Bent's rule

In chemistry, Bent's rule describes and explains the relationship between the orbital hybridization of central atoms in molecules and the electronegativities of substituents.[1][2] The rule was stated by Henry A. Bent as follows:[2]

Atomic s character concentrates in orbitals directed toward electropositive substituents.

The chemical structure of a molecule is intimately related to its properties and reactivity. Valence bond theory proposes that molecular structures are due to covalent bonds between the atoms and that each bond consists of two overlapping and typically hybridised atomic orbitals. Traditionally, p-block elements in molecules are assumed to hybridise strictly as spn, where n is either 1, 2, or 3. In addition, the hybrid orbitals are all assumed to be equivalent (i.e. the n + 1 spn orbitals have the same p character). Predictions using this approach are usually good, but they can be improved by allowing isovalent hybridization, in which the hybridised orbitals may have noninteger and unequal p character. Bent's rule provides a qualitative estimate as to how these hybridised orbitals should be constructed.[3] Bent's rule is that in a molecule, a central atom bonded to multiple groups will hybridise so that orbitals with more s character are directed towards electropositive groups, while orbitals with more p character will be directed towards groups that are more electronegative. By removing the assumption that all hybrid orbitals are equivalent spn orbitals, better predictions and explanations of properties such as molecular geometry and bond strength can be obtained.[4] Bent's rule has been proposed as an alternative to VSEPR theory as an elementary explanation for observed molecular geometries of simple molecules with the advantages of being more easily reconcilable with modern theories of bonding and having stronger experimental support.

The validity of Bent's rule for 75 bond types between the main group elements was examined recently.[5] For bonds with the larger atoms from the lower periods, trends in orbital hybridization depend strongly on both electronegativity and orbital size.

History

In the early 1930s, shortly after much of the initial development of quantum mechanics, those theories began to be applied towards molecular structure by Pauling,[6] Slater,[7] Coulson,[8] and others. In particular, Pauling introduced the concept of hybridisation, where atomic s and p orbitals are combined to give hybrid sp, sp2, and sp3 orbitals. Hybrid orbitals proved powerful in explaining the molecular geometries of simple molecules like methane, which is tetrahedral with an sp3 carbon atom and bond angles of 109.5° between the four equivalent C-H bonds. However, slight deviations from these ideal geometries became apparent in the 1940s.[9] A particularly well known example is water, where the angle between the two O-H bonds is only 104.5°. To explain such discrepancies, it was proposed that hybridisation can result in orbitals with unequal s and p character. A. D. Walsh described in 1947[9] a relationship between the electronegativity of groups bonded to carbon and the hybridisation of said carbon atom. Finally, in 1961, Bent published a major review of the literature that related molecular structure, central atom hybridisation, and substituent electronegativities [2] and it is for this work that Bent's rule takes its name.

Justification

Polar covalent bonds

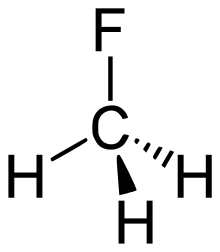

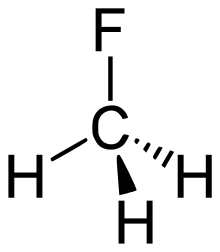

An informal justification of Bent's rule relies on s orbitals being lower in energy than p orbitals.[2] Bonds between elements of different electronegativities will be polar and the electron density in such bonds will be shifted towards the more electronegative element. Applying this to the molecule fluoromethane provides a demonstration of Bent's rule. Because carbon is more electronegative than hydrogen, the electron density in a C-H bond will be closer to the carbon atom. The energy of those electrons will depend heavily on the hybrid orbitals that carbon contributes to these bonds because of the increased electron density near the carbon. By increasing the amount of s character in those hybrid orbitals, the energy of those electrons can be reduced because s orbitals are lower in energy than p orbitals.

By the same logic and the fact that fluorine is more electronegative than carbon, the electron density in the C-F bond will be closer to fluorine. The hybrid orbital that carbon contributes to the C-F bond will have relatively less electron density in it than in the C-H case and so the energy of that bond will be less dependent on the carbon's hybridisation. By directing hybrid orbitals of more p character towards the fluorine, the energy of that bond is not increased very much.

Instead of directing equivalent sp3 orbitals towards all four substituents, shifting s character towards the C-H bonds will stabilize those bonds greatly because of the increased electron density near the carbon, while shifting s character away from the C-F bond will increase its energy by a lesser amount because that bond's electron density is further from the carbon. The atomic s character on the carbon atom has been directed toward the more electropositive hydrogen substituents and away from the electronegative fluorine, which is what Bent's rule predicts.

Although fluoromethane is a special case, the above argument can be applied to any structure with a central atom and 2 or more substituents. The key is that concentrating atomic s character in orbitals directed towards electropositive substituents by depleting it in orbitals directed towards electronegative substituents results in an overall lowering of the energy of the system. This stabilizing trade off is responsible for Bent's rule.

Nonbonding orbitals

Bent's rule can be extended to rationalize the hybridization of nonbonding orbitals as well. On the one hand, a lone pair (an occupied nonbonding orbital) can be thought of as the limiting case of an electropositive substituent, with electron density completely polarized towards the central atom. Bent's rule predicts that, in order to stabilize the unshared, closely held nonbonding electrons, lone pair orbitals should take on high s character. On the other hand, an unoccupied (empty) nonbonding orbital can be thought of as the limiting case of an electronegative substituent, with electron density completely polarized towards the ligand and away from the central atom. Bent's rule predicts that, in order to leave as much s character as possible for the remaining occupied orbitals, unoccupied nonbonding orbitals should maximize p character.

Experimentally, the first conclusion is in line with the reduced bond angles of molecules with lone pairs like water or ammonia compared to methane, while the second conclusion accords with the planar structure of molecules with unoccupied nonbonding orbitals, like monomeric borane and carbenium ions.

Consequences

Bent's rule can be used to explain trends in both molecular structure and reactivity. After determining how the hybridisation of the central atom should affect a particular property, the electronegativity of substituents can be examined to see if Bent's rule holds.

Bond angles

Knowing the angles between bonds is a crucial component in determining a molecular structure. In valence bond theory, covalent bonds are assumed to consist of two electrons lying in overlapping, usually hybridised, atomic orbitals from bonding atoms. Orbital hybridisation explains why methane is tetrahedral and ethylene is planar for instance. However there are deviations from the ideal geometries of spn hybridisation, as in water and ammonia whose bond angles are 104.5° and 107° respectively, which are less than the expected tetrahedral angle of 109.5°. The traditional approach to explain those differences is VSEPR theory. In that framework, valence electrons are assumed to lie in localized regions and lone pairs are assumed to repel each other to a greater extent than bonding pairs.

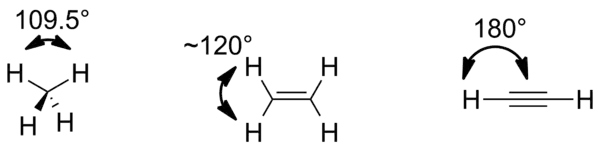

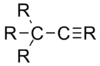

Bent's rule provides an alternative explanation as to why some bond angles differ from the ideal geometry. First, a trend between central atom hybridisation and bond angle can be determined by using the model compounds methane, ethylene, and acetylene. In order, the carbon atoms are directing sp3, sp2, and sp orbitals towards the hydrogens. The bond angles between substituents are ~109.5°, ~120°, and 180°; hybridised atomic orbitals with higher p character have a smaller angle between them. This result can be made rigorous and quantitative as Coulson's theorem (see Formal theory section below).

Now that the connection between hybridisation and bond angles has been made, Bent's rule can be applied to specific examples. The following were used in Bent's original paper, which considers the group electronegativity of the methyl group to be less than that of the hydrogen atom because methyl substitution reduces the acid dissociation constants of formic acid and of acetic acid.[2]

| Molecule | Bond angle between substituents |

|---|---|

Dimethyl ether | 111° |

Methanol | 107-109° |

Water | 104.5° |

Oxygen difluoride | 103.8° |

As one moves down the table, the substituents become more electronegative and the bond angle between them decreases. According to Bent's rule, as the substituent electronegativies increase, orbitals of greater p character will be directed towards those groups. By the above discussion, this will decrease the bond angle. This agrees with the experimental results. Comparing this explanation with VSEPR theory, VSEPR cannot explain why the angle in dimethyl ether is greater than 109.5°.

In predicting the bond angle of water, Bent's rule suggests that hybrid orbitals with more s character should be directed towards the lone pairs, while that leaves orbitals with more p character directed towards the hydrogens, resulting in deviation from idealized O(sp3) hybrid orbitals with 25% s character and 75% p character. In the case of water, with its 104.5° HOH angle, the OH bonding orbitals are constructed from O(~sp4.0) orbitals (~20% s, ~80% p), while the lone pairs consist of O(~sp2.3) orbitals (~30% s, ~70% p). As discussed in the justification above, the lone pairs behave as very electropositive substituents and have excess s character. As a result, the bonding electrons have increased p character. This increased p character in those orbitals decreases the bond angle between them to less than the tetrahedral 109.5°. The same logic can be applied to ammonia (107.0° HNH bond angle, with three N(~sp3.4 or 23% s) bonding orbitals and one N(~sp2.1 or 32% s) lone pair), the other canonical example of this phenomenon.

The same trend holds for nitrogen containing compounds. Against the expectations of VSEPR theory but consistent with Bent's rule, the bond angles of ammonia (NH3) and nitrogen trifluoride (NF3) are 107° and 102°, respectively.

Unlike VSEPR theory, whose theoretical foundations now appear shaky, Bent's rule is still considered to be an important principle in modern treatments of bonding.[10] For instance, a modification of this analysis is still viable, even if the lone pairs of H2O are considered to be inequivalent by virtue of their symmetry (i.e., only s, and in-plane px and py oxygen AOs are hybridized to form the two O-H bonding orbitals σO-H and lone pair nO(σ), while pz becomes an inequivalent pure p-character lone pair nO(π)), as in the case of lone pairs emerging from natural bond orbital methods.

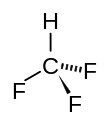

For a tetrahedral molecule such as difluoromethane with two types of atom bonded to the central atom, the C-F bond to the more electronegative substituent (F) will involve a carbon orbital with less s character than the C-H bond, so that the angle between the C-F bonds is less than the tetrahedral bond angle of 109.5°.[11]

Trigonal bipyramid molecules have both with axial and equatorial positions. If there are two types of substituents, the more electronegative substituent will prefer the axial position as there are smaller bond angles between axial and electronegative substituents than between two equatorial substituents.[11]

Bond lengths

Similarly to bond angles, the hybridisation of an atom can be related to the lengths of the bonds it forms.[2] As bonding orbitals increase in s character, the σ bond length decreases.

| Molecule | Average carbon–carbon bond length |

|---|---|

| 1.54 Å |

| 1.50 Å |

| 1.46 Å |

By adding electronegative substituents and changing the hybridisation of the central atoms, bond lengths can be manipulated. If a molecule contains a structure X-A--Y, replacement of the substituent X by a more electronegative atom changes the hybridization of central atom A and shortens the adjacent A--Y bond.

| Molecule | Average carbon–fluorine bond length |

|---|---|

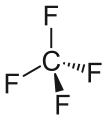

Fluoromethane | 1.388 Å |

Difluoromethane | 1.358 Å |

Trifluoromethane | 1.329 Å |

Tetrafluoromethane | 1.323 Å |

Because fluorine is so much more electronegative than hydrogen, in fluoromethane the carbon will direct hybrid orbitals higher in s character towards the three hydrogens than towards the fluorine. In difluoromethane, there are only two hydrogens so less s character in total is directed towards them and more is directed towards the two fluorines, which shortens the C—F bond lengths relative to fluoromethane. This trend holds all the way to tetrafluoromethane whose C-F bonds have the highest s character (25%) and the shortest bond lengths in the series.

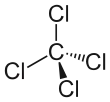

The same trend also holds for the chlorinated analogs of methane, although the effect is less dramatic because chlorine is less electronegative than fluorine.[2]

| Molecule | Average carbon–chlorine bond length |

|---|---|

Chloromethane | 1.783 Å |

Dichloromethane | 1.772 Å |

Trichloromethane | 1.767 Å |

Tetrachloromethane | 1.766 Å |

The above cases seem to demonstrate that the size of the chlorine is less important than its electronegativity. A prediction based on sterics alone would lead to the opposite trend, as the large chlorine substituents would be more favorable far apart. As the steric explanation contradicts the experimental result, Bent's rule is likely playing a primary role in structure determination.

JCH Coupling constants

Perhaps the most direct measurement of s character in a bonding orbital between hydrogen and carbon is via the 1H−13C coupling constants determined from NMR spectra. Theory predicts that JCH values will be much higher in bonds with more s character.[12][13] In particular, the one bond 13C-1H coupling constant 1J13C-1H is related to the fractional s character of the carbon hybrid orbital used to form the bond through the empirical relationship , where is the s character. (For instance the pure sp3 hybrid atomic orbital found in the C-H bond of methane would have 25% s character resulting in an expected coupling constant of 500 Hz × 0.25 = 125 Hz, in excellent agreement with the experimentally determined value.)

| Molecule | JCH (of the methyl protons) |

|---|---|

Methane | 125 Hz |

Acetaldehyde | 127 Hz |

1,1,1–Trichloroethane | 134 Hz |

Methanol | 141 Hz |

Fluoromethane | 149 Hz |

As the electronegativity of the substituent increases, the amount of p character directed towards the substituent increases as well. This leaves more s character in the bonds to the methyl protons, which leads to increased JCH coupling constants.

Inductive effect

The inductive effect can be explained with Bent's rule.[14] The inductive effect is the transmission of charge through covalent bonds and Bent's rule provides a mechanism for such results via differences in hybridisation. In the table below,[15] as the groups bonded to the central carbon become more electronegative, the central carbon becomes more electron-withdrawing as measured by the polar substituent constant. The polar substituent constants are similar in principle to σ values from the Hammett equation, as an increasing value corresponds to a greater electron-withdrawing ability. Bent's rule suggests that as the electronegativity of the groups increase, more p character is diverted towards those groups, which leaves more s character in the bond between the central carbon and the R group. As s orbitals have greater electron density closer to the nucleus than p orbitals, the electron density in the C−R bond will more shift towards the carbon as the s character increases. This will make the central carbon more electron-withdrawing to the R group.[9] Thus, the electron-withdrawing ability of the substituents has been transferred to the adjacent carbon, as the inductive effect predicts.

| Substituent | Polar substituent constant (larger values imply greater electron-withdrawing ability) |

|---|---|

t–Butyl | −0.30 |

Methyl | 0.00 |

Chloromethyl | 1.05 |

Dichloromethyl | 1.94 |

Trichloromethyl | 2.65 |

Formal theory

Bent's rule provides an additional level of accuracy to valence bond theory. Valence bond theory proposes that covalent bonds consist of two electrons lying in overlapping, usually hybridised, atomic orbitals from two bonding atoms. The assumption that a covalent bond is a linear combination of atomic orbitals of just the two bonding atoms is an approximation (see molecular orbital theory), but valence bond theory is accurate enough that it has had and continues to have a major impact on how bonding is understood.[1]

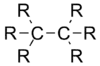

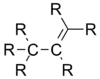

In valence bond theory, two atoms each contribute an atomic orbital and the electrons in the orbital overlap form a covalent bond. Atoms do not usually contribute a pure hydrogen-like orbital to bonds.[6] If atoms could only contribute hydrogen-like orbitals, then the experimentally confirmed tetrahedral structure of methane would not be possible as the 2s and 2p orbitals of carbon do not have that geometry. That and other contradictions led to the proposing of orbital hybridisation. In that framework, atomic orbitals are allowed to mix to produce an equivalent number of orbitals of differing shapes and energies. In the aforementioned case of methane, the 2s and three 2p orbitals of carbon are hybridized to yield four equivalent sp3 orbitals, which resolves the structure discrepancy. Orbital hybridisation allowed valence bond theory to successfully explain the geometry and properties of a vast number of molecules.

In traditional hybridisation theory, the hybrid orbitals are all equivalent.[16] Namely the atomic s and p orbital(s) are combined to give four spi3 = 1⁄√4(s + √3pi) orbitals, three spi2 = 1⁄√3(s + √2pi) orbitals, or two spi = 1⁄√2(s + pi) orbitals. These combinations are chosen to satisfy two conditions. First, the total amount of s and p orbital contributions must be equivalent before and after hybridisation. Second, the hybrid orbitals must be orthogonal to each other.[16] If two hybrid orbitals were not orthogonal, by definition they would have nonzero orbital overlap. Electrons in those orbitals would interact and if one of those orbitals were involved in a covalent bond, the other orbital would also have a nonzero interaction with that bond, violating the two electron per bond tenet of valence bond theory.

To construct hybrid s and p orbitals, let the first hybrid orbital be given by s + √λipi, where pi is directed towards a bonding group and λi determines the amount of p character this hybrid orbital has. This is a weighted sum of the wavefunctions. Now choose a second hybrid orbital s + √λjpj, where pj is directed in some way and λj is the amount of p character in this second orbital. The value of λj and direction of pj must be determined so that the resulting orbital can be normalized and so that it is orthogonal to the first hybrid orbital. The hybrid can certainly be normalized, as it is the sum of two normalized wavefunctions. Orthogonality must be established so that the two hybrid orbitals can be involved in separate covalent bonds. The inner product of orthogonal orbitals must be zero and computing the inner product of the constructed hybrids gives the following calculation.

The s orbital is normalized and so the inner product ⟨ s | s ⟩ = 1. Also, the s orbital is orthogonal to the pi and pj orbitals, which leads to two terms in the above equaling zero. Finally, the last term is the inner product of two normalized functions that are at an angle of ωij to each other, which gives cos ωij by definition. However, the orthogonality of bonding orbitals demands that 1 + √λiλj cos ωij = 0, so we get Coulson's theorem as a result:[16][17]

This means that the four s and p atomic orbitals can be hybridised in arbitrary directions provided that all of the coefficients λ satisfy the above condition pairwise to guarantee the resulting orbitals are orthogonal.

Bent's rule, that central atoms direct orbitals of greater p character towards more electronegative substituents, is easily applicable to the above by noting that an increase in the λi coefficient increases the p character of the s + √λipi hybrid orbital. Thus, if a central atom A is bonded to two groups X and Y and Y is more electronegative than X, then A will hybridise so that λX < λY. More sophisticated theoretical and computation techniques beyond Bent's rule are needed to accurately predict molecular geometries from first principles, but Bent's rule provides an excellent heuristic in explaining molecular structures.

Henry Bent originally proposed his rule in 1960 on empirical grounds, but a few years later it was supported by molecular orbital calculations by Russell Drago.[11]

See also

References

- Weinhold, F.; Landis, C. L. (2005), Valency and Bonding: A Natural Donor-Acceptor Perspective (1st ed.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-83128-4

- Bent, H. A. (1961), "An appraisal of valence-bond structures and hybridization in compounds of the first-row elements", Chem. Rev., 61 (3): 275–311, doi:10.1021/cr60211a005

- Foster, J. P.; Weinhold, F. (1980), "Natural hybrid orbitals", J. Am. Chem. Soc., 102 (24): 7211–7218, doi:10.1021/ja00544a007

- Alabugin, I. V.; Bresch, S.; Gomes, G. P. (2015). "Orbital Hybridization: a Key Electronic Factor in Control of Structure and Reactivity". J. Phys. Org. Chem. 28 (2): 147–162. doi:10.1002/poc.3382.

- Alabugin, I. V.; Bresch, S.; Manoharan, M. (2014). "Hybridization Trends for Main Group Elements and Expanding the Bent's Rule Beyond Carbon: More than Electronegativity". J. Phys. Chem. A. 118 (20): 3663–3677. Bibcode:2014JPCA..118.3663A. doi:10.1021/jp502472u. PMID 24773162.

- Pauling, L. (1931), "The nature of the chemical bond. Application of results obtained from the quantum mechanics and from a theory of paramagnetic susceptibility to the structure of molecules", J. Am. Chem. Soc., 53 (4): 1367–1400, doi:10.1021/ja01355a027

- Slater, J. C. (1931), "Directed Valence in Polyatomic Molecules", Phys. Rev., 37 (5): 481–489, Bibcode:1931PhRv...37..481S, doi:10.1103/PhysRev.37.481

- Coulson, C. A. (1961), Valence (2nd ed.), Oxford: Clarendon Press

- Walsh, A. D. (1947), "The properties of bonds involving carbon", Discuss. Faraday Soc., 2: 18–25, doi:10.1039/DF9470200018

- Weinhold, F.; Landis, Clark R. (2012). Discovering Chemistry with Natural Bond Orbitals. Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley. pp. 67–68. ISBN 9781118119969.

- Huheey, James E. (1983). Inorganic Chemistry (3rd ed.). p. 230. ISBN 0-06-042987-9.

- Muller, N.; Pritchard, D. E. (1959), "C13 in Proton Magnetic Resonance Spectra. I. Hydrocarbons", J. Chem. Phys., 31 (3): 768–771, Bibcode:1959JChPh..31..768M, doi:10.1063/1.1730460

- Muller, N.; Pritchard, D. E. (1959), "C13 in Proton Magnetic Resonance Spectra. II. Bonding in Substituted Methanes", J. Chem. Phys., 31 (6): 1471–1476, Bibcode:1959JChPh..31.1471M, doi:10.1063/1.1730638

- Bent, H. A. (1960), "Distribution of atomic s character in molecules and its chemical implications", J. Chem. Educ., 37 (12): 616–624, Bibcode:1960JChEd..37..616B, doi:10.1021/ed037p616

- Taft Jr., R. W. (1957), "Concerning the Electron—Withdrawing Power and Electronegativity of Groups", J. Chem. Phys., 26 (1): 93–96, Bibcode:1957JChPh..26...93T, doi:10.1063/1.1743270

- Coulson, C. A. (1961), Valence (2nd ed.), Oxford: Clarendon Press, pp. 203–5 Non–equivalent hybrids

- Pfennig, Brian W. (2015). "10". Principles of Inorganic Chemistry. John Wiley and Sons. Retrieved 11 August 2023.

Equation (10.11) is also known as Coulson's theorem