Bhirrana

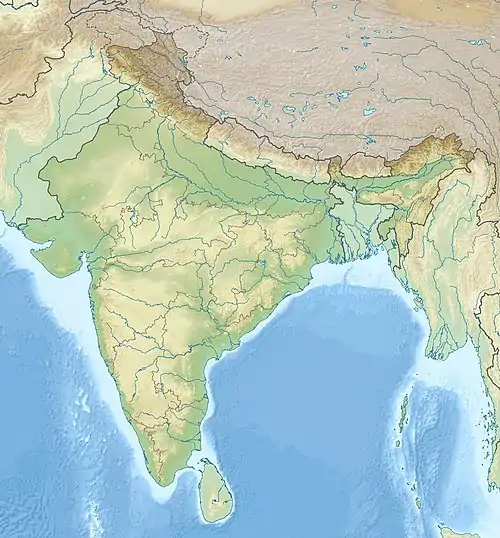

Bhirrana, also Bhirdana and Birhana, (Hindi: भिरड़ाना; IAST: Bhirḍāna) is an archaeological site, located in a small village in the Fatehabad district of the north Indian state of Haryana.[web 1][5][web 2] Bhirrana's earliest archaeological layers predates Indus Valley civilisation times, dating to the 8th-7th millennium BCE.[2][1][6][3][4][web 2] The site is one of the many sites seen along the channels of the seasonal Ghaggar river,[7][4] thought by some to be the Rigvedic Saraswati river.[web 2][4]

| |

Shown within Haryana  Bhirrana (India) | |

| Location | Haryana, India |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 29°33′15″N 75°32′55″E |

| Length | 190 m (620 ft) |

| Width | 240 m (790 ft) |

| History | |

| Founded | Approximately 8th-7th m. BCE[1][2][3][4] |

| Abandoned | Approximately 2600 BCE[1][2][3][4] |

| Periods | Hakra Wares to Mature Harappan |

| Cultures | Hakra Ware culture, Indus Valley civilization |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 2003–2006 |

Location

The site is situated about 220 km (140 mi) to the northwest of New Delhi on the New Delhi-Fazilka national highway and about 14 km northeast of the district headquarters on the Bhuna road in the Fatehabad district, North of Bhirrana, off the Shekhupur road. The site is one of the many sites seen along the paleo-channels of channels of the seasonal Ghaggar River which flows in modern Haryana from Nahan to Sirsa.

The mound measures 190 m (620 ft) north-south and 240 m (790 ft) east-west and rises to a height of 5.5 m (18 ft) from the surrounding area of flat alluvial sottar plain.

Excavations

The Excavation Branch-I, Nagpur of the Archaeological Survey of India excavated this site for three field seasons during 2003–04, 2004–05 and 2005–06. Several publications have been written on it by Rao et al.

Dating

Rao, who excavated Bhirrana, claims to have found pre-Harappan Hakra Ware in its oldest layers, dated at the 8th–7th millennium BCE.[8][9][10][lower-alpha 1] He proposes older datings for Bhirrana compared to the conventional Harappan datings,[lower-alpha 2] yet sticks to the Harappan terminology.[13] This proposal is supported by Sarkar et al. (2016), co-authored by Rao, who also refer to a proposal by Possehl, and various radiocarbon dates from other sites, though giving 800 BCE as the enddate for the Mature Harappan phase:[10][lower-alpha 3] Rao 2005, and as summarized by Dikshit 2013, compares as follows with the conventional datings, and Shaffer (Eras).[13][10][14][15]

| Culture (Rao 2005) |

Date (Sarkar 2016) |

Phase (Sarkar 2016) |

Period (Dikshit 2013) |

Conventional date (HP) | Harappan Phase | Conventional date (Era) | Era |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Period IA: Hakra Wares Culture | 7500–6000 BCE | Pre-Harappan | Pre-Harappan Hakra Period (Neolithic) | 7000–3300 BCE | Pre-Harappan | c. 7000 – c. 4500 BCE | Early Food Producing Era |

| Period IB: Early Harappan | 6000–4500 BCE | Early Harappan | Transitional Period | ||||

| Period IIA: Early Mature Harappan | 4500–3000 BCE | Early Mature Harappan | Early Harappan Period | c. 4500–2600 BCE | Regionalisation Era | ||

| 3300–2600 BCE | Early Harappan | ||||||

| Period IIB: Mature Harappan | 3000–800 BCE | Mature Harappan | Mature Harappan Period | ||||

| 2600–1900 BCE | Mature Harappan | 2600–1900 BCE | Integration Era | ||||

| Late Harappan Period | 1900–1300 BCE | Late Harappan | 1900–1300 | Localisation Era | |||

Cultures

According to Rao, the excavation has revealed these cultural periods; Period IA: Hakra Wares Culture, Period IB: Early Harappan Culture, Period IIA: Early Mature Harappan and Period IIB: Mature Harappan Culture.[16][10][9] According to the Archaeological Survey of India, the excavation has revealed the remains of the Harappan culture right from its nascent stage, i.e., Hakra Wares Culture (antedating the Known Early Harappan Culture in the subcontinent, also known as Kalibangan-I.) to a full-fledged Mature Harappan city.[web 2][lower-alpha 1]

Period IA: Hakra Wares Culture

Prior to the excavation of Bhirrana, no Hakra Wares culture, predating the Early Harappan had been exposed in any Indian site. According to the ASI, for the first time, the remains of this culture have been exposed at Bhirrana. This culture is characterised by structures in the form of subterranean dwelling pits, cut into the natural soil. The walls and floor of these pits were plastered with the yellowish alluvium of the Saraswati valley. The artefacts of this period comprised a copper bangle, a copper arrowhead, bangles of terracotta, beads of carnelian, lapis lazuli and steatite, bone point, stone saddle and quern.[17] The pottery repertoire is very rich and the diagnostic wares of this period included Mud Applique Wares, Incised (Deep and Light), Tan/Chocolate Slipped Wares, Brown-on-Buff Wares, Bichrome Wares (Paintings on the exterior with black and white pigments), Black-on-Red Ware and plain red wares.[web 2]

Period IB: Early Harappan Culture

The entire site was occupied during this period. The settlement was an open air one with no fortification. The houses were built of mud bricks of buff colour in the ratio of 3:2:1. The pottery of this period shows all the six fabrics of Kalibangan – I along with many of the Hakra Wares of the earlier period. The artifacts of this period include a seal of quarter-foil shape made of shell, arrowheads, bangles and rings of copper, beads of carnelian, jasper, lapis lazuli, steatite, shell and terracotta, pendents, bull figurines, rattles, wheels, gamesmen, and marbles of terracotta, bangles of terracotta and faience, bone objects, sling balls, marbles and pounders of sandstone.

Period IIA: Early Mature Harappan Culture

This period is marked by transformation in the city lay-out. The entire settlement was encompassed within a fortification wall. The twin units of the town planning; Citadel and Lower Town came into vogue. The mud brick structures were aligned with a slight deviation from the true north. The streets, lanes and by-lanes were oriented in similar fashion. The pottery assemblage shows a mixed bag of Early Harappan and Mature Harappan forms. The artifacts of the period included beads of semi-precious stones (including two caches of beads kept in two miniature pots), bangles of copper, shell, terracotta and faience; fishhook, chisel, arrowhead of copper; terracotta animal figurines and a host of miscellaneous artifacts.

Period IIB: Mature Harappan Culture

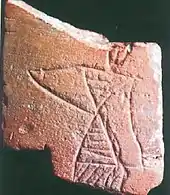

The last period of occupation at the site belongs to the Mature Harappan period with all the characteristic features of a well-developed Harappan city. The important artifacts of the period consisted of Seals of steatite, bangles of copper, terracotta, faience and shell, inscribed celts of copper, bone objects, terracotta spoked wheels, animal figurines of terracotta, beads of lapis lazuli, carnelian, agate, faience, steatite, terracotta and stone objects. A replica of the famous "Dancing Girl" from Mohenjodaro is found engraved[web 1] on a potsherd in the form of a graffiti.[18] The massive fortification wall[17] of the town was made of mud bricks. The houses were made of mud bricks (sun-baked bricks). Wide linear roads can be seen separating the houses. A circular structure of baked earth is probably a "tandoor" – a community kitchen still seen in rural India. Presence of the baked bricks is seen used in the main drain provided on the width of the northern arm of the fortification wall to flush out the waste water from the houses.

Dancing girl graffiti

Pottery graffiti at Bhirrana show "mermaid" type deities and dancing girls;[web 1] the latter have a posture similar to Mohenjo-daro's bronze "dancing girls" that the archaeologist L.S. Rao stated that "it appears that the craftsman of Bhirrana had first-hand knowledge of the former."[17][web 3] These deities or dancing girls may represent apsaras, or water nymphs, associated with water rites once widespread in the Indus Valley civilisation.[18]

Other findings

Other significant findings included terracotta wheels with painted spokes.[web 4] People used to live in shallow mud plastered pit dwellings and pits were also used for industrial activity or sacrifices.[17] Multi-roomed houses were exposed at this site, one house with ten rooms and another with three rooms. Another house had a kitchen, court yards, chullah [i.e., chulha, cooking stoves] in the kitchen; beside the chullah, charred grains were also found.[17]

According to Rao, all phases of Indus Valley Civilisation are represented in this site.

See also

- Indus Valley civilisation related

- List of Indus Valley Civilisation sites

- Bhirrana, 4 phases of IVC with earliest dated to 8th–7th millennium BCE

- Kalibanga, an IVC town and fort with several phases starting from Early harappan phase

- Rakhigarhi, one of the largest IVC city with 4 phases of IVC with earliest dated to 8th–7th millennium BCE

- Kunal, cultural ancestor of Rehman Dheri

- List of inventions and discoveries of the Indus Valley civilisation

- Periodisation of the Indus Valley civilisation

- Pottery in the Indian subcontinent

- Bara culture, subtype of Late-Harappan Phase

- Cemetery H culture (2000–1400 BC), early Indo-Aryan pottery at IVC sites later evolved into Painted Grey Ware culture of Vedic period

- Black and red ware, belonging to neolithic and Early-Harappan phases

- Sothi-Siswal culture, subtype of Early-Harappan Phase

- Rakhigarhi Indus Valley Civilisation Museum

- List of Indus Valley Civilisation sites

- History of Haryana

Notes

- According to Dikshit and Rami, the estimation for the antiquity of Bhirrana as pre-Harappan is based on two calculations of charcoal samples, giving two dates of respectively 7570–7180 BCE, and 6689–6201 BCE.[8][9] Hakra Ware culture is a material culture which is contemporaneous with the early Harappan Ravi phase culture (3300–2800 BCE) of the Indus Valley.[11][12][1]

- Sarkar et al. (2016): "Conventionally the Harappan cultural levels have been classified into 1) an Early Ravi Phase (~5.7–4.8 ka BP), 2) Transitional Kot Diji phase (~4.8–4.6 ka BP), 3) Mature phase (~4.6–3.9 ka BP) and 4) Late declining (painted Grey Ware) phase (3.9–3.3 ka BP13,19,20)."[4]

- According to Sarkar et al. (2016), the various cultural levels at Bhirrana, as deciphered from the archaeological artifacts, are pre-Harappan (~9.5–8 ka BP), Early Harappan (~8–6.5 ka BP), Early mature Harappan (~6.5–5 ka BP) and mature Harappan (~5–2.8 ka BP).[10] Compare Madina and Pirak, late Harappan elements until 800 BCE, together with Painted Grey Ware.

References

- Law 2008, p. 83.

- Rao 2005.

- Dikshit 2013.

- Sarkar 2016.

- Kunal, Bhirdana and Banawali in Fatehabad

- Dikshit 2012.

- Singh 2017.

- Dikshit 2013, p. 129–133.

- Mani 2008, p. 237–238.

- Sarkar 2016, p. 2–3.

- Coningham & Young 2015, p. 158.

- Ahmed 2014, p. 107.

- Dikshit 2013, p. 132.

- Shaffer 1992, I:441–464, II:425–446..

- Manuel 2010, p. 148.

- Rao 2005, p. 60.

- Singh 2008, p. 109, 145, 153.

- Mahadevan 2011.

Sources

Printed sources

- Ahmed, Mihktar (2014), Ancient Pakistan – an Archaeological History

- Coningham; Young (2015), The Archaeology of South Asia: From the Indus to Asoka, c.6500 BCE–200 CE, Cambridge University Press

- Dikshit, K.N. (2012). "The Rise of Indian Civilization: Recent Archaeological Evidence from the Plains of 'Lost' River Saraswati and Radio-Metric Dates". Bulletin of the Deccan College Research Institute. 72/73: 1–42. ISSN 0045-9801. JSTOR 43610686.

- Dikshit, K.N. (2013), "Origin of Early Harappan Cultures in the Sarasvati Valley: Recent Archaeological Evidence and Radiometric Dates" (PDF), Journal of Indian Ocean Archaeology (9), archived from the original (PDF) on 18 January 2017

- Law, William Randal (2008). Inter-regional Interaction and Urbanism in the Ancient Indus Valley: A Geologic Provenience Study of Harappa's Rock and Mineral Assemblage. Ann Arbor, MI. p. 83. ISBN 9780549628798.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Mahadevan, Iravatham (2011). "The Indus Fish Swam in the Great Bath: A New Solution to an Old Riddle" (PDF). Bulletin of the Indus Research Centre (2): 19. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 April 2015. Retrieved 5 July 2012.

- Mani, B.R. (2008), "Kashmir Neolithic and Early Harappan : A Linkage" (PDF), Pragdhara 18, 229–247 (2008), archived from the original (PDF) on 18 January 2017, retrieved 17 January 2017

- Manuel, Mark (2010), "Chronology and Culture-History in the Indus Valley", in Gunawardhana, P.; Adikari, G.; Coningham Battaramulla, R.A.E. (eds.), Sirinimal Lakdusinghe Felicitation Volume, Neptune

- Rao, L.S.; Sahu, N.B.; Sahu, Prabash; Shastry, U.A.; Diwan, Samir (2005), "New light on the excavation of Harappan settlement at Bhirrana" (PDF), Purātattva (35)

- Sarkar, Anindya; Mukherjee, Arati Deshpande; Bera, M. K.; Das, B.; Juyal, Navin; Morthekai, P.; Deshpande, R. D.; Shinde, V. S.; Rao, L. S. (2016). "Oxygen isotope in archaeological bioapatites from India: Implications to climate change and decline of Bronze Age Harappan civilization". Scientific Reports. 6: 26555. doi:10.1038/srep26555. PMC 4879637. PMID 27222033.

- Shaffer, J. G. (1992), "The Indus Valley, Baluchistan and Helmand Traditions: Neolithic Through Bronze Age", in Ehrich, R. (ed.), Chronologies in Old World Archaeology (3rd Edition), Chicago: University of Chicago Press

- Singh, Upinder (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India : from the Stone Age to the 12th century. New Delhi: Pearson Education. pp. 109, 145, 153. ISBN 9788131711200.

- Singh, Ajit; Thomsen, Kristina J.; Sinha, Rajiv; Buylaert, Jan-Pieter; Carter, Andrew; Mark, Darren F.; Mason, Philippa J.; Densmore, Alexander L.; Murray, Andrew S.; Jain, Mayank; Paul, Debajyoti (2017). "Counter-intuitive influence of Himalayan river morphodynamics on Indus Civilisation urban settlements". Nature Communications. 8 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-01643-9. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 5705636. PMID 29184098. S2CID 3321708.

Web-sources

- "Harappan link". Frontline. 19 January 2008.

- "Excavation Bhirrana | ASI Nagpur". excnagasi.in. Retrieved 21 August 2020.

- "The ageless tale a potsherd from Bhirrana tells". The Hindu. 12 September 2007. Archived from the original on 17 September 2007.

- "Images of Excavation Site – Bhirrana, A Harappan town – Archaeological Survey of India". asi.nic.in. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 14 July 2007.

Further reading

- The Tribune, 2 January 2004

- Purātattva, The Bulletin of the Archaeological Society of India No. 34, 35 and 36;

- Man and Environment xxxi