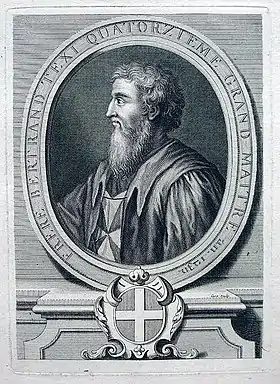

Bertrand de Thessy

Bertrand de Thessy (died 1231 at Acre), also known as Bertrand of Thercy, was the fifteenth Grand Master of the Knights Hospitaller, serving between 1228 and 1230 or 1231.[1] He succeeded Guérin de Montaigu upon his death on 1 March 1228. Thessy was either from France or Italy, most likely the former. He was succeeded by Guérin Lebrun.[2]

Frederick II

Bertrand de Thessy's election to the responsibility of Grand Master corresponds to the arrival of Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II in the Holy Land. He embarked at Brindisi on 28 June 1228 and, after a stay in Cyprus from July 21 to September 3 to settle the suzerainty on the island for his benefit, landed at Acre on September 7. Frederick had been excommunicated by pope Gregory IX on 29 September 1227 and had prohibited all Christians from all places where Frederick would set foot, asking the Latin patriarch Gérold of Lausanne to promulgate the sentence of excommunication and three military orders to deny him obedience. Thessy thus refused to recognize him as king of Jerusalem, followed in this regard by Pedro de Montaigu, master of the Templars. The Teutonic Knights under Hermann of Salza, unused to disobedience vis-à-vis a German sovereign, fully supported the emperor.[3]

The Sixth Crusade

Frederick led a small contingent south from Acre and in November 1228 took charge of Jaffa. He was followed by the Templars and the Hospitallers one day's journey back, respecting the pope's position. They also viewed Frederick's thusly engaging with the sultan al-Kamil in the midst of the troops negatively. Lacking a strong army, the emperor was not looking for confrontation but for negotiation which ended up being successful on 18 February 1229, resulting in Jerusalem, Bethlehem and Nazareth being returned to the Franks. This ten-year, six-month and ten-day peace treaty was to begin on 24 February 1229. In fact, it was on the parchment it was written than in reality, as the Muslims kept key strategic points. The emperor had achieved his goal, to return to Jerusalem and be crowned as king, which he did on 18 March 1229. Frederick ended up crowning himself, as no one wished to violate the papal orders. Returning to Acre in the face of hostility, he embarked for Italy on 1 May 1229.[4]

Thessy, together with the Templars and the patriarch Gérold of Lausanne, representing the clergy of the Holy Land, refused to accept the treaty as the Principality of Antioch and the County of Tripoli were excluded from the considerations. No effort had been made to protect the interests of these Crusader states. A further problem was the decision to leave two Christian shrines to the Muslims––the Temple of Our Lord (Mosque of Omar) and the Temple of Solomon (al-Aqsa Mosque).[5] In August 1229, Gregory IX issued a papal bull to the Latin patriarch directing that the Hospitallers maintain jurisdiction over the Teutonic Knights, in punishment for their following Frederick.[6]

After the Crusade

The Hospitallers and Templars took advantage of the fact that they were excluded from the treaty and, in the fall of 1229, led a successful incursion into the north of the country against the Muslims of the fortress of Montferrand and a disastrous expedition to Hama in July and August 1230. Hope returned when Frederick obtained from the pope relief from his excommunication on 28 August 1230 at the Treaty of Ceprano, and he returned to the Hospitallers and the Templars the goods confiscated in Sicily. Thessy died at Acre in 1231. He was succeeded by Guérin Lebrun as early as 1230 and at most at some time prior to 1 May 1231.[7]

See also

References

- Bernard de Thessy Archived 2021-12-03 at the Wayback Machine. Masters of the Hospitallers (2020).

- Josserand 2009, p. 984, Bertrand de Thessy.

- Delaville Le Roulx 1904, pp. 160–166, Bertrand de Thessy et Guérin.

- Van Cleve 1969, p. 452.

- Van Cleve 1969, pp. 454–458.

- Phillips, Walter Alison (1911). "St John of Jerusalem, Knights of the Order of the Hospital of". In Encyclopædia Britannica. 24. (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 12–19.

- Demurger 2013, p. 539.

Bibliography

- Abulafia, David (1992). Frederick II: A Medieval Emperor. Oxford University Press. ISBN 019508040-8.

- Asbridge, Thomas (2012). The Crusades: The War for the Holy Land. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-84983-688-3.

- Barker, Ernest (1923). The Crusades. World's manuals. Oxford University Press, London.

- Bronstein, Judith (2005). The Hospitallers and the Holy Land: Financing the Latin East, 1187-1274. Boydell Press. ISBN 9781843831310.

- Delaville Le Roulx, Joseph (1904). Les Hospitaliers en Terre Sainte et à Chypre (1100-1310). E. Leroux, Paris.

- Demurger, Alain (2013). Les Hospitaliers, De Jérusalem à Rhodes 1050-1317. Tallandier, Paris. ISBN 979-1021000605.

- Giles, Keith R. (1987). The Emperor Frederick II's Crusade, 1215 – c. 1231 (PDF). Ph.D Dissertation, Keele University.

- Harot, Eugène (1911). Essai d'armorial des grands maîtres de l'Ordre de Saint-Jean de Jérusalem. Collegio araldico.

- Josserand, Philippe (2009). Prier et combattre, Dictionnaire européen des ordres militaires au Moyen Âge. Fayard, Paris. ISBN 978-2213627205.

- Lock, Peter (2006). The Routledge Companion to the Crusades. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203389638. ISBN 0-415-39312-4.

- Murray, Alan V. (2006). The Crusades—An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-862-4.

- Nicholson, Helen J. (2001). The Knights Hospitaller. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 978-1843830382.

- Röhricht, Reinhold (1884). Annales de Terre Sainte, 1095-1291. E. Leroux, Paris.

- Runciman, Steven (1954). A History of the Crusades, Volume Three: The Kingdom of Acre and the Later Crusades. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521347723.

- Setton, Kenneth M. (1969). A History of the Crusades. Six Volumes. University of Wisconsin Press.

- Tyerman, Christopher (2006). God's War: A New History of the Crusades. Belknap Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02387-1.

- Van Cleve, Thomas C. (1969). The Crusade of Frederick II (PDF). A History of the Crusades (Setton), Volume II.

- Vann, Theresa M. (2006). Order of the Hospital. The Crusades––An Encyclopedia, pp. 598–605.

- Weiler, Björn K. U. (2006). Crusade of Emperor Frederick II (1227–1229). The Crusades––An Encyclopedia, pp. 313–315.

External links

- Bertrand de Thessy. French Wikipedia.

- Liste des grands maîtres de l'ordre de Saint-Jean de Jérusalem. French Wikipedia.

- Eugène Harot, Essai d’armorial des Grands-Maîtres de l’Ordre de Saint Jean de Jérusalem.

- Seals of the Grand Masters. Museum of the Order of St John.

- Charles Moeller, Hospitallers of St. John of Jerusalem. Catholic Encyclopedia (1910) 7. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Knights of the Order of the Hospital of St John of Jerusalem, Encyclopædia Britannica. 20. (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 12–19.