kill controversy

The first Syrian tank damaged near Degania Alef's gates, which has been preserved on the location, was the subject of a historiographic dispute when Baruch "Burke" Bar-Lev, a retired IDF colonel and one of Degania's native defenders at the time, claimed that he was the one who stopped the tank with a Molotov cocktail.[46] However, his account was rebutted by an IDF Ordnance Corps probe, which in 1991 determined that a PIAT shot had killed the tank's crew. Shlomo Anschel, a Haifa resident who also participated in the battle, told Haaretz in 2007 that the tank was hit by PIAT fire from a Golani soldier, and that the Molotov cocktail could not possibly have hit the crew.[47]

References

- Wallach et al. (1978), pp. 14–15

- "The Battle for Degania" (in Hebrew). Israel Defense Forces. Archived from the original on 15 September 2008. Retrieved 28 January 2009.

- Morris (2008), p. 254

- Gelber (2006), p. 141

- Yitzhaki (1988), pp. 97–101

- Morris (2004), pp. 12–13

- Gelber (2006), pp. 138–142

- "Israeli War of Independence". GlobalSecurity.org. Archived from the original on 18 January 2009. Retrieved 28 January 2009.

- Gelber (2006), p. 134

- Gelber (2006), p. 136

- Morris (2008), p. 251

- Gelber (2006), p. 135

- Dupuy (2002), p. 47

- IDF History (1978), p. 169

- Lorch (1968), pp. 170–171

- Lorch (1968), p. 171

- Etzioni (1951), pp. 165–166

- Gelber (2006), p. 101

- Morris (2008), pp. 253–254

- Etzioni (1951), pp. 171–172

- IDF History (1978), pp. 166–173

- Harel (1982), p. 15

- Etzioni (1951), pp. 166–168

- Dupuy (2002), p. 48

- Etzioni (1951), pp. 172–176

- Etzioni (1951), p. 168

- Ashkenazi, Eli (6 April 2006). "Zionist Mythology Destroys its Children". Haaretz. Retrieved 28 January 2009.

- Etzioni (1951), pp. 176–177

- Lorch (1968), p. 174

- Morris (2008), p. 255

- Morris (2008), pp. 254–255

- David Tal (31 January 2004). War in Palestine, 1948: Israeli and Arab Strategy and Diplomacy. Routledge. p. 202. ISBN 978-0-203-49954-2.

- Teveth (1972), p. 137

- Teveth (1972), p. 139

- Pollack (2002), p. 452

- Pollack (2002), p. 453

- Dupuy (2002), p. 49

- Morris (2008), p. 256

- Teveth (1972), p. 141

- Teveth (1972), p. 142

- Hadari, Danny in ed. Kadish, Alon (2005), pp. 138–141

- Lorch (1968), p. 176

- Etzioni (1951), p. 170

- Lorch (1968), p. 177

- Morris (2008), p. 257

- Dromi, Uri. "The Tank Crewman who Spoke of Idi Amin's Heart" (in Hebrew). Haaretz. Retrieved 28 January 2009.

- "The Battle of Degania" (in Hebrew). Haaretz. 16 August 2007. Retrieved 28 January 2009.

Bibliography

- Dupuy, Trevor N. (2002). Elusive Victory: The Arab–Israeli Wars, 1947–1974. Military Book Club. ISBN 0-9654428-0-2.

- Etzioni, Binyamin, ed. (1951). Tree and Dagger – Battle Path of the Golani Brigade (in Hebrew). Ma'arakhot Publishing.

- Broshi, Yitzhak: Battles of the Kinarot Valley, pp. 162–170 (in Hebrew)

- Israeli, Aharon: In the Campaign, pp. 171–177 (in Hebrew)

- Gelber, Yoav (April 2006). Palestine 1948: War, Escape And The Emergence Of The Palestinian Refugee Problem (2nd ed.). Sussex Academic Press. ISBN 1-84519-075-0.

- Harel, Zvi (1982). "Military Police Corps (Vol. 16)". In Yehuda Schiff (ed.). IDF in Its Corps: Army and Security Encyclopedia (in Hebrew). Revivim Publishing.

- Israel Defense Forces History General Staff Historiography Branch (1978) [First published in 1959]. History of the War of Independence (in Hebrew) (20th ed.). Israel: Ma'arakhot Publishing. S/N 501-202-72.

- Kadish, Alon, ed. (2005) [First published in 2004]. Israel's War of Independence 1948–49: Revisited (in Hebrew) (2nd ed.). Ministry of Defense. ISBN 965-05-1251-9.

- Lorch, Netanel (1968). The Edge of the Sword: Israel's War of Independence, 1947–1949. Jerusalem: Massada.

- Morris, Benny (2004). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-00967-7. Retrieved 28 January 2009.

- Morris, Benny (2008). 1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-15112-1.

- Pollack, Kenneth M. (1 September 2004). Arabs at War: Military Effectiveness, 1948–1991. Bison Books. ISBN 0-8032-8783-6. Retrieved 5 January 2010.

- Teveth, Shabtai (1972). Moshe Dayan. The Soldier, the Man, the Legend. Widenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-99522-7.

- Wallach, Jeuda; Lorch, Netanel; Yitzhaki, Aryeh (1978). "Battles of the Jordan Valley". In Evyatar Nur (ed.). Carta's Atlas of Israel (in Hebrew). Vol. 2 - The First Years 1948–1961. Jerusalem, Israel: Carta.

- Yitzhaki, Aryeh (1988). A Guide to War Monuments and Sites in Israel (English Title), Volume 1 - North (in Hebrew). Tel Aviv, Israel: Barr Publishers.