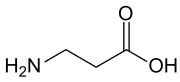

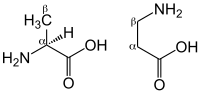

β-Alanine

β-Alanine (or beta-alanine) is a naturally occurring beta amino acid, which is an amino acid in which the amino group is attached to the β-carbon (i.e. the carbon two carbon atoms away from the carboxylate group) instead of the more usual α-carbon for alanine (α-alanine). The IUPAC name for β-alanine is 3-aminopropanoic acid. Unlike its counterpart α-alanine, β-alanine has no stereocenter.

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

β-Alanine | |

| Systematic IUPAC name

3-Aminopropanoic acid | |

| Other names

3-Aminopropionic acid | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.003.215 |

| EC Number |

|

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties[1][2] | |

| C3H7NO2 | |

| Molar mass | 89.093 g/mol |

| Appearance | white bipyramidal crystals |

| Odor | odorless |

| Density | 1.437 g/cm3 (19 °C) |

| Melting point | 207 °C (405 °F; 480 K) (decomposes) |

| 54.5 g/100 mL | |

| Solubility | soluble in methanol. Insoluble in diethyl ether, acetone |

| log P | -3.05 |

| Acidity (pKa) |

|

| Hazards | |

| Occupational safety and health (OHS/OSH): | |

Main hazards |

Irritant |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

LD50 (median dose) |

1000 mg/kg (rat, oral) |

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references | |

Biosynthesis and industrial route

In terms of its biosynthesis, it is formed by the degradation of dihydrouracil and carnosine. β-Alanine ethyl ester is the ethyl ester which hydrolyses within the body to form β-alanine.[4] It is produced industrially by the reaction of ammonia with β-propiolactone.[5]

Sources for β-alanine includes pyrimidine catabolism of cytosine and uracil.

Biochemical function

β-Alanine residues are rare. It is a component of the peptides carnosine and anserine and also of pantothenic acid (vitamin B5), which itself is a component of coenzyme A. β-alanine is metabolized into acetic acid.

Precursor of carnosine

β-Alanine is the rate-limiting precursor of carnosine, which is to say carnosine levels are limited by the amount of available β-alanine, not histidine.[6] Supplementation with β-alanine has been shown to increase the concentration of carnosine in muscles, decrease fatigue in athletes, and increase total muscular work done.[7][8] Simply supplementing with carnosine is not as effective as supplementing with β-alanine alone since carnosine, when taken orally, is broken down during digestion to its components, histidine and β-alanine. Hence, by weight, only about 40% of the dose is available as β-alanine.[6]

Because β-alanine dipeptides are not incorporated into proteins, they can be stored at relatively high concentrations. Occurring at 17–25 mmol/kg (dry muscle),[9] carnosine (β-alanyl-L-histidine) is an important intramuscular buffer, constituting 10-20% of the total buffering capacity in type I and II muscle fibres. In carnosine, the pKa of the imidazolium group is 6.83, which is ideal for buffering.[10]

Receptors

Even though much weaker than glycine (and, thus, with a debated role as a physiological transmitter), β-alanine is an agonist next in activity to the cognate ligand glycine itself, for strychnine-sensitive inhibitory glycine receptors (GlyRs) (the agonist order: glycine ≫ β-alanine > taurine ≫ alanine, L-serine > proline).[11]

β-alanine has five known receptor sites, including GABA-A, GABA-C a co-agonist site (with glycine) on NMDA receptors, the aforementioned GlyR site, and blockade of GAT protein-mediated glial GABA uptake, making it a putative "small molecule neurotransmitter."[12]

Athletic performance enhancement

There is evidence that β-alanine supplementation can increase exercise and cognitive performance,[13][14][15][16] for some sporting modalities,[17] and exercises within a 0.5–10 min time frame.[18] β-alanine is converted within muscle cells into carnosine, which acts as a buffer for the lactic acid produced during high-intensity exercises, and helps delay the onset of neuromuscular fatigue.[15][19]

Ingestion of β-alanine can cause paraesthesia, reported as a tingling sensation, in a dose-dependent fashion.[16] Aside from this, no important adverse effect of β-alanine has been reported, however, there is also no information on the effects of its long-term usage or its safety in combination with other supplements, and caution on its use has been advised.[13][14] Furthermore, many studies have failed to test for the purity of the supplements used and check for the presence of banned substances.[15]

Metabolism

β-Alanine can undergo a transamination reaction with pyruvate to form malonate-semialdehyde and L-alanine. The malonate semialdehyde can then be converted into malonate via malonate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase. Malonate is then converted into malonyl-CoA and enter fatty acid biosynthesis.[20]

Alternatively, β-alanine can be diverted into pantothenic acid and coenzyme A biosynthesis.[20]

References

- The Merck Index: An Encyclopedia of Chemicals, Drugs, and Biologicals (11th ed.), Merck, 1989, ISBN 091191028X, 196.

- Weast, Robert C., ed. (1981). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (62nd ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. p. C-83. ISBN 0-8493-0462-8..

- Haynes, William M., ed. (2016). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (97th ed.). CRC Press. pp. 5–88. ISBN 978-1498754286.

- Wright, Margaret Robson (1969). "Arrhenius parameters for the acid hydrolysis of esters in aqueous solution. Part I. Glycine ethyl ester, β-alanine ethyl ester, acetylcholine, and methylbetaine methyl ester". Journal of the Chemical Society B: Physical Organic: 707–710. doi:10.1039/J29690000707.

- Miltenberger, Karlheinz (2005). "Hydroxycarboxylic Acids, Aliphatic". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a13_507.

- "Beta-Alanine Supplementation For Exercise Performance". Archived from the original on 20 June 2017. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- Derave W, Ozdemir MS, Harris R, Pottier A, Reyngoudt H, Koppo K, Wise JA, Achten E (August 9, 2007). "Beta-alanine supplementation augments muscle carnosine content and attenuates fatigue during repeated isokinetic contraction bouts in trained sprinters". J Appl Physiol. 103 (5): 1736–43. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00397.2007. PMID 17690198. S2CID 6990201.

- Hill CA, Harris RC, Kim HJ, Harris BD, Sale C, Boobis LH, Kim CK, Wise JA (2007). "Influence of beta-alanine supplementation on skeletal muscle carnosine concentrations and high intensity cycling capacity". Amino Acids. 32 (2): 225–33. doi:10.1007/s00726-006-0364-4. PMID 16868650. S2CID 23988054.

- Mannion, AF; Jakeman, PM; Dunnett, M; Harris, RC; Willan, PLT (1992). "Carnosine and anserine concentrations in the quadriceps femoris muscle of healthy humans". Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 64 (1): 47–50. doi:10.1007/BF00376439. PMID 1735411. S2CID 24590951.

- Bate-Smith, EC (1938). "The buffering of muscle in rigor: protein, phosphate and carnosine". Journal of Physiology. 92 (3): 336–343. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1938.sp003605. PMC 1395289. PMID 16994977.

- Encyclopedia of Life Sciences Amino Acid Neurotransmitters. Jeremy M Henley, 2001 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. doi:10.1038/npg.els.0000010, Article Online Posting Date: April 19, 2001

- Tiedje KE, Stevens K, Barnes S, Weaver DF (October 2010). "Beta-alanine as a small molecule neurotransmitter". Neurochem Int. 57 (3): 177–88. doi:10.1016/j.neuint.2010.06.001. PMID 20540981. S2CID 7814845.

- Quesnele JJ, Laframboise MA, Wong JJ, Kim P, Wells GD (2014). "The effects of beta-alanine supplementation on performance: a systematic review of the literature". Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab (Systematic review). 24 (1): 14–27. doi:10.1123/ijsnem.2013-0007. PMID 23918656.

- Hoffman JR, Stout JR, Harris RC, Moran DS (2015). "β-Alanine supplementation and military performance". Amino Acids. 47 (12): 2463–74. doi:10.1007/s00726-015-2051-9. PMC 4633445. PMID 26206727.

- Hobson, R. M.; Saunders, B.; Ball, G.; Harris, R. C.; Sale, C. (9 December 2016). "Effects of β-alanine supplementation on exercise performance: a meta-analysis". Amino Acids. 43 (1): 25–37. doi:10.1007/s00726-011-1200-z. ISSN 0939-4451. PMC 3374095. PMID 22270875.

- Trexler ET, Smith-Ryan AE, Stout JR, Hoffman JR, Wilborn CD, Sale C, Kreider RB, Jäger R, Earnest CP, Bannock L, Campbell B, Kalman D, Ziegenfuss TN, Antonio J (2015). "International society of sports nutrition position stand: Beta-Alanine". J Int Soc Sports Nutr (Review). 12: 30. doi:10.1186/s12970-015-0090-y. PMC 4501114. PMID 26175657.

- Brisola, Gabriel M P; Zagatto, Alessandro M (2019). "Ergogenic Effects of β-Alanine Supplementation on Different Sports Modalities: Strong Evidence or Only Incipient Findings?". The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 33 (1): 253–282. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000002925. PMID 30431532. S2CID 53441737.

- Bryan Saunders; Kirsty Elliott-Sale; Guilherme G Artioli1; Paul A Swinton; Eimear Dolan; Hamilton Roschel; Craig Sale; Bruno Gualano (2017). "β-alanine supplementation to improve exercise capacity and performance: a systematic review and meta-analysis FREE". British Journal of Sports Medicine. 51 (8): 658–669. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2016-096396. PMID 27797728. S2CID 25496458.

- Guilherme Giannini Artioli; Bruno Gualano; Abbie Smith; Jeffrey Stout; Antonio Herbert Lancha Jr. (June 2010). "Role of beta-alanine supplementation on muscle carnosine and exercise performance". Med Sci Sports Exerc. 42 (6): 1162–73. doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181c74e38. PMID 20479615.

- "KEGG PATHWAY: beta-Alanine metabolism - Reference pathway". www.genome.jp. Retrieved 2016-10-04.