Bed management in England

Bed management is the allocation and provision of beds, especially in a hospital where beds in specialist wards are a scarce resource.[2] The "bed" in this context represents not simply a place for the patient to sleep, but the services that go with being cared for by the medical facility: admission processing, physician time, nursing care, necessary diagnostic work, appropriate treatment, food, cleaning and so forth.

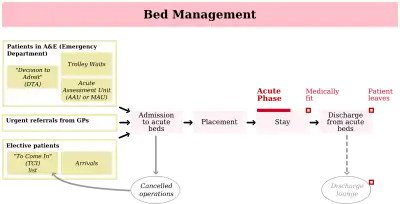

In the UK, acute hospital bed management is usually performed by a dedicated team and may form part of a larger process of patient flow management; a bed manager may be part of such a team.

Importance

Because hospital beds are economically scarce resources, there is naturally pressure to ensure high occupancy rates and therefore a minimal buffer of empty beds. However, because the volume of emergency admissions is unpredictable, hospitals with average occupancy levels above 85 per cent "can expect to have regular bed shortages and periodic bed crises."[3][4] In the first quarter of 2017 average overnight occupancy in English hospitals was 91.4%.[5]

Shortage of beds can result in cancellations of admissions for planned (elective) surgery, admission to inappropriate wards (medical vs. surgical, male vs. female etc.), delay admitting emergency patients,[6] and transfers of existing inpatients between wards, which "will add a day to a patient's length of stay".[1]

These can be politically sensitive issues in publicly funded healthcare systems. In the UK there has been concern over inaccurate and sometimes fraudulently manipulated waiting list statistics,[7] and claims that "the current A&E target is simply not achievable without the employment of dubious management tactics."[8] In 2013 two Stafford Hospital nurses were struck off the nursing register for falsifying A&E discharge times between 2000 and 2010 to avoid breaches of four-hour waiting targets.[9]

In 2018 NHS England started a new initiative to reduce the number of what it now called "stranded" or "super stranded" patients, super stranded being people in hospital for more 20 days. About 18,000 of the 101,259 acute and general beds in English NHS hospitals were occupied by "super stranded" patients in May 2018. By August 2018 2,338 of these beds had been freed. Some of the delays were related to social care, but more related to the management of inpatient stays.[10]

In February 2019, NHS Scotland calculated that 1,419 people had their discharge from hospital delayed in that month, most commonly for health and social care reasons. 1,122 were delayed more than three days. Between them they had spent 40,813 days in hospital.[11]

Specific problems

- Shortage of beds due to lack of other options. Hospitals in developed countries cannot force a patient to leave if the patient's home is reasonably believed to be unsafe. For example, if a frail, elderly patient has recovered from an acute illness, but is unable to dress himself and prepare simple meals on his own, then the hospital must ensure that the patient will have sufficient assistance with these necessary activities of daily living, or the patient must remain in the hospital. In places with a shortage of skilled nursing facilities, home health care workers, and related support organizations, beds may be unavailable for new, acutely sick patients because of the continued presence of the previous patients. This is sometimes known as a "bed blocking".[12]

- False appearance or unnecessary creation of a bed shortage. "Bed hiding", as it is sometimes called, is the practice of delaying admissions due to a falsely claimed lack of beds in the appropriate department.[13] Bed hiding has several causes, including scheduling so many elective procedures that there are inadequate beds left for emergency admissions; frequent changes from ward to ward; inadequate communication, so that cleaning staff don't know when a bed has become available and needs cleaning; misalignment of tasks, so that skilled nurses are expected to take time away from direct patient care to clean beds; too few nurses scheduled for a shift; and overworked staff, who may be inclined to mis-report a bed as full, especially at the end of a shift, in an effort to shift the workload to another person.[14][15] Bed hiding can be significantly reduced by careful tracking of bed status, making cleaning after discharge the top priority for cleaning staff, and even by physically moving patients to the ward as soon as they are ready for admission rather than boarding them in the emergency department. Reducing bed hiding in regular wards can reduce wait times in the emergency department.

Causal factors

Patients who are medically fit to leave may be delayed by many factors. Delays due to the lack of social care provision, care homes and residential care have received considerable publicity.

In the month of April 2019 there were 130,800 total delayed days in English NHS hospitals, a reduction from 145,300 delayed days in April 2018. The proportion attributed to social care decreased to 27.4%, compared to 30.7% in March 2018. 31.7% of the social care delays were patients awaiting a care package in their own home. 6,354 delayed days were patients awaiting the completion of a social care assessment and 9,251 days related to patients awaiting spaces in residential homes. Other delays may be attributable to issues within the hospital, such as delays in arranging medication or completing tests.[16]

Further reading

- "Bed management: Review of national findings" (PDF). Audit Commission. 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 February 2014.

- Department of Health (2004). "Faster access: Bed management demand and discharge predictors". Archived from the original on 6 January 2012.

- Inpatient admissions and bed management in NHS acute hospitals. 24 February 2000. ISBN 0105566748. Archived from the original on 14 April 2013. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- Day, Christopher (1985) From Figures to Facts. London: the King's Fund ISBN 0-19-724627-3; pp. 43–50 & 123-130 &c

References

- Proudlove NC, Gordon K, Boaden R (March 2003). "Can good bed management solve the overcrowding in accident and emergency departments?". Emerg Med J. 20 (2): 149–55. doi:10.1136/emj.20.2.149. PMC 1726041. PMID 12642528.

- Boaden, Ruth; Nathan Proudlove; Melanie Wilson (1999). "An exploratory study of bed management". Journal of Management in Medicine. 13 (4): 234–50. doi:10.1108/02689239910292945. ISSN 0268-9235. PMID 10787495.

- "Inpatient Admissions and Bed management in NHS acute hospitals". National Audit Office. 21 February 2000. p. 7. Retrieved 20 May 2008.

- NHS reforms by the coalition government and bed management technology

- "Bed occupancy rate hits record high in first quarter of 2017". Health Care Leader. 26 May 2017. Archived from the original on 14 April 2018. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- "Patient Experience". Bed management: Review of National Findings. Audit Commission. 19 June 2003. Retrieved 20 May 2008.

- "The NHS: Has the Additional Funding Worked?". Civitas. April 2005. pp. 2–3. Archived from the original on 28 August 2008. Retrieved 20 May 2008.

- Mayhew, Les; Smith, David (December 2006). Latest research statistically proves A&E waiting times are not being met (PDF). ISBN 978-1-905752-06-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 January 2011. Retrieved 20 May 2008.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - "Stafford nurses struck off over waiting times". BBC News Online. 5 July 2013.

- "Performance Watch: Exclusive figures lay bare hospitals' capacity challenge". Health Service Journal. 25 October 2018. Retrieved 1 December 2018.

- "Social care hold-ups blamed for 9% rise in bed-blocking". Home Care Insight. 3 April 2019. Retrieved 13 May 2019.

- Bed blocking threat to A&E unit and Bed blocking, from the BBC

- Patients Wait for Hours in Hallways; Strain Felt Throughout State New Haven Register, April 16, 2006.

- How hospitals are killing E.R. patients at Slate.com

- Psychiatric boarding at U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

- "Bed blocking cases drop by 10% in England, NHS data reveals". Homecare Insight. 12 July 2019. Retrieved 25 August 2019.