Bent Pyramid

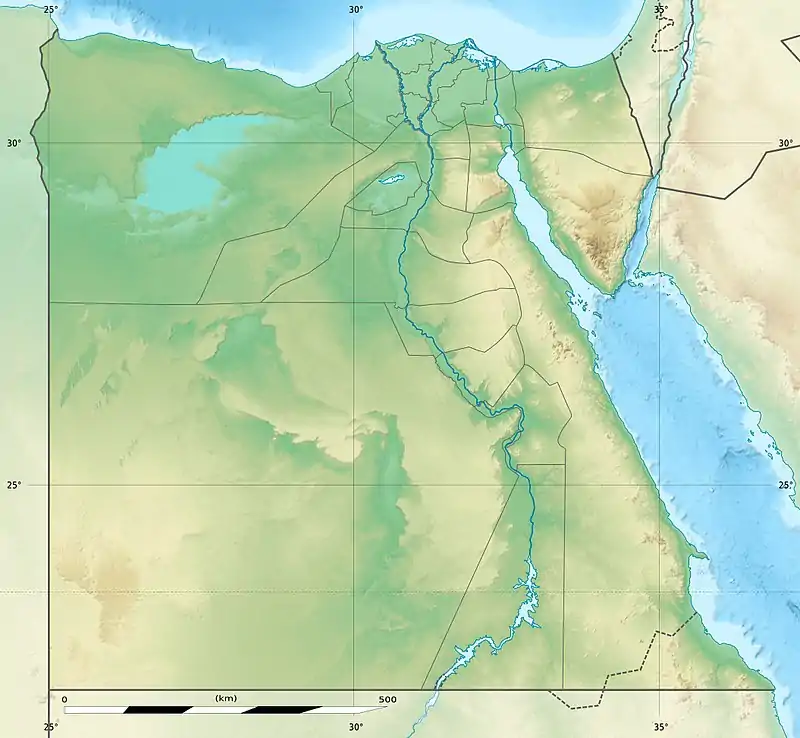

The Bent Pyramid is an ancient Egyptian pyramid located at the royal necropolis of Dahshur, approximately 40 kilometres (25 mi) south of Cairo, built under the Old Kingdom Pharaoh Sneferu (c. 2600 BC). A unique example of early pyramid development in Egypt, this was the second pyramid built by Sneferu.

| Bent Pyramid | |

|---|---|

Sneferu's bent pyramid at Dahshur, an early experiment in true pyramid building | |

| Sneferu | |

| Coordinates | 29°47′25″N 31°12′33″E |

| Ancient name | |

| Constructed | c. 2600 BC (4th dynasty) |

| Type | Bent pyramid |

| Material | Limestone |

| Height | |

| Base | |

| Volume | 1,237,040 cubic metres (43,685,655 cu ft)[2] |

| Slope |

|

Location within Egypt | |

The Bent Pyramid rises from the desert at a 54-degree inclination, but the top section (above 47 metres [154 ft]) is built at the shallower angle of 43 degrees, lending the pyramid a visibly 'bent' appearance.[4]

Overview

Archaeologists now believe that the Bent Pyramid represents a transitional form between step-sided and smooth-sided pyramids. It has been suggested that due to the steepness of the original angle of inclination the structure may have begun to show signs of instability during construction, forcing the builders to adopt a shallower angle to avert the structure's collapse.[5] This theory appears to be borne out by the fact that the adjacent Red Pyramid, built immediately afterwards by the same pharaoh, was constructed at an angle of 43 degrees from its base. This fact also contradicts the theory that at the initial angle the construction would take too long because Sneferu's death was nearing, so the builders changed the angle to complete the construction in time. In 1974, Kurt Mendelssohn suggested the change of the angle to have been made as a stability precaution in reaction to a catastrophic collapse of the Meidum Pyramid while it was still under construction.[6] The reason why Sneferu abandoned the Meidum Pyramid and its Step Pyramid may have been a change in ideology. The royal tomb was no longer considered as a staircase to the stars; instead, it was served as a symbol of the solar cult and of the primeval mound from which all life sprang.[7]

It is also unique amongst the approximately ninety pyramids to be found in Egypt, in that its original polished limestone outer casing remains largely intact. British structural engineer Peter James attributes this to larger clearances between the parts of the casing than used in later pyramids; these imperfections would work as expansion joints and prevent the successive destruction of the outer casing by thermal expansion.[8]

The ancient formal name of the Bent Pyramid is generally translated as (The)-Southern-Shining-Pyramid, or Sneferu-(is)-Shining-in-the-South. In July 2019, Egypt decided to open the Bent Pyramid for tourism for the first time since 1965.[9] Tourists are able to reach two 4600-year-old chambers through a 79-metre (259 ft) narrow tunnel built from the northern entrance of the pyramid. The 18-metre-high (59 ft) "side pyramid", which is assumed to have been built for Sneferu's wife Hetepheres will also be accessible. It is the first time this adjacent pyramid has been opened to the public since its excavation in 1956.[10][11][12][13]

Interior passages

The Bent Pyramid has two entrances, one fairly low down on the north side, to which a substantial wooden stairway has been built for the convenience of tourists. The second entrance is high on the west face of the pyramid. Each entrance leads to a chamber with a high, corbelled roof; the northern entrance leads to a chamber that is below ground level, the western to a chamber built in the body of the pyramid itself. A hole in the roof of the northern chamber (accessed today by a high and rickety ladder 15 m (50 ft) long) leads via a rough connecting passage to the passage from the western entrance.

The western entrance passage is blocked by two stone blocks which were not lowered vertically, as in other pyramids, but slid down 45° ramps to block the passage. One of these was lowered in antiquity and a hole has been cut through it, the other remains propped up by a piece of ancient cedar wood. The connecting passage referenced above enters the passage between the two portcullises.

Causeway

A causeway leads from the Bent Pyramids' northeast toward the pyramid with the valley temple. The causeway was paved with limestone blocks and had a low limestone wall on each side. In fact, there may have been a second causeway that lead down to a dock or landing stage, but there is no excavation that can prove this assumption yet.[14]

Pyramid temple

On the east side of the pyramid there are the fragmentary remains of the pyramid temple. Like the pyramid temple of the Meidum pyramid, there are two stelae behind the temple, though of these only stumps remain. There is no trace of inscription to be seen. The temple remains are fragmentary but it is presumed to be similar to that of the Meidum temple.

Satellite pyramid

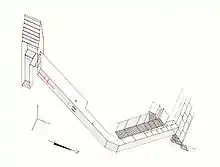

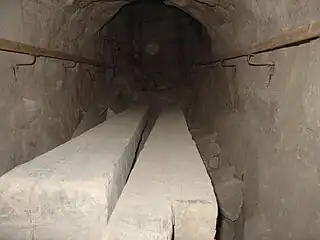

A satellite pyramid, suggested by some Egyptologists to have been built to house the pharaoh's ka, is located 55 metres (180 ft) south of the Bent Pyramid.[15] The satellite pyramid originally measured 26 metres (85 ft) in height and 52.80 metres (173.2 ft) in length, with faces inclining 44°30'.[15][note 1] The structure is made of limestone blocks, relatively thick, arranged in horizontal rows and covered with a layer of fine limestone from Tura. The burial chamber is accessible from a descending corridor with its entrance located 1.10 metres (3 ft 7 in) above the ground in the middle of the north face.[15] The corridor, inclined at 34°, originally measured 11.60 metres (38.1 ft) in length.[15] A short horizontal passage connects the corridor with an ascending corridor, inclined at 32° 30', leading up to the chamber.[15]

The design of the corridors is similar to the one found in the Great Pyramid of Giza, where the Grand Gallery takes up the place of the ascending corridor. The corridor leads up to the burial chamber (called this despite that it most probably never contained any sarcophagus).[16] The chamber, located in the center of the pyramid, has a corbel vault ceiling and contains a four metres deep shaft, probably dug by treasure hunters, in the southeast part of the chamber.[16]

Like the main pyramid, the satellite had its own altar with two stelae located at the eastern side.[17]

Man-made landscape

As the first geometrically "true" pyramid in the world, the Bent Pyramid shows its uniqueness not only from the method of construction but also manifests through the surrounding landscape. Nicole Alexanian and Felix Arnold, two distinguished German archeologists, provided a new insight toward the meaning and function for the Bent Pyramid in their book named The complex of the Bent Pyramid as a landscape design project. They noticed that the sites of the Bent Pyramid sits aside in the middle of a pristine desert area instead of fertile area near the Nile River like all the other pyramids. After a long period detailed investigation, they believed the landscape surrounding the Bent Pyramid is in fact man-made.[18] When the archaeologists observed the landscape closely, the plateau of the pyramid seemed leveled artificially and nearby escarpment and trenches were all made by human beings. Moreover, there were a few traces left indicating a build-up of garden enclosure. The impact of humans on the landscape is also represented by the presence of a wadi channel connecting the Bent Pyramid to a harbor, which shows a distinct difference between the southern and northern side of the channel. It shows a substantial difference in level with regards to the finding. The slope of southern wadi channel seemed to have been rectified when the archaeologists compared it to the natural and twisted northern side. Arne Ramisch supported this idea by providing evidence that displays a low correlation of fraternal patterns of channel and natural topography in the environs, which is southern side of wadi, of the Bent Pyramid.[19]

The purpose of this man-made construction might hold mythical meaning and ritual function. Based on available evidence, garden enclosure and water basins both are the counterparts of funeral rites which indicates a regular practice of rituals at Dahshur.[20] However, there is also the implication that the garden closure helped to create a satisfactory living environment in the desert.[21] Other than that, the leveled plateau, the quarrying trenches on the western and southern sides of the pyramid, and the nearby smaller tombs cooperate together to emphasize the monumentality of the Bent Pyramid, aiding by its long distance from the surrounding structures. These features represent the imprinting social hierarchy in the creation of this landscape, which furthermore represents the power of Egyptian King at that time. Alexanian and Arnold describes this construction in a concise phrase: an artificial mountain erected within an artificial landscape.

Gallery

The 11 degree change in angle

The 11 degree change in angle Wooden beams in the pyramid

Wooden beams in the pyramid The satellite pyramid

The satellite pyramid Entrance of the satellite pyramid

Entrance of the satellite pyramid Descending passageway of the Bent Pyramid's Satellite pyramid.

Descending passageway of the Bent Pyramid's Satellite pyramid. Entrance to the Bent Pyramid

Entrance to the Bent Pyramid View of the outer door inside the pyramid

View of the outer door inside the pyramid Vertical passage to the interior of the pyramid

Vertical passage to the interior of the pyramid.JPG.webp) Stairways inside the pyramid

Stairways inside the pyramid The edge of the pyramid plateau is well visible. It shows how it is isolated from the cultivated area.

The edge of the pyramid plateau is well visible. It shows how it is isolated from the cultivated area. Descending passageway of the Bent Pyramid after installation of wooden staircase.

Descending passageway of the Bent Pyramid after installation of wooden staircase. View of the Black pyramid and the Bent pyramid.

View of the Black pyramid and the Bent pyramid.

Passageway leading up to the tomb of Sneferu

Passageway leading up to the tomb of Sneferu

See also

Notes

- Nearly identical to the inclination of the Red Pyramid

Footnotes

- Verner 2001d, p. 174.

- Lehner 2008, p. 17.

- Verner 2001d, p. 462.

- Verner, Miroslav, The Pyramids - Their Archaeology and History, Atlantic Books, 2001, ISBN

- History Channel, Ancient Egypt - Part 3: Greatest Pharaohs 3150 to 1351 BC, History Channel, 1996, ISBN

- Mendelssohn, Kurt (1974), The Riddle of the Pyramids, London: Thames & Hudson Recent conclusions rather speak against a connection between the change in slope and structural defects. It is rather doubtful that a reduction in weight was a relevant criterion for a structure of almost closed mass. The early decision against the 60° inclination initially envisaged rather suggests that geometric aspects were the decisive factor in the gradient change. Following the assumption of tangential construction ramps inclined up to 10° as the simplest form of ramp, the fact edge lengths became smaller as the height increased made it increasingly difficult to keep the gradient low. This could be compensated for by reducing the ramp width to around 3 m, which was sufficient for pairs of train crews, but even for such narrow ramps the geometric volume could not provide enough space when the gradient was too steep. Models and abstract calculations were not possible in that time. It must therefore have become clear to the construction managers halfway up that ramp structures would not be feasible when maintaining this gradient. In fact, all completed pyramids (first the Red, then the Great Pyramid) never exceeded the maximum gradient of 43°. (ref. Tom Leiermann: The Building of the Pyramids: Reconstruction of the Ramps. In: Global Journal of Archaeology and Anthropology. Band 12, Nr. 4, 2023, ISSN 2575-8608 )

- Kinnaer, Jacques. "Bent Pyramid at Dashur". The Ancient Egyptian Site. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- James, Peter (May 2013). "New Theory on Egypt's Collapsing Pyramids". structuremag.org. National Council of Structural Engineers Associations. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- "Egypt's Bent Pyramid opens to visitors". BBC News. 13 July 2019.

- "'Bent' pyramid: Egypt opens ancient oddity for tourism". The Guardian. 2019-07-15. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 2023-02-28. Retrieved 2023-03-06.

- "Egypt opens Sneferu's 'Bent' Pyramid in Dahshur to public". Reuters. 2019-07-13. Archived from the original on 2019-07-14. Retrieved 2019-07-15.

- "Egyptian 'bent' pyramid dating back 4,600 years opens to public". The Independent. 2019-07-13. Retrieved 2019-07-15.

- "Egypt's 4,600yo Bent Pyramid opens to the public after more than half a century". ABC News. 2019-07-14. Retrieved 2019-07-15.

- Hill, Jenny. "Dashur: Bent Pyramid of Sneferu". Ancient Egypt Online. Jenny Hill. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- Maragioglio & Rinaldi 1963, pp. 74–78

- Fakhry 1961

- Maragioglio & Rinaldi 1963, p. 80

- Alexanian, Nicole; Arnold, Felix (2016). Martina Ullmann (ed.). The Complex of the Bent Pyramid as a Landscape Design Project. 10. Ägyptologische Tempeltagung: Ägyptische Tempel zwischen Normierung und Individualität: 29-31 August 2014. Munich, Germany: Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 1–16. JSTOR j.ctvc5pfjr.5. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- Alexanian, Nicole; Bebermeier, Wiebke; Blaschta, Dirk; Ramisch, Arne (2012). "The Pyramid Complexes and the Ancient Landscape of Dashur/Egypt". ETopoi. Journal for Ancient Studies. 3: 131-133. ISSN 2192-2608. Archived from the original on 13 July 2020. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- W. Kalser, Diekleine Hebseddarstellung im Sonnenheiligtum des Niuserre, in: G. HAENY(Hg.), Aufsatze zum 70. Geburtstag von Herbert Ricke, Beitrage zur agyptischen Bauforschung und Altertumskunde 12, Wiesbanden 1971, 87-105, pl. 4.

- Alexanian, Nicole; Arnold, Felix (2016). Martina Ullmann (ed.). The Complex of the Bent Pyramid as a Landscape Design Project. 10. Ägyptologische Tempeltagung: Ägyptische Tempel zwischen Normierung und Individualität: 29-31 August 2014. Munich, Germany: Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 1–16. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

References

- Fakhry, Ahmed (1961). The Monuments of Sneferu at Dahshur. General Organization for Government.

- Lehner, Mark (2008). The Complete Pyramids. New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-28547-3.

- Maragioglio, Vito & Rinaldi, Celeste (1963). L'Architettura delle Piramidi Menfite, parte III. Artale.

- Verner, Miroslav (2001d). The Pyramids: The Mystery, Culture and Science of Egypt's Great Monuments. New York: Grove Press. ISBN 978-0-8021-1703-8.