Bird of Paradise (1932 film)

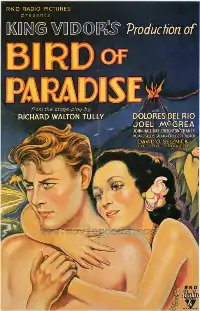

Bird of Paradise is a 1932 American pre-Code romantic adventure drama film directed by King Vidor and starring Dolores del Río and Joel McCrea. Based on the 1912 play of the same name by Richard Walton Tully, it was released by RKO Radio Pictures.

| Bird of Paradise | |

|---|---|

Film poster | |

| Directed by | King Vidor |

| Screenplay by | Wells Root Wanda Tuchock Leonard Praskins |

| Based on | The Bird of Paradise 1912 play by Richard Walton Tully |

| Produced by | David O. Selznick King Vidor |

| Starring | Dolores del Río Joel McCrea |

| Cinematography | Lucien Andriot Edward Cronjager Clyde De Vinna |

| Edited by | Archie Marshek |

| Music by | Max Steiner |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | RKO Radio Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 80 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $752,000[1] |

| Box office | $753,000[1] |

In 1960, the film entered the public domain in the United States because the claimants did not renew its copyright registration in the 28th year after publication per the Copyright Act of 1909.[2]

Plot

As a yacht sails into an isolated tropical island chain somewhere in the Pacific Ocean, a large number of islanders in outrigger canoes paddle out to greet it. The islanders dive for trinkets the yacht's crew throws them. A shark arrives, setting off a panic as much with the crew as the islanders. Johnny Baker (Joel McCrea) attempts to catch it hand casting with a large hook, but is yanked overboard when a loop of line attached to the impaled shark cinches around his ankle. Comely native swimmer Luana (Dolores del Río) cuts through the rope with a knife she had earlier been thrown as a trinket, saving his life.

At a welcome banquet that night, Johnny sees young island men ritually carry off young maidens, and seeks to do the same with Luana, but is stopped and castigated by the local chieftain, her father. With brief nudity and underwater swimming scenes, they swiftly fall in love. Later, the yacht moves on, but leaves Johnny on the island for an adventure. He discovers Luana has been promised to another man – a prince on a neighboring island. She is spirited away to this island for the arranged marriage, while Johnny is waylaid. During an elaborate dance sequence, Johnny has made his way to the island in the nick of time, runs into a circle of fire, and rescues her as the natives kneel to the fire. Johnny and Luana then travel to another island where they hope to live out the rest of their lives. He builds her a house with a roof of thatched grass. However, their idyll is smashed when the local volcano on her home island begins to erupt. She confesses to her lover that her sacrifice alone can appease the mountain. Her people take her back. When Johnny goes after her, he is wounded in the shoulder by a spear and tied up. The people decide to sacrifice both of them to the volcano, but on the way, the couple are rescued by Johnny's friends and taken aboard the yacht.

Johnny's wound is tended to, but his friends wonder what will become of the lovers. Luana does not fit into Johnny's world. When Johnny is sleeping, Luana's father demands her back. She goes willingly, believing that only she can save her people by voluntarily throwing herself into the volcano.

Cast (in credits order)

- Dolores del Río as Luana

- Joel McCrea as Johnny Baker

- John Halliday as Mac

- Richard "Skeets" Gallagher as Chester

- Bert Roach as Hector

- Lon Chaney Jr. (billed as Creighton Chaney)[3] as Thornton

- Wade Boteler as Skipper Johnson

- Reginald Simpson as O'Fallon

Production

Director King Vidor, under contract to M-G-M, was loaned to RKO producer David Selznick (son-in-law to Louis B. Mayer) to make the “South Seas” romance. Filmed on location in Hawaii, Vidor and writer Wells Root arrived on the island territory and began shooting background footage without a completed script (Actors McCrea and del Rio were delayed due to engagements on other projects,) .[4]

The native dance sequences were boom-shot in Hollywood and choreographed by an uncredited Busby Berkeley.[5]

Bird of Paradise was almost the first sound film to utilize a full symphonic score from beginning to end. Producer David O. Selznick and composer Max Steiner had both been experimenting with this idea, while other studios had begun development along similar lines, such the score by Alfred Newman for Samuel Goldwyn's Street Scene. However, it was Steiner who first received screen credit for composition of a score which, other than a few brief pauses during the film, was almost entirely through-composed (from beginning to end).[6]

Reception

_2.jpg.webp)

Bird of Paradise created a scandal after its release owing to a scene which appeared to show Dolores del Río swimming naked. She was, in fact, wearing a flesh-coloured G-string. The film was made before the Production Code was strictly enforced, so brief nudity in American movies was not unknown.[7] Film director Orson Welles said del Río represented the highest erotic ideal with her performance in the film.[8]

Box Office

The film lost an estimated $250,000 at the box office.[1]

The film is recognized by American Film Institute in these lists:

- 2002: AFI's 100 Years...100 Passions – Nominated[9]

Theme

.jpg.webp)

In the early 1930s, Hollywood produced a number of pictures that exploited popular interest in “exotic” tropical locations, though these regions were fully penetrated by Western culture by the early 20th Century, including Hawaii.[10] Films of this genre ranged from elevated ethnological studies such as F.W. Murnau’s and Robert Flaherty's Tabu: A Story of the South Seas (1931) to the Tarzan adventure series and King Kong in 1932 and 1933.

Vidor presents this “tragic” romance as a clash between modern “civilization” and a sexual idyll enjoyed by Rousseauian-like Noble savages. The sexual promiscuity and eroticism exhibited in Bird of Paradise is a measure of the as yet unenforced prohibitions of the Breen Office with its “nude swimming...lovers hanging from bamboo poles trying to kiss and Doloros del Rio sucking an orange, then transferring the juice to McCrea's fevered mouth.”[11]

.jpg.webp)

Though the American (McCrea) and his Hawaiian lover (del Rio) attempt to transcend the racist and sexual strictures that doom their relationship, Vidor, although not personally a racist, ended the film with what some interpret as an anti-miscegenation message. Selznick's story line that “climax[s] with the girl tossed into a volcano” is both an example of the producer's predilection for tragic melodrama and, as seen by some, a Vidorian “tongue-in-cheek” cautionary tale concerning the fate of racially mixed couples.[12]

Footnotes

- Richard Jewel, 'RKO Film Grosses: 1931–1951', Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, Vol 14 No 1, 1994 p39

- Pierce, David (June 2007). "Forgotten Faces: Why Some of Our Cinema Heritage Is Part of the Public Domain". Film History: An International Journal. 19 (2): 125–43. doi:10.2979/FIL.2007.19.2.125. ISSN 0892-2160. JSTOR 25165419. OCLC 15122313. S2CID 191633078.

- Bird of Paradise (1932) cast list at IMDb

- Baxter 1976 p. 46: “...a classic South Seas triangle story - boy, girl, volcano...” And “...racing the deadlines for other films of its stars

Durgnat and Simmon 1988 p. 96: “...limited availability of the two stars...” And “[shooting] plagued by storm delays...” - Baxter 1976 p. 48:

Durgnat and Simmon 1988 p. 96: “...Busby; Berkeley's booms [produce] a pageant syle” in the dance sequences. - Darby, William & DuBois, Jack American Film Music p.18

- Sex in Cinema, AMC filmsite

- Bird of Paradise, 1932 pre-code

- "AFI's 100 Years...100 Passions Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- Durgnat and Simmon 1988 p. 134: Vidor's depiction of “[White man's] gunfire as black magic would have had more plausibility set in the eighteen century...”

- Baxter 1976 p. 48-49:

Durgnat and Simmon 1988 p. 135: “Vidor's fascination with conflicts of cultures, languages and races is pared down to ‘civilization’ vs. sexuality.” And: “Vidor enjoys the civilization/sexuality clash.” - Durgnat and Simmon 1988 p. 136-137: “...nothing prepares us for Selznick's volcano sacrifice.” And “...Old World cultures are there for Americans and their lovers to transcend...If the film renounces miscegenation, that's not Vidor's fault... [the movie] yearns the other way. But the strictures against miscegenation were so strong that fatalism was built into [the story's] premise.”

See also

References

- Baxter, John. 1976. King Vidor. Simon & Schuster, Inc. Monarch Film Studies. LOC Card Number 75-23544.

- Durgnat, Raymond and Simmon, Scott. 1988. King Vidor, American. University of California Press, Berkeley. ISBN 0-520-05798-8

External links

- Bird of Paradise on YouTube

- Bird of Paradise at IMDb

- Bird of Paradise is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive

- Bird of Paradise at AllMovie

- Bird of Paradise at the TCM Movie Database

- Bird of Paradise at the American Film Institute Catalog