Bell UH-1 Iroquois

The Bell UH-1 Iroquois (nicknamed "Huey") is a utility military helicopter designed and produced by the American aerospace company Bell Helicopter. It is the first member of the prolific Huey family, as well as the first turbine-powered helicopter in service with the United States military.

| UH-1 Iroquois / "Huey" | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

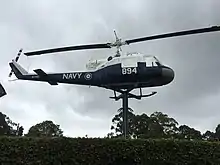

| A Bell UH-1H Iroquois | |

| Role | Utility helicopter |

| National origin | United States |

| Manufacturer | Bell Helicopter |

| First flight | 20 October 1956 (XH-40) |

| Introduction | 1959 |

| Status | In service |

| Primary users | United States Army (historical) Japan Ground Self-Defense Force Australian Army (historical) See Operators section for others |

| Produced | 1956–1987 |

| Number built | >16,000 |

| Variants | Bell UH-1N Twin Huey Bell 204/205 Bell 212 |

| Developed into | Bell AH-1 Cobra Bell 214 |

Development of the Iroquois started in the early 1950s, a major impetus being a requirement issued by the United States Army for a new medical evacuation and utility helicopter. The Bell 204, first flown on 20 October 1956, was warmly received, particularly for the performance of its single turboshaft engine over piston engine-powered counterparts. An initial production contract for 100 HU-1As was issued in March 1960. In response to criticisms over the rotorcraft's power, Bell quickly developed multiple models furnished with more powerful engines; in comparison to the prototype's Lycoming YT53-L-1 (LTC1B-1) engine, producing 700 shp (520 kW), by 1966, the Lycoming T53-L-13, capable of 1,400 shp (1,000 kW), was being installed on some models. A stretched version of the Iroquois, first flown during August 1961, was also produced in response to Army demands for a version than could accommodate more troops. Further modifications would include the use of all-aluminum construction, the adoption of a rotor brake, and alternative powerplants.

The Iroquois was first used in combat operations during the Vietnam War, the first examples being deployed in March 1962. It was used for various purposes, conducting general support, air assault, cargo transport, aeromedical evacuation, search and rescue, electronic warfare, and ground attack missions. Armed Iroquois gunships carried a variety of weapons, including rockets, grenade launchers, and machine guns, and were often modified in the field to suit specific operations. The United States Air Force deployed its Iroquois to Vietnam, using them to conduct reconnaissance operations, psychological warfare, and other support roles. Other nations' armed air services, such as the Royal Australian Air Force, also dispatched their own Iroquois to Vietnam. In total, around 7,000 Iroquois were deployed in the Vietnam theatre, over 3,300 of which were believed to be destroyed. Various other conflicts have seen combat deployments of the Iroquois, such as the Rhodesian Bush War, Falklands War, War in Afghanistan, and the 2007 Lebanon conflict.

The Iroquois was originally designated HU-1, hence the Huey nickname, which has remained in common use, despite the official redesignation to UH-1 in 1962.[1] Various derivatives and developments of the Iroquois were produced. A dedicated attack helicopter, the Bell AH-1 Cobra, was derived from the UH-1, and retained a high degree of commonality. The Bell 204 and 205 are Iroquois versions developed for the civilian market. In response to demands from some customers, a twin-engined model, the UH-1N Twin Huey, was also developed during the late 1960s; a four-bladed derivative, the Bell UH-1Y Venom, was also developed during the early twenty-first century. In US Army service, the Iroquois was gradually phased out following the introduction of the Sikorsky UH-60 Black Hawk and the Eurocopter UH-72 Lakota, although hundreds were still in use more than 50 years following the type's introduction. In excess of 16,000 Iroquois have been built since 1960.[2]

Development

In 1952, the U.S. Army identified a requirement for a new helicopter to serve as medical evacuation (MEDEVAC), instrument trainer, and general utility aircraft. The Army determined that current helicopters were too large, underpowered, or too complex to maintain easily. During November 1953, revised military requirements were submitted to the Department of the Army.[3] Twenty companies submitted designs in their bid for the contract, including Bell Helicopter with the Model 204 and Kaman Aircraft with a turbine-powered version of the H-43.[4] On 23 February 1955, the Army announced its decision, selecting Bell to build three copies of the Model 204 for evaluation with the designation XH-40.[5]

Model 204

Powered by a prototype Lycoming YT53-L-1 (LTC1B-1) engine producing 700 shp (520 kW), the XH-40 first flew on 20 October 1956,[6] at Fort Worth, Texas, with Bell's chief test pilot, Floyd Carlson, at the controls. Even prior to the first flight, the Army had placed an order for six YH-40 service test helicopters. During 1957, a further two prototypes were completed.[3][7] In 1959, the Army awarded Bell a production contract for 182 aircraft, which was designated "HU-1A" and officially named Iroquois after the Native American nations.[8]

The helicopter quickly developed a nickname derived from its HU-1 designation, which came to be pronounced as "Huey". The reference became so popular that Bell began casting the name on the helicopter's anti-torque pedals.[1] The official U.S. Army name was almost never used in practice.[9] Even after September 1962, at which point the designation for all models was changed to UH-1 under a unified Department of Defense (DOD) designation system, yet the nickname persisted.[4]

While glowing in praise for the helicopter's advances over piston-engined helicopters, the Army reports from the service tests of the YH-40 found it to be underpowered with the production T53-L-1A powerplant producing a maximum continuous 770 shaft horsepower (570 kilowatts).[N 1] The Army indicated the need for improved follow-on models even as the first UH-1As were being delivered. In response, Bell proposed the UH-1B, equipped with the Lycoming T53-L-5 engine producing 960 shp (720 kW) and a longer cabin that could accommodate either seven passengers or four stretchers and a medical attendant. Army testing of the UH-1B started in November 1960, with the first production aircraft delivered in March 1961.[3]

Bell commenced development of the UH-1C in 1960 in order to correct aerodynamic deficiencies of the armed UH-1B. Bell fitted the UH-1C with a 1,100 shp (820 kW) T53-L-11 engine to provide the power needed to lift all weapons systems in use or under development. The Army eventually refitted all UH-1B aircraft with the same engine. A new rotor system was developed for the UH-1C to allow higher air speeds and reduce the incidence of retreating blade stall during diving engagements. The improved rotor resulted in better maneuverability and a slight speed increase.[7] The increased power and a larger diameter rotor required Bell's engineers to design a new tail boom for the UH-1C. The longer tail boom incorporated a wider chord vertical fin on the tail rotor pylon and larger synchronized elevators.

Bell also introduced a dual hydraulic control system for redundancy as well as an improved inlet filter system for the dusty conditions found in southeast Asia. The UH-1C fuel capacity was increased to 242 US gallons (920 liters), and gross weight was raised to 9,500 lb (4,309 kg), giving a nominal useful load of 4,673 lb (2,120 kg). UH-1C production started in June 1966 with a total of 766 aircraft produced, including five for the Royal Australian Navy and five for Norway.

Model 205

_%22N205SD%22.jpg.webp)

While earlier short-body Hueys were a success, the Army wanted a version that could carry more troops. Bell's solution was to stretch the HU-1B fuselage by 41 in (104 cm) and use the extra space to fit four seats next to the transmission, facing out. Seating capacity increased to 15, including crew.[10] The enlarged cabin could also accommodate six stretchers and a medic, two more than the earlier models.[10] In place of the earlier model's sliding side doors with a single window, larger doors were fitted which had two windows, plus a small hinged panel with an optional window, providing enhanced access to the cabin. The doors and hinged panels were quickly removable, allowing the Huey to be flown in a doors off configuration.

The Model 205 prototype flew on 16 August 1961.[11][12] Seven pre-production/prototype aircraft had been delivered for testing at Edwards AFB starting in March 1961. The 205 was initially equipped with a 44-foot (13.4 m) main rotor and a Lycoming T53-L-9 engine with 1,100 shp (820 kW). The rotor was lengthened to 48 feet (14.6 m) with a chord of 21 in (53 cm). The tailboom was also lengthened, in order to accommodate the longer rotor blades. Altogether, the modifications resulted in a gross weight capacity of 9,500 lb (4,309 kg). The Army ordered production of the 205 in 1963, produced with a T53-L-11 engine for its multi-fuel capability.[N 2][13] The prototypes were designated as YUH-1D and the production aircraft was designated as the UH-1D.

During 1966, Bell installed the 1,400 shp (1,000 kW) Lycoming T53-L-13 engine to provide more power for the helicopter. The pitot tube was relocated from the nose to the roof of the cockpit to prevent damage during landing. Production models in this configuration were designated as the UH-1H.[9][14]

Marine Corps

In 1962, the United States Marine Corps held a competition to choose an assault support helicopter to replace the Cessna O-1 fixed-wing aircraft and the Kaman OH-43D helicopter. The winner was the UH-1B, which was already in service with the Army. The helicopter was designated the UH-1E and modified to meet Marine requirements. The major changes included the use of all-aluminum construction for corrosion resistance,[N 3] radios compatible with Marine Corps ground frequencies, a rotor brake for shipboard use to stop the rotor quickly on shutdown and a roof-mounted rescue hoist.

The UH-1E was first flown on 7 October 1963, and deliveries commenced on 21 February 1964; a total of 192 Iroquois of this model were completed.[4] Due to production line realities at Bell, the UH-1E was produced in two different versions, both with the same UH-1E designation. The first 34 built were essentially UH-1B airframes with the Lycoming T53-L-11 engine producing 1,100 shp (820 kW). When Bell switched production to the UH-1C, the UH-1E production benefited from the same changes. The Marine Corps later upgraded UH-1E engines to the Lycoming T53-L-13, which produced 1,400 shp (1,000 kW), after the Army introduced the UH-1M and upgraded their UH-1C helicopters to the same engine.

Air Force

The United States Air Force (USAF) held a competition for a helicopter to be used for support on missile bases included a specific requirement to mandate the use of the General Electric T58 turboshaft as a powerplant. The Air Force had a large inventory of these engines on hand for its fleet of HH-3 Jolly Green Giant rescue helicopters and using the same engine for both helicopters would save costs. In response, Bell proposed an upgraded version of the 204B with the T58 engine. Because the T58 output shaft is at the rear, and was thus mounted in front of the transmission on the HH-3, it had to have a separate offset gearbox (SDG or speed decreaser gearbox) at the rear, and shafting to couple to the UH-1 transmission.[15]

Twin-engine variants

The single-engine UH-1 variants were followed by the twin-engine UH-1N Twin Huey and years later the UH-1Y Venom.[4] Bell began development of the UH-1N for Canada in 1968. It changed to the more powerful Pratt & Whitney Canada PT6T twin-engine set. The US also ordered the helicopter with the USAF receiving it in 1970. Canada's military, the U.S. Marine Corps, and the U.S. Navy first received the model in 1971.[16][4]

In 1996, the USMC launched the H-1 upgrade program via the award of a contract to Bell Helicopter for development of the improved UH-1Y and AH-1Zs variants.[17][18] The UH-1Y includes a lengthened cabin, four-blade rotor, and two more powerful GE T700 engines.[2] The UH-1Y entered service with the USMC in 2008.[19]

Design

The Bell UH-1 Iroquois is a utility helicopter designed for military use. It has a metal fuselage of semi-monocoque construction with tubular landing skids and two rotor blades on the main rotor.[20] Early UH-1 models featured a single Lycoming T53 turboshaft engine in versions with power ratings from 700 shp (522 kW) to 1,400 shp (1,040 kW).[7] Later UH-1 and related models often featured twin engines and four-blade rotors.[4] All members of the UH-1 family have similar construction. The UH-1H is the most-produced version, and is representative of all types. The main structure consists of two longitudinal main beams that run under the passenger cabin to the nose and back to the tail boom attachment point. The main beams are separated by transverse bulkheads and provide the supporting structure for the cabin, landing gear, under-floor fuel tanks, transmission, engine and tail boom. The main beams are joined at the lift beam, a short aluminum girder structure that is attached to the transmission via a lift link on the top and the cargo hook on the bottom and is located at the aircraft's center of gravity. The lift beams were changed to steel later in the UH-1H's life, due to cracking on high-time airframes. The semi-monocoque tail boom attaches to the fuselage with four bolts.[21]

The UH-1H's dynamic components include the engine, transmission, rotor mast, main rotor blades, tail rotor driveshaft, and the 42-degree and 90-degree gearboxes of the tail rotor. The main rotor transmission consists of a 90 degree bevel gear assembly with a reduction ratio of 2.14:1, followed by a 2-stage planetary gearset with a ratio of 9.53:1 (two stages of 3.087:1 each). This is in addition to the output gearbox of the T53 engine with a reduction ratio of 3.19:1. This combined reduction results in 324 rpm at the main rotor.[22] The two-bladed, semi-rigid rotor design, with pre-coned and underslung blades,[23]: 129 is a development of early Bell model designs, such as the Bell 47 with which it shares common design features, including a damped stabilizer bar. The two-bladed system reduces storage space required for the aircraft, but at a cost of higher vibration levels. The two-bladed design is also responsible for the characteristic 'Huey thump' when the aircraft is in flight, which is particularly evident during descent and in turning flight. The tail rotor is driven from the main transmission, via the two directional gearboxes which provide a tail rotor speed approximately six times that of the main rotor to increase tail rotor effectiveness.[21]

The UH-1H also features a synchronized elevator on the tail boom, which is linked to the cyclic control and allows a wider center of gravity range. The standard fuel system consists of five interconnected fuel tanks, three of which are mounted behind the transmission and two of which are under the cabin floor. The landing gear consists of two arched cross tubes joining the skid tubes. The skids have replaceable sacrificial skid shoes to prevent wear of the skid tubes themselves. Skis and inflatable floats may be fitted.[21] While the five main fuel tanks are self-sealing, the UH-1H was not equipped with factory armor, although armored pilot seats were available.[21]

Internal seating is made up of two pilot seats and additional seating for up to 13 passengers or crew in the cabin. The maximum seating arrangement consists of a four-man bench seat facing rearwards behind the pilot seats, facing a five-man bench seat in front of the transmission structure, with two, two-man bench seats facing outwards from the transmission structure on either side of the aircraft. All passenger seats are constructed of aluminum tube frames with canvas material seats, and are quickly removable and reconfigurable. The cabin may also be configured with up to six stretchers, an internal rescue hoist, auxiliary fuel tanks, spotlights, or many other mission kits. Access to the cabin is via two aft-sliding doors and two small, forward-hinged panels. The doors and hinged panels may be removed for flight or the doors may be pinned open. Pilot access is via individual hinged doors.[21]

The UH-1H's dual controls are conventional for a helicopter and consist of a single hydraulic system boosting the cyclic stick, collective lever and anti-torque pedals. The collective levers have integral throttles, although these are not used to control rotor rpm, which is automatically governed, but are used for starting and shutting down the engine. The cyclic and collective control the main rotor pitch through push-pull tube linkages to the swashplate, while the anti-torque pedals change the pitch of the tail rotor via a tensioned cable arrangement. Some UH-1Hs have been modified to replace the tail rotor control cables with push-pull tubes similar to the UH-1N Twin Huey.[21]

Operational history

U.S. Army

The HU-1A (later redesignated UH-1A) first entered service with the 101st Airborne Division at Fort Campbell, Kentucky, the 82nd Airborne Division, and the 57th Medical Detachment. Although intended for evaluation only, the Army quickly pressed the new helicopter into operational service, and Hueys with the 57th Medical Detachment arrived in Vietnam in March 1962.[14][4] The UH-1 has long been a symbol of US involvement in Southeast Asia in general and Vietnam in particular, and as a result of that conflict, has become one of the world's most recognized helicopters. In Vietnam primary missions included general support, air assault, cargo transport, aeromedical evacuation, search and rescue, electronic warfare, and later, ground attack. During the conflict, the craft was upgraded, notably to a larger version based on the Model 205. This version was initially designated the UH-1D and flew operationally from 1963.

During its Vietnam War service, the UH-1 was used for various purposes and various terms for each task abounded. UH-1s tasked with ground attack or armed escort were outfitted with rocket launchers, grenade launchers, and machine guns. As early as 1962, UH-1s were modified locally by the companies themselves, who fabricated their own mounting systems.[24] These gunship UH-1s were commonly referred to as "Frogs" or "Hogs" if they carried rockets, and "Cobras" or simply "Guns" if they had guns.[25][26][N 4][27] UH-1s tasked and configured for troop transport were often called "Slicks" due to an absence of weapons pods. Slicks did have door gunners, but were generally employed in the troop transport and medevac roles.[9][14]

UH-1s also flew hunter-killer teams with observation helicopters, namely the Bell OH-58A Kiowa and the Hughes OH-6 Cayuse (Loach).[9][14] Towards the end of the conflict, the UH-1 was tested with TOW missiles, and two UH-1B helicopters equipped with the XM26 Armament Subsystem were deployed to help counter the 1972 Easter Invasion.[28] USAF Lieutenant James P. Fleming piloted a UH-1F on a 26 November 1968 mission that earned him the Medal of Honor.[29]

During the course of the conflict, the UH-1 went through several upgrades. The UH-1A, B, and C models (short fuselage, Bell 204) and the UH-1D and H models (stretched-fuselage, Bell 205) each had improved performance and load-carrying capabilities. The UH-1B and C performed the gunship, and some of the transport, duties in the early years of the Vietnam War. UH-1B/C gunships were replaced by the new AH-1 Cobra attack helicopter from 1967 to late 1968. The increasing intensity and sophistication of NVA anti-aircraft defenses made continued use of UH-1 gunships impractical, and after Vietnam the Cobra was adopted as the Army's main attack helicopter. Devotees of the UH-1 in the gunship role cite its ability to act as an impromptu Dustoff if the need arose, as well as the superior observational capabilities of the larger Huey cockpit, which allowed return fire from door gunners to the rear and sides of the aircraft.[9][14] In air cavalry troops (i.e., companies) UH-1s were combined with infantry scouts, OH-6 and OH-58 aero-scout helicopters, and AH-1 attack helicopters to form several color-coded teams (viz., blue, white, red, purple, and pink) to perform various reconnaissance, security, and economy of force missions in fulfilling the traditional cavalry battlefield role.

_at_anchor_in_the_Mekong_Delta_ca_late_1960s.jpg.webp)

The Army tested a great variety of experimental weapons on the UH-1; nearly anything that could be carried. The Army desired weapons with large calibers and high rates of fire, which led to the testing of a 20 mm cannon on a large mount bolted to the cabin floor. The size of the weapon allowed very little room for movement. The Army further tested a full-size Vulcan cannon firing out the door of a UH-1. It was capable of firing 2400 rounds per minute, or about 40 rounds per second. Despite this being a significant reduction from the nearly 100 rounds per second fired by a standard Vulcan cannon, the installation proved too kinetic for the UH-1. Podded versions of the M24 20 mm cannon were tested in combat over Vietnam. There was a wide variety of 7.62 mm automatic weapons tested, including different installations of the M60 machine gun. AS-10 and SS-11 missiles were tested in several different configurations. High-capacity rocket launchers were also tested, such as the XM3 launcher, which had 24 launching tubes. Press photos were taken with the XM5 and XM3 installed on the same aircraft, but this arrangement could not be used because it was more than the gross take-off weight of the aircraft.[30]

During the Easter Offensive of 1972 by North Vietnam, experimental models of the TOW-firing XM26 were taken out of storage and sent to South Vietnam in response to the onslaught. The pilots had never fired a TOW missile before, and were given brief crash courses. Despite having little training with the units, the pilots managed to hit targets with 151 of the 162 missiles fired in combat, including a pair of tanks. The airborne TOW launchers were known as "Hawks Claws" and were based at Camp Holloway.[30] During the conflict, 7,013 UH-1s served in Vietnam and of these 3,305 were destroyed. In total, 1,151 pilots were killed, along with 1,231 other crew members (these figures are not including Army of the Republic of Vietnam losses).[31][4]

Post Vietnam, the US Army continued to operate large numbers of Iroquois; they would see further combat during the US invasion of Grenada in 1983, the US invasion of Panama in 1989, and the Gulf War in 1991.[4] In the latter conflict, in excess of 400 Iroquois performed a variety of missions in the region; over a nine-month period, the fleet cumulatively reached 31,000 flight hours and achieved a stable fully mission capable rate of 70%. The type comprised more than 20% of all rotorcraft across the coalition and recorded 21% of the overall flying hours.[4] Even after the Gulf War, the US Army had more than 2,800 Iroquois in its inventory; in particular, 389 UH-1Vs comprised 76% of the Army's medevac aircraft. Nevertheless, plans were mooted as early as 1992 to undertake a slow withdrawal of the aging type in favor of larger and more technologically advanced rotorcraft.[4]

The US Army phased out the UH-1 with the introduction of the Sikorsky UH-60 Black Hawk, although the Army UH-1 Residual Fleet had around 700 UH-1s that were to be retained until 2015, primarily in support of Army Aviation training at Fort Rucker and in selected Army National Guard units. Army support for the craft was intended to end in 2004; The UH-1 was retired from active Army service in early 2005.[32] During 2009, Army National Guard retirements of the UH-1 accelerated with the introduction of the Eurocopter UH-72 Lakota.[33][34][35] The final UH-1 was retired in 2016.[36][4]

U.S. Air Force

In October 1965, the United States Air Force (USAF) 20th Helicopter Squadron was formed at Tan Son Nhut Air Base in South Vietnam, equipped initially with CH-3C helicopters. By June 1967, the UH-1F and UH-1P were also added to the unit's inventory and, by the end of the year, the entire unit had shifted from Tan Son Nhut to Nakhon Phanom Royal Thai Air Force Base, with the CH-3s transferring to the 21st Helicopter Squadron. On 1 August 1968, the unit was redesignated the 20th Special Operations Squadron. The 20th SOS's UH-1s were known as the Green Hornets, stemming from their color, a primarily green two-tone camouflage (green and tan) was carried, and radio call-sign "Hornet". The main role of these helicopters were to insert and extract reconnaissance teams, provide cover for such operations, conduct psychological warfare, and other support roles for covert operations especially in Laos and Cambodia during the so-called Secret War.[37]

USAF UH-1s were often equipped with automatic grenade launchers in place of the door guns. The XM-94 grenade launcher had been tested on Army rotorcraft prior to its use by the USAF. The unit was capable of firing 400 grenades per minute, up to 1,500 yards effective range.[38]

Into the twenty-first century, the USAF operates the UH-1N for support of intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) sites, including transport of security personnel and distinguished visitors.[39][40] On 24 September 2018, the USAF announced that the Boeing/Leonardo MH-139 (an AW-139 variant) had won a competition to replace the UH-1Ns.[41]

U.S. Navy

The US Navy acquired a number of surplus UH-1B helicopters from the U.S. Army, these rotorcraft were modified into gunships, outfitted with special gun mounts and radar altimeters. They were known as Seawolves in service with Navy Helicopter Attack (Light) (HA(L)-3). UH-1C helicopters were also acquired during the 1970s.[42][43] The Seawolves worked as a team with Navy river patrol operations.[44]

Four years after the disestablishment of HA(L)-3, the Navy determined that it still had a need for gunships, establishing two new Naval Reserve Helicopter Attack (Light) Squadrons as part of the newly formed Commander, Helicopter Wing Reserve (COMHELWINGRES) in 1976. Helicopter Attack Squadron (Light) Five (HA(L)-5), nicknamed the "Blue Hawks", was established at Naval Air Station Point Mugu, California on 11 June 1977 and its sister squadron, Helicopter Attack Squadron (Light) Four (HA(L)-4), known as the Red Wolves, was formed at Naval Air Station Norfolk, Virginia on 1 July 1976.[45]

Drug Enforcement Administration

The UH-1H has been used on multiple occasions by the American Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA); initially, these were usually borrowed from the U.S. Army to support planned missions, such for Operation Snowcap, a large multi-year counter-narcotics action covering nine countries across Latin America.[46]

During the War in Afghanistan, the DEA made use of a number of UH-1s stationed in the country for the purpose of conducting counter-narcotics raids. Operated by contractors, these Hueys provide transportation, surveillance, and air support for DEA FAST teams. During July 2009, four UH-1Hs and two Mi-17s were used in a raid that led to the arrest of an Afghan Border Police commander on corruption charges.[47]

Argentina

Nine Argentine Army Aviation UH-1Hs and two Argentine Air Force Bell 212 were included with the aircraft deployed during the Falklands War. They performed general transport and SAR missions and were based at Port Stanley (BAM Puerto Argentino). Two of the Hueys were destroyed and, after the hostilities had ended, the remainder were captured by the British military.[48][49] Three captured aircraft survive as museum pieces in England and Falklands.

Australia

The Royal Australian Air Force employed the UH-1H until 1989. Iroquois helicopters of No. 9 Squadron RAAF were deployed to South Vietnam in mid 1966 in support of the 1st Australian Task Force. In this role they were armed with single M60 doorguns. In 1969 four of No. 9 Squadron's helicopters were converted to gunships (known as 'Bushrangers'), armed with two fixed forward firing M134 7.62 mm minigun (one each side) and a 7-round rocket pod on each side. Aircrew were armed with twin M60 flexible mounts in each door. UH-1 helicopters were used in many roles including troop transport, medevac and Bushranger gunships for armed support.[50] No. 35 Squadron and No. 5 Squadron also operated the Iroquois in various roles through the 1970s and 1980s. Between 1982 and 1986, the squadron contributed aircraft and aircrew to the Australian helicopter detachment which formed part of the Multinational Force and Observers peacekeeping force in the Sinai Peninsula, Egypt.[50] During 1988, the RAAF began to re-equip with S-70A Blackhawks.[50]

In 1989 and 1990, the RAAF's UH-1H Iroquois were subsequently transferred to the 171st Aviation Squadron in Darwin, Northern Territory and the 5th Aviation Regiment based in Townsville, Queensland following the decision that all battlefield helicopters would be operated by the Australian Army.[51] On 21 September 2007, the Australian Army retired the last of their Bell UH-1s. The last flight occurred in Brisbane on that day with the aircraft replaced by MRH-90 medium helicopters and Tiger armed reconnaissance helicopters.[52]

The Royal Australian Navy's 723 Squadron also operated seven UH-1B from 1964 to 1989, with three of these aircraft lost in accidents during that time.[53] 723 Squadron deployed Iroquois aircraft and personnel as part of the Experimental Military Unit during the Vietnam War.[54]

El Salvador

Numerous UH-1s were operated by the Salvadoran Air Force; during the 1980s, it became the biggest and most experienced combat helicopter force in Central and South America, fighting for over a decade during the Salvadoran Civil War and having been trained by US Army in tactics developed during the Vietnam War. By the start of 1985, El Salvador had 33 UH-1s in its inventory, some configured as gunships and others as transports; furthermore, in the following years, the country expanded its UH-1 fleet further with assistance from the US government.[55][56] Several Salvadorean UH-1M and UH-1H helicopters used were modified to carry bombs instead of rocket pods.[57] The UH-1s enabled the military to avoid ground routes vulnerable to guerilla ambushes; the gunships were typically used to suppress hostile forces ahead of troops being inserted by UH-1 transports.[55]

Germany

.jpg.webp)

The German aerospace company Dornier constructed 352 UH-1Ds under license between 1967 and 1981 for the West German Bundeswehr.[58] These saw service with both the German Army and German Air Force as utility helicopters, they were also commonly used for search and rescue (SAR) missions.[9] Having been replaced by newer twin-engined Eurocopter EC145s, the last UH-1Ds in German service were withdrawn on 12 April 2021.[58][59]

Israel

Israel withdrew its UH-1s from service in 2002, after 33 years of operation. They were replaced by Sikorsky UH-60 Blackhawk helicopters with an initial batch of 10 delivered during 1994. While some were passed on to pro-Israeli militias in Lebanon, eleven other UH-1Ds were reportedly sold to a Singapore-based logging company but were, instead, delivered in October 1978 to the Royal Rhodesian Air Force to skirt a United Nations-endorsed embargo imposed on the country during the Rhodesian Bush War.[60][61]

Japan

In 2005, a pair of Japan Ground Self-Defense Force (JGSDF) UH-1 helicopters were deployed to Pakistan for earthquake disaster relief.[62] During 2010, after floods in Pakistan, UH-1s were again deployed to the country to aid in disaster relief.[63][64] Japanese UH-1s have also been periodically used to conduct water bombing against fires.[65][66]

In the aftermath of the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami, Japan's UH-1 fleet was extensively deployed across the country for disaster relief purposes; they also conducted reconnaissance flights over the stricken Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant while carrying radiation detection equipment to help inform planners of the plant's condition.[67][68]

By the early 2020s, Japan's Acquisition, Technology & Logistics Agency was in the process of recapitalising much of the JGSDF's rotarywing capability; it is planned for a locally-built model of the twin-engined multirole Bell 412 helicopter to replace the remaining UH-1s in Japanese service.[69][70]

Lebanon

During the early 1990s, the Lebanese Air Force (LAF) inducted their first UH-1 helicopters.[71] During the 2007 Lebanon conflict, at the Battle of Nahr el-Bared in North Lebanon, the Lebanese Army, lacking fixed-wing aircraft, modified several UH-1Hs to carry 500 lb (227 kg) Mark 82 bombs, enabling it to perform helicopter bombing, and used it to strike militant-held positions. Specifically, special mounting points were installed along the sides of each Huey for the carriage of these high explosive bombs.[72] In the aftermath of the 2020 Beirut explosion, UH-1s participated in the disaster response, and were used to extinguish fires.[71]

Typically, the fleet is tasked with performing search and rescue, troop transport, aerial firefighting and utility missions.[71] In the late 2010s, specially modified UH-1Ds participated in the first LIDAR mapping exercise in the country.[73] During February 2021, an additional three Bell UH-1H-IIs were delivered to the LAF by Bell to augment their existing fleet.[71]

New Zealand

The Royal New Zealand Air Force had an active fleet of 13 Iroquois serving with No. 3 Squadron RNZAF.[74] The first delivery was five UH-1D in 1966 followed in 1970 by nine UH-1H and one more UH-1H in 1976. All of the UH-1D aircraft were upgraded to 1H specification during the 1970s. Two ex-U.S. Army UH-1H attrition airframes were purchased in 1996. Three aircraft have been lost in accidents.[75]

The RNZAF has retired the Iroquois, with the NHIndustries NH90 as its replacement.[76] Eight active NH90 helicopters plus one spare have been procured. This process was initially expected to be completed by the end of 2013, but was delayed until 2016. Individual aircraft were retired as they reach their next major group servicing intervals; the UH-1H was retired as the NH90 fleet stood up.[77] On 21 May 2015, the remaining UH-1H fleet of six helicopters conducted a final tour of the country ahead of its planned retirement on 1 July. During 49 years of service the type had seen service in areas including the U.K., Southeast Asia, Timor, the Solomon Islands, various South Pacific nations, and the Antarctic.[78]

Philippines

The Philippine Air Force (PAF) has a long history of acquiring United States Air Force assets, including the Bell UH-1. In PAF service, the type was regularly used to combat local insurgents as well as to conduct disaster relief operations after several earthquakes and typhoons hit the nation.[79] Francis Ford Coppola filmed Apocalypse Now in the Philippines primarily because President Ferdinand Marcos agreed to let Coppola use Philippine Hueys to film the iconic scene with Robert Duvall as Lt. Colonel Kilgore.[80]

During 2013, the PAF was pursuing the acquisition of 21 used UH-1H helicopters; the deal reportedly included their refurbishment prior to delivery.[81][82] Furthermore, during October 2019, the Philippines made a deal with Japan to acquire some of its spare parts inventory; this reportedly was to facilitate the restoration of seven stored UH-1s to flightworthy condition.[83] By January 2021, the PAF had 13 UH-1H and 10 UH-1D helicopters in an operational condition.[84]

On 23 January 2021, President Rodrigo Duterte announced a plan to retire all of the PAF's remaining UH-1 helicopters,[85] following a series of crashes involving the type. The latest crash occurred on 16 January 2021, killing seven passengers and prompting the grounding of all Hueys for further inspection.[86] On 14 October 2021, the PAF officially decommissioned the remainder of its UH-1D fleet, despite some having only been acquired seven years prior; the retired rotorcraft were stored at Clark Air Base.[79] The role of the UH-1 is to be performed by recently delivered UH-60 Black Hawk helicopters instead;[87] in January 2022, a deal to buy 32 new-build Black Hawks was announced.[88]

Rhodesia

Very late in the Rhodesian Bush War, the Rhodesian Air Force obtained 11 former Israeli Agusta-Bell 205As in violation of sanctions on the nation, allegedly having used a series of intermediaries to evade them.[89][90] Locally known as Cheetahs, these helicopters were returned to a flightworthy condition and then assigned to No. 8 Squadron, after which they participated in the counter-insurgency effort, usually functioning as armed gunships as well as troop transports. During September 1979, one Cheetah was lost in combat after being hit by an RPG while flying over Mozambique. At least another three other UH-1s were also lost. The surviving helicopters were put up for sale in 1990.[91][92]

Yemen

In July 2009, Yemen received four UH-1Hs. These remained grounded for almost all the time they were in Yemen; at least one helicopter was heavily damaged during Saudi-led airstrikes on Al Daylami and Al Anad Air Bases.[91]

Variant overview

U.S. military variants

- XH-40: The initial Bell 204 prototype. Three prototypes were built, equipped with the Lycoming XT-53-L-1 engine of 700 shp (520 kW).[14]

- YH-40: Six aircraft for evaluation, as XH-40 with 12-inch (300 mm) cabin stretch and other modifications.

- Bell Model 533: One YH-40-BF rebuilt as a flight test bed with turbojet engines and wings.

- HU-1A: Initial Bell 204 production model, redesignated as the UH-1A in 1962.[14] 182 built.[93]

- HU-1B: Upgraded HU-1A, various external and rotor improvements. Redesignated UH-1B in 1962.[14] 1014 built plus four prototypes designated YUH-1B.[93]

- NUH-1B: a single test aircraft, serial number 64–18261.[14]

- UH-1C: The UH-1B gunship lacked the power necessary to carry weapons and ammunition and keep up with transport Hueys. So Bell designed yet another variant, the UH-1C, intended strictly for the gunship role. It is an UH-1B with improved engine, modified blades and rotor-head for better performance in the gunship role.[14] 767 built.[93]

- YUH-1D: Seven pre-production prototypes of the UH-1D.

- UH-1D Iroquois: Initial Bell 205 production model (long fuselage version of the 204). Designed as a troop carrier to replace the CH-34 then in US Army service.[14] 2008 built; many later converted to UH-1H standard.[93]

- HH-1D: Army crash rescue variant of UH-1D.[14]

- UH-1E: UH-1B/C for USMC with different avionics and equipment.[14] 192 built.[93]

- NUH-1E: UH-1E configured for testing.

- TH-1E: UH-1C configured for Marine Corps training. Twenty were built in 1965.[14]

- UH-1F: UH-1B/C for USAF with General Electric T58-GE-3 engine of 1,325 shp (988 kW).[14] 120 built.[93]

- UH-1H: Improved UH-1D with a Lycoming T53-L-13 engine of 1,400 shp (1,000 kW).[14] 5435 built.[93]

- CUH-1H: Canadian Forces designation for the UH-1H utility transport helicopter. Redesignated CH-118.[14][94] A total of 10 built.[93]

- EH-1H: Twenty-two aircraft converted by installation of AN/ARQ-33 radio intercept and jamming equipment for Project Quick Fix.

- HH-1H: Search and rescue (SAR) variant for the USAF with rescue hoist.[14] A total of 30 built.[93]

- JUH-1: Five UH-1Hs converted to SOTAS battlefield surveillance configuration with belly-mounted airborne radar.[14]

- TH-1H: Recently modified UH-1Hs for use as basic helicopter flight trainers by the USAF.

- HH-1K: Purpose-built SAR variant of the Model 204 for the US Navy with USN avionics and equipment.[14] 27 built.[93]

- TH-1L: Helicopter flight trainer based on the HH-1K for the USN. A total of 45 were built.[14]

- UH-1L: Utility variant of the TH-1L. Eight were built.[14]

- UH-1M: Gunship specific UH-1C upgrade with Lycoming T53-L-13 engine of 1,400 shp (1,000 kW).[14]

- UH-1N: Initial Bell 212 production model, the Bell "Twin Pac" twin-engined Huey powered by Pratt & Whitney Canada T400-CP-400.[14]

- UH-1P: UH-1F variant for USAF for special operations use and attack operations used solely by the USAF 20th Special Operations Squadron, "the Green Hornets".[14]

- EH-1U: No more than two UH-1H aircraft modified for Multiple Target Electronic Warfare System (MULTEWS).[95]

- UH-1V: Aeromedical evacuation, rescue version for the US Army.[14]

- EH-1X: Ten Electronic warfare UH-1Hs converted under "Quick Fix IIA".[14]

- UH-1Y: Upgraded variant developed from existing upgraded late model UH-1Ns, with additional emphasis on commonality with the AH-1Z.

Note: In U.S. service, the G, J, Q, R, S, T, W and Z model designations are used by the AH-1. The UH-1 and AH-1 are considered members of the same H-1 series. The military does not use I (India) or O (Oscar) for aircraft designations to avoid confusion with "one" and "zero" respectively.

Other military variants

- Bell 204: Bell Helicopters company designation, covering aircraft from the XH-40, YH-40 prototypes to the UH-1A, UH-1B, UH-1C, UH-1E, UH-1F, HH-1K, UH-1L, UH-1P and UH-1M production aircraft.

- Agusta-Bell AB 204: Military utility transport helicopter. Built under license in Italy by Agusta.

- Agusta-Bell AB 204AS: Anti-submarine warfare, anti-shipping version of the AB 204 helicopter.

- Fuji-Bell HU-1B/HU-1H: Military utility transport helicopter for the Japan Ground Self-Defense Force. Built under license in Japan by Fuji Heavy Industries.[96]

- Bell 205: Bell Helicopters company designation of the UH-1D and UH-1H helicopters.

- Bell 205A-1: Military utility transport helicopter version, initial version based on the UH-1H.

- Bell 205A-1A: As 205A-1, but with armament hardpoints and military avionics. Produced specifically for Israeli contract.

- Agusta-Bell 205: Military utility transport helicopter. Built under license in Italy by Agusta.

- AIDC UH-1H: Military utility transport helicopter. Built under license in Taiwan by Aerospace Industrial Development Corporation.[97]

- Dornier UH-1D: Military utility transport helicopter. Built under license in Germany by Dornier Flugzeugwerke.[97]

- UH-1G: Unofficial name applied locally to at least one armed UH-1H by the Khmer Air Force in Cambodia.[98]

- Fuji-Bell UH-1J: An improved Japanese version of the UH-1H built under license in Japan by Fuji Heavy Industries was locally given the designation UH-1J.[99] Among improvements were an Allison T53-L-703 turboshaft engine providing 1,343 kW (1,800 shp), a vibration-reduction system, infrared countermeasures, and a night-vision-goggle (NVG) compatible cockpit.[100]

- Bell 211 Huey Tug With up-rated dynamic system and larger wide chord blades, the Bell 211 was offered for use as the US Army's prime artillery mover, but not taken up.[9]

- Bell Huey II: A modified and re-engined UH-1H, improvements were an Allison T53-L-703 turboshaft engine providing 1,343 kW (1,800 shp), a vibration-reduction system, infrared countermeasures and a night-vision-goggle (NVG) compatible cockpit. This significantly improves performance and cost-effectiveness. Currently offered by Bell to all current military users of the type.[101]

- UH-1/T700 Ultra Huey: Upgraded commercial version, fitted with a 1,400-kW (1900-shp) General Electric T700-GE-701C turboshaft engine.[102]

Operators

Aircraft on display

Accidents

- 23 July 1982: Twilight Zone accident: A Bell UH-1 Iroquois helicopter crashed at Indian Dunes in Valencia, California, during the making of Twilight Zone: The Movie. Actor Vic Morrow and two child actors were killed.

- 17 January 2018: A Sapphire Aviation UH-1H crashed near Raton, New Mexico, United States. Five of the six people on board were killed, including Zimbabwean politician Roy Bennett.

Specifications (UH-1H)

Data from Jane's All the World's Aircraft 1987-88[103]

General characteristics

- Crew: 1–4

- Capacity: 3,880 lb (1,760 kg) including 11-14 troops, 6 stretchers and attendant, or equivalent cargo

- Length: 57 ft 9+5⁄8 in (17.618 m) with rotors

- Width: 9 ft 6+1⁄2 in (2.908 m) (over skids)

- Height: 14 ft 5+1⁄2 in (4.407 m) (tail rotor turning)

- Empty weight: 5,210 lb (2,363 kg)

- Gross weight: 9,039 lb (4,100 kg) (mission weight)

- Max takeoff weight: 9,500 lb (4,309 kg)

- Powerplant: 1 × Lycoming T53-L-13 turboshaft, 1,400 shp (1,000 kW) (limited to 1,100 shp (820 kW) by transmission)

- Main rotor diameter: 48 ft 0 in (14.63 m)

- Main rotor area: 1,809.56 sq ft (168.114 m2)

Performance

- Maximum speed: 127 mph (204 km/h, 110 kn) (at maximum takeoff weight; also Vne at this weight)

- Cruise speed: 127 mph (204 km/h, 110 kn) (at 5,700 ft (1,700 m) at maximum takeoff weight)

- Range: 318 mi (511 km, 276 nmi) (with maximum fuel, no reserves, at sea level)

- Service ceiling: 12,600 ft (3,800 m) (at maximum takeoff weight)

- Rate of climb: 1,600 ft/min (8.1 m/s) at sea level (at maximum takeoff weight)

- Disk loading: 5.25 lb/sq ft (25.6 kg/m2)

- Power/mass: 0.1159 hp/lb (0.1905 kW/kg)

Armament

various including:

- 7.62 mm machine guns

- 2.75 in (70 mm) rocket pods

Notable appearances in media

The image of American troops disembarking from a Huey has become an iconic image of the Vietnam War, and can be seen in many films, video games and television shows on the subject, as well as more modern settings. The UH-1 is seen in many films about the Vietnam War, including The Green Berets, The Deer Hunter, Platoon, Hamburger Hill, Apocalypse Now,[80] Casualties of War, and Born on the Fourth of July. It is prominently featured in We Were Soldiers as the main helicopter used by the Air Cavalry in the Battle of Ia Drang. Author Robert Mason recounts his career as a UH-1 "Slick" pilot in his memoir, Chickenhawk.

The 2002 journey of Huey 091, displayed in the Smithsonian National Museum of American History, is outlined in the 2004 documentary In the Shadow of the Blade.[104]

See also

- Bell Huey family – overview of all models

Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

Related lists

References

Footnotes

- The total power rating of the T53-L-1A is 860 shp (640 kW). Military engines are often derated to improve reliability of the aircraft powertrain and to provide a temporary period of higher power output without exceeding the limits of the engine.

- The 7 January 1965-edition of Flight International magazine states that the L-11 engine is similar to the L-9 in power, but with a multi-fuel capability.

- Earlier UH-1s had some magnesium components.

- Quote: "The UH-1B was the first helicopter gunship to achieve widespread combat use. It was also the first to carry the name "Cobra"

Citations

- "Bell UH-1V 'Huey'". Delaware Valley Historical Aircraft Association. March 2008. Archived from the original on 11 May 2008. Retrieved 25 February 2009.

- "Bell UH-1Y pocket guide" (PDF). Bell Helicopter. March 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 December 2010. Retrieved 20 January 2010.

- Weinert 1991, p. 203.

- Fardink, Paul J. (September–October 2016). "Huey Turns 60: A Retrospective Review of the UH-1's Remarkable Military Service" (PDF). vtol.org.

- Chapman, S. "Up from Kitty Hawk: 1954–63" (PDF). Air Force Magazine, Air Force Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 May 2011. Retrieved 5 October 2008.

- "Aeroengines 1957". Flight. 26 July 1957. Archived from the original on 19 November 2009. Retrieved 10 August 2009.

- Donald, David, ed. "Bell 204"; "Bell 205". The Complete Encyclopedia of World Aircraft. New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 1997. ISBN 0-7607-0592-5.

- Johnson, E. R.; Williams, Ted (29 November 2021). American Military Helicopters and Vertical/Short Landing and Takeoff Aircraft Since 1941. McFarland. p. 123. ISBN 978-1-4766-4342-7. Retrieved 23 August 2023.

- Drendel 1983, pp. 9–21.

- Apostolo 1984, pp. 47–48.

- McGowen 2005, p. 100.

- Pattillo 2001, p. 208.

- Dobson, G (7 January 1965). "Helicopter powerplants: The world scene". Flight.

- Mutza 1986, .

- "UH-1B Huey". cactusairforce.com. Retrieved 20 January 2023.

- Donald 1997. p. 113.

- Donald, David. Modern Battlefield Warplanes. London: AIRTime Publishing, 2004. ISBN 1-880588-76-5.

- Reim, Garrett (12 December 2018). "RETROSPECTIVE: How the UH-1 'Huey' changed modern warfare". Flight International.

- Trimble, Stephen (18 August 2008). "UH-1Y declared operational after 12-year development phase". Flightglobal.com. Archived from the original on 2 September 2008. Retrieved 24 January 2010.

- Endres, Gunter, ed. (2006). Jane's Helicopter Markets and Systems. London: Jane's Information Group. ISBN 978-0-7106-2684-4.

- DAOT 5: C-12-118-000/MB-000 Operating Instructions CH118 Helicopter (unclassified), Change 2, 23 April 1987. Department of National Defence

- Bowen, C. W.; Braddock, C. E.; Walker, R. D. (May 1969). USAAVLABS Technical Report 68-57 Installation of a high-reduction-ratio transmission in the UH-1 helicopter (PDF) (Report). United States Army Aviation Material Laboratories. pp. Figure 1 and p. 7.

- Leishman, Gordon J. (24 April 2006). Principles of Helicopter Aerodynamics with CD Extra. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85860-1. Retrieved 7 July 2022.

- Price, Major David H. "The Army Aviation Story Part XI: The Mid-1960s" (PDF). rucker.army.mil. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- Bishop, Chris (2006). Huey Cobra Gunships. London: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84176-984-3.

- Drendel 1974, p. 9.

- Mason, Robert (1984). Chickenhawk. New York: Viking Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-303571-1.

- "U.S. Army Helicopter Weapon Systems: Operations with XM26 TOW missile system in Kontum (1972)". army.mil. Archived from the original on 5 June 2008. Retrieved 25 August 2010.

- "Col. James P. Fleming". United States Air Force. 29 May 2012. Archived from the original on 21 October 2012. Retrieved 29 May 2012.

- Mutza 2013, p. 39.

- "Helicopter Losses During the Vietnam War" (PDF). Vietnam Helicopter Pilots Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 October 2008. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- "Death Traps No More". Strategypage.com. 11 April 2013. Archived from the original on 15 May 2013. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- Mehl, Maj. Thomas W. "A Final LZ". Army National Guard. Archived from the original on 12 July 2009. Retrieved 25 August 2010.

- Sommers, Larry (4 May 2009). "Huey Retirement". Army National Guard. Archived from the original on 8 January 2010. Retrieved 25 August 2010.

- Soucy, Staff Sgt. Jon (3 December 2009). "New Helicopters Delivered to District of Columbia National Guard". Army National Guard. Archived from the original on 10 March 2011. Retrieved 25 August 2010.

- Edwards, J. D. "Last UH-1 Huey, a 42-year military veteran retires". wsmr.army.mil. Archived from the original on 23 July 2017. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- Mutza 1987, pp. 22–31.

- Mutza 2012, p. 33.

- "UH-1N Huey". U.S. Air Force. 30 September 2015. Archived from the original on 22 August 2017. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- "US Air Force targets July for UH-1N replacement solicitation". IHS Jane's Defence Weekly. 8 June 2017. Archived from the original on 22 August 2017. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- Insinna, Valerie (24 September 2018). "The Air Force picks a winner for its Huey replacement helicopter contract". defensenews.com. Retrieved 25 September 2018.

- "Navy Seawolves". seawolf.org. Archived from the original on 21 September 2010. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- "History of US Navy Combat Search and Rescue". Archived from the original on 8 July 2011. Retrieved 12 November 2010.

- "River Patrol Force". Navy News Release. 1969. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- "BLUEHAWKS of HAL-5". bluehawksofhal-5.org. Archived from the original on 8 January 2015. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- "History" (PDF). Drug Enforcement Administration. p. 63. Retrieved 27 June 2022.

- "Afghan hash bust underscores official corruption". Wired.com. Archived from the original on 24 May 2013. Retrieved 4 October 2009.

- "Bell 212". fuerzaaerea.mil.ar. 25 August 2010. Archived from the original on 17 April 2009. Retrieved 25 May 2009.

- "ElBell 212 en la Fuerza Aérea". FAA official magazine. Archived from the original on 28 October 2008. Retrieved 27 June 2022.

- Eather 1995, p. 40.

- Eather 1995, pp. 150–151.

- Stackpool, Andrew (22 July 2010). "40 Years of Top Service". Army. Canberra, Australia: Directorate of Defence Newspapers. p. 10. Archived from the original on 17 December 2014. Retrieved 28 February 2013.

- "RAAF/Army A2/N9 Bell UH-1B/D/H Iroqois." Archived 11 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine ADF Serials. Retrieved: 31 July 2012.

- Australian Naval Aviation Museum (ANAM) 1998, p. 179.

- Frazier, Joseph B. (29 January 1985). "El Salvador To Get Four Helicopter Gunships, Four For Transport". apnews.com.

- "Guerillas regroup as Carter switches on Salvador arms". The New York Times. 25 January 1981.

- Cooper, Tom (1 September 2003). "El Salvador, 1980–1992". Air Combat Information Group. Archived from the original on 5 November 2008. Retrieved 3 September 2007.

- "Das Heer verabschiedet eine Legende (The Army says goodbye to a legend)". bundeswehr.de (in German). Retrieved 27 April 2021.

- Jennings, Gareth (6 July 2020). "H145 officially takes on domestic SAR role for German Army". janes.com.

- "Israel: UH-1". aeroflight.co.uk. Archived from the original on 3 March 2010. Retrieved 4 October 2009.

- Brent 1988, p. 14.

- "ASDF C-130s depart on Pakistan relief duty". Japan Times. 14 October 2005. Archived from the original on 2 April 2016. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- "GSDF choppers Pakistan-bound". Japan Times. 19 August 2010. Archived from the original on 2 April 2016. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- "Chopper unit back from Pakistan". Japan Times. 27 October 2010. Archived from the original on 2 April 2016. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- "GSDF helicopter makes emergency landing at Tottori airport". Japan Times. 29 March 2018. Archived from the original on 30 March 2018.

- "GSDF helicopter makes emergency landing at western Japan airport". Mainichi Shimbun. 29 March 2018. Archived from the original on 29 March 2018.

- Hiscock, Kyle W (March 2012). "Thesis: Japan's Self Defense Forces after the Great East Japan Earthquake: Toward a new Status Quo" (PDF). dtic.mil. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 February 2016. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

- Wasiolek, Piotr T. "Introduction to Aerial Radiological Measurements". osti.gov. Retrieved 27 June 2022.

- Waldron, Greg (24 June 2020). "JGSDF beefs up rotorcraft to address tougher neighbourhood". Flight International.

- Giovanzanti, Alessandra (19 July 2021). "Tokyo provides more details about JGDSF's new UH-2 helicopter". janes.com.

- "Bell delivers three Huey IIs to the Lebanese Air Force". verticalmag.com. 23 February 2021.

- Kahwaji, Riad (3 September 2007). "The victory – Lebanon developed helicopter bombers". Ya Libnan. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 3 September 2007.

- Rom, Jakob; Haas, Florian; Manuel, Stark; Dremel, Fabian; Becht, Michael; Kopetzky, Karin; Schwall, Christoph; Wimmer, Michael; Pfeifer, Norbert; Mardini, Mahmoud; Hermann, Genz (October 2020). "Between Land and Sea: An Airborne LiDAR Field Survey to Detect Ancient Sites in the Chekka Region/Lebanon Using Spatial Analyses". Open Archaeology. 6: 248–268. doi:10.1515/opar-2020-0113. S2CID 224769155.

- "RNZAF – 3 Squadron History". Royal New Zealand Air Force. Archived from the original on 6 February 2013. Retrieved 4 September 2012.

- "RNZAF – Aircraft – UH-1H Iroquois". Royal New Zealand Air Force. Archived from the original on 6 February 2013. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- "Air Force retires Iroquois". The New Zealand Herald. 22 September 2009. Retrieved 9 December 2021.

- "NH90". Royal New Zealand Air Force. Archived from the original on 11 February 2012. Retrieved 30 January 2012.

- Clark, Peter (22 May 2015). "RNZAF Huey embarks on final domestic tour". Flightglobal. Archived from the original on 10 June 2015. Retrieved 9 December 2021.

- "Philippine military decommissions 10 U.S.-made vintage helicopters". xinhuanet.com. 14 October 2021.

- De Semlyen, Phil (20 May 2011). "Anatomy of a Scene: Apocalypse Now". Empire Magazine. Archived from the original on 29 October 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- "PAF welcomes supply deal boosting helicopter fleet". The Philippine Star. 30 December 2013. Archived from the original on 3 July 2017.

- "DND set to acquire 21 refurbished Huey helicopters" (PDF). DND.gov.ph. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 July 2017. Retrieved 26 August 2013.

- Yeo, Mike (11 October 2019). "Philippine air force reactivates seven old Huey helos thanks to spares from Japan". defensenews.com.

- "Estimated Quantity of UH-1 Family of Helicopters of the Philippine Air Force". Maxdefense Philippines FB Page. Max Montero. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- "PRRD to retire all Huey helicopters in PAF fleet". Manila Bulletin. 24 January 2021. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- "Air Force grounds all Huey helicopters following Bukidnon crash". ABS-CBN News. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- "Philippines receives final batch of S-70i Black Hawk helos". asianmilitaryreview.com. 12 November 2021.

- "Philippines to buy 32 new Black Hawk helicopters". Bangkok Post. bangkokpost.com. 16 January 2022.

- "Rhodesia Admits U.S. Helicopters Used in War Against Guerrillas". The Washington Post. 15 December 1978. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 29 December 2015.

- Karadia, Chhotu (31 January 1979). "Mystery surrounding US-made Huey helicopters smuggled into Ian Smith's Rhodesia solved".

- "Zimbabwe – Air Force – Aircraft Types". Aeroflight. Archived from the original on 1 March 2010. Retrieved 20 May 2009.

- Tharp, Dan (16 June 2012). "Fire Force: Rhodesia's COIN Killing Machine (Part 3)". sofrep.com.

- Andrade 1987, p. 125.

- "Bell CH-118 Iroquois". Department of National Defence. Archived from the original on 10 May 2006. Retrieved 30 August 2007.

- Buley, Dennis (29 December 1999). "US Army's Fleet of Special Electronic Mission Aircraft". Aeroflight. Archived from the original on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 28 October 2008.

- "History: Subaru Bell 412EPX". Subaru Aerospace Company. Retrieved 27 June 2022.

- Goebel, Greg. "The Bell UH-1 Huey". vectorsite.net. Archived from the original on 5 April 2011. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- Forsgren, Jan (22 April 2007). "Aviation Royale Khmere/Khmer Air Force Aircraft". Aeroflight. Archived from the original on 22 October 2008. Retrieved 28 October 2008.

- (in Japanese) "UH-1J 多用途ヘリコプター". Archived from the original on 27 January 2008. Retrieved 11 December 2007.

- Goebel, Greg (1 December 2007). "The Bell UH-1 Huey: Foreign-Build Hueys". airvectors.net. Archived from the original on 1 October 2013. Retrieved 16 August 2009.

- Bell Textron Inc. (2021). "Huey II". bellflight.com. Archived from the original on 19 November 2021. Retrieved 9 December 2021.

- "The UH-1/T700 Ultra Huey helicopter powered by General Electric engines demonstrated high altitude/hot day capabilities during a series of flight demonstrations". Defense Daily. October 1994. Archived from the original on 12 January 2009. Retrieved 29 October 2008.

- Taylor, John W. R., ed. (1987). Jane's All the World's Aircraft 1987-88. London: Jane's Publishing Company Limited. p. 365. ISBN 0 7106-0850-0. Retrieved 8 September 2021.

- "In The Shadow of The Blade". intheshadowoftheblade.com. 2004. Archived from the original on 24 May 2019. Retrieved 5 August 2009.

Bibliography

- Andrade, John M. (1979). U.S. Military Aircraft Designations and Serials since 1909. Hersham, Surrey, UK: Midland Counties Publications. ISBN 0-904597-22-9.

- Apostolo, Giorgio (1984). Bell 204, Bell 205: The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Helicopters. New York: Bonanza Books. ISBN 0-517-43935-2.

- Australian Naval Aviation Museum, (ANAM) (1998). Flying Stations: A Story of Australian Naval Aviation. St Leonards, NSW: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-86448-846-8.

- Brent, W. A. (1988). Rhodesian Air Force A Brief History 1947–1980. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Freeworld Publications. ISBN 0-620-11805-9.

- Chant, Christopher (1996). Fighting Helicopters of the 20th Century: 20th Century Military Series. Christchurch, Dorset, UK: Graham Beehag Books. ISBN 1-85501-808-X.

- Debay, Yves (1996). Combat Helicopters. Paris: Histoire & Collections. ISBN 2-908182-52-1.

- Donald, David, ed. (1997). Bell Model 212 Twin Two-Twelve: The Complete Encyclopedia of World Aircraft. New York: Barnes & Noble Books. ISBN 0-7607-0592-5.

- Drendel, Lou (1974). Gunslingers in Action. Carrollton, Texas: Squadron/Signal Publications. ISBN 0-89747-013-3.

- Drendel, Lou (1983). Huey. Carrollton, Texas: Squadron/Signal Publications. ISBN 0-89747-145-8..

- Eather, Steve (1995). Flying Squadrons of the Australian Defence Force. Weston Creek, ACT: Aerospace Publications. ISBN 1-875671-15-3.

- Eden, Paul, ed. (2004). Bell UH-1 Iroquois: Encyclopedia of Modern Military Aircraft. London: Amber Books. ISBN 1-904687-84-9.

- Elliot, Bryn (March–April 1997). "Bears in the Air: The US Air Police Perspective". Air Enthusiast. No. 68. pp. 46–51. ISSN 0143-5450.

- Francillon, René, J. (1987). Vietnam: The War in the Air. New York: Arch Cape Press. ISBN 0-517-62976-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Guilmartin, John Francis; O'Leary, Michael (1988). The Illustrated History of the Vietnam War, Volume 11: Helicopters. New York: Bantam Books. ISBN 0-553-34506-0.

- McGowen, Stanley S. (2005). Helicopters: An Illustrated History of Their Impact. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-468-4.

- Mesko, Jim (1984). Airmobile: The Helicopter War in Vietnam. Carrollton, Texas: Squadron/Signal Publications. ISBN 0-89747-159-8.

- Mikesh, Robert C. (1988). Flying Dragons: The South Vietnamese Air Force. London: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 0-85045-819-6.

- Mutza, Wayne (2012). Helicopter Gunships: Deadly Combat Weapon Systems. Specialty Press. ISBN 978-1-58007-154-3.

- Mutza, Wayne (1986). UH-1 Huey in Action. Carrollton, Texas: Squadron/Signal Publications. ISBN 0-89747-179-2.

- Mutza, Wayne (December 1986 – April 1987). "Covertly to Cambodia". Air Enthusiast. No. 32. Bromley, UK: Pilot Press. pp. 22–31. ISSN 0143-5450.

- Mutza, Wayne (1992). UH-1 Huey in Color. Carrollton, Texas: Squadron/Signal Publications. ISBN 0-89747-279-9.

- Pattillo, Donald M. (2001). Pushing the Envelope: The American Aircraft Industry. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-08671-9.

- Specifications for Bell 204, 205 and 214 Huey Plus