Parenting

Parenting or child rearing promotes and supports the physical, emotional, social, spiritual and cognitive development of a child from infancy to adulthood. Parenting refers to the intricacies of raising a child and not exclusively for a biological relationship.[1]

The most common caretakers in parenting are the biological parents of the child in question. However, a surrogate parent may be an older sibling, a step-parent, a grandparent, a legal guardian, aunt, uncle, other family members, or a family friend.[2] Governments and society may also have a role in child-rearing or upbringing. In many cases, orphaned or abandoned children receive parental care from non-parent or non-blood relations. Others may be adopted, raised in foster care, or placed in an orphanage. Parenting skills vary, and a parent or surrogate with good parenting skills may be referred to as a good parent.[3]

Parenting styles vary by historical period, race/ethnicity, social class, preference, and a few other social features.[4] Additionally, research supports that parental history, both in terms of attachments of varying quality and parental psychopathology, particularly in the wake of adverse experiences, can strongly influence parental sensitivity and child outcomes.[5][6][7]

Factors that affect decisions

Social class, wealth, culture and income have a very strong impact on what methods of child rearing parents use.[8] Cultural values play a major role in how a parent raises their child. However, parenting is always evolving, as times, cultural practices, social norms, and traditions change. Studies on these factors affecting parenting decisions have shown just that.[9][10]

In psychology, the parental investment theory suggests that basic differences between males and females in parental investment have great adaptive significance and lead to gender differences in mating propensities and preferences.[11]

A family's social class plays a large role in the opportunities and resources that will be available to a child. Working-class children often grow up at a disadvantage with the schooling, communities, and level of parental attention available compared to those from the middle-class or upper-class.[12] Also, lower working-class families do not get the kind of networking that the middle and upper classes do through helpful family members, friends, and community individuals or groups as well as various professionals or experts.[13]

Styles

A parenting style is indicative of the overall emotional climate in the home.[14] Developmental psychologist Diana Baumrind proposed three main parenting styles in early child development: authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive.[15][16][17][18] These parenting styles were later expanded to four to include an uninvolved style. These four styles involve combinations of acceptance and responsiveness, and also involve demand and control.[19] Research[20] has found that parenting style is significantly related to a child's subsequent mental health and well-being. In particular, authoritative parenting is positively related to mental health and satisfaction with life, and authoritarian parenting is negatively related to these variables.[21] With authoritarian and permissive parenting on opposite sides of the spectrum, most conventional modern models of parenting fall somewhere in between.[22] Although it is influential, Baumrind's typology has received significant criticism for containing overly broad categorizations and an imprecise and overly idealized description of authoritative parenting.[23][24][25]

Authoritative parenting

- Described by Baumrind as the "just right" style, it combines medium level demands on the child and a medium level responsiveness from the parents. Authoritative parents rely on positive reinforcement and infrequent use of punishment. Parents are more aware of a child's feelings and capabilities and support the development of a child's autonomy within reasonable limits. There is a give-and-take atmosphere involved in parent-child communication, and both control and support are balanced. Some research has shown that this style of parenting is more beneficial than the too-hard authoritarian style or the too-soft permissive style.[26][27] These children score higher in terms of competence, mental health, and social development than those raised in permissive, authoritarian, or neglectful homes.[28][29] However, Dr. Wendy Grolnick has critiqued Baumrind's use of the term "firm control" in her description of authoritative parenting and argued that there should be clear differentiation between coercive power assertion (which is associated with negative effects on children) and the more positive practices of structure and high expectations.[30]

Authoritarian parenting

- Authoritarian parents are very rigid and strict. High demands are placed on the child, but there is little responsiveness to them. Parents who practice authoritarian-style parenting have a non-negotiable set of rules and expectations strictly enforced and require rigid obedience. When the rules are not followed, punishment is often used to promote and ensure future compliance.[31] There is usually no explanation of punishment except that the child is in trouble for breaking a rule.[32] This parenting style is strongly associated with corporal punishment, such as spanking. A typical response to a child’s question of authority would be, "because I said so." This type of parenting seems to be seen more often in working-class families than in the middle class.[33][34] In 1983, Diana Baumrind found that children raised in an authoritarian-style home were less cheerful, moodier, and more vulnerable to stress. In many cases, these children also demonstrated passive hostility. This parenting style can negatively impact the educational success and career path, while a firm and reassuring parenting style impact positively.[35]

Permissive parenting

- Permissive parenting has become a more popular parenting method for middle-class families than working-class families roughly since the end of WWII.[36] In these settings, a child's freedom and autonomy are highly valued, and parents rely primarily on reasoning and explanation. Parents are undemanding, and thus there tends to be little if any punishment or explicit rules in this parenting style. These parents say that their children are free from external constraints and tend to be highly responsive to whatever it is that the child wants. Children of permissive parents are generally happy but sometimes show low levels of self-control and self-reliance because they lack structure at home.[37] Author Alfie Kohn criticized the study and categorization of permissive parenting, arguing that it serves to "blur the differences between 'permissive' parents who were really just confused and those who were deliberately democratic."[24]

Uninvolved parenting

- An uninvolved or neglectful parenting style is when parents are often emotionally or physically absent.[38] They have little to no expectations from the child and regularly have no communication. They are not responsive to a child's needs and have little to no behavioral expectations. They may consider their children to be "emotionally priceless" and may not engage with them and believe they are giving the child it's personal space.[39] If present, they may provide what the child needs for survival with little to no engagement.[38] There is often a large gap between parents and children with this parenting style. Children with little or no communication with their own parents tend to be victimized by other children and may exhibit deviant behavior themselves.[40][41] Children of uninvolved parents suffer in social competence, academic performance, psychosocial development, and problematic behavior.

Intrusive parenting

- Intrusive parenting is when parents use "parental control and inhibition of adolescents’ thoughts, feelings, and emotional expression through the use of love withdrawal, guilt induction, and manipulative tactics" for protecting them from the possible pitfalls, without knowing it can deprive/disturb the adolescents' development and growth period.[42] Intrusive parents may try to set unrealistic expectations on their children by overestimating their intellectual capability and underestimating their physical capability or developmental capability, like enrolling them into more extracurricular activities or enrolling them into certain classes without understanding their child's passion, and it may eventually lead children not taking ownership of activities or develop behavioral problems. Children, especially adolescents might become victims and be "unassertive, avoid confrontation, being eager to please others, and suffer from low self-esteem."[43] They may compare their children to others, like friends and family, and also force their child to be codependent--to a point where the children feel unprepared when they go into the world. Research has shown that this parenting style can lead to "greater under-eating behaviors, risky cyber behaviors, substance use, and depressive symptoms among adolescents."[44]

Unconditional parenting

- Unconditional parenting refers to a parenting approach that is focused on the whole child, emphasizes working with a child to solve problems, and views parental love as a gift.[24] It contrasts with conditional parenting, which focuses on the child's behavior, emphasizes controlling children using rewards and punishments, and views parental love as a privilege to be earned. The concept of unconditional parenting was popularized by author Alfie Kohn in his 2005 book Unconditional Parenting: Moving from Rewards and Punishments to Love and Reason. Kohn differentiates unconditional parenting from what he sees as the caricature of permissive parenting by arguing that parents can be anti-authoritarian and opposed to exerting control while also recognizing the value of respectful adult guidance and a child's need for non-coercive structure in their lives.

Trustful parenting

- Trustful parenting is a child-centered parenting style in which parents trust their children to make decisions, play and explore on their own, and learn from their own mistakes. Research professor Peter Gray argues that trustful parenting was the dominant parenting style in prehistoric hunter-gatherer societies.[45][46] Gray contrasts trustful parenting with "directive-domineering" parenting, which emphasizes controlling children to train them in obedience (historically involving using child labor to teach subservience to lords and masters), and "directive-protective" parenting, which involves controlling children to protect them from harm.[46] Gray argues that the directive-domineering approach became the predominant parenting style with the spread of agriculture and industry, while the directive-protective approach took over as the dominant approach in the late 20th century.

Practices

A parenting practice is a specific behavior that a parent uses in raising a child. These practices are used to socialize children. Kuppens et al. found that "researchers have identified overarching parenting dimensions that reflect similar parenting practices, mostly by modeling the relationships among these parenting practices using factor analytic techniques."[47] For example, many parents read aloud to their offspring in the hopes of supporting their linguistic and intellectual development. In cultures with strong oral traditions, such as Indigenous American communities and New Zealand Maori communities, storytelling is a critical parenting practice for children.[48][49]

Parenting practices reflect the cultural understanding of children.[50] Parents in individualistic countries like Germany spend more time engaged in face-to-face interaction with babies and more time talking to the baby about the baby. Parents in more communal cultures, such as West African cultures, spend more time talking to the baby about other people and more time with the baby facing outwards so that the baby sees what the mother sees.[50]

Skills and behaviors

Parenting skills and behaviors assist parents in leading children into healthy adulthood and development of the child's social skills. The cognitive potential, social skills, and behavioral functioning a child acquires during the early years are positively correlated with the quality of their interactions with their parents.[51]

According to the Canadian Council on Learning, children benefit (or avoid poor developmental outcomes) when their parents:

- Communicate truthfully about events: Authenticity from parents who explain can help their children understand what happened and how they are involved;

- Maintain consistency: Parents that regularly institute routines can see benefits in their children's behavioral patterns;

- Utilize resources available to them, reaching out into the community and building a supportive social network;

- Take an interest in their child's educational and early developmental needs (e.g., Play that enhances socialization, autonomy, cohesion, calmness, and trust.); and

- Keep open communication lines about what their child is seeing, learning, and doing, and how those things are affecting them.[52][53]

Parenting skills are widely thought to be naturally present in parents; however, there is substantial evidence to the contrary. Those who come from a negative or vulnerable childhood environment frequently (and often unintentionally) mimic their parents' behavior during interactions with their own children. Parents with an inadequate understanding of developmental milestones may also demonstrate problematic parenting. Parenting practices are of particular importance during marital transitions like separation, divorce, and remarriage;[54] if children fail to adequately adjust to these changes, they are at risk of negative outcomes (e.g. increased rule-breaking behavior, problems with peer relationships, and increased emotional difficulties).[55]

Research classifies competence and skills required in parenting as follows:[56]

- Parent-child relationship skills: quality time spent, positive communications, and delighted show of affection.

- Encouraging desirable behavior: praise and encouragement, nonverbal attention, facilitating engaging activities.

- Teaching skills and behaviors: being a good example, incidental teaching, human communication of the skill with role-playing and other methods, communicating logical incentives and consequences.

- Managing misbehavior: establishing firm ground rules and limits, directing discussion, providing clear and calm instructions, communicating and enforcing appropriate consequences, using restrictive tactics like quiet time and time out with an authoritative stance rather than an authoritarian one.

- Anticipating and planning: advanced planning and preparation for readying the child for challenges, finding out engaging and age-appropriate developmental activities, preparing the token economy for self-management practice with guidance, holding follow-up discussions, identifying possible negative developmental trajectories.

- Self-regulation skills: monitoring behaviors (own and children's),[57] setting developmentally appropriate goals, evaluating strengths and weaknesses and setting practice tasks, monitoring and preventing internalizing and externalizing behaviors.

- Mood and coping skills: reframing and discouraging unhelpful thoughts (diversions, goal orientation, and mindfulness), stress and tension management (own and children's), developing personal coping statements and plans for high-risk situations, building mutual respect and consideration between members of the family through collaborative activities and rituals.

- Partner support skills: improving personal communication, giving and receiving constructive feedback and support, avoiding negative family interaction styles, supporting and finding hope in problems for adaptation, leading collaborative problem solving, promoting relationship happiness and cordiality.

Consistency is considered the “backbone” of positive parenting skills and “overprotection” the weakness.[58]

Parent training

Parent psychosocial health can have a significant impact on the parent-child relationship. Group-based parent training and education programs have proven to be effective at improving short-term psychosocial well-being for parents. There are many different types of training parents can take to support their parenting skills. Some groups include Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT), Parents Management Training (PMT), Positive Parenting Program (Triple P), The Incredible Years, and Behavioral and Emotional Skills Training (BEST). [59] PCIT works with both parents and children in teaching skills to interact more positively and productive. PMT is focused for children aged 3-13, in which parents are the main trainee. They are taught skills to help deal with challenging behaviors from their children. Triple P focus on equipping parents with the information they need to increase confidence and self-sufficiency in managing their children's behavior. The Incredible Years focuses in age infancy-age 12, in which they are broken into small-group-based training in different areas. BEST introduces effective behavior management techniques in one day rather than over the course of a few weeks. Courses are offered to families based on effective training to support additional needs, behavioral guidelines, communication and many others to give guidance throughout learning how to be a parent.[60]

Cultural values

Parents around the world want what they believe is best for their children. However, parents in different cultures have different ideas of what is best.[61] For example, parents in hunter–gatherer societies or those who survive through subsistence agriculture are likely to promote practical survival skills from a young age. Many such cultures begin teaching children to use sharp tools, including knives, before their first birthdays.[62] In some Indigenous American communities, child work provides children the opportunity to absorb cultural values of collaborative participation and prosocial behavior through observation and activity alongside adults.[48] These communities value respect, participation, and non-interference, the Cherokee principle of respecting autonomy by withholding unsolicited advice.[63] Indigenous American parents also try to encourage curiosity in their children via a permissive parenting style that enables them to explore and learn through observation of the world.[48]

Differences in cultural values cause parents to interpret the same behaviors in different ways.[61] For instance, European Americans prize intellectual understanding, especially in a narrow "book learning" sense, and believe that asking questions is a sign of intelligence. Italian parents value social and emotional competence and believe that curiosity demonstrates good interpersonal skills.[61] Dutch parents, however, value independence, long attention spans, and predictability; in their eyes, asking questions is a negative behavior, signifying a lack of independence.[61]

Even so, parents around the world share specific prosocial behavioral goals for their children. Hispanic parents value respect and emphasize putting family above the individual. Parents in East Asia prize order in the household above all else. In some cases, this gives rise to high levels of psychological control and even manipulation on the part of the head of the household.[64] The Kipsigis people of Kenya value children who are innovative and wield that intelligence responsibly and helpfully—a behavior they call ng/om.[61] Other cultures, such as Sweden and Spain, value sociable and happiness as well.[61]

Indigenous American cultures

It is common for parents in many Indigenous American communities to use different parenting tools such as storytelling —like myths— Consejos (Spanish for "advice"), educational teasing, nonverbal communication, and observational learning to teach their children important values and life lessons.

Storytelling is a way for Indigenous American children to learn about their identity, community, and cultural history. Indigenous myths and folklore often personify animals and objects, reaffirming the belief that everything possesses a soul and deserves respect. These stories also help preserve the language and are used to reflect certain values or cultural histories.[65]

The Consejo is a narrative form of advice-giving. Rather than directly telling the child what to do in a particular situation, the parent might instead tell a story about a similar situation. The main character in the story is intended to help the child see their decision's implications without directly deciding for them; this teaches the child to be decisive and independent while still providing some guidance.[66]

The playful form of teasing is a parenting method used in some Indigenous American communities to keep children out of danger and guide their behavior. This parenting strategy uses stories, fabrications, or empty threats to guide children in making safe, intelligent decisions. For example, a parent may tell a child that there is a monster that jumps on children's backs if they walk alone at night. This explanation can help keep the child safe because instilling that fear creates greater awareness and lessens the likelihood that they will wander alone into trouble.[67]

In Navajo families, a child's development is partly focused on the importance of "respect" for all things. "Respect" consists of recognizing the significance of one's relationship with other things and people in the world. Children largely learn about this concept via nonverbal communication between parents and other family members.[68] For example, children are initiated at an early age into the practice of an early morning run under any weather conditions. On this run, the community uses humor and laughter with each other, without directly including the child—who may not wish to get up early and run—to encourage the child to participate and become an active member of the community.[68] Parents also promote participation in the morning runs by placing their child in the snow and having them stay longer if they protest.[68]

Indigenous American parents often incorporate children into everyday life, including adult activities, allowing the child to learn through observation. This practice is known as LOPI, Learning by Observing and Pitching In, where children are integrated into all types of mature daily activities and encouraged to observe and contribute in the community. This inclusion as a parenting tool promotes both community participation and learning.[69]

One notable example appears in some Mayan communities: young girls are not permitted around the hearth for an extended period of time, since corn is sacred. Although this is an exception to their cultural preference for incorporating children into activities, including cooking, it is a strong example of observational learning. Mayan girls can only watch their mothers making tortillas for a few minutes at a time, but the sacredness of the activity captures their interest. They will then go and practice their mother's movements on other objects, such as kneading thin pieces of plastic like a tortilla. From this practice, when a girl comes of age, she is able to sit down and make tortillas without having ever received any explicit verbal instruction.[70]

Immigrants in the United States: Ethnic-racial socialization

Due to the increasing racial and ethnic diversity in the United States, ethnic-racial socialization research has gained some attention.[71] Parental ethnic-racial socialization is a way of passing down cultural resources to support children of color's psychosocial wellness.[71] The goals of ethnic-racial socialization are: to pass on a positive view of one's ethnic group and to help children cope with racism.[71] Through a meta-analysis of published research on ethnic-racial socialization, ethnic-racial socialization positively affects psychosocial well-being.[71] This meta-analytic review focuses on research relevant to four indicators of psychosocial skills and how they are influenced by developmental stage, race and ethnicity, research designs, and the differences between parent and child self-reports.[71] The dimensions of ethnic-racial socialization that are considered when looking for correlations with psychosocial skills are cultural socialization, preparation for bias, promotion of mistrust, and egalitarianism.[71]

Ethnic-racial socialization dimensions are defined as follows: cultural socialization is the process of passing down cultural customs, preparation for bias ranges from positive or negative reactions to racism and discrimination, promotion of mistrust conditions synergy when dealing with other races, and egalitarianism puts similarities between races first.[71] Psychosocial competencies are defined as follows: self-perceptions involve perceived beliefs of academic and social capabilities, interpersonal relationships deal with the quality of relationships, externalizing behaviors deal with observable troublesome behavior, and internalizing behavior deals with emotional intelligence regulation.[71] The multiple ways these domains and competencies interact show small correlations between ethnic-racial socialization and psychosocial wellness, but this parenting practice needs further research.[71]

This meta-analysis showed that developmental stages affect how children perceived ethnic-racial socialization.[71] Cultural socialization practices appear to affect children similarly across developmental stages except for preparation for bias and promotion of mistrust which are encouraged for older-aged children.[72][73][74] Existing research shows ethnic-racial socialization serves African Americans positively against discrimination.[74] Cross-sectional studies were predicted to have greater effect sizes because correlations are inflated in these kinds of studies.[75][76][77] Parental reports of ethnic-racial socialization influence are influenced by “intentions,” so child reports tend to be more accurate.[77]

Among other conclusions derived from this meta-analysis, cultural socialization and self-perceptions had a small positive correlation. Cultural socialization and promotion of mistrust had a small negative correlation, and interpersonal relationships positively impacted cultural socialization and preparation for bias.[71] In regard to developmental stages, ethnic-racial socialization had a small but positive correlation with self-perceptions during childhood and early adolescence.[71] Based on study designs, there were no significant differences, meaning that cross-sectional studies and longitudinal studies both showed small positive correlations between ethnic-racial socialization and self-perceptions.[71] Reporter differences between parents and children showed positive correlations between ethnic-racial socialization when associated with internalizing behavior and interpersonal relationships.[71] These two correlations showed a greater effect size with child reports compared to parent reports.[71]

The meta-analysis on previous research shows only correlations, so there is a need for experimental studies that can show causation amongst the different domains and dimensions.[71] Children's behavior and adaptation to this behavior may indicate a bidirectional effect that can also be addressed by an experimental study.[71] There is evidence to show that ethnic-racial socialization can help children of color obtain social-emotional skills that can help them navigate through racism and discrimination, but further research needs to be done to increase the generalizability of existing research.[71]

Across the lifespan

Pre-pregnancy

Family planning is the decision-making process surrounding whether to become parents or not, and when the right time would be, including planning, preparing, and gathering resources. Prospective parents may assess (among other matters) whether they have access to sufficient financial resources, whether their family situation is stable, and whether they want to undertake the responsibility of raising a child. Worldwide, about 40% of all pregnancies are not planned, and more than 30 million babies are born each year as a result of unplanned pregnancies.[78]

Reproductive health and preconception care affect pregnancy, reproductive success, and the physical and mental health of both mother and child. A woman who is underweight, whether due to poverty, eating disorders, or illness, is less likely to have a healthy pregnancy and give birth to a healthy baby than a woman who is healthy. Similarly, a woman who is obese has a higher risk of difficulties, including gestational diabetes.[79] Other health problems, such as infections and iron-deficiency anemia, can be detected and corrected before conception.

Pregnancy and prenatal parenting

During pregnancy, the unborn child is affected by many decisions made by the parents, particularly choices linked to their lifestyle. The health, activity level, and nutrition available to the mother can affect the child's development before birth.[79] Some mothers, especially in relatively wealthy countries, overeat and spend too much time resting. Other mothers, especially if they are poor or abused, may be overworked and may not be able to eat enough, or may not be able to afford healthful foods with sufficient iron, vitamins, and protein, for the unborn child to develop properly.

Newborns and infants

Newborn parenting is where the responsibilities of parenthood begin. A newborn's basic needs are food, sleep, comfort, and cleaning, which the parent provides. An infant's only form of communication is crying, and attentive parents will begin to recognize different types of crying each of which represents different needs such as hunger, discomfort, boredom, or loneliness. Newborns and young infants require feedings every few hours, which is disruptive to adult sleep cycles. They respond enthusiastically to soft stroking, cuddling, and caressing. Gentle rocking back and forth often calms a crying infant, as do massages and warm baths. Newborns may comfort themselves by sucking their thumb or by using a pacifier. The need to suckle is instinctive and allows newborns to feed. Breastfeeding is the recommended method of feeding by all major infant health organizations.[81] If breastfeeding is not possible or desired, bottle feeding is a common alternative. Other alternatives include feeding breastmilk or formula with a cup, spoon, feeding syringe, or nursing supplement.

The forming of attachments is considered the foundation of the infant's capacity to form and conduct relationships throughout life. Attachment is not the same as love or affection, although they often go together. Attachments develop immediately, and a lack of attachment or a seriously disrupted attachment has the potential to cause severe damage to a child's health and well-being. Physically, one may not see symptoms or indications of a disorder, but the child may be affected emotionally. Studies show that children with secure attachments have the ability to form successful relationships, express themselves on an interpersonal basis, and have higher self-esteem.[82] Conversely children who have neglectful or emotionally unavailable caregivers can exhibit behavioral problems such as post-traumatic stress disorder or oppositional defiant disorder.[83] Oppositional-defiant disorder is a pattern of disobedient and rebellious behavior toward authority figures.

Toddlers

Toddlers are small children between 12 and 36 months old who are much more active than infants and become challenged with learning how to do simple tasks by themselves. At this stage, parents are heavily involved in showing the small child how to do things rather than just doing things for them; it is normal for the toddler to mimic the parents. Toddlers need help to build their vocabulary, increase their communication skills, and manage their emotions. Toddlers will also begin to understand social etiquette, such as being polite and taking turns.[84]

Toddlers are very curious about the world around them and are eager to explore it. They seek greater independence and responsibility and may become frustrated when things do not go the way that they want or expect. Tantrums begin at this stage, which is sometimes referred to as the 'Terrible Twos'.[85] Tantrums are often caused by the child's frustration over the particular situation, and are sometimes caused, simply because they are not able to communicate properly. Parents of toddlers are expected to help guide and teach the child, establish basic routines (such as washing hands before meals or brushing teeth before bed), and increase the child's responsibilities. It is also normal for toddlers to be frequently frustrated. It is an essential step to their development. They will learn through experience, trial, and error. This means that they need to experience being frustrated when something does not work for them in order to move on to the next stage. When the toddler is frustrated, they will often misbehave with actions like screaming, hitting or biting. Parents need to be careful when reacting to such behaviors; giving threats or punishments is usually not helpful and might only make the situation worse.[86] Research groups led by Daniel Schechter, Alytia Levendosky, and others have shown that parents with histories of maltreatment and violence exposure often have difficulty helping their toddlers and preschool-age children with the very same emotionally dysregulated behaviors which can remind traumatized parents of their adverse experiences and associated mental states.[87][88][89]

Regarding gender differences in parenting, data from the US in 2014 states that, on an average day, among adults living in households with children under age 6, women spent 1.0 hours providing physical care (such as bathing or feeding a child) to household children. By contrast, men spent 23 minutes providing physical care.[90]

Child

Younger children start to become more independent and begin to build friendships. They are able to reason and can make their own decisions in many hypothetical situations. Young children demand constant attention but gradually learn how to deal with boredom and begin to be able to play independently. They enjoy helping and also feeling useful and capable. Parents can assist their children by encouraging social interactions and modeling proper social behaviors. A large part of learning in the early years comes from being involved in activities and household duties. Parents who observe their children in play or join with them in child-driven play have the opportunity to glimpse into their children's world, learn to communicate more effectively with their children, and are given another setting to offer gentle, nurturing guidance.[91] Parents also teach their children health, hygiene, and eating habits through instruction and by example.

Parents are expected to make decisions about their child's education. Parenting styles in this area diverge greatly at this stage, with some parents they choose to become heavily involved in arranging organized activities and early learning programs. Other parents choose to let the child develop with few organized activities.

Children begin to learn responsibility and consequences for their actions with parental assistance. Some parents provide a small allowance that increases with age to help teach children the value of money and how to be responsible.

Parents who are consistent and fair with their discipline, who openly communicate and offer explanations to their children, and who do not neglect the needs of their children in any way often find they have fewer problems with their children as they mature.

When child conduct problems are encountered, behavioral and cognitive-behavioral group-based parenting interventions have been found to be effective at improving child conduct, parenting skills, and parental mental health.[92]

Adolescents

Parents often feel isolated and alone when parenting adolescents.[93] Adolescence can be a time of high risk for children, where newfound freedoms can result in decisions that drastically open up or close off life opportunities. There are also large changes that occur in the brain during adolescence; the emotional center of the brain is now fully developed, but the rational frontal cortex has not matured fully and still is not able to keep all of those emotions in check.[94] Adolescents tend to increase the amount of time spent with peers of the opposite gender; however, they still maintain the amount of time spent with those of the same gender—and do this by decreasing the amount of time spent with their parents.

Although adolescents look to peers and adults outside the family for guidance and models for how to behave, parents can remain influential in their development. Studies have shown that parents can have a significant impact, for instance, on how much teens drink.[95]

During adolescence children begin to form their identity and start to test and develop the interpersonal and occupational roles that they will assume as adults. Therefore, it is important that parents treat them as young adults. Parental issues at this stage of parenting include dealing with rebelliousness related to a greater desire to partake in risky behaviors. In order to prevent risky behaviors, it is important for the parents to build a trusting relationship with their children. This can be achieved through behavioral control, parental monitoring, consistent discipline, parental warmth and support, inductive reasoning, and strong parent-child communication.[96][97]

When a trusting relationship is built up, adolescents are more likely to approach their parents for help when faced with negative peer pressure. Helping children build a strong foundation will ultimately help them resist negative peer pressure. Not only will a positive relationship between adolescent and parent benefit when faced with peer pressure, it will help with identity-processing in early adolescents.[98] Research by Berzonsky et al. found that adolescents that were open and trusting of their parents were given more freedom and their parents were less likely to track them and control their behavior.[99]

Adults

Parenting does not usually end when a child turns 18. Support may be needed in a child's life well beyond the adolescent years and can continue into middle and later adulthood. Parenting can be a lifelong process. Parents may provide financial support to their adult children, which can also include providing an inheritance after death. The life perspective and wisdom given by a parent can benefit their adult children in their own lives. Becoming a grandparent is another milestone and has many similarities with parenting. Roles can be reversed in some ways when adult children become caregivers to their elderly parents.[98]

Assistance

Parents may receive assistance with caring for their children through child care programs.

Childbearing and happiness

Data from the British Household Panel Survey and the German Socio-Economic Panel suggests that having up to two children increases happiness in the years around the birth, and mostly only for those who have postponed childbearing. However, having a third child is not shown to increase happiness.[100]

Further reading

- Robert Levine; Sarah Levine (2017). Do Parents Matter?: Why Japanese Babies Sleep Soundly, Mexican Siblings Don't Fight & Parents Should Just Relax. Souvenir Press. ISBN 978-0285643703.

- Child custody

- Childlessness

- Developmental psychology

- Empty nest syndrome

- Family law

- LGBT parenting

- Motherhood constellation

- Outline of children

- Parent Rescue (documentary series)

- Parental alienation

- Parenting plan

- Parental supervision

- Parenting coordinator

- Paternal age effect

- Paternal care

- Pedagogy

- Shared parenting

- Sharenting

References

- Jane B. Brooks (28 September 2012). The Process of Parenting: Ninth Edition. McGraw-Hill Higher Education. ISBN 978-0-07-746918-4. For the legal definition of parenting and parenthood see: Haim Abraham, A Family Is What You Make It? Legal Recognition and Regulation of Multiple Parents (2017)

- Bernstein, Robert (20 February 2008). "Majority of Children Live With Two Biological Parents". Archived from the original on 20 April 2008. Retrieved 26 March 2009.

- Johri, Ashish (2 March 2014). "6 Steps for Parents So Your Child is Successful". humanenrich.com. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- JON., WITT (2017). SOC 2018 (5TH ed.). [S.l.]: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-1-259-70272-3. OCLC 968304061.

- Schechter, D.S., & Willheim, E. (2009). Disturbances of attachment and parental psychopathology in early childhood. Infant and Early Childhood Mental Health Issue. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Clinics of North America, 18(3), 665-87.

- Grienenberger, J., Kelly, K. & Slade, A. (2005). Maternal Reflective Functioning, Mother-Infant Affective Communication and Infant Attachment: Exploring The Link Between Mental States and Observed Caregiving. Attachment and Human Development, 7, 299-311.

- Lieberman, A.F.; Padrón, E.; Van Horn, P.; Harris, W.W. (2005). "Angels in the nursery: The intergenerational transmission of benevolent parental influences". Infant Ment. Health J. 26 (6): 504–20. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.964.1341. doi:10.1002/imhj.20071. PMID 28682485.

- Lareau, Annette (2002). "Invisible Inequality: Social Class and Child Rearing in Black Families and White Families". American Sociological Review. 67 (5): 747–76. doi:10.2307/3088916. JSTOR 3088916.

- shizuka, P. (2019). Social Class, Gender, and Contemporary Parenting Standards in the United States: Evidence from a National Survey Experiment. Social Forces, 98(1), 31–58. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/soy107

- "20th Century Evolution of American Parenting Styles". Archived from the original on 22 March 2016. Retrieved 11 May 2015..

- Weiten, W.; McCann, D. (2007). Themes and Variations. Nelson Education Ltd: Thomson Wadsworth. ISBN 978-0-17-647273-3.

- "Role of Social class in parenting". Budingstar. 7 January 2020.

- Doob, Christopher (2013) (in English). Social Inequality and Social Stratification (1st ed. ed.). Boston: Pearson. p. 165.

-

- Spera, C (2005). "A review of the relationship among parenting practices, parenting styles, and adolescent school achievement" (PDF). Educational Psychology Review. 17 (2): 125–46. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.596.237. doi:10.1007/s10648-005-3950-1. S2CID 11050947.

- Baumrind, D. (1967). Child care practices anteceding three patterns of preschool behavior. Genetic Psychology Monographs, 75, 43–88.

- Baumrind, D. (1971). Current patterns of parental authority" Developmental Psychology 4 (1, Pt. 2), 1–103.

- Baumrind, D. (1978). "Parental disciplinary patterns and social competence in children". Youth & Society. 9 (3): 238–76. doi:10.1177/0044118X7800900302. S2CID 140984313.

- McKay M (2006). Parenting Practices in Emerging Adulthood: Development of a New Measure. Thesis, Brigham Young University. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- Santrock, J.W. (2007). A topical approach to life-span development, third Ed. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Rubin, Mark (2015). "Social Class Differences in Mental Health: Do Parenting Style and Friendship Play a Role?". Mark Rubin Social Psychology Research. Archived from the original on 2 February 2016. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- Rubin, M.; Kelly, B M. (2015). "A cross-sectional investigation of parenting style and friendship as mediators of the relation between social class and mental health in a university community". International Journal for Equity in Health. 14 (87): 1–11. doi:10.1186/s12939-015-0227-2. PMC 4595251. PMID 26438013.

- Robinson, Clyde C.; Mandleco, Barbara; Olsen, Susanne Frost; Hart, Craig H. (December 1995). "Authoritative, Authoritarian, and Permissive Parenting Practices: Development of a New Measure". Psychological Reports. 77 (3): 819–830. doi:10.2466/pr0.1995.77.3.819. ISSN 0033-2941. S2CID 145062379.

- Smetana, Judith G (1 June 2017). "Current research on parenting styles, dimensions, and beliefs". Current Opinion in Psychology. Parenting. 15: 19–25. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.02.012. ISSN 2352-250X. PMID 28813261.

- Kohn, Alfie (28 March 2006). Unconditional Parenting: Moving from Rewards and Punishments to Love and Reason. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7434-8748-1.

- Lewis, Catherine C. (1981). "The effects of parental firm control: A reinterpretation of findings". Psychological Bulletin. 90 (3): 547–563. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.90.3.547. ISSN 1939-1455.

- Hedstrom, Ellen (2016). Parenting Style as a Predictor of Internal and External Behavioural Symptoms in Children: The Child's Perspective.

- Turel, Ofir; Liu, Peng; Bart, Chris (31 January 2017). "Board-Level Information Technology Governance Effects on Organizational Performance: The Roles of Strategic Alignment and Authoritarian Governance Style". Information Systems Management. 34 (2): 117–136. doi:10.1080/10580530.2017.1288523. ISSN 1058-0530. S2CID 39501061.

- Joseph M. V., John J. (2008). Global Academic Society Journal: Social Science Insight, Vol. 1, No. 5, pp. 16-25. ISSN 2029-0365 "Impact of Parenting Styles on Child Development".

- Armstrong, Kathleen Hague; Ogg, Julia A.; Sundman-Wheat, Ashley N.; Walsh, Audra St. John (20 May 2013), "Early Childhood Development Theories", Evidence-Based Interventions for Children with Challenging Behavior, New York, NY: Springer New York, pp. 21–30, doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-7807-2_2, ISBN 978-1-4614-7806-5, retrieved 27 March 2022

- Grolnick, Wendy S. (2012). "The Relations among Parental Power Assertion, Control, and Structure: Commentary on Baumrind". Human Development. 55 (2): 57–64. doi:10.1159/000338533. ISSN 0018-716X. JSTOR 26764606. S2CID 144535005.

- Fletcher, A. C.; Walls, J.K.; Cook, E.C.; Madison, K.J.; Bridges, T.H. (December 2008). "Parenting Style as a Moderator of Associations Between Maternal Disciplinary Strategies and Child Well-Being" (PDF). Journal of Family Issues. 29 (12): 1724–44. doi:10.1177/0192513X08322933. S2CID 38460545.

- Fletcher, A. C.; Walls, J.K.; Cook, E.C.; Madison, K.J.; Bridges, T.H. (December 2008). "Parenting Style as a Moderator of Associations Between Maternal Disciplinary Strategies and Child Well-Being" (PDF). Journal of Family Issues. 29 (12): 1724–44. doi:10.1177/0192513X08322933. S2CID 38460545.

- Friedson, Michael (1 January 2016). "Authoritarian parenting attitudes and social origin: The multigenerational relationship of socioeconomic position to childrearing values". Child Abuse & Neglect. 51: 263–275. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.10.001. ISSN 0145-2134. PMID 26585215.

- Famlii (2 February 2015). "Parenting Styles and Wealth: Concerted Cultivation by Annette Lareau". Famlii. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- Zahedani ZZ; Rezaee R; Yazdani Z; Bagheri S; Nabeiei P (2016). "The Influence of Parenting Style on Academic Achievement and Career Path". Journal of Advances in Medical Education & Professionalism. 4 (3): 130–134. PMC 4927255. PMID 27382580.

- Lassonde, Stephen (2017). "Authority, disciplinary intimacy & parenting in middle-class America". European Journal of Developmental Psychology. 14 (6): 714–732. doi:10.1080/17405629.2017.1300577. S2CID 151783083.

- "permissive parenting". MSU.EDU.

- Brown, Lola; Iyengar, Shrinidhi (2008). "Parenting Styles: The Impact on Student Achievement". Marriage & Family Review. 43 (1–2): 14–38. doi:10.1080/01494920802010140. S2CID 144129154.

- Zelizer, Viviana A. (28 August 1994). Pricing the Priceless Child: The Changing Social Value of Children. Princeton University Press. pp. 57+. ISBN 978-0-691-03459-1.

- Finkelhor, D.; Ormrod, R.; Turner, H.; Holt, M. (November 2009). "Pathways to Poly-Victimization" (PDF). Child Maltreatment. 14 (4): 316–29. doi:10.1177/1077559509347012. PMID 19837972. S2CID 14676857.

- Finkelhor, D.; Ormrod, R.; Turner, H.; Holt, M. (November 2009). "Pathways to Poly-Victimization" (PDF). Child Maltreatment. 14 (4): 316–29. doi:10.1177/1077559509347012. PMID 19837972. S2CID 14676857.

- Weymouth, Bridget B.; Buehler, Cheryl (7 September 2015). "Adolescent and Parental Contributions to Parent–Adolescent Hostility Across Early Adolescence". Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 45 (4): 713–729. doi:10.1007/s10964-015-0348-3. PMC 4781678. PMID 26346035.

- Butts, Renee (2022). Psychological Manipulation. Salem Press Encyclopedia.

- Romm, Katelyn F.; Metzger, Aaron; Alvis, Lauren M. (2020). "Parental Psychological Control and Adolescent Problematic Outcomes: A Multidimensional Approach". Journal of Child & Family Studies. 29: 195–207. doi:10.1007/s10826-019-01545-y. S2CID 203447544 – via OneSearch.

- Gray, Peter (5 March 2013). Free to Learn: Why Unleashing the Instinct to Play Will Make Our Children Happier, More Self-Reliant, and Better Students for Life. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-03791-9.

- Gray, Peter (2009). "Why Have Trustful Parenting & Children's Freedom Declined? | Psychology Today". Psychology Today. Retrieved 24 March 2023.

- Kuppens, Sofie; Ceulemans, Eva (18 September 2018). "Parenting Styles: A Closer Look at a Well-Known Concept". Journal of Child and Family Studies. 28 (1): 168–181. doi:10.1007/s10826-018-1242-x. ISSN 1062-1024. PMC 6323136. PMID 30679898.

- Bolin, Inge (2006). Growing Up in a Culture of Respect: Child Rearing in Highland Peru. University of Texas Press. pp. 63–67. ISBN 978-0-292-71298-0.

- Neha, Tia; Reese, Elaine; Schaughency, Elizabeth; Taumoepeau, Mele (August 2020). "The role of whānau (New Zealand Māori families) for Māori children's early learning". Developmental Psychology. 56 (8): 1518–1531. doi:10.1037/dev0000835. ISSN 1939-0599. PMID 32790450. S2CID 221124818.

- Day, Nicholas (30 April 2013). "Cultural differences in how you look and talk at your baby". Slate. Retrieved 3 May 2013.

- Olcer, Sevinc; Aytar, Abide Gungor (25 August 2014). "A Comparative Study into Social Skills of Five-six Year Old Children and Parental Behaviors". Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences. 141: 976–995. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.05.167.

- Maccoby, Eleanor E. (1994), "The role of parents in the socialization of children: An historical overview.", A century of developmental psychology, Washington: American Psychological Association, pp. 589–615, doi:10.1037/10155-021, ISBN 1-55798-233-3, retrieved 27 March 2022

- Schuck, Rachel K.; Lambert, Rachel (5 November 2020). ""Am I Doing Enough?" Special Educators' Experiences with Emergency Remote Teaching in Spring 2020". Education Sciences. MDPI. 10 (11): 320. doi:10.3390/educsci10110320. ISSN 2227-7102.

- Patterson et al. (1992)

-

- Chase-Lansdale, P.L.; Cherlin, A.J.; Kiernan, K.E. (1995). "The Long-Term Effects of Parental Divorce on the Mental Health of Young Adults: A Developmental Perspective". Child Development. 66 (6): 1614–1634. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00955.x. PMID 8556889.

- Hetherington, 1992

- Zill, N., Morrison, D. R., & Coiro, M. J. (1993). Long-term effects of parental divorce on parent-child relationships, adjustment, and achievement in young adulthood. Journal of Family Psychology, 7(1), 91–103. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.7.1.91

- Bumpass, L., Sweet, J., & Martin, T. C. (1990). Changing Patterns of Remarriage. Journal of Marriage and Family, 52(3), 747–756. doi:10.2307/352939 JSTOR 352939

- Hetherington, E. M., Bridges, M., & Insabella, G. M. (1998). What matters? What does not? Five perspectives on the association between marital transitions and children's adjustment. American Psychologist, 53(2), 167–184. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.53.2.167

- Sanders, Matthew R. (2008). "Triple P-Positive Parenting Program as a public health approach to strengthening parenting". Journal of Family Psychology. 22 (4): 506–17. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1012.8778. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.22.3.506. PMID 18729665. S2CID 23720716.

- Common Sense Parenting, Burke, 1997, p. 83

- Better Home Discipline, Cutts, 1952, p. 7

- "Choosing a Parent Training Program". Child Mind Institute. Retrieved 7 July 2022.

- Barlow, Jane; Smailagic, Nadja; Huband, Nick; Roloff, Verena; Bennett, Cathy (17 May 2014). "Group-based parent training programmes for improving parental psychosocial health" (PDF). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (5): CD002020. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002020.pub4. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 24838729.

- Day, Nicholas (10 April 2013). "Parental ethnotheories and how parents in America differ from parents everywhere else". Slate. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

- Day, Nicholas (9 April 2013). "Give Your Baby a Machete and Other #BabySlatePitches". Slate. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

- Robert K. Thomas. 1958. "Cherokee Values and World View" Unpublished MS, University of North Carolina Available at: http://works.bepress.com/robert_thomas/40 Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Doan, Stacey N. (May 2017). "Consequences of 'Tiger' Parenting: A Cross-Cultural Study of Maternal Psychological Control and Children's Cortisol Stress Response". Developmental Science. 20 (3): 10. doi:10.1111/desc.12404. hdl:2027.42/136743. PMID 27146549.

- Archibald, Jo-Ann, (2008). Indigenous Storywork: Educating The Heart, Mind, Body and Spirit. Vancouver, British Columbia: The University of British Columbia Press.

- Delgado-Gaitan, Concha (1994). "Consejos: The Power of Cultural Narratives". Anthropology & Education Quarterly. 25 (3): 298–316. doi:10.1525/aeq.1994.25.3.04x0146p. JSTOR 3195848.

- Brown, P. (2002). Everyone has to lie in Tzeltal. (pp. 241–75) Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, Mahwah, NJ.

- Source: Chisholm, J.S. (1996). Learning "respect for everything": Navajo images of development. Images of childhood, 167–183.

- Paradise, Ruth; Rogoff, Barbara. "Side by Side: Learning by Observing and Pitching In". Journal of the Society of Psychological Anthropology: 102–37.

- Gaskins, Suzanne; Paradise, Ruth (2010). "Learning Through Observation in Daily Life". In Lancy, David; Bock, John; Gaskins, Suzanne (eds.). The Anthropology of Learning in Childhood. United Kingdom: AltaMira Press.

- Wang, Ming-Te; Henry, Daphne A.; Smith, Leann V.; Huguley, James P.; Guo, Jiesi (January 2020). "Parental ethnic-racial socialization practices and children of color's psychosocial and behavioral adjustment: A systematic review and meta-analysis". American Psychologist. 75 (1): 1–22. doi:10.1037/amp0000464. ISSN 1935-990X. PMID 31058521. S2CID 145820076.

- Lee, Richard M.; Grotevant, Harold D.; Hellerstedt, Wendy L.; Gunnar, Megan R. (December 2006). "Cultural socialization in families with internationally adopted children". Journal of Family Psychology. 20 (4): 571–580. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.20.4.571. ISSN 1939-1293. PMC 2398726. PMID 17176191.

- McHale, Susan M.; Crouter, Ann C.; Kim, Ji-Yeon; Burton, Linda M.; Davis, Kelly D.; Dotterer, Aryn M.; Swanson, Dena P. (September 2006). "Mothers' and Fathers' Racial Socialization in African American Families: Implications for Youth". Child Development. 77 (5): 1387–1402. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00942.x. hdl:2027.42/97223. ISSN 0009-3920. PMID 16999806.

- Bannon, William M.; McKay, Mary M.; Chacko, Anil; Rodriguez, James A.; Cavaleri, Mary (January 2009). "Cultural Pride Reinforcement as a Dimension of Racial Socialization Protective of Urban African American Child Anxiety". Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services. 90 (1): 79–86. doi:10.1606/1044-3894.3848. ISSN 1044-3894. PMC 2749692. PMID 20046919.

- Huguley, James P.; Wang, Ming-Te; Vasquez, Ariana C.; Guo, Jiesi (May 2019). "Parental ethnic–racial socialization practices and the construction of children of color's ethnic–racial identity: A research synthesis and meta-analysis" (PDF). Psychological Bulletin. 145 (5): 437–458. doi:10.1037/bul0000187. ISSN 1939-1455. PMID 30896188. S2CID 84845230.

- Priest, Naomi; Walton, Jessica; White, Fiona; Kowal, Emma; Baker, Alison; Paradies, Yin (November 2014). "Understanding the complexities of ethnic-racial socialization processes for both minority and majority groups: A 30-year systematic review". International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 43: 139–155. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2014.08.003. ISSN 0147-1767.

- Yasui, Miwa (September 2015). "A review of the empirical assessment of processes in ethnic–racial socialization: Examining methodological advances and future areas of development". Developmental Review. 37: 1–40. doi:10.1016/j.dr.2015.03.001. ISSN 0273-2297.

- Sedgh, Gilda; Singh, Susheela; Hussain, Rubina (10 September 2014). "Intended and Unintended Pregnancies Worldwide in 2012 and Recent Trends". Studies in Family Planning. 45 (3): 301–14. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4465.2014.00393.x. ISSN 0039-3665. PMC 4727534. PMID 25207494.

- Dean, Sohni V.; Lassi, Zohra S.; Imam, Ayesha M.; Bhutta, Zulfiqar A. (26 September 2014). "Preconception care: nutritional risks and interventions". Reproductive Health. 11 (Suppl 3): S3. doi:10.1186/1742-4755-11-S3-S3. PMC 4196560. PMID 25415364.

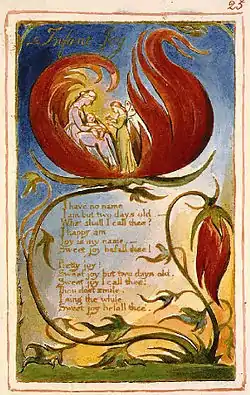

- Morris Eaves; Robert N. Essick; Joseph Viscomi (eds.). "Songs of Innocence and of Experience, copy AA, object 25 (Bentley 25, Erdman 25, Keynes 25) "Infant Joy"". William Blake Archive. Archived from the original on 17 January 2014. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- Gartner LM; Morton J; Lawrence RA; Naylor AJ; O'Hare D; Schanler RJ; Eidelman AI; et al. (February 2005). "Breastfeeding and the Use of Human Milk". Pediatrics. 115 (2): 496–506. doi:10.1542/peds.2004-2491. PMID 15687461.

- van der Voort, Anja; Juffer, Femmie; J. Bakermans-Kranenburg, Marian (1 January 2014). Barlow, Jane (ed.). "Sensitive parenting is the foundation for secure attachment relationships and positive social-emotional development of children". Journal of Children's Services. 9 (2): 165–176. doi:10.1108/JCS-12-2013-0038. ISSN 1746-6660.

- SS, Hamilton. "Result Filters." National Center for Biotechnology Information. U.S. National Library of Medicine, 1 October 2008. Web. 13 March 2013.

- Fox, Isadora (11 June 2015). "Teaching Kids to Mind Their Manners: How to Raise a Polite Child". Parents.

- "The Terrible Twos Explained – Safe Kids (UK)". Safe Kids. 10 May 2011. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- Pitman, Teresa. "Toddler Frustration". Todaysparent. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- Schechter, Daniel S.; Willheim, Erica; Hinojosa, Claudia; Scholfield-Kleinman, Kimberly; Turner, J. Blake; McCaw, Jaime; Zeanah, Charles H.; Myers, Michael M. (2010). "Subjective and Objective Measures of Parent-Child Relationship Dysfunction, Child Separation Distress, and Joint Attention". Psychiatry. 73 (2): 130–44. doi:10.1521/psyc.2010.73.2.130. PMID 20557225. S2CID 5132495.

- Schechter, Daniel S.; Zygmunt, Annette; Coates, Susan W.; Davies, Mark; Trabka, Kimberly A.; McCaw, Jaime; Kolodji, Ann; Robinson, Joann L. (2007). "Caregiver traumatization adversely impacts young children's mental representations on the MacArthur Story Stem Battery". Attachment & Human Development. 9 (3): 187–205. doi:10.1080/14616730701453762. PMC 2078523. PMID 18007959.

- Levendosky, Alytia A.; Leahy, Kerry L.; Bogat, G. Anne; Davidson, William S.; von Eye, Alexander (2006). "Domestic violence, maternal parenting, maternal mental health, and infant externalizing behavior". Journal of Family Psychology. 20 (4): 544–52. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.20.4.544. PMID 17176188.

- "American Time Use Survey". Bureau of Labor Statistics. 24 June 2015.

- Kenneth R. Ginsburg. "The Importance of Play in Promoting Healthy Child Development and Maintaining Strong Parent-Child Bonds" (PDF). American Academy of Pediatrics. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 October 2009.

- Furlong, M; McGilloway, S; Bywater, T; Hutchings, J; Smith, SM; Donnelly, M (15 February 2012). "Behavioural and Cognitive-Behavioural Group-Based Parenting Programmes for Early-Onset Conduct Problems in Children Aged 3 to 12 Years". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD008225. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008225.pub2. PMID 22336837.

- Sharenting – Now became Oversharenting & Danger Archived 16 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- "What was my teenager thinking?". Talking to Teens. 26 September 2017. Retrieved 12 February 2018.

- "7 Things Most Parents Get Wrong About Teen Drinking". Talking to Teens. 7 July 2017. Retrieved 12 February 2018.

- Hoskins, Donna (18 September 2014). "Consequences of Parenting on Adolescent Outcomes". Societies. 4 (3): 506–531. doi:10.3390/soc4030506. ISSN 2075-4698.

- Newman, Kathy; Harrison, Lynda; Dashiff, Carol; Davies, Susan (February 2008). "Relationships between parenting styles and risk behaviors in adolescent health: an integrative literature review". Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem. 16 (1): 142–150. doi:10.1590/S0104-11692008000100022. ISSN 0104-1169. PMID 18392544.

- Dellmann-Jenkins, Mary; Blankemeyer, Maureen; Pinkard, Odessa (April 2000). "Young Adult Children and Grandchildren in Primary Caregiver Roles to Older Relatives and Their Service Needs". Family Relations. 49 (2): 177–186. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3729.2000.00177.x. ISSN 0197-6664.

- Berzonsky, Michael D., Susan JT Branje, and Wim Meeus. "Identity-processing style, psychosocial resources, and adolescents' perceptions of parent-adolescent relations." The Journal of Early Adolescence 27.3 (2007): 324-345.

- Mikko Myrskylä; Rachel Margolis (2014). "Happiness: Before and After the Kids". Demography. 51 (5): 1843–66. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.454.2051. doi:10.1007/s13524-014-0321-x. PMID 25143019. S2CID 8127506.