Bhaktapur Durbar Square

Bhaktapur Durbar Square (Nepal Bhasa: 𑐏𑑂𑐰𑐥 𑐮𑐵𑐫𑐎𑐸 Nepali: भक्तपुर दरबार क्षेत्र) is a former royal palace complex located in Bhaktapur, Nepal. It housed the Malla kings of Nepal from 14th to 15th century and the kings of the Kingdom of Bhaktapur from 15th to late 18th century until the kingdom was conquered in 1769. Today, this square is recognised by UNESCO, managed jointly by the Archeological Department of Nepal and Bhaktapur Municipality, and is under heavy restoration due to the damages from the earthquake in 1934 and the recent earthquake of 2015.[1]

| Bhaktapur Durbar Square | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

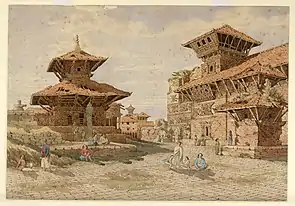

General view of the central part of the square before the 1934 earthquake. | |||||||||||||

| General information | |||||||||||||

| Architectural style | Nepalese Architecture | ||||||||||||

| Location | Bhaktapur, Nepal | ||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 27°40′19″N 85°25′41″E | ||||||||||||

| Construction started | 14th century | ||||||||||||

| Owner | Bhaktapur Municipality | ||||||||||||

| Website | |||||||||||||

| https://bhaktapurmun.gov.np/en | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

The Durbar Square is a generic name for the Malla palace square and can be found in Kathmandu and Patan as well. The one in Bhaktapur was considered the biggest and the grandest among the three during its independency but now many of the buildings that once occupied the square has been lost to the frequent earthquakes.[2] During its height, Bhaktapur Durbar Square contained 99 courtyards but today hardly 15 of these courtyards remain.[2] The square has lost most of its buildings and courtyards to frequent earthquakes, particularly those in 1833 and 1934 and only a few of the damaged buildings were restored.

Detailed information and pictures can be found in : https://www.bhaktapur.com/

Layout

The Durbar Square of Bhaktapur once occupied a very large area and was surrounded by a stone wall.[3] After, Bhaktapur was defeated by the Gorkhali forces, the palace square fell into disrepair and the earthquakes of 1833 and 1934 reduced the square to its present size.[4] The former palace ground have been used as government offices, schools and private houses.[4] Like the ones of Kathmandu and Patan, Bhaktapur Durbar Square contains various temples, palaces and courtyards all of which were built in the traditional Nepalese architecture.[5]

In general, the Durbar Square is divided into three parts based on its location:

Kvathū Lyākū

Literally meaning 'lower part of the royal palace' in Nepal Bhasa, the Kvathū Lyākū is bounded by the Khaumā district in the west and the Vyāsi district in the north.[6] This part contains the Lyākū Dhvākhā gate, the ruins of Basantapūra and Chaukota palace and a replica of the Char Dham of India.[6] The Lyākū Dhvākhā gate was likely built during the Rana period and today is the main entrance to the Durbar Square of Bhaktapur.

Basantapūra palace of Bhaktapur

The most important building of this part of the square was the Basantapūra rājakula, formerly a nine storey palace at the western end of Bhaktapur Durbar Square.[7] The building was originally commissioned by King Jagat Prakasha Malla of Bhaktapur in mid 17th century and later was damaged in the earthquake of 1681.[7] His grandson, Bhupatindra Malla had it repaired in May 1702 when he also inaugurated the sculptures of Ugracaṇdī and Ugrabhairava, the destructive forms of Devi and Shiva placed near the entrance of the palace.[7] These statues were likely carved by a group of artisans led by Tulasi Lohankarmi, who just a year before also carved a ten foot statue of Devi for the Nyatapola temple.[8] The palace once covered a large area and was the largest and tallest palace of Nepal before being partially destroyed in the earthquake of 1833, as seen in the watercolour done by Oldfield in 1856 which shows the partially destroyed palace in the deep right part of the painting.[7] In fact, the painting by Oldfield is one of only two known visual depictions of the palace, the other one being a fresco at a restrictive courtyard in the palace square, where only priests are allowed and photography is prohibited and such is the only publicly available image of the now destroyed palace.[8] In 1769, after the defeat of Malla rulers of Bhaktapur by the Gorkhalis, the buildings within the former palace square were left in a state of disrepair.[7] As such frequent earthquakes in the 19th and 20th century destroyed much of the square including the Basantapūra rājakula palace, which after being partially destroyed in the earthquke of 1833 was demolished by Dhir Shumsher Rana who established a kitchen garden in its area.[7] Later in 1947, a government school was shifted to the area which still stands there.[7]

During the Malla period when the Basantapūra palace still existed it occupied a large area and contained stadiums, swimming pools, extensive gardens, a sort of auditorium for music and dance and was also reported to contain entertainment for queens and royal concubines.[7] In fact, Jagat Prakasha Malla, the commissioner of the palace named it as "nakhachhe tavagola kwatha", meaning "a large fort meant for festivals" in Nepal Bhasa.[9] It becomes clear that the palace was made mostly for entrainment purposes rather than living one.[7] Similarly, after the Gorkhali forces defeated Bhaktapur in 1769, they looted most of the valuables present royal square, including Basantapūra palace from which maximum loot was taken which matches its Malla dynasty depiction of being decorated with expensive materials.[7] Similarly, a contemporary document from 1830 puts the height of this palace at around 23.3 meters.[9] The Basantapūra palace is cited as an inspiration for the Nautalle Durbar or the Basantapūra Durbar in Kathmandu, commissioned by Prithvi Narayan Shah after his victory over the Kathmandu Valley.[7][9]

Today, most of the components of the Basantapūra palace has been lost to time. It is said that Dhurba Shusmer Rana, the magistrate for Bhaktapur in the late 19th century used the wooden tympanum of its entrance gate, which was commissioned by Bhupatindra Malla during its restoration, and its windows as firewood.[7] Similarly, In 1947 when a government school was shifted to its area, the school building was made right on top of the foundation of the old palace and since the school is still present in the area, excavation work has not been done.[7] Today, the only remaining part of the palace are the two large statues of guardian lions and a pair of statue of Ugracaṇdī and Ugrabhairava, the destructive forms of Devi and Shiva which was inaugurated by Bhupatindra Malla in May 1702 while the palace was being restored.[9] Today, these statues are a tourist attraction in Bhaktapur and the local government describes them as "a masterpieces of the medieval period".[10] Recently, a hoax has surfaced about these statues which says that Bhupatindra Malla had cut off the hands of the artisan who carved the statue of Devi so that he may not replicate it in Kantipur or Lalitpur and then he went on and carved the Bhairava statue with his feet after which his feet was also cut off.[8] While it was true that there was a fierce competition between the three cities, there are no historical records of the artisan's hand being cut off. It is likely that these statues were carved by a group led by Tulasi Lohankarmi who just a year before carved a ten foot statue of Devi for the Nyatapola temple.[8] For his work, Tulasi was rewarded with a tola of gold along with his wage when the temple was inaugurated.[8]

Chaukota palace

Not much is known about this palace, which once existed east of the Basantapura palace. The palace was likely demolished during the restoration work done in 1856 and commissioned by Dhir Shumsher Rana.[6] Two artworks by Henry Ambrose Oldfield depict the palace. However, the antiquity of this building is not properly known. This palace is mentioned in an inscription during the reign of Jitamitra Malla (reign 1672–1696), so it must date from before his reign.[6] Similarly, during the Battle of Bhaktapur, it is said that Ranajit Malla took shelter in this palace as the invading Gorkhali armies started to enter the palace square.[6] The word word Chaukota literally means "four forts" in Sanskrit and as such the palace seems to have functioned as a fort with a tall observatory on its rooftop and was likely functioned as an arms storage as well.[6] Recently, while doing minor construction work in the area, a small part of a sculpture was found, which along with figurines of deities also contained a small inscription with the name of Jagajjyoti Malla.[6]

Char Dham and the Krishna temple

The replica of the Char Dham of India was commissioned by Yaksha Malla in the 15th century with the intention of giving old, weak and handicapped citizens the satisfaction of worship the Char Dham without having to go on a pilgrimage to these sites.[11] The temples within the Char Dham includes terracotta temple of Kedarnath (akin to the temple of same name in Uttarakhand) and Badrinanth (akin to temple of same name in Uttarakhand, domed temple of Ramesvar (akin to Ramanathaswamy Temple) and Nepalese pagoda styled temple of Jagannath (akin to the temple in Puri).[6] Among these the Jagannath temple was the largest and was destroyed in the earthquake of 1833 after which a shed like structure was built.[8] It is presently being restored to its original architecture.[8] In 1667, the Gopinath Krishna temple was consecrated in the Nepalese style akin to the Dwarkadhish Temple which replaces Kedarnath as one of the Char Dham in Indian traditions.[12] Similarly, all five of these temples were restored in the 18th century by Bhupatindra Malla to its present state.[12] It is believed that each of the four temples stood on the direction of the four corners of the roof of the Gopinath Krishna temple.[13] While it is true for three of the temples, the domed temple of Ramesvar is joined with the floor plan of the Jagannath temple, although it is said to be the product of renovation works in 1856.[8]

Major attractions

Nge Nyapa Jhya Laaykoo (55 window palace)

.jpg.webp)

The major attraction of this place are:

'The Palace of Fifty-five Windows( 𑐒𑐾𑐒𑐵𑐥𑐵 𑐗𑑂𑐫𑑅 𑐮𑐵𑐫𑐎𑐹 Nge Nyapa Jhya Laaykoo, Devanagari: ङेङापा झ्यः लायकू, ) was built during the reign of the Malla King Bhupetindra Malla who ruled from 1696 to 1722 AD and was not complete until 1754 AD during the reign of his son Ranajit Malla.[14]

Vatsala Temple

.jpg.webp)

Directly in front of the palace and beside the king's statue and next to the Taleju Bell is the Vatsala Devi Temple. This Shikhara style temple is completely constructed in sandstone and is built upon a three-stage plinth, and has similarities to the Krishna temple of Patan. It is dedicated to Vatsala Devi, a form of the goddess Durga. The temple was originally built by King Jitamitra Malla in 1696 A.D. The structure that can be seen today, however, is reconstructed by King Bhupatindra Malla and dates back to the late 17th or early 18th century. Behind the temple is a water source called dhunge dhara and next to it stands the Chayslin Mandap.[15] It was most famous for its silver bell, known to local residents as "the bell of barking dogs" as when it was rung, dogs in the vicinity barked and howled. The colossal bell was hung by King Ranjit Malla in 1737 AD and was used to sound the daily curfew. It was rung every morning when goddess Taleju was worshiped. Despite the Temple being completely demolished by the 2015 Gorkha earthquake, the bell remains intact.

Pashupatinath Temple:

The holy god Shiva temple, the mini Pashupati, is believed to be built right in front of the palace after a Bhadgaun king dreamed of it.[16]

Statue of Bhupatindra Malla

The Statue of King Bhupatindra Malla in the act of worship can be seen on a column facing the palace. Of the square's many statues, this is considered to be the most magnificent.

Siddhi Lakshmi Temple

This Sikhara style temple dedicated to the tantric Goddess Siddhi Lakshmi was built in the 17th century. Statues of various creatures like camels, rhinos, horses and some mythical creatures guard the entrance to this temple.

Nyatapola Temple

Nyatapola in Newari language means five stories - the symbolic of five basic elements. This is the biggest and highest pagoda of Nepal ever built with such architectural perfection and artistic beauty. The temple's foundation is said to be made wider than its base. The temple is dedicated to the goddess Shiddhilaxmi. Those statues lined up on the 2 sides of the staircase are built as guardians of the temple and the residing goddess, which we can see in five layers from the base of temple. It is said that it took three generations to complete that temple.

Bhairava Nath Temple

The Bhairab Nath Temple is dedicated to Bhairava, the most fierce manifestation of Lord Shiva.

Lun Dhwākhā (Golden Gate)

"Lun Dhwākhā", Devanagari:लुँ ध्वाखा, Prachalit: 𑐮𑐸𑑃 𑐢𑑂𑐰𑐵𑐏𑐵, (The Golden Gate)" is said to be the most beautiful and richly molded specimen of its kind in the entire world. The door is surmounted by a figure of the Hindu goddess Kali and Garuda (mythical griffin) and attended by two heavenly nymphs. It is embellished with monsters and other Hindu mythical creatures of marvelous intricacy. Percy Brown, an eminent English art critic and historian, described the Golden Gate as "the most lovely piece of art in the whole Kingdom; it is placed like a jewel, flashing innumerable facets in the handsome setting of its surroundings." The gate was erected by King Ranjit Malla and is the entrance to the main courtyard of the palace of fifty-five windows.[16] The Luṁ dhvākā or the Golden gate which serves as an entrance to the inner courtyards of the former royal palace was constructed between 1751 and 1754 by Subhākara, Karuṇākara and Ratikara.[17] The project was initially planned in 1646 by Jagajjyoti Malla who brought two goldsmiths, Guṇasiṃhadeva and Mānadeva Nivā from Lalitpur but the project was postponed, presumably due to lack of gold.[17] It wasn't until 1751, after getting the funds from Ranajit Malla, that their descendants Subhākara, Karuṇākara and Ratikara began the work finishing it in 1754.[17] Today, it is considered one of the most important works of Nepalese art.

Lion's Gate(𑐮𑐵𑐫𑐎𑐹 𑐢𑑂𑐰𑐵𑐎𑐵)

The magnificent and beautiful gate was built by artisans whose hands were said to have been severed upon completion by the envious Bhadgaun king so that no more of such masterpieces could be reproduced.[16]

Simhadhwaka Durbar:

This palace built by King Bhupatindra Malla in the 17th century houses the National Art Museum which is a great collection of Medieval and Licchvai arts. This palace was named after the statues of a pair of lions guarding its entrance. There are also two large statues of the Hindu god Narsimha.

Temples

Erotic elephants temple — On the left just before the entrance way to the square is a hiti (water fountain). A few steps before that but on the other side of the road, just 100m before the entrance way, is a tiny double-roofed Shiva-Parvati Temple with some erotic carvings on its struts. One of these shows a pair of copulating elephants, in the missionary position: Kisi (elephant) Kamasutra.[15]

Ugrachandi and Ugrabhairab — Near the main gate at the west end, one can admire a pair of multiple-armed statues of the terrible god Ugrabhairab and his counterpart Ugrachandi, the fearsome manifestation of Shiva's consort Parvati. The statues date back to 1701 A.D. and it is said that the unfortunate sculptor had his hands cut off afterward, to prevent him from duplicating his masterpieces. Ugrachandi has eighteen arms holding weapons, and she is in the position of casually killing a (Buffalo) demon. Bhairab has twelve arms and both god and goddess are garlanded with necklaces of human heads.

Rameshwar Temple — The first temple one notices on the right of the gate is Rameshwar, in front of Gopi Nath Temple which is a Gum Baja style. It is an open shrine with four pillars and it is dedicated to Shiva. The name Rameshwar means that Shiva is the lord of Rama, since Rama had to worship Shiva to expiate the sin of killing Ravana who was a Brahmin.[15]

Badrinath Temple — A small temple west of the Gopi Nath Temple locally known as Badri Narayan is dedicated to Vishnu and Narayan.[15]

.jpg.webp)

Gopi Nath Temple — Two roofed pagoda style is the Gopi Nath Temple, attached to Rameshwar Temple that houses the three deities Balaram, Subhadra and Krishna. It is difficult to see the deities as the door remains mostly closed. The temple is also known as Jagannath, which is another form taken by Vishnu. Dwarka, also known as the Krishna Temple, houses three deities, left to right: Satyabhama, Krishna, and Radha. Their images are carved in stone. In the month of Mangsir (November/December), the deities are placed in a palanquin and taken around the city.[15]

Kedarnath Temple — The terracotta made Shikara style temple is the Kedarnath (Shiva) Temple.[15]

Hanuman Statue — The entrance to the National Art Gallery is flanked by the figure of Hanuman, the monkey god, who appears in Tantric form as the four armed Hanuman Bhairab. Hanuman is worshiped for strength and the devotion.[15]

Taduchhen Bahal:

Taduchhen Bahal or Ta:duchhen also known as Chaturvarna Mahavihara is a Buddhist temple built by King Raya Malla in NS 611(1429 AD) located on the eastern side of the square.

Impact of earthquakes

The Durbar Square was severely damaged by the earthquake in 1934 and hence appears more spacious than the others, in Kathmandu and Patan.[18]

Originally, there were 99 courtyards attached to this place, but now only 6 remain. Before the 1934 earthquake, there were 3 separate groups of temples. Currently, the square is surrounded by buildings that survived the quake.[18]

On 25 April 2015, another major earthquake damaged many buildings in the square. The main temple in Bhaktapur's square lost its roof, while the Vatsala Devi temple, known for its sandstone walls and gold-topped pagodas, was also demolished.[19] In total, 116 historical and cultural

monuments were damaged.[20]

Gallery

Chyasilin Mandap

Chyasilin Mandap

- Landscape view of main area

Bhaktapur Durbar Square

Bhaktapur Durbar Square

Siddhi Laxmi Temple

Siddhi Laxmi Temple

Nyathpola

Nyathpola Nyathpola

Nyathpola Ancient statue of goddess Durga

Ancient statue of goddess Durga

References

Citation

- Bhaktapur Durbar Square nepalandbeyonhlooArchived January 8, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- Vaidya 2002, p. 2.

- Vaidya 2002, p. 3.

- Vaidya 2002, p. 1.

- "Bhaktapur Durbar Square | Rubin Museum of Art". rubinmuseum.org. Retrieved 2022-06-26.

- Vaidya 2002, p. 32.

- Munakarmi, Lilabhakta (1998). "भक्तपुरको वसन्तपुर दरबार" (PDF). The Journal of Newar Studies. Oregon, United States: International Nepal Bhasa Sevā Samiti. 2: 57–59.

- Pawn, Anil; Dhaubhadel, Om (21 June 2022). "Talk about Bhaktapur Durbar Square with Om Prasad Dhaubadel". Bhaktapur.com (in Nepali).

- Vaidya 2002, p. 26.

- "The excellent stone images of Ugrachandi and Bhairava – Bhaktapur Municipality". Bhaktapur.com. 21 June 2021. Retrieved 2022-09-09.

- Shrestha, Purushottam Lochan (6 February 2022). "भक्तपुरका असुरक्षित अभिलेख– ३". Majdoor (in Nepali).

- orientalarchitecture.com. "Gopinath Krishna Temple, Bhaktapur, Nepal". Asian Architecture. Retrieved 2022-09-10.

- "Badrinath temple; one of the Char Dham temples of Bhaktapur". Bhaktapur.com. Retrieved 2022-09-10.

- "Nge Nyapa Jhya Laaykoo to be re-opened". Newa issues. Archived from the original on 2019-02-04. Retrieved 2019-02-03.

- Bhaktapur Durbar Square Archived 2015-11-19 at the Wayback Machine, btdc.com.np. Retrieved 27 October 2015

- Bhaktapur Durbar Square. aghtrekking.com, Retrieved 27 October 2015

- Shrestha, Purushottam Lochan (June 1998). "Suvarṇadvāra". Bhaktapur (in Nepali). No. 127. Bhaktapur Municipality. pp. 11–16.

- Woodhatch, Tom (1999). Nepal Handbook (2nd ed.). Bath: Footprint Handbooks. ISBN 9781900949446. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

9781900949446.

- "Nepal's Kathmandu Valley landmarks flattened by quake". BBC News. 26 April 2015. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- Suji, Manoj (2020). "Discourse of post-earthquake heritage reconstruction: A case study of Bhaktapur Municipality" (PDF). Annual Conference of Social Science Baha, Kathmandu.

Bibliography

- Vaidya, Tulasī Rāma (2002). Bhaktapur Rajdarbar. Centre for Nepal and Asian Studies, Tribhuvan University. ISBN 978-99933-52-17-4.

- Shrestha, Purushottam Lochan (2021). "Bhaktapurakā vatsalā mandira haru". Nṛtya vatsalā mandira purnanirmāna (in Nepali). Bhaktapur Municipality: 36–59. ISBN 9789937099110.

Further reading

- von Schroeder, Ulrich. 2019. Nepalese Stone Sculptures. Volume One: Hindu; Volume Two: Buddhist. (Visual Dharma Publications). ISBN 978-3-033-06381-5. Contains SD card with 15,000 digital photographs of Nepalese sculptures and other subjects as public domain.