Cue stick

A cue stick (or simply cue, more specifically billiards cue, pool cue, or snooker cue) is an item of sporting equipment essential to the games of pool, snooker and carom billiards. It is used to strike a ball, usually the cue ball. Cues are tapered sticks, typically about 57–59 inches (about 1.5 m) long and usually between 16 and 21 ounces (450–600 g), with professionals gravitating toward a 19-ounce (540 g) average. Cues for carom tend toward the shorter range, though cue length is primarily a factor of player height and arm length. Most cues are made of wood, but occasionally the wood is covered or bonded with other materials including graphite, carbon fiber or fiberglass. An obsolete term for a cue, used from the 16th to early 19th centuries, is billiard stick.[3][4]

History

The forerunner of the cue was the mace, an implement similar to a light-weight golf club, with a foot that was generally used to shove rather than strike the cue ball.[3] When the ball was frozen against a rail cushion, use of the mace was difficult (the foot would not fit under the edge of the cushion to strike the ball squarely), and by 1670 experienced players often used the tail or butt end of the mace instead.[3] The term "cue" comes from queue, the French word for "tail", in reference to this practice,[3] a style of shooting that eventually led to the development of separate, footless cue sticks by about 1800, used initially as adjuncts to the mace,[3] which remained in use until well into the 19th century.[5] In public billiard rooms only skilled players were allowed to use the cue, because the fragile cloth could be torn by novices.[3] The introduction of the cue, and the new game possibilities it engendered, led to the development of cushions with more rebound, initially stuffed with linen or cotton flocking, but eventually replaced by rubber.[3]

The idea of the cue initially was to try to strike the cue-ball as centrally as possible to avoid a miscue.[3] The concept of spin on the cue ball was discovered before cue-tips had been invented; e.g. striking the bottom of the cue ball to make it go backwards upon contact with an object ball.[3] François Mingaud was studying the game of billiards while being held in Paris as a political prisoner, and experimented with a leather cue tip. In 1807, he was released and demonstrated his invention.[3] Mingaud is also credited with the discovery that by raising the cue vertically, to the position adopted by the mace, he could perform what is now known as a massé shot.[3]

In pre-tip days, it was common for players to twist the ends of their cue into a plaster wall or ceiling so that a chalk-like deposit would form on the end to reduce the chance of a miscue, thus giving rise to the modern billiard chalk.[3] The first systematic marketing of chalk was by John Carr, a marker in John Bartley's billiard rooms in Bath. Between Carr and Bartley, it was discovered how "side" (sidespin) could be used to the advantage of players, and Carr began selling chalk in small boxes. He called it "twisting powder", and the magical impression this gave the public enabled him to sell it for a higher price than if they realized it was simply chalk in a small box.[3] "English", an American term for sidespin, derives from the British discovery of sidespin's effects, as "massé" comes from the French word for "mace".[3]

Types

Pool and snooker cues average around 57–59 inches (140–150 cm) in length and are of three major types. The simplest type is a one-piece cue; these are generally stocked in pool halls for communal use. They have a uniform taper, meaning they decrease in diameter evenly from the end or butt to the tip. A second type is the two-piece cue, divided in the middle for ease of transport, usually in a cue case or pouch. A third variety is another two-piece cue, but with a joint located three-quarters down the cue (usually 12 or 16 inches away from the butt), known as a "three-quarter two-piece", used by snooker players.

Pool

A typical two piece cue for pocket billiards is usually made mostly of hard or rock maple, with a fiberglass or phenolic resin ferrule, usually 0.75 to 1 inch (19 to 25 mm) long, and steel joint collars and pin. Pool cues average around 59 inches (150 cm) long, are commonly available in 17–21 ounces (0.48–0.60 kg) weights, with 19 ounces (0.54 kg) being the most common, and usually have a tip diameter in the range of 12 to 14 mm.[6] A conical taper, with the shaft gradually shrinking in diameter from joint to ferrule, is favored by some, but the "pro" taper is increasingly popular, straight for most of the length of the shaft from ferrule back, flaring to joint diameter only in the last 1⁄4 to 1⁄3 of the shaft. While there are many custom cuemakers, a very large number of quality pool cues are manufactured in bulk. In recent years, modern materials such as fiberglass, carbon fiber, aluminum, etc., have been used more and more for shafts and butts. A trend toward experimentation has also developed with rubber, memory foam and other soft wraps.

Carom

Carom billiards cues tend to be shorter and lighter than pool cues, with a shorter ferrule, a thicker butt and joint, a wooden joint pin (ideally) and collarless wood-to-wood joint, a conical taper, and a smaller tip diameter. Typical dimensions are 54–56 inches (140–140 cm) long, 16.5–18.5 ounces (0.47–0.52 kg) in weight, with an 11–12 mm diameter tip.[6] The specialization makes the cue stiffer, for handling the heavier billiard balls and acting to reduce deflection.[1]: 79, 241 The wood used in carom cues can vary widely, and most quality carom cues are handmade.

Snooker

At 57–58 inches (140–150 cm), a cue designed for snooker is usually shorter than the typical 59 inch pool cue and has detachable butt extensions for making the cue 6 inches (15 cm) longer or more.[7] Many snooker cues are jointed, usually with brass fittings, 2⁄3 or even 3⁄4 of the way back toward the butt bumper, providing an unusually long shaft, rather than at the half-way point, where pool and carom cues are jointed. This necessitates an extra long cue case. Some models are jointed in two places, with the long shaft having a smooth and subtle wood-to-wood joint. Snooker cue tips are usually 8.5 – 10.5 mm in diameter to provide more accuracy and finesse with snooker balls, which are smaller than pool and carom varieties. Snooker butts are usually flat on one side so that the cue may be laid flat on the table bed and slid along the baize under a cushion to strike the cushion-ward side of the cue ball when it is frozen to the cushion (such a shot is not legal in pool or carom games under most rulesets). This tactile flat part of the butt also helps the player develop a very specific way of holding the cue, consistent on every shot for a very uniform stroke (snooker, in the case of many if not most shots, requires much more precision than pool). Snooker cue weights vary between 16 and 18 oz. While a lighter cue is usually for beginners to develop correct technique when starting out, some professional snooker players use lighter cues (15 – 16 1/2 oz.), Joe Davis, John Spencer, Terry Griffiths, Mark Williams and Paul Hunter, to name a few. The balance point of a cue is usually 16 to 18 inches from the butt end.

Minimum length for a snooker cue

The official rules of both snooker and billiards state that "A cue shall be not less than 3 ft (914 mm) in length and shall show no change from the traditional tapered shape and form, with a tip, used to strike the cue-ball, secured to the thinner end."[8] This rule was introduced following an incident on 14 November 1938 when Alec Brown was playing Tom Newman at Thurston's Hall in the 1938/1939 Daily Mail Gold Cup. In the third frame, Brown potted a red, after which the cue ball was left amidst several reds, with only a narrow way through to the black, the only colour not snookered, and which was near its spot. Playing this with conventional equipment would have been awkward. To the surprise of spectators, Brown produced a small fountain pen-sized cue from his vest pocket, chalked it, and played the stroke. Newman protested at this.

The referee, Charles Chambers, then inspected the implement, a strip of ebony about five inches long, with one end having a cue tip. Chambers decided to award a foul, and awarded Newman seven points. In response to questions, the referee quoted the rule that said all strokes must be made with the tip of the cue, so he did not regard the "fountain-pen cue" as a valid cue. Eight days later, the Billiards Association and Control Council, which owned the rules, met and decided to introduce a new rule, which has been developed into today's version: "A billiards cue, as recognised by the Billiards and Control Council, shall not be less than three feet in length, and shall show no substantial departure from the traditional and generally accepted shape and form."[9][10]

Speciality

Manufacturers also provide a variety of specialty cues tailored to specific shots. Pool break cues have tips made from very hard leather (sometimes layered) or phenolic resin to ensure that the full force of the stroke is transferred to the cue ball during the break shot, and to avoid excessive wear-and-tear on the tips and ferrules of players' main shooting cues. Phenolic-tipped break cues often have a merged phenolic ferrule-tip, instead of two separate pieces.

Jump cues are shorter, lighter (12 ounces and less) cues that make performing a legal jump shot easier, and also often have a very hard tip. Some standard-sized break cues include a two-piece butt allowing a player to remove the lower, heavier half of the butt to produce a jump cue; these are usually referred to as jump–break or break–jump cues. The uncommon massé cue is short and heavy, with a wider tip to aid in making massé shots.

Practitioners of artistic billiards and artistic pool sometimes have twenty or more cues, each specifically tailored to a particular trick shot. Other specialty cues have multiple sections, between which weights can be added. Another specialization is the butt extension, which can be slipped over or screwed into the normal butt, to lengthen the cue and reduce dependency on the mechanical bridge.

A high quality two-piece cue with a nearly invisible wood-to-wood joint, so that it looks like a cheap one-piece house cue, is called a sneaky pete.[11] Such a cue may be used by a hustler to temporarily fool unsuspecting gamblers into thinking that he or she is a novice.

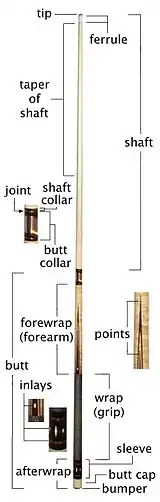

Shaft

Shafts are made with various tapers, the two most common being the pro taper and the European taper. The pro taper has the same diameter from the tip to 30–35 cm (12–14 inches) toward the joint, at which point it begins to widen. The European taper widens continually and smoothly from the ferrule toward the joint. Despite their names, the continually sloping European taper is found in most North American bar and house cues, and not all professional players prefer a straight pro taper on their custom, two-piece models.

Tip

Leather tips of varying curvature and degrees of hardness are glued to (or in some cases screwed into) the ferrule. The de facto standard curvatures for a pool tip are dime- and nickel-radius, determined by shaping a tip so that when one puts a nickel or dime to it, they have the same curvature. The tip end of the cue varies in diameter but is typically in the 9 to 14 millimeter range with 12 to 13 mm for pool cues. Snooker cue tips vary from 8 to 11 mm with 9 to 10 mm being the most popular size.

Rounder (i.e., smaller radius) tips impart spin to the cue ball more easily since the point of contact between the tip and the ball requires less distance from the center hit to impart the same amount of spin, due to the increased tangential contact. Tips for break and jump cues are usually nickel radius or even flatter, and sometimes made of harder materials such as phenolic resin; the shots are forceful, and usually require less spin.

A leather tip naturally compresses and hardens with subsequent shots. Without proper care, the surface of the tip can develop an undesired smoothness or glossiness which can significantly reduce the desired friction between the tip and the cue ball. Cue chalk is applied to the tip of the cue, ideally after every other shot or so, to help achieve the desired friction and minimize the chance of a miscue. This is especially important when the cue tip does not hit the cue ball in its center and thereby imparts spin to the cue ball.

There are different grades of hardness for tips, ranging from very soft to very hard. Softer tips (major brands include Elk Master and Blue Diamond) hold chalk better, but tend to degrade faster from abrasion (from chalk and scuffers), shaping (from cue tip shapers/tackers/picks), and mushrooming (the sides of the tip bulge out from long normal use or from hard hits that compact the tip in all directions). Harder tips (major brands include Blue Diamond Plus, Triangle and Le Professional or "Le Pro") maintain their shape much better, but because of their hardness, chalk tends to not hold as well as it does on softer tips. The hardness of a leather tip is determined from its compression and tanning during the manufacturing process.

All cue tips once were of a one-piece construction, as are many today (including LePro and Triangle). More recently some tips are made of layers that are laminated together (major brands include Kamui, Moori and Talisman). Harder tips and laminated tips hold their shape better than softer tips and one-piece tips. Laminated tips generally cost more than one-piece tips due to their more extensive manufacturing process. A potential problem with layered tips is delamination, where a layer begins to separate from another or the tip completely comes apart. This is not common and usually results from improper installation, misuse of tip tools, or high impact massé shots. One-piece tips are not subject to this problem, but they do tend to mushroom more easily.

These days there are synthetic, faux-leather or even rubber cue tips available that have similar playing characteristics to animal-hide tips. Often these are less affected by moisture and humidity than leather tips, tend less to bulge and mis-shapen, and are suitable substitutes for the average player.

Ferrule

The end of the shaft has a cuff known as the ferrule, which is used to hold the cue tip in place and to bear the brunt of impact with the cue ball so that the less resilient shaft wood does not split. Ferrules are no longer made of ivory, but, rather, are now made of carbon fiber, or a plastic such as melamine resin, or phenolic resin, which are extremely durable, high-impact materials that are resistant to cracking, chipping, and breaking. Brass ferrules are sometimes used, especially for snooker cues. Titanium ferrules (lighter than brass) are fitted by some players to help reduce cue ball deflection when using side-spin.

Joint

The heavy, lower piece of the cue is the cue butt, and the smaller, narrower end is the shaft. The two cue pieces are attached at the joint; normally a screw rising from butt end's joint (male) is threaded into a receptacle on the shaft (female), or vice versa. The joints are made of various materials, most frequently a plastic, brass, stainless steel, or wood outer layer, but some custom cues are made of bone, antlers, or other more expensive materials that are less common, but serve the same effect. Most snooker cues have brass-to-brass joints. The internal male and female connection points are almost always brass or steel because they respond less to temperature changes and thus expand and contract less than other materials, preserving the life of the cue. Joints have different sizes as well as different male and female ends on the shaft and butts of the cues. Traditional designs employ a fully threaded connection, while newer versions (marketed under such names as Uni-loc, Accu-loc, Speed-loc, and Tru-loc) employ half-threaded "quick pin release" connections that allow players to assemble and disassemble their cues faster.

Butt

The bulk of the weight of the cue is usually distributed in the cue butt portion. Whether the weight be 16 oz. or 22 oz., the weight change is mainly in the butt (usually in the core, under the wrap). Butts have varying constructions, from three-piece to one-piece, as well as other custom versions that people have developed. These translate into different "feels" because of the distribution of weight as well as the balance point of the cue. Traditionally, players want the balance point of a cue near the top end of the wrap or around 7 inches from where they grip the butt. Some brands and most custom cuemakers offer weights, usually metal discs of 1 to 2 ounces, that can be added at one or more places to adjust the balance and total weight and feel of the cue.

The cue butt is often inlaid with exotic woods such as bocote, cocobolo and ebony as well as other materials such as mother of pearl. Usually parts of the butt are sectioned off with decorative rings. The use of various types of wraps on the cue butt, such as Irish linen or leather, provide a player with a better grip as well as absorbing moisture. Low-priced cues usually feature a nylon wrap which is considered not as good a "feel" as Irish Linen. Fiberglass and Graphite cues usually have a "Veltex" grip that is made of fiberglass/graphite, but is smoother and not glossy. Some people also prefer a cue with no wrap, and thus just a glossed finish on wood. Sometimes these no-wrap cues are more decorated because of the increased area for design and imagination. The butts of less expensive cues are usually spliced hardwood and a plastic covering while more high-end cues use solid rosewood or ebony. Snooker cues might be just the wood, waxed or oiled (bees wax, linseed oil).

Bumper

The final part a cue is the bumper, made of rubber (pool) or leather (snooker). Though often considered less important than other parts of a cue, this part is essential for protecting a cue. The bumper protects the cue when it rests on the ground or accidentally hits a wall, table, etc. Without the bumper, such impacts might crack the butt over an extended period of time. The "feel" of the cue (see below) is also an issue – without the bumper, the resonance of the cue hitting the cue ball may vibrate differently than in a cue with a properly attached, tight bumper. Though small, the bumper also adds some weight on the end of the cue, preserving a balance that also impacts the feel of a cue.

Materials and design

A cue can be either hand- or machine-spliced. The choice of materials used in the construction of the cue butt and the artistry of the design can lead to cues of great beauty and high price. Good quality pool cues are customarily made from straight-grained hard rock maple wood, especially the shaft. Snooker cues, by contrast, are almost always made of ash wood, although one might come across one with a maple shaft. Maple is stiffer than ash, and cheaper. Cues are not always for play, some are purely collectible and can reach prices of tens of thousands of dollars for the materials they are made of and their exquisite craftsmanship.

A good cue needn't be expensive. These "collector" cues have fine workmanship and use top quality materials. They are designed with ornate inlays in varying types of wood, precious metals and stones, all in a multitude of styles and sometimes displaying works of art.[12] The inlays are stained, translucent, transparent or painted. These cues are also valued because of how well they perform. Competitors of custom cue makers and mass-production manufacturers usually try to make cues look like they are made of expensive materials by using overlays and decals. Although these lower the cost of the cues, they do not degrade the cues' effectiveness in game play. Another mark of quality is the precision with which inlays are set. High quality inlays fit perfectly with no gaps; they are symmetrical on all sides, as well as cut cleanly so that all edges and points are sharp, not rounded. The use of machines has aided much in the production of high quality inlays and other ornaments.

Notable makers

There have been a number of cue makers over the years; among them are George Balabushka,[13] Herman Rambow, John Parris, Hunt & O'Byrne, Lucasi, Meucci, Palmer, Han’s Delta, Predator, Longoni, Samsara, South West, Szamboti, and Tascarella, whose cues are often very valuable to collectors.

See also

References

- Shamos, Mike (1999). The New Illustrated Encyclopedia of Billiards. New York: Lyons Press. ISBN 9781558217973.

- "Cue Maker and Cues Glossary". EasyPoolTutor. 2003–2007. Archived from the original on 11 December 2007. Retrieved 1 December 2007.

- Everton, Clive (1986). The History of Snooker and Billiards (rev. ver. of The Story of Billiards and Snooker, 1979 ed.). Haywards Heath, UK: Partridge Pr. pp. 8–11. ISBN 1-85225-013-5.

- Oxford English Dictionary (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford U. Pr. 1989. "billiard stick" entry.

- Phelan, Michael (1859). The Game of Billiards. New York: D. Appleton & Co. p. 44.

- Kilby, Ronald (May 23, 2009). "So What's a Carom Cue?". CaromCues.com. Medford, OR: Kilby Cues. Archived from the original on June 24, 2008. Retrieved November 20, 2009.

- See online and offline retailers. Virtually all modern snooker cues are 56.5 to 59 inches, with a 57 inch length accounting for about 90% of the market (of major manufacturers, only one defaults to 58 inches). Weights range from 15 to 19 ounces (0.48–54–kg) High-end cues are almost always compatible with one or more butt extension types, and often include one.

- "Official Rules of the Games of Snooker and English Billiards" (PDF). wpbsa.com. World Professional Billiards and Snooker Association. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- "News of the month". The Billiard Player. No. December 1938. p.7.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Clare, Norman. Billiards and Snooker Bygones. Shire Publications. ISBN 9780852637302.

- Mataya Laurance, Ewa; Thomas C. Shaw (1999). The Complete Idiot's Guide to Pool & Billiards. New York: Alpha Books. p. 79. ISBN 0-02-862645-1.

- "Best Pool Cues and Cuemakers Throughout History – cuezilla.com". Cuezilla.com. Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- Martin, R.; Rosser Reeves (1993). The 99 Critical Shots in Pool: Everything You Need to Know to Learn and Master the Game. Other Press. Times Books. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-8129-2241-7. Retrieved March 26, 2019.