Behaviour support systems review

A behaviour support systems review is the process of gathering data, examining and reporting on the capability and capacity of a service system or a service organisation to deliver positive behaviour support to people with an intellectual disability,[1] general learning disability, or generalized neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by significantly impaired adaptive functioning.[2]

Key reasons for undertaking periodic reviews is to ensure the service system continues to meet the functional and therapeutic needs of clients in their care, support continuous improvement efforts and importantly, respond to the fact that even when positive behaviour support plans are well designed and technically sound, they may be poorly implemented, not adhered to over time or suffer from misaligned or inadequate service factors.[3] This is particularly important given a great deal of effort is usually expended in developing and maintaining behaviour support programs[4] to modify any individual's maladaptive behaviours.

There is a growing body of literature regarding the proficient implementation of and adherence to behaviour support plans which stress the importance of service factors such as staff training, staff attitudes, resource availability, quality of communications, staff matching, supervision, access to specialist clinicians, etc.[5][6] Understanding the impact of these factors is an important step in the overall quality improvement and maintenance strategy of any service system.[7][8]

A number of tools assist the review process including: Dr. Gary LaVigna’s, The Periodic Service Review: A Total Quality Assurance System for Human Services and Education[9] and Dr. Jack Dikian’s, The clinical audit of behaviour support systems manual: for agencies that support people with intellectual disability[10]

Context

The term behaviour support system is used to describe the policies, processes, tools, people and other factors as well as the interactions between these as they relate to the provision of behaviour support.[7] The scope of this kind of review is usually limited to those elements that have, or may have, an impact on the manner behaviour supports are provided rather than a documented evaluation of whether or not an organisation is financially and materially viable.[11]

A behaviour support systems review is similar to an audit in that it is a professional and independent examination of a service system's activities in the narrow domain of behaviour support services. Like an audit, these reviews examine activities in the light of available policies, procedures and generally accepted good clinical practice. Audit processes, however, rely heavily on well-established conventions and generally accepted operating principles and quantitative standards quantitative analysis to provide the basis for assessment.[12]

Approach

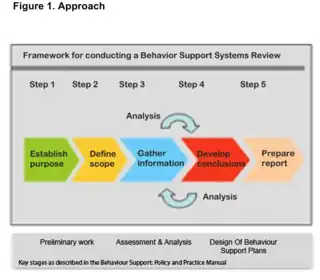

Whilst the general approach to undertaking these reviews seem (see Figure 1) to follow a sequential methodology, in reality some of these steps can and often do overlap. For instance, when establishing the purpose of the Review (step 1) it might be convenient and logical to commence defining the scope of the work. In addition, steps 3 and 4 are carried out in an iterative manner. Whilst information is being gathered, early conclusions may be formed. This in turn may prompt the reviewer to seek further detail in order to support or dispel any conclusion.

Using an iterative method to gather and examine data allows for the generation of progressively “better” impressions of issues, and in turn, improves the conclusions reached and recommendations made. It may be that a number of iterations or passes is required to gain the required detail, evidence and understanding. Subsequent interviews become more and more focused on validation of ideas and conclusions formed.

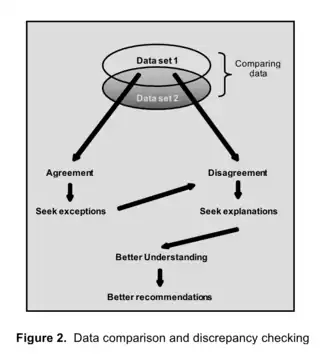

Constant comparison [13] of gathered information (see Fig 2) is key to this process. Information gathered from one group of staff (for example) can be compared with information gathered from another. Information can be compared with stated expectations of the Service System as well as good practice in behaviour support. Information comparison can result in exceptions or mismatches requiring the reviewer to seek further clarification.

Service and systemic factors

Service factors

Service factors describe all the operational and procedural components in a Service System that may have an impact on behaviour support delivery. These include such things as policies, procedures, processes, tools, people, knowledge, skills, etc. A more comprehensive list of service factors can be found in the further reading section below.

1. Behaviour support[14]

The Service System understands the role of behaviour support practices and takes responsibility to provide the best possible behaviour support it can to its clients. This is done through suitable use of Person-centred planning, assessment, design, implementation and monitoring of support plans, as well as ensuring availability of suitably trained staff and resources.

2. Policy, processes and procedures

The Service System has policies and procedures that guide the provision of behaviour support.

3. Knowledge, experience and staff development The Service System places emphasis on ensuring that staff have the relevant skills to perform the necessary behaviour support duties through training, mentoring and supervision.

4. Team values and beliefs

The Service System encourages and promotes positive behaviour support principles as well as ensuring that values and attitudes held by staff and management promote the norms and patterns of everyday life which are valued in the general community as far as is possible.

5. Staff stressors

The Service System recognises how engagement with behaviour support processes and programs can be hampered by work-related stressors experienced by staff and takes measures to reduce and manage work-related staff stressors.

6. Routines and meaningful engagement

The Service System ensures that clients routines are supportive of individual needs and preferences and are implemented in a consistent manner.

7. Cohesiveness and level of collaboration between service providers

The services involved in the client's life work in a cooperative and integrated manner to ensure consistency of support and care across all settings.

Systemic factors

Systemic theory or systems theory is a body of knowledge that has arisen out of the observations of clinical and counselling psychologists as they work with individuals and their families.[3] The key idea is the acknowledgement that individuals cannot be understood in isolation from one another. Families and services are systems of interconnected and interdependent individuals none of whom can be understood in isolation from the family or Service System.[15] Systemic factors can include

1.Systemic empathy and focus[3]

The Service System seeks to understand client behaviours, as well as barriers and solutions to interventions from a systemic point of view. The Service System acknowledges that patterns of behaviour can develop within staff and management as a consequence of client behaviours and these become repetitive, circular and evolve over time.

2. Blame, labelling or judgement of clients.[16]

The Service System takes a client centred perspective and does not engage in blaming or labelling the Service User. Labelling may include pathologising, criminalising, etc.

3. Power differentials .[17]

Key parties in the Service System exercise their authority in ways that contribute positively to the provision of behaviour support. The service ensures that this does not hinder or prevent all staff members from contributing to behaviour support planning and implementation.

A more comprehensive can be found in the further reading section below.

Forming conclusions and recommendations

The research method developed by grounded theory[18][19] provides a useful model for the process of developing conclusions and themes based on the information gathered in Step 3. This approach sets out to find what set of hypotheses account for the current situation within the Service System as they emerge from the collected information.

Themes[20] Thematic analysis springs from conclusions which in turn arise from collected data that can be supported by evidence. The reviewer may look for evidence to support a statement that has been made. For example, behavioural incidents recorded through the use of antecedent, behaviour and consequence charts[21] may support a statement about change in the number of incidences relating to a client's service challenging behaviour.

When presenting recommendations, it is important to consider how the service system might perceive them. Recommendations should be made as suggestions rather than directives and provide the service system the flexibility over how they choose to implement them. It may be appropriate to frame recommendations as extensions to work the Service System has already commenced. Importantly, note that some recommendations may be in response to findings associated with more global issues such as those spanning an entire region, organisation or department.

References

- American Psychiatric Association (2013). "Highlights of Changes from DSM-IV to DSM-5". Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. p. 809. doi:10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596. hdl:2027.42/138395. ISBN 978-0-89042-555-8.

- Harrison, Patti. (August 2015). "Research with Adaptive Behavior Scales". The Journal of Special Education. 1 (9995): 743–800. doi:10.1177/002246698702100108. PMC 4561509. PMID 26063472.

- Rhodes, Paul; Donelly, Michelle; Whatson, Lesely; Dikian, Jack; Hansson, Andres; Mora, Lucinda (June 2012). "Systemic hypothesising for challenging behaviour in intellectual disabilities: a reflecting team approach". Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy.

- Applied Behavior Analysis for Teachers. Merrill. 2010. ISBN 9780130797605.

- Lowe, Kathy; Jones, Edwin; Allen, David; Davies, Dee; James, Wendy; Doyle, Tony (December 2006). "Staff Training in Positive Behaviour Support: Impact on Attitudes and Knowledge". Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disability.

- Webber, Lynne; McVilly, Keith; Fester, Tarryn; Chan, Jeffrey (2011). "Factors influencing quality of behaviour support plans and the impact of plan quality on restrictive intervention use". International Journal of Positive Behavioural Support.

- "Behaviour support systems review practice guide, Jack Dikian". Academia. 25 February 2014. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- La Vigna (1994). The Periodic Service Review: A Total Quality Assurance System for Human Services and Education. Brookes Publishing. ISBN 1557661421.

- LaVigna, Gary. (1994). The Periodic Service Review: A Total Quality Assurance System for Human Services and Education. USA: Brookes Publishing.

- Dikian, Jack. (2017). The Clinical Audit of Behaviour Support Systems Manual: for agencies that support people with intellectual disability. Sydney Australia: Amazon Publishing..

- Arens, Elder, Beasley; Auditing and Assurance Services; 14th Edition; Prentice Hall; 2012

- "Auditing Standard No. 5". pcaobus.org. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- "What is Constant Comparative Method?". Delve. 25 February 2014. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- Dillenburger K, Keenan M (June 2009). "None of the As in ABA stand for autism: dispelling the myths". Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability. 34 (2): 193–195. doi:10.1080/13668250902845244. PMID 19404840. S2CID 1818966.

- Jolly, W.; Froom, J.; Rosen, M. G. (1980). "The genogram". The Journal of Family Practice. 10 (2): 251–255. PMID 7354276.

- Malle, Bertram; Guglielmo, Steve; Monroe, Andrew (June 2014). "A Theory of Blame". Psychological Inquiry. 25 (2): 147–186. doi:10.1080/1047840X.2014.877340.

- Sachdev, Itesh; Bourhis, Richard (December 1985). "Social categorization and power differentials in group relations". European Journal of Social Psychology. 15 (4): 415–434. doi:10.1002/ejsp.2420150405.

- Glaser, Barney G.; Strauss, Anselm L. (2017). The Discovery of Grounded Theory. doi:10.4324/9780203793206. ISBN 9780203793206.

- Thomas, G.; James, D (2006). "Reinventing grounded theory: some questions about theory, ground and discovery". British Educational Research Journal. 32 (6): 767–795. doi:10.1080/01411920600989412. JSTOR 30032707. S2CID 44250223.

- Braun, Virginia; Clarke, Victoria (2006). "Using thematic analysis in psychology". Qualitative Research in Psychology. 3 (2): 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. S2CID 10075179.

- Pelios L, Morren J, Tesch D, Axelrod S (1999). "The impact of functional analysis methodology on treatment choice for self-injurious and aggressive behavior". Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 32 (2): 185–195. doi:10.1901/jaba.1999.32-185. PMC 1284177. PMID 10396771.

Further reading

- LaVigna, Gary; Willis, Thomas (1994). The Periodic Service Review: A Total Quality Assurance System for Human Services and Education. USA: Brookes Publishing. ISBN 1557661421.

- Dikian, Jack (2017). The clinical audit of behaviour support systems manual: for agencies that support people with intellectual disability. Sydney, Australia: Amazon. ASIN B07BSXBH9N.