Bingham, Nottinghamshire

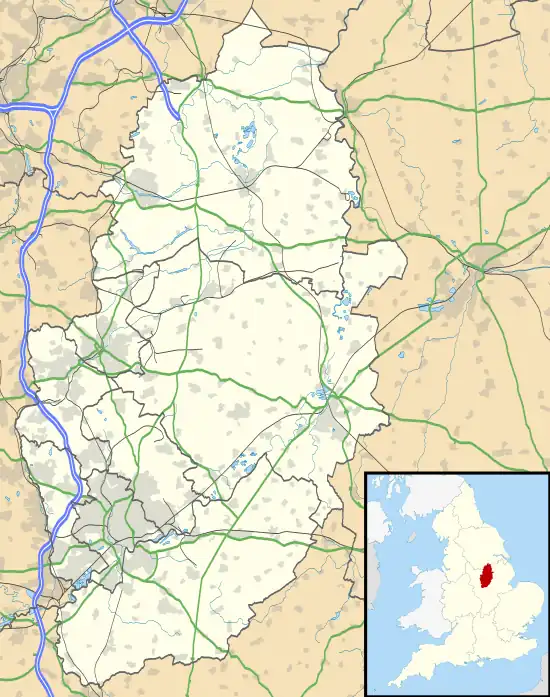

Bingham is a market town and civil parish[1] in the Rushcliffe borough of Nottinghamshire, England, 9 miles (14 km) east of Nottingham, 12 miles (18.8 km) south-west of Newark-on-Trent and 15 miles (23.3 km) west of Grantham. The town had a population of 9,131 at the 2011 census (up from 8,655 in 2001), with the population now sitting at 10,108 from the results of the 2021 census data.[2]

| Bingham | |

|---|---|

Bingham Market Square | |

Bingham Location within Nottinghamshire | |

| Population | 10,108 (2021 UK census) |

| OS grid reference | SK 70334 39950 |

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | NOTTINGHAM |

| Postcode district | NG13 |

| Dialling code | 01949 |

| Police | Nottinghamshire |

| Fire | Nottinghamshire |

| Ambulance | East Midlands |

| UK Parliament | |

| Website | http://bingham-tc.gov.uk |

It is twin towns with Wallenfels in Bavaria, Germany. Music groups have visited to and from the twin towns, and a beer festival is held in Bingham every year.

Geography

Bingham lies near the junction of the A46 (following an old Roman road, the Fosse Way) between Leicester and Newark-on-Trent and the A52 between Nottingham and Grantham. Neighbouring communities are Radcliffe-on-Trent, East Bridgford, Car Colston, Scarrington, Aslockton, Whatton-in-the-Vale, Tithby and Cropwell Butler.

History

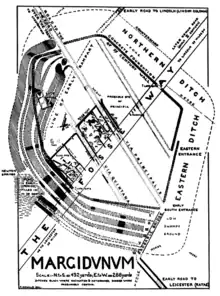

Margidunum

The first known people to settle at this area were the Coritani, a Briton tribe that governed most of the East Midlands who would have called the fort "Marigidun", which meant "fort-of-the-king's plain". This name would later be latinised to "Margidunum". The Romans built a fortress at this site, the ruins of which lay north of Bingham, and a settlement at the river crossing at Ad Pontem (East Stoke) on the Fosse Way, which ran between Isca (Exeter) and Lindum (Lincoln).[3]

Anglo-Saxons

The area was called Byngehamshou Hundred by the Anglo-Saxons and Binghamshou Wapentake by the Danish. It would also have been called Bynnaingham, then Bynningaham, and later morphed into Byngeham. This name comes from the chief of the Angle tribe that settled the town, named “Bynna”, followed by the connective “ing” meaning “of”, and “ham” meaning “homestead”. Hou, meaning “hill”, would have referred to a meeting point of the Hundred Court, who met in the Moot-House Pit, which is on a hill near the Fosse Way. Later, the town would be referred to “Binghehā” in the Domesday Book..[4]

This Anglo-Saxon village, founded around the start of the 7th century, would have been oval shaped, surrounded by a ditch and huts. The Bynna “kindred” (an anglo-saxon pagan family unit) placed their village next to a marshland, a source of water which would later be drained, leaving extremely valuable fertile lands for farming. Bingham would have converted to Christianity at around the same time as the rest of the Kingdom of Mercia, around the second half of the 7th century.

Normans

Following the Norman conquest of England, the Domesday Book of 1086 allows us to estimate that the village had a population of around 300, and that the majority of freeholders in the district were Danes. The first Norman owner of the manor surrounding Bingham was Roger de Busli, however he died without an heir after only a few years and so Bingham Manor became part of the King’s demesne, and even now much of Bingham remains crown land. The Domesday book valued the town and surrounding area at £10 13s, which today is worth around £90,000.[4]

Bingham acquired a market charter in 1341.

Tudors

During the reign of Elizabeth I Tudor, the Bingham Manor was owned by Sir Bryan Stapleton, who lived in Carlton, although he lent out the manor to a man named Thomas Leeke, who was possibly the maternal grandfather of Bess of Hardwick.[5] At this time, farming in Bingham was quite collectivistic, with lots of common area in the Bingham moors to keep pigs and to collect firewood. In order to maintain these common lands, the Manor Court, which met around the Church gate, contained 5 elected officers. A foreman of the fields, A hayward in charge of the common grazing land, a pindar in charge of the pinfold (an enclosure for stray livestock), a ringer for hogs and swine, and a woodward who made sure that not too many trees were chopped down.[4]

Civil War

During the English Civil War, Bingham was stood in the middle of the Parliamentary stronghold of Nottingham and the Royalist stronghold in Newark. Prince Rupert, on his way to relieve Newark, encamped in the fields surrounding Bingham. Given that 700 roundhead soldiers sought refuge in Bingham, a conclusion could be drawn that it was generally sympathetic to the Parliamentary cause, especially given that many men of Bingham would have died in battles around Nottingham.[4]

Industrial Revolution

In 1801, the population of Bingham was 1,082. This increased slowly to 2,054 in 1851, but fell back again and in 1901 was just 1,604. In 1951 it was 1,692, and since then Bingham has expanded vastly.[6] Although some buildings in the centre of the town such as Church of St Mary and All Saints were built in the 18th century, the majority of the buildings in Bingham are relatively new and much of the growth in the town happened after the second World War.

The first major wave of growth in the town happened around the time of the industrial revolution as the workforce expanded and more housing was needed for the growing population of the town. This was compounded by the arrival of the railways into the town in 1851, although as England's agricultural sector began to decline and the cottage industry of lace and stocking knitting were overtaken by factories in Nottingham, Bingham would plunge into high levels of poverty and unemployment. A sharp decline in population and growth followed this, and the town would not recover until after the second World War.

Post-war Redevelopment

After the war, the Bingham Rural District Council inspected the state of over 2,000 houses in the area to see if they needed to be demolished or could be repaired for the redevelopment. It was decided in the redevelopment that farming property should remain out in the countryside instead of mixed in with the other residential properties. Some notable buildings that were destroyed are Stanhope Workhouse on Stanhope Way and the Rectory on East Street, drastically changing the look of the town. The 1960s and 70s saw almost constant development with new houses being built to accommodate the local population. More recently, a new housing development in the north of Bingham named the Romans' Quarter (after the nearby Ancient Roman ruins of Margidunum) started around 2018 with plans for around 1,000 new houses.[7]

Amenities

Schools and Library

Bingham has five schools, Robert Miles Infants School opened in 1909, Robert Miles Junior School built in the 1960s on the site of the Rectory, Carnarvon Primary School, Bingham Primary School & Nursery, and Toot Hill Comprehensive School. Two other schools operated in the past, the Church School and the Wesleyan School, the latter of which shut down in 1909 and was demolished in 2002.[8][9]

Bingham's library has existed in some form since around the late 1950s, starting as a "charity penny library" in a lean-to on 7-9 Newgate Street. Eventually the County Library took it over, and in 1973 it was moved Eaton Place, where it remains to this day.[10]

Churches

The Anglican parish Church of St. Mary and All Saints, Bingham, occupies a Grade I listed medieval building restored in 1845–1846 and again in 1912. It has a peal of eight bells and a 19th-century organ. It belongs to the Diocese of Southwell and Nottingham.

A new Bingham Methodist Church and social centre, built by public subscription, opened on 1 April 2016 at Eaton Place, on the site of the earlier church.[11] It belongs to the Grantham and Vale of Belvoir Circuit.[12] Archive documents for Bingham Methodist Circuit date back to 1843.[13]

Economy

The open-air food market in the central Market Place takes place every Thursday and a farmers' market there on the third Saturday of the month. Bingham provides shopping, medical and other services to surrounding villages. Planning permission has been gained to build a large supermarket near the town centre, but construction has yet to begin. In March 2015 planning permission was given for two other chain supermarkets.[14]

To the north of the town there is an industrial estate holding about 40 businesses. The largest include GWIBS 24/7, Focus Label Machinery, Trent Designs, XACT Document Solutions, The Workplace Depot and Water at Work, and a business club.[15]

Leisure and sports

Of the six pubs in the town, four remain as such: The Butter Cross (Wetherspoons, formerly The Crown), The Horse & Plough (Castle Rock Brewery), The White Lion and The Wheatsheaf. There is also a bar/bistro called Gilt.

Bingham Arena has sports facilities, a swimming pool, conference facilities and a large assembly hall. This replaced the former Bingham Leisure centre, next to Toot Hill School.

Bingham has Scout troops with about 140 young members: 1st Bingham Scouts includes Beavers and Cubs.[16]

The town's sports clubs are:

Media

Local news and television programmes are provided by BBC East Midlands and ITV Central. Television signals are received from the Waltham TV transmitter,[23] BBC Yorkshire and Lincolnshire and ITV Yorkshire can also be also received from the Belmont TV transmitter. [24]

Local radio stations are BBC Radio Nottingham, Gem, Capital Midlands, Smooth East Midlands, Greatest Hits Radio Midlands and The Eye Radio.

The Nottingham Evening Post and Newark Advertiser are the local newspapers that serve the town.

Film and TV locations

Bingham was a location in Midlands film director Shane Meadows' film Twenty Four Seven, which contained scenes shot at Toot Hill top field, the Linear Walk, and Bingham Boxing Club. Bingham has also appeared in two episodes of Auf Wiedersehen, Pet,[25] and in some episodes of Crossroads, Woof! and Boon.

Dickinson's Real Deal was filmed at the Bingham Leisure Centre in 2015 and broadcast on TV on ITV1 in March 2016. Four in a Bed, Series 11 Episode 18, was filmed at Bingham Townhouse Hotel in May 2016 and first aired in the late autumn of 2016.

Notable people

In birth order:

- Robert Lowe, 1st. Viscount Sherbrooke (1811–1892), statesman born in Bingham into the family of the local rector.

- Frank Miles (1852–1891), artist of pastel portraits of society ladies, an architect and a keen plantsman.

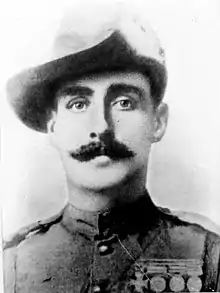

- Harry Churchill Beet (1873–1946), awarded a Victoria Cross for valour at Wakkerstroom, South Africa, in the Second Boer War on 22 April 1900, born at Brackendale Farm near Bingham.[26]

- Mary Joynson (1924–2013), director of Barnardo's from 1973 to 1984, born in Bingham.[27]

- Spencer Cozens (born 1965), a Bingham-born musician, writer and producer.

Sport

- Thomas Foster (fl. 1820s), first-class cricketer with Nottingham Cricket Club (1827–28), reportedly born in Bingham.

- Thomas Brown (1848–1919), first-class cricketer (Nottinghamshire), born in Bingham.

- Philip Miles (1848–1933), first-class cricketer (Nottinghamshire), born in Bingham.

- John Brown (born 1862), first-class cricketer (Nottinghamshire) born in Bingham.

- Albert Widdowson (1864–1938), first-class cricketer (Derbyshire), born in Bingham.

- Stafford Castledine (1912–1986), first-class cricketer (Nottinghamshire), born in Bingham.[28]

- Jonathan Stenner (born 1966), cricketer and gastroenterologist, born in Bingham.

- Joe Heyes (born 1999), from Bingham, a professional rugby union player for Leicester Tigers.

Transport

Trentbarton provides a frequent public bus service into Nottingham.[29] Bingham's main railway station provides an hourly service to and beyond Nottingham and Grantham and to Skegness along the Poacher Line. Another station south of Bingham named Bingham Road was opened on the Nottingham-Leicester-Northampton Line. It closed in 1951 to passengers and 1964 to freight. The station site has been demolished and the trackbed is now used as a greenway.

Bus services

- Vectare:[30] 833 Bingham Circular via Cropwell Bishop, Langar, Orston and Aslockton

- Centrebus:[31]

- X6: Bingham–Grantham Trentbarton:[32]

- Rushcliffe Mainline: Bingham–Radcliffe–West Bridgford–Nottingham (fastest Bingham–Nottingham route)

- Rushcliffe Villager 1: Bingham–East Bridgford–Radcliffe–West Bridgford–Nottingham.

The A46, to the west of the town, was upgraded and completed in 2013 as a grade-separated dual carriageway. The Widmerpool-Newark Improvement has been diverted to the west of the former Roman town to preserve archaeological remains. The A52 bypass to the south of the town opened in December 1986.

Signpost gallery

References

- "Bingham Town Council". Bingham Town Council. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- City Population.

- "Elston Parish Council". Newark and Sherwood District Council. Archived from the original on 30 August 2010. Retrieved 5 November 2008.

- Wortley, Adelaide Louisa (1953). History of Bingham. Oxford: A. R. Mowbray & Co.

-

- Durant, David N. (1977). Bess of Hardwick: Portrait of an Elizabethan Dynasty. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-77305-4.

- Heritage site retrieved 6 July 2021.

- "Romans Quarter Phase 3". Barratt Homes.

- "Parish Magazine". Bingham Heritage Trails Association.

- "Eyes of a Teacher". Bingham Heritage Trails Association.

- "9 Newgate Street". Bingham Heritage Trails Association.

- "Bingham Methodist Church". Facebook. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- "About Us". Bingham Methodist. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- Nottinghamshire Archives Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- "Budget supermarkets Aldi and Lidl given green light in Bingham". Nottingham Post. 19 March 2015. Archived from the original on 21 July 2015.

- "Home". Bingham Business Club. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- "Home". 1st Bingham Scouts. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- "Home". Bingham Town FC. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- "Home". Bingham Cricket Club. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- "Home". Bingham Archery Club. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- "Home". Bingham Sub-Aqua Club. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- "Home". Bingham Penguins. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- "Home". Vale Judo Club. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- "Full Freeview on the Waltham (Leicestershire, England) transmitter". UK Free TV. 1 May 2004. Retrieved 27 September 2023.

- "Belmont (Lincolnshire, England) Full Freeview transmitter". UK Free TV. 1 May 2004. Retrieved 27 September 2023.

- "Nottinghamshire Locations Continued..." The Original Auf Wiedersehen Pet Homepage. Archived from the original on 2 March 2008. Retrieved 5 November 2008.

- "No. 27283". The London Gazette. 12 August 1902. p. 1059.

- Philpot, Terry (2 May 2013). "Mary Joynson obituary". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- "Stafford Castledine". Cricket Archive. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- "Home". Xprss.info. Archived from the original on 15 March 2005. Retrieved 5 November 2008.

- "Home".

- "Centrebus". Archived from the original on 7 February 2019. Retrieved 4 February 2019.. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- Trent Barton.

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)