Multilingual inscription

In epigraphy, a multilingual inscription is an inscription that includes the same text in two or more languages. A bilingual is an inscription that includes the same text in two languages (or trilingual in the case of three languages, etc.). Multilingual inscriptions are important for the decipherment of ancient writing systems, and for the study of ancient languages with small or repetitive corpora.

Examples

Bilinguals

Important bilinguals include:

- the first known Sumerian-Akkadian bilingual tablet dating to the reign of Rimush, circa 2270 BCE.[1][2]

- the Urra=hubullu tablets (c. 2nd millennium BCE; Babylon) in Sumerian and Akkadian; one tablet is a Sumerian-Hurrian bilingual glossary.

- the bilingual Ebla tablets (2500–2250 BCE; Syria) in Sumerian and Eblaite

- the bilingual Ugarit Inscriptions (1400–1186 BCE; Syria):[3]

- tablets in Akkadian and Hittite

- tablets in Akkadian and Hieroglyphic Luwian

- tablets in Sumerian and Akkadian

- tablets in Ugaritic and Akkadian

- the Karatepe Bilingual (8th century BCE; Osmaniye Province, Turkey) in Phoenician and Hieroglyphic Luwian

- the Tell el Fakhariya Bilingual Inscription (9th century BCE; Al-Hasakah Governorate, Syria) in Aramaic and Akkadian

- the Çineköy inscription (8th century BCE; Adana Province, Turkey) in Hieroglyphic Luwian and Phoenician

- the Assyrian lion weights (8th century BCE; Nimrud, Iraq) in Akkadian (Assyrian dialect, using cuneiform script) and Aramaic (using Phoenician script)

- the Kandahar Edict of Ashoka (3rd century BCE; Afghanistan) in Ancient Greek and Aramaic

- the Amathus Bilingual (600 BCE; Cyprus) in Eteocypriot and Ancient Greek (Attic dialect)

- the Idalion bilingual inscription that helped to decipher the Cypro-Syllabic script

- the Pyrgi Tablets (500 BCE; Lazio, Italy) in Etruscan and Phoenician

- the Kaunos Bilingual (330–300 BCE; Turkey), in Carian and Ancient Greek

- the Philae obelisk (118 BCE; Egypt), in Egyptian hieroglyphs and Ancient Greek

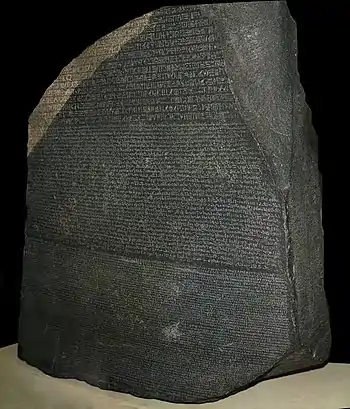

- the Rosetta Stone Series, in Egyptian (using Hieroglyphic and Demotic scripts) and Ancient Greek; they allowed the decipherment of Egyptian hieroglyphs (especially the last one)

- the Raphia Decree (217 BCE; Memphis, Egypt)

- the Decree of Canopus (238–237 BCE; Tanis, Egypt)

- the Rosetta Stone decree (196 BCE; Egypt): the Rosetta Stone and the Nubayrah Stele

- the Cippi of Melqart (2nd century BCE; Malta) in Phoenician and Ancient Greek; discovered in Malta in 1694, the key which allowed French scholar Abbé Barthelemy to decipher the Phoenician script

- the Punic-Libyan Inscription (146 BCE; Dougga, Tunisia) in Libyan and Punic; from the Mausoleum of Ateban, now held at the British Museum, it allowed the decipherment of Libyan

- the Monumentum Ancyranum inscription (14 CE; Ankara, Turkey) in Latin and Greek; it reproduces and translates the Latin inscription of the Res Gestae Divi Augusti

- the Stele of Serapit (150 CE; Kartli, Tbilisi) in Ancient Greek and Armazic (a local variant of Aramaic)

- the Velvikudi inscription (8th century; India) in Sanskrit and Tamil

- the Valun tablet (11th century; Cres, Croatia) in Old Croatian (using Glagolitic script) and Latin

- the Muchundi Inscription (13th century; Kozhikode, India) in Arabic and Malayalam

- the Kalyani Inscriptions (1479; Bago, Burma) in Mon and Pali (using Burmese script)

The manuscript titled Relación de las cosas de Yucatán (1566; Spain) shows the de Landa alphabet (and a bilingual list of words and phrases), written in Spanish and Mayan; it allowed the decipherment of the Pre-Columbian Maya script in the mid-20th century.

Trilinguals

Important trilinguals include:

- the trilingual Aphek-Antipatris inscription (1550–1200 BCE; Tell Aphek, Israel) in Sumerian, Akkadian and Canaanite; it is a lexicon

- the trilingual Ugarit Inscriptions (1400–1186 BCE; Syria):

- the Achaemenid royal inscriptions in Old Persian, Elamite and Akkadian (Babylonian dialect); it allowed the decipherment of cuneiform script

- the Xanthos Obelisk (500 BCE; Xanthos, Turkey) in Ancient Greek, Lycian and Milyan

- the Van Fortress inscription (5th century BCE; Van, Turkey) in Old Persian, Akkadian (Babylonian dialect), and Elamite; it allowed the decipherment of Old Persian.

- the Letoon trilingual (358–336 BCE; Turkey), in standard Lycian or Lycian A, Ancient Greek and Aramaic

- the Ezana Stone (356 CE; Aksum, Ethiopia) in Ge'ez, Sabaean and Ancient Greek

- the Monumentum Adulitanum (3rd century CE; Adulis, Eritrea) in Ge'ez, Sabaean and Ancient Greek

- the trilingual epitaph for Meliosa (5th–6th century; Tortosa, Spain) in Hebrew, Latin and Greek; the Jewish headstone includes a pentagram and a five-branched menorah in the Latin text.[4]

- the Galle Trilingual Inscription (1409; Southern Province, Sri Lanka) in Chinese, Tamil and Persian

- the Yongning Temple Stele (1413; Tyr, Russia) in Chinese, Mongolian and Jurchen; see below.

- the Shwezigon Pagoda Bell Inscription (1557; Bagan, Burma) in Burmese, Mon and Pali

Quadrilinguals

Important quadrilinguals include:

- the quadrilingual Ugarit Inscription (c. 14th century BC; Syria) in Sumerian, Akkadian, Hurrian and Ugaritic.[3]

- the Myazedi inscription (1113; Bagan, Burma) in Burmese, Pyu, Mon and Pali; it allowed the decipherment of Pyu.

- the Yongning Temple Stele (1413, Tyr, Russia) in Chinese (using Traditional characters), Jurchen, Mongolian (using Mongolian script) and Classical Tibetan; the Buddhist mantra Om mani padme hum is transcribed from Sanskrit using 4 scripts arranged vertically on sides, and there is another Chinese text engraved on the front with abbreviated Mongolian & Jurchen translations on the back.

Inscriptions in five or more languages

Important examples in five or more languages include:

- the Sawlumin inscription (1053–1080; Myittha Township, Burma) in Burmese, Pyu, Mon, Pali and Sanskrit (or Tai-Yuan, Gon (Khun or Kengtung) Shan; in Devanagari script)

- the Cloud Platform at Juyong Pass inscriptions (1342–1345; Beijing, China) in Sanskrit (using the Tibetan variant of Ranjana script called Lanydza), Classical Tibetan, Mongolian (using 'Phags-pa script), Old Uyghur (using Old Uyghur script), Chinese (using Traditional characters) and Tangut; it engraves two different Buddhist dharani-sutras transcriptions from Sanskrit using 6 scripts, another text ("Record of Merits in the Construction of the Pagoda") in 5 languages (without Sanskrit version), and a Chinese & Tangut summary of one dharani-sutra.

- the Stele of Sulaiman (1348; Gansu, China) in Sanskrit, Classical Tibetan, Mongolian, Old Uyghur, Chinese and Tangut (like the inscriptions at Juyong Pass); the Buddhist mantra Om mani padme hum is transcribed from Sanskrit using 6 scripts (last 4 arranged vertically), below another Chinese engraving.

Modern examples

Notable modern examples include:

- the cornerstone of the UN headquarters (1949; New York, USA) in English, French, Chinese (using Traditional characters), Russian and Spanish; the text "United Nations" in each official language and "MCMXLIX" (the year in Roman numerals) are etched on stone.[5]

- Peace poles (since 1955; around the world), displaying each one the message "May Peace Prevail on Earth" in multiple languages (4–16 each one)

- the Georgia Guidestones (1980, Elbert County, Georgia, USA), with two multilingual inscriptions

- a short message at the top in four ancient languages, i.e., in Akkadian (Babylonian dialect; using cuneiform script), Ancient Greek, Sanskrit (using Devanagari script) and Egyptian (using Hieroglyphic script)

- the ten guidelines on the slabs in eight modern languages, i.e., in English, Spanish, Swahili (using Latin script), Hindi (using Devanagari script), Hebrew, Arabic, Chinese (using Traditional characters) and Russian (using Cyrillic script).

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948; Paris, France) was originally written in English and French. In 2009, it became the most translated document in the world (370 languages and dialects).[6] Unicode stores 481 translations as of November 2021.[7]

See also

References

- Thureau-Dangin, F. (1911). "Notes assyriologiques" [Assyriological notes]. Revue d'Assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale (in French). 8 (3): 138–141. JSTOR 23284567.

- "tablette". Louvre Collections. Retrieved 2021-11-01.

- Meyers, Eric M., ed. (1997). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Archaeology in the Near East. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Noy, David (1993). Jewish Inscriptions of Western Europe. Vol. 1: Italy (Excluding the City of Rome), Spain and Gaul. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 247–249.

- "Where is the Cornerstone of the UN Headquarters in New York?". Dag Hammarskjöld Library. Retrieved 2021-11-01.

- "Most Translated Document". Guinness World Records. Retrieved 2021-11-01.

- "Translations". UDHR In Unicode. Retrieved 2021-11-01.

External links

Media related to Multilingual inscriptions at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Multilingual inscriptions at Wikimedia Commons