Bet hedging (biology)

Biological bet hedging occurs when organisms suffer decreased fitness in their typical conditions in exchange for increased fitness in stressful conditions. Biological bet hedging was originally proposed to explain the observation of a seed bank, or a reservoir of ungerminated seeds in the soil.[1] For example, an annual plant's fitness is maximized for that year if all of its seeds germinate. However, if a drought occurs that kills germinated plants, but not ungerminated seeds, plants with seeds remaining in the seed bank will have a fitness advantage. Therefore, it can be advantageous for plants to "hedge their bets" in case of a drought by producing some seeds that germinate immediately and other seeds that lie dormant. Other examples of biological bet hedging include female multiple mating,[2] foraging behavior in bumble bees,[3] nutrient storage in rhizobia,[4] and bacterial persistence in the presence of antibiotics.[5]

Overview

Categories

There are three categories (strategies) of bet-hedging: "conservative" bet-hedging, "diversified" bet-hedging, and "adaptive coin flipping."

Conservative bet hedging

In conservative bet hedging, individuals lower their expected fitness in exchange for a lower variance in fitness. The idea of this strategy is for an organism to "always play it safe" by using the same successful low-risk strategy regardless of environmental conditions.[6] An example of this would be an organism producing clutches with a constant egg size that may not be optimal for any environmental condition, but result in the lowest overall variance.[6]

Diversified bet hedging

In contrast to conservative bet hedging, diversified bet hedging occurs when individuals lower their expected fitness in a given year while also increasing the variance of survival between offspring. This strategy uses the idea of not "putting all of your eggs in a basket."[6] Individuals implementing this strategy actually invest in several different strategies at once, resulting in low variation in long-term success. This could be demonstrated by a clutch of eggs of different sizes, each optimal for one potential environment of the offspring. While this means that offspring specialized for another environment are less likely to survive to adulthood, it also protects against the possibility of no offspring surviving to the next year.[6]

Adaptive coin flipping

An individual using this type of bet hedging chooses what strategy to use based on a prediction of what the environment will be like. Organisms using this form of bet hedging make these predictions and select strategies annually. For example, an organism may produce clutches of different egg sizes from year to year, increasing variation in offspring success between clutches.[6] Unlike conservative and diversified bet hedging strategies, adaptive coin flipping isn't concerned with minimizing the variation in fitness between years.

Evolution

To determine if a bet hedging allele is favored, the long-term fitness of each allele must be compared. Particularly in highly variable environments where bet hedging is likely to evolve, long-term fitness is best measured using the geometric mean,[7] which is multiplicative instead of additive like the arithmetic mean. The geometric mean is highly sensitive to small values. Even rare occurrences of zero fitness for a genotype result in it having an expected geometric mean of zero. This makes it appropriate for circumstances where a single genotype may have variable fitness depending on environmental circumstances.

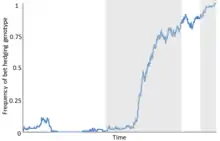

Bet hedging is understood to be a mode of response to environmental change.[8] Adaptations that allow organisms to survive in fluctuating environmental conditions provide an evolutionary advantage. While a bet hedging trait may not be optimal for any one environment, this is outweighed by the benefits of higher fitness across a variety of environments. Therefore, bet hedging alleles tend to be favored in more variable environments. In order for a bet hedging allele to spread, it must persist in the typical environment through genetic drift long enough for alternative environments, in which the bet hedger has an advantage over genotypes adapted to the previous environment, to occur. Over many subsequent environmental alternations, selection may sweep the allele to fixation.[9]

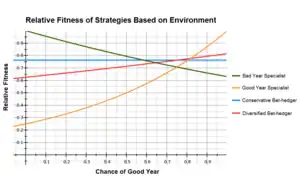

A common example used when describing bet hedging is comparing the arithmetic and geometric fitness between specialist and bet hedging genotypes.[10][11] The table below shows the relative fitness of four phenotypes in 'good' and 'bad' years and their respective means if 'good' years occur 75% of the time and 'bad' years 25% of the time.

| Phenotype | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year Type | Good Year

Specialist |

Bad Year

Specialist |

Conservative

Bet hedger |

Diversified

Bet hedger |

| Good | 1.0 | 0.63 | 0.763 | 0.815 |

| Bad | 0.25 | 1.0 | 0.763 | 0.625 |

| Arithmetic mean | 0.813 | 0.723 | 0.763 | 0.768 |

| Geometric mean | 0.707 | 0.707 | 0.763 | 0.763 |

The good year specialist has the highest fitness during a good year but does very poorly during a bad year, while the reverse is true for a bad year specialist. The conservative bet hedger does equally well in all years and the diversified bet hedger in this example uses the two specialist strategies each 50% of the time; they perform better than the conservative bet hedger in good years, but worse during a bad year.

In this example, fitness is approximately equal within the specialist and bet hedger strategies, with the bet hedgers having a significantly higher fitness than the specialists. While the good year specialist' has the highest arithmetic mean, the bet hedging strategies are still preferred due to their higher geometric mean.

It is also important to realize that the fitness of any strategy is dependent on a large number of factors, such as the ratio of good to bad years and its relative fitness between good and bad years. Small changes in the strategies or environment having a large impact on which is optimal. In the above example, the diversified bet hedger outweighs the conservative bet hedger if it uses the good year specialist strategy more often. In contrast, if the relative fitness of the good year specialist was 0.35 in a bad year, it becomes the optimal strategy.

In organisms

Prokarya

Experiments in bet hedging using prokaryotic model organisms provide some of the most simplified views of the evolution of bet hedging. As bet hedging involves a stochastic switching between phenotypes across generations,[12] prokaryotes are able to display this phenomenon quite nicely due to their ability to reproduce quickly enough to track evolution in a single population over a short period of time. This rapid rate of reproduction has allowed for the study of bet hedging in labs through experimental evolution models. These models have been used to deduce the evolutionary origins of bet hedging.

Within prokarya, there are a multitude of bet hedging examples. In one example, the bacterium Sinorhizobium meliloti stores carbon and energy in a compound known as poly-3-hydroxybutyrate (PHB) in order to withstand carbon-deficient environments. When starved, S. meliloti populations begin to display bet hedging by forming two non-identical daughter cells during binary fission. The daughter cells display either low PHB levels or high PHB levels, which are better suited to short and long-term starvation, respectively. It has been reported that the low-PHB must compete effectively for resources in order to survive, whereas the high-PHB cells can survive for over a year without food. In this example, the PHB phenotype is being ‘bet-hedged’, as the survivability of the offspring largely depends on their environment, where only one phenotype is likely to survive under specific conditions.[13]

Another example of bet hedging arises in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. In a given population of this bacteria, persister cells exist with the ability to arrest their growth, which leaves them unaffected by dramatic changes to the environment. Once the persister cells grow to form another population of its species, which may or may not be antibiotic resistant, they will produce both cells with normal cell growth and another population of persisters to continue this cycle as the case may be. The ability to switch between the persister and normal phenotype is a form of bet-hedging.[14]

Prokaryotic persistence as a method of bet hedging is thus of importance to the field of medicine due to bacterial persistence. Because bet hedging is designed to produce genetically diverse offspring randomly in order to survive catastrophe, it is difficult to develop treatments for bacterial infections, as bet hedging may ensure the survival of its species within its host, heedless to the antibiotic.

Eukarya

Eukaryotic bet hedging models, unlike prokaryotic models, tend to be used to study more complex evolutionary processes. In the context of eukaryotes, bet hedging is best used as a way to analyze complex environmental influences affecting the selective pressures underlying the principle of bet hedging. However, because Eukarya is a broad category, this section has been subdivided into kingdoms Animalia, Plantae, and Fungi.

Vertebrates

In example, West Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) have been hypothesized to have major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-dependent mating systems, which have been shown in other species to be important for determining disease resistance among offspring. Namely, there is evidence that selection for increased MHC diversity is a strong influence on mate choice, where it is thought that individuals are more likely to mate with individuals whose MHC is less similar to their own in order to produce variable offspring. In accordance with the bet hedging model, it has been found that the reproductive success of mating pairs of Atlantic salmon is environmentally dependent, where certain MHC constructs are only advantageous under specific environmental circumstances. Thus, this supports the evidence that MHC diversity is crucial for the long-term reproductive success of the parents, as the tradeoff for an initial decrease in short-term reproductive fitness is mediated by the survival of a few of their offspring in a variable environment.[15]

A second example among vertebrates is the marsupial species Sminthopsis macrour, which use a torpor strategy in order to reduce their metabolic rate to survive environmental changes. Reproductive hormone cycles have been shown to mediate the timing of torpor and reproduction, and in mice have been shown to mediate this process entirely, heedless to the environment. In the marsupial species, however, an adaptive coin flipping mechanism is employed where neither torpor nor reproduction are affected by manipulation of hormones, suggesting that this marsupial species makes a more active decision about when to use torpor that is better-suited to the uncertain environment in which it lives.[16]

Invertebrates

Many invertebrate species are known to exhibit various forms of bet hedging. Diaptomus sanguineus, an aquatic crustacean species found in many ponds of the Northeast United States, is one of the most well-studied examples of bet hedging. This species uses a form of diversified bet hedging called germ banking, in which emergence timing among offspring from a single clutch is highly variable. This reduces the potential costs of a catastrophic event during a particularly vulnerable time in offspring development. In Diaptomus sanguineus, germ banking occurs when parents produce dormant eggs prior to annual environmental shifts that yield increased risk for developing offspring. For example, in temporary ponds, Diaptomus sanguineus production of dormant eggs peaks just before the annual dry season in June when ponds levels decrease. In permanent ponds, dormant egg production increases in March, just before an annual increase in feeding activity of sunfish.[17] This example demonstrates that germ banking may take different forms within a species depending on the environmental risk presented. Bet hedging through variable egg hatching patterns are seen in other crustaceans as well.[18][19]

Invertebrate bet-hedging has also been observed in the mating systems of some species of spider. Female sierra dome spiders (Linyphia litigiosa) are polyandrous, mating with secondary males in order to compensate for uncertainty regarding the quality of the primary mate. Primary male mates are considered to be of higher fitness than secondary males, as primary mates must overcome intrasexual fighting prior to mating with a female, while secondary male mates are chosen through female choice. Scientists believe multiple paternity has evolved in response to virgin insemination by low quality secondary male mates who have not undergone selection through intrasexual fighting. Females have developed a mechanism for sperm precedence to retain control over offspring paternity and increase offspring fitness. Further examination of female genitalia has supported this hypothesis. The sierra dome spider exhibits this behavior as a form of genetic bet hedging, reducing the risk of producing low quality offspring and contracting venereal disease.[20] This form of bet hedging is notably different than most other forms of bet hedging, as it has not arisen in response to environmental conditions, but rather it has arisen as a result of the species mating system.

Fungi

Bet hedging is employed in fungi similarly to bacteria, but in fungi, it is more complex. This phenomenon is beneficial to fungi, but in some cases, it has harmful effects on humans, illustrating that bet hedging has clinical importance. One study suggests that bet hedging may even contribute to the failure of chemotherapy in cancer due to mechanisms similar to that of bet hedging used in fungi.[21]

One way fungi use bet hedging is by displaying different colony morphologies when grown on agar plates.[22] This variation allows for colonies with different morphologies, including resistances that allow them to survive, to thrive and reproduce in different conditions or environments. As a result, fungal infections may be more difficult to treat if bet hedging is involved. For example, pathogenic strains of yeast like Candida albicans or Candida glabrata using this strategy will resist treatments. These fungi are known to cause an infection known as candidiasis.

While bet hedging in fungi is important, not much is known about the mechanisms for the different strategies employed by different species. Researchers have studied S. cerevisiae to determine the mechanism of bet hedging in this species.[22] It was determined that in S. cerevisiae, variation exists in the distribution of growth rates among yeast micro-colonies and that slow growth is a predictor of resistance to heat. Tsl1 is one gene that was determined as a factor in this resistance. The abundance of this gene was shown to correlate with heat and stress resistance, and thus survival of the yeast micro-colonies under harsh conditions by using bet hedging. This illustrates that by using bet hedging, pathogenic strains of this yeast that are harmful to humans are more difficult to treat.

A group of researchers studied another way bet hedging is used by looking at the ascomycete fungus Neurospora crassa.[23] It was observed that this species produces ascospores with variation in their dormancy because non-dormant ascospores can be killed by heat, but dormant ascospores will survive. The only con is that it will take longer for the dormant ascospores to be germinated.

Plantae

Plants provide simple examples for studying bet hedging in wildlife, allowing for field studies but without as many confounding factors as animals. Studying closely related plant species can help us understand more about the circumstances under which bet hedging evolves.

The classic example of bet hedging, delayed seed germination,[1] has been extensively studied in desert annuals.[24][25][26] One four-year field study[24] found that populations in historically worse (drier) environments had lower germination rates. They also found a large range of germination dates and flexibility in germination for drier populations when exposed to rain, a phenomenon known as phenotypic plasticity. Other studies of desert annuals[25][26] have also found a relationship between temporal variation and lower germination rates. One of these studies[26] also found the density of seeds in the seed bank to affect germination rates.

Bet hedging through a seed bank has also been implicated in the persistence of weeds. One study[27] of twenty weed species showed that the percentage of viable seeds after 5 years increased with soil depth, and germination rates decreased with soil depth (although specific numbers varied between species). This indicates that weeds will engage in bet hedging at higher rates in circumstances where the costs of bet hedging are lower.

In bet-hedging species, seed dormancy appears correlated "to a higher polyphenol (flavonoid) content in seed coats, resulting in darker morphs (Gianella et al., 2021)."[28] In barrel medick (Medicago truncatula) four flavonoid controlling genes, in addition to peroxidases and thio/peroxiredoxins, "have been associated with differential dormancy along an aridity gradient (Renzi et al., 2020)."[28]

Collectively, these findings do provide evidence for bet hedging in plants, but also show the importance of competition and phenotypic plasticity that simple bet hedging models often ignore.

Archaea

Thus far, research on bet hedging involving species in the domain Archaea hasn't been easily accessible.

Viruses

Bet hedging has been used to explain the latency of Herpes viruses. The Varicella Zoster Virus, for instance, causes chickenpox at first infection and can cause shingles many years after the original infection. The delay with which shingles emerges has been explained as a form of bet hedging.[29]

References

- Cohen, Dan (1966-09-01). "Optimizing reproduction in a randomly varying environment". Journal of Theoretical Biology. 12 (1): 119–129. Bibcode:1966JThBi..12..119C. doi:10.1016/0022-5193(66)90188-3. PMID 6015423.

- Yasui, Yukio (2001-12-01). "Female multiple mating as a genetic bet-hedging strategy when mate choice criteria are unreliable". Ecological Research. 16 (4): 605–616. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1703.2001.00423.x. ISSN 1440-1703. S2CID 34683958.

- Burns, James G. (2008). "Diversity of speed-accuracy strategies benefits social insects". Current Biology. 18 (20): R953–R954. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2008.08.028. PMID 18957249. S2CID 16696224.

- Ratcliff, William C.; Denison, R. Ford (2010-10-12). "Individual-Level Bet Hedging in the Bacterium Sinorhizobium meliloti". Current Biology. 20 (19): 1740–1744. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2010.08.036. PMID 20869244. S2CID 16856229.

- Kussell, E. (31 January 2005). "Bacterial Persistence: A Model of Survival in Changing Environments". Genetics. 169 (4): 1807–1814. doi:10.1534/genetics.104.035352. PMC 1449587. PMID 15687275.

- Olofsson, H.; Ripa, J.; Jonzen, N. (27 May 2009). "Bet-hedging as an evolutionary game: the trade-off between egg size and number". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 276 (1669): 2963–2969. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.0500. PMC 2817213. PMID 19474039.

- Dempster, Everett R. (1955-01-01). "Maintenance of Genetic Heterogeneity". Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology. 20: 25–32. doi:10.1101/SQB.1955.020.01.005. ISSN 0091-7451. PMID 13433552.

- Simons, Andrew M. (2011-06-07). "Modes of response to environmental change and the elusive empirical evidence for bet hedging". Proceedings: Biological Sciences. 278 (1712): 1601–1609. doi:10.1098/rspb.2011.0176. ISSN 1471-2954. PMC 3081777. PMID 21411456.

- King, Oliver D.; Masel, Joanna (2007-12-01). "The evolution of bet-hedging adaptations to rare scenarios". Theoretical Population Biology. 72 (4): 560–575. doi:10.1016/j.tpb.2007.08.006. PMC 2118055. PMID 17915273.

- Philippi, Tom; Seger, Jon (1989). "Hedging one's evolutionary bets, revisited". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 4 (2): 41–44. doi:10.1016/0169-5347(89)90138-9. PMID 21227310.

- Seger, Jon; Brockmann, H. Jane (1987). "What is bet-hedging?". In Harvey, P. H.; Partridge, L. (eds.). Oxford surveys in evolutionary biology. Vol. 4. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. pp. 182–211.

- Beaumont, H. J. E.; Kost, C.; Rainey, P. B.; Gallie, J.; Ferguson, G. C. (2009). "Experimental evolution of bet hedging". Nature. 462 (7269): 90–93. Bibcode:2009Natur.462...90B. doi:10.1038/nature08504. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-002A-07D3-B. PMID 19890329. S2CID 4369450.

- Ratcliff, W. C.; Denison, R. F. (2010). "Individual-level bet hedging in the bacterium sinorhizobium meliloti". Current Biology. 20 (19): 1740–1744. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2010.08.036. PMID 20869244. S2CID 16856229.

- Veening, J.; Smits, W. K.; Kuipers, O. P. (2008). "Bistability, epigenetics, and bet-hedging in bacteria" (PDF). Annual Review of Microbiology. 62 (1): 193–210. doi:10.1146/annurev.micro.62.081307.163002. PMID 18537474. S2CID 3747871.

- Evans, M. L.; Dionne, M.; Miller, K. M.; Bernatchez, L. (2012). "Mate choice for major histocompatibility complex genetic divergence as a bet-hedging strategy in the atlantic salmon (salmo salar)". Proceedings: Biological Sciences. 279 (1727): 379–386. doi:10.1098/rspb.2011.0909. PMC 3223684. PMID 21697172.

- McAllan, B. M.; Feay, N.; Bradley, A. J.; Geiser, F. (2012). "The influence of reproductive hormones on the torpor patterns of the marsupial sminthopsis macroura: Bet-hedging in an unpredictable environment". General and Comparative Endocrinology. 179 (2): 265–276. doi:10.1016/j.ygcen.2012.08.024. PMID 22974513.

- Evans, Margaret E K; Dennehy, John J (2005-12-01). "Germ Banking: Bet‐Hedging and Variable Release from Egg and Seed Dormancy". The Quarterly Review of Biology. 80 (4): 431–451. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.587.7117. doi:10.1086/498282. ISSN 0033-5770. PMID 16519139. S2CID 2343748.

- Radzikowski, J. (2013-07-01). "Resistance of dormant stages of planktonic invertebrates to adverse environmental conditions". Journal of Plankton Research. 35 (4): 707–723. doi:10.1093/plankt/fbt032. ISSN 0142-7873.

- Hakalahti, Teija; Häkkinen, Heli; Valtonen, E. Tellervo (2004-01-01). "Ectoparasitic Argulus coregoni (Crustacea: Branchiura) Hedge Their Bets: Studies on Egg Hatching Dynamics". Oikos. 107 (2): 295–302. doi:10.1111/j.0030-1299.2004.13213.x. JSTOR 3548212.

- Watson, Paul J. (1991-02-01). "Multiple paternity as genetic bet-hedging in female sierra dome spiders, Linyphia litigiosa (Linyphiidae)". Animal Behaviour. 41 (2): 343–360. doi:10.1016/S0003-3472(05)80486-5. S2CID 53152243.

- Meadows, Robin (8 May 2012). "Yeast Survive by Hedging Their Bets". PLOS Biology. 10 (5): e1001327. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001327. PMC 3348148. PMID 22589702.

- Levy, Sasha F.; Ziv, Naomi; Siegal, Mark L. (8 May 2012). "Bet Hedging in Yeast by Heterogeneous, Age-Correlated Expression of a Stress Protectant". PLOS Biology. 10 (5): e1001325. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001325. PMC 3348152. PMID 22589700.

- Graham, Jeffrey K.; Smith, Myron L.; Simons, Andrew M. (22 July 2014). "Experimental evolution of bet hedging under manipulated environmental uncertainty in Neurospora crassa". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 281 (1787): 20140706. doi:10.1098/rspb.2014.0706. PMC 4071552. PMID 24870047.

- Clauss, M. J.; Venable, D. L. (2000-02-01). "Seed Germination in Desert Annuals: An Empirical Test of Adaptive Bet Hedging". The American Naturalist. 155 (2): 168–186. doi:10.1086/303314. ISSN 0003-0147. PMID 10686159. S2CID 4439415.

- Philippi, Thomas (1993-09-01). "Bet-Hedging Germination of Desert Annuals: Variation Among Populations and Maternal Effects in Lepidium lasiocarpum". The American Naturalist. 142 (3): 488–507. doi:10.1086/285551. ISSN 0003-0147. PMID 19425988. S2CID 498615.

- Gremer, Jennifer R.; Venable, D. Lawrence (2014-03-01). "Bet hedging in desert winter annual plants: optimal germination strategies in a variable environment". Ecology Letters. 17 (3): 380–387. doi:10.1111/ele.12241. ISSN 1461-0248. PMID 24393387.

- Roberts, H. A.; Feast, Patricia M. (1972-12-01). "Fate of Seeds of Some Annual Weeds in Different Depths of Cultivated and Undisturbed Soil". Weed Research. 12 (4): 316–324. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3180.1972.tb01226.x. ISSN 1365-3180.

- Huss, Jessica C.; Gierlinger, Notburga (June 2021). "Functional packaging of seeds". New Phytologist: International Journal of Plant Science. 230 (6): 2154–2163. doi:10.1111/nph.17299. PMC 8252473. PMID 33629369.

- Stumpf, Michael P. H.; Laidlaw, Zoe; Jansen, Vincent A. A. (2002). "Herpes Viruses Hedge Their Bets". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 99 (23): 15234–15237. Bibcode:2002PNAS...9915234S. doi:10.1073/pnas.232546899. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 137573. PMID 12409612.

External links

Media related to Bet hedging (biology) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Bet hedging (biology) at Wikimedia Commons