Fonthill Abbey

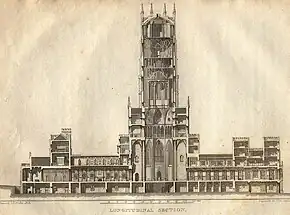

Fonthill Abbey—also known as Beckford's Folly—was a large Gothic Revival country house built between 1796 and 1813 at Fonthill Gifford in Wiltshire, England, at the direction of William Thomas Beckford and architect James Wyatt.[1][2] It was built near the site of the Palladian house, later known as Fonthill Splendens, which had been constructed by 1770 by his father William Beckford.[3] This, in turn, had replaced the Elizabethan house that Beckford the Elder had purchased in 1744 and which had been destroyed by fire in 1755. The abbey's main tower collapsed several times, lastly in 1825 damaging the western wing. The abbey was later almost completely demolished.

History

Fonthill Abbey was the brainchild of William Thomas Beckford, son of wealthy English plantation owner William Beckford and a student of architect Sir William Chambers, as well as of James Wyatt, architect of the project.

In 1771, when Beckford was ten years old, he inherited £1 million (equivalent to £96,950,000 in 2021)[4] and an income which his contemporaries estimated at around £100,000 per annum, a colossal amount at the time, but which biographers have found to be closer to half of that sum. Newspapers of the period described him as "the richest commoner in England".

He first met William Courtenay (Viscount Courtenay's 11-year-old son) in 1778. A spectacular Christmas party lasting for three days was held for the boy at Fonthill. During this time (c.1782), Beckford began writing Vathek, his most famous novel.[5] In 1784, Beckford was accused by Courtenay's uncle, the 1st Baron Lougborough, of having had an affair with Courtenay.[6] The allegations of misconduct remained unproven, but the scandal was significant enough to require his exile.

Beckford chose exile in the company of his wife, Lady Margaret Gordon, whom he grew to love deeply, but who died in childbirth after the couple had found refuge in Switzerland. Beckford travelled extensively after this tragedy—to France, repeatedly, to Germany, Italy, Spain, and Portugal (the country he favoured above all). Shunned by English society, he nevertheless decided to return to his native country; after enclosing the Fonthill estate in a six-mile long wall (high enough to prevent hunters from chasing foxes and hares on his property), the arch-romantic Beckford decided to have a Gothic cathedral built for his home.

Fonthill Abbey would be vast, reflecting "the aesthetic category of 'the Sublime' as defined by the philosopher Edmund Burke in the middle of the eighteenth century."[7]

Construction

Construction of the abbey began in earnest in 1796 on Beckford's estate of Fonthill Gifford near Hindon in southern Wiltshire. He hired James Wyatt, one of the most popular and successful architects of the late 18th-century, to lead the works. Wyatt was often accused of spending a good deal of his time on women and drink.[8] Consequently, he also angered many of his clients—including Beckford—because of his all too common absences from client meetings, for a general disregard for supervising the construction works he was in charge of, and for not delivering the promised results in time, with clients accusing him—in certain instances—of years of delay.[8]

Although suffering from a relationship which was at times strained, Beckford and Wyatt engaged in the construction of the abbey. It is clear, however, that Beckford, due to Wyatt's constant absences from the site, and because of the intense personal interest he had in the enterprise, often took on the roles of construction site supervisor, general organiser, and patron, as well as client. Indeed, his biographers and his correspondence indicate that, during Wyatt's prolonged absences, he took it upon himself to direct the construction of the Abbey, as well as leading the landscaping efforts on his estate.

Furthermore, the evidence suggests that not only was he happy to undertake all of those duties but, as Brockman[9] suggests, must even have lived some of the brightest moments of his adult life managing the gigantic efforts at Fonthill. This is not to say that Wyatt's role in the construction was by any means less than Beckford's. Wyatt had not only designed the building (based on Beckford's ideas), but was ultimately a master at combining the different volumes and scales. By combining different architectural styles and elements, Wyatt achieved a faux effect of layered historical development in the building.

Glass painter Francis Eginton did much work in the building, including thirty-two figures of kings, knights, etc., and many windows, for which Beckford paid him £12,000.

Beckford's 500 labourers worked in day and night shifts. To speed the work, he out-bid (some would say bribed) 450 more from the building of the new royal apartments at Windsor Castle by increasing an ale ration. He also commandeered all the local wagons for transportation of building materials. To compensate, Beckford delivered free coal and blankets to the poor in cold weather.

The first part to be built was the tower, which reached about 90 metres (300 ft) before it collapsed. The new tower was finished six years later, again 90 metres tall. It collapsed as well. Beckford immediately started to build another one, this time with stone, and this work was finished in seven years.

Decorations

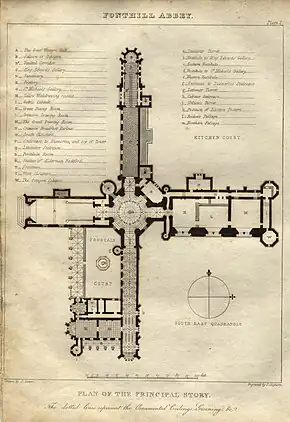

The abbey part was decorated in silver, gold, red and purple. Four long wings radiated from the octagonal central room. Its front doors were 35 feet (11 m) tall. It was declared finished in 1813.

Use

The approach to the abbey, some 900 metres long and named the Great Western Avenue, ran in a straight line through woodland ENE from the Hindon-Tisbury road. Beckford lived alone in his abbey and used only one of its bedrooms. His kitchens prepared food for 12 every day, although he always dined alone and sent the surplus food away afterwards. Only once, in 1800, did he entertain guests, when Horatio Nelson and Emma Hamilton visited the abbey for Christmas.

Once he stipulated that he would eat a Christmas dinner only if it were served from the new abbey kitchens, and told his workmen to hurry. The kitchens collapsed as soon as the meal was over.

Beckford lived in Fonthill Abbey until 1822 when he lost two of his Jamaican sugar plantations in a legal action. He was forced to sell it and its contents for £330,000 (equivalent to £31,990,000 in 2021)[4] to arms dealer John Farquhar.[10]

Collapse

Beckford's obsessive haste in erecting the grandiose building, coupled with his wish to achieve heights in the tower which were structurally unsound, and the use of a building method called "compo-cement" by Wyatt, which consisted of timber stuccoed with cement, led to the eventual collapse of the tower—damaging the western wing of the building too—in 1825. By this time, Beckford had already sold the building. He died in 1844 in Bath.

The rest of the abbey was demolished c. 1845. Only a small two-storey remnant of the north wing, with a four-storey tower, still stands; this fragment was designated as Grade II* listed in 1966.[11][12] Stone from the site, including windows and carvings, was used in the construction of buildings in nearby Tisbury.[13]

Fonthill New Abbey

The western part of Beckford's estate was later acquired by the 2nd Marquess of Westminster, who had a new Fonthill Abbey built in 1846–1852 (Pevsner)[14] or 1856–1859 (VCH),[15] some 500 metres southeast of the site of Beckford's abbey. This mansion, designed by William Burn in Scottish Baronial style, was demolished in 1955.

The stable buildings survive in residential use,[16] as do four lodges at estate entrances, built in or around 1860: Tisbury Lodge, south of Fonthill Gifford church, designed in matching Scottish style by Burn;[17] Lawn Lodge, further south along the same road, also by Burn but in plain ashlar;[18] West Gate Lodge, in the southwest of Beckford's estate, in red and yellow brick;[19] and Stone Gate Lodge, at Beckford's western entrance, in the same brick style.[20]

Ornamental stonework also survives in the grounds of the former mansion. Two groups of four statues, representing the four seasons and the four elements, stand among trees southeast of the site; they are thought to have been bought by the Marquess at the Paris Exhibition of 1855 or 1867.[21][22] To the northwest, close to the site of Beckford's abbey, are three decorated urns on plinths, said to be from the same source.[23]

Notes

- For a short, comprehensive historical account see Wilton-Ely, J. (1980). "The Genesis and Evolution of Fonthill Abbey". Architectural History. 23: 40–51. doi:10.2307/1568421. JSTOR 1568421. S2CID 195035413.

- For more in-depth accounts see Brockman, H. A. N., (1956), The Caliph of Fonthill, London: Werner Laurie, or Fothergill, B. (1979), Beckford of Fonthill, London: Faber and Faber)

- Dakers, Caroline, ed. (2018). Fonthill Recovered – A cultural history. London: UCL Press. pp. All Chap 4, 'The Beckford Era', pp. 59–93.

- UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- Oliver, J. W. (1932), The Life of William Beckford, London: Oxford University Press – Humprhey Milford, pp. 100 & 203.

- Brian Fothergill, Beckford of Fonthill, London: Faber and Faber, 1979, pp. 169–170.

- Aldrich, Megan (1994). Gothic Revival. London: Phaidon Press Limited. p. 79. ISBN 0714828866.

- Dale, Anthony, James Wyatt: Architect 1746–1813, see the chapter entitled "Character"

- Brockman, The Caliph of Fonthill, p. 63.

- Wilton-Ely, p. 48

- Historic England. "Remains of Old Fonthill Abbey (1146090)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

- "Ghosts of Fonthill". unbound.com. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- "Tisbury Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Plan" (PDF). Wiltshire Council. February 2009. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus; Cherry, Bridget (revision) (1975) [1963]. Wiltshire. The Buildings of England (2nd ed.). Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. p. 248. ISBN 978-0-14-0710-26-7.

- Freeman, Jane; Stevenson, Janet H. (1987). Crowley, D. A. (ed.). "Victoria County History: Wiltshire: Vol 13, pp. 155–169 – Fonthill Gifford". British History Online. University of London. Retrieved 4 November 2016.

- Historic England. "Fonthill landscape park (1000322)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 11 November 2016.

- Historic England. "Tisbury Lodge with gates and gate piers (1300419)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 11 November 2016.

- Historic England. "Lawn Lodge (1318781)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 11 November 2016.

- Historic England. "West Gate Lodge (1146010)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 11 November 2016.

- Historic England. "Stone Gate Lodge (1146091)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 11 November 2016.

- Historic England. "Group of 4 statues of the Four Seasons (1146089)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 11 November 2016.

- Historic England. "Group of 4 statues of the Four Elements (1183802)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 11 November 2016.

- Historic England. "Three urns on the site of Old Fonthill Abbey (1183814)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 11 November 2016.

References

- Beckford, William. (2007), Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 8 February 2007, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

Further reading

- Ostergard, Derek E., ed. (2001). William Beckford 1760–1844: An Eye for the Magnificent. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-09068-0.

- Simon Thurley (2004). Lost buildings of Britain. Viking. pp. 41 et seq. ISBN 9780670915217. – accompanying the Channel 4 television series

External links

- "Fonthill History". The Fonthill Estate. Archived from the original on 5 January 2017. Retrieved 11 November 2016.

- The Fonthill Abbey section of a Beckfordiana website – includes an illustrated 1823 guidebook

- 1859–1860 – Fonthill Abbey, Tisbury, Wiltshire at pulham.org.uk – about landscaping work by James Pulham and Son

- Incomplete 3D model of Fonthill Abbey at hvtesla.com (2010)

- Digital reconstruction of Fonthill Abbey Archived 14 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine at fonthillabbey.org – includes virtual reality game (2017)